| 343. The Foundation Course: Creative speech and Language

29 Sep 1921, Dornach Translated by Hanna von Maltitz Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| It's the objection that it does not interest the religious today whether there are two Jesus children. I can completely understand how, in the religious mood of today, little value is placed in such things. Now there is something else. |

| Imagination, drawn out of the world all, becomes the form of man, but what is drawn out of the world all needs to be understood according to its position in the world all. Every single human organ takes place in the verticalization. |

| I have always, when I deal with this alleged parable, said: there is a big difference whether a teacher said to himself: I am clever and the child is stupid, therefore I must create a parable for the child so that he can understand what I can understand with my mind.—Whoever speaks in this way has no experience of life, no experience of the imponderables which work in instructions. |

| 343. The Foundation Course: Creative speech and Language

29 Sep 1921, Dornach Translated by Hanna von Maltitz Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

[ 1 ] My dear friends! Up to now I've been introducing my lectures by indicating what the Anthroposophic path is like, implementing my lectures out of Anthroposophy in order to lead towards the initiation of the renewal of religious life, out of the wishes present in the souls of contemporaries. [ 2 ] Naturally first of all it is necessary to look more closely at what would be needed for the actual renewal of religious life. I would like to, in order to bring this into a clearer light, still today refer to the relationship, not of religion to Anthroposophy but the reverse, that of Anthroposophy to religion; but I have to say in advance, my dear friends, it is necessary, if we want to understand one another here, for a clear awareness of the seriousness of the relevant question in relation to its meaning in world history. If someone in a small circle sees some or other deficiency, finds this or that imperfection and is not able to perceive its relationship in our world's entire evolution, they will not quite rightly develop in their heart, or have a sense to develop, what is actually needed at present. [ 3 ] We live in a time where humanity has been deeply shaken and with all the means at its disposal to do something, with all these means humanity has actually failed to move forward. As a result I particularly want to be clear that I believe, even if it perhaps doesn't appear as pertinently—let me quite sincerely and honestly express my opinion on this matter—that I believe the rift between those who have lived for a longer time in pastoral work and those younger ones who stand before this need today, and only enter it today, is far greater. Even though it might not yet be felt so strongly, yet it is still there, and it will appear ever more clearly; I believe that for many the question between older and younger people, if I might express it this way, is to experience its formulation very differently. It seems to me that for the younger ones the formulation as we saw it yesterday, appears no longer to carry the same weight; it has already been dismissed. Let's be quite honest with ourselves, and clear, that there is a difference whether we can, in a sense defend a cause in which we are, or whether it takes strength to get into it. We don't want to have any illusions about that. Of course, when one is older one could say one has the same earnest interest as a youngster.—Yet, we need to take into account all possible subconscious impulses, and for this reason I ask you already, because we are dealing with things of a serious nature, to accept what I want to say today. [ 4 ] You see, Anthroposophy is quite at the start of its work, and anyone who uses Anthroposophy to develop some or other area, certainly has the experience that all he can still experience for himself in anthroposophical knowledge, the biggest difficulty arrives when he wants to share this with the world. This is just a fact, this is the biggest difficulty. Why? Because today we simply don't have the instrument of speech which is fully suited to concisely express what is seen through Anthroposophy. The Anthroposophist has the expectation that through Anthroposophy not merely such knowledge should come which live within the inner life, which they see as an inner observation, because it is unattainable for the human race in its entirety. For us this must be of foremost importance: What is possible in the human community?—and not: What can the individual demand?—Let us be clear, my dear friends, whoever is an Anthroposophist speaks out of reality, and in me speaking to him I don't feel as if I'm merely speaking in general, but when I speak to such a person it seems that either he is a priest or he should become someone who cares for the soul. Theoretically one can thus in the same manner shape one's endeavours in the most varied human areas. As soon as one enters into such a specialised field, one has to always state the most concrete of opinions which one can only take in. Please observe this. I'm making you aware that Anthroposophy certainly knows it stands at the start of its willing, a will which has to develop quite differently than the way in which it has already stepped in front of the world today. On the other hand, one can see that the world longs very, very strongly for what lies as a seed in Anthroposophy. [ 5 ] Something exists as a seed in Anthroposophy, which is rarely noticed today. This is the speech formation element itself. If you read Saint Martin's words, who was still a guardian of a religious belief katexochen in the 18th century—Matthias Claudius has translated the work of Saint Martin entitled Errors and Truth which should be republished—if you read Saint Martin, you find him speaking from a certain implicitness that humanity possessed an ancient speech which has been lost, and that one can't actually express in current differentiated languages what could be said about the supersensible worlds, and which should be expressed about the supersensible. So the Anthroposophist often has the feeling he would like to say something or other, but when he tries to formulate it, it leaves him speechless and doesn't come about. Yet Anthroposophy is creative speech. No one is able to meet something in such a way as Anthroposophy—what once was encountered in this way was in olden times and always occurred at the same time as religious formation—no one can encounter anything without a certain theological approach to final things in life like death, immortality, resurrection, judgement, without a certain anticipation of the future, therefore Anthroposophy must in her inward convictions look, at least for a short span of time, into the future and it must to some extent predict what must necessarily happen in the future and for the future of humanity. That is, that mankind is able to strip off all such connections with single individual languages which still exist today, and which more than anything have drawn nations into war and hardship. Ever again one must address the comparison of the Tower of Babylon construction and understand it today when one sees how the world is divided. Anthroposophy already has the power to sense something expressed between the differentiated spoken languages by looking from the original being of the sounds themselves; and Anthroposophy will, and not in the course of many centuries but in a relatively short time—even at is was initially suppressed, it soon rejuvenated—Anthroposophy will, through the most varied languages, not create a type of Yiddish language unit which is an abstraction from another, but it will out of itself creatively enter into the language and become reconciled with what is already in the human language. [ 6 ] Therefore, I want to tell you that Anthroposophy not only provides formal tasks of knowledge but that Anthroposophy has to face historical creative tasks. You can see what is in the hearts of people today who can create such things. I've been wanting for years to take the most important components in anthroposophical terminology, as paradoxical as this may appear, to try and give words formed out of sound. The time has not been ripe yet to accept this. But it is quite possible. [ 7 ] For this reason, I must call your attention to the real tasks of Anthroposophy. Why do I feel myself compelled to call your attention to it? Simply from the basis that as soon as mankind is ripe for the perception of the sound, for the word creative power itself, then everything which has up to now been in other spheres, in a more instinctive-animal way taking its course, must in future take place in the spiritual-human sphere. If humanity has come this far then it can sense the truth in a deed, sense what lives in the proclamation, in the message, in the Gospel, because the truth can't be sensed in the Gospel if one doesn't live in the creative power of a language. To really experience the Gospels, my dear friends, means to experience the details of the Gospels in every moment in which one lives, from having really recreated them within oneself. [ 8 ] Today's tendency is to only basically criticize the Gospels, one can't recreate them; but the possibility for their creation must be reworked. Where are the obstacles? The obstacles lie in already referring to the very first elements which were available for the creation of the Gospels. In fact, Gospel examination is placed on another foundation when the Gospel is thought about this way, than how it needs to happen from the character of the words. You see, under the objections which Dr Rittelmeyer mentioned, not as his but those of others, it is also one which is mentioned besides. It's the objection that it does not interest the religious today whether there are two Jesus children. I can completely understand how, in the religious mood of today, little value is placed in such things. Now there is something else. During the coming days we see, published in the Kommenden Tag-Verlag, how unbelievable the Gospel understanding is regarding the promotion of this "trivial matter"—it is however no small matter—how the power which created the Gospels is promoted by simply referring to a proof of what stands in the Gospels, regarding the two Jesus children. People don't understand the Gospels, they don't know what is written in them. However, the creative power of speech must be drawn out of further sources, and as a result, develop the heart and mind for these sources so that from the heart and mind the first of the four sections which I've given you in the description of the Mass can be given. You see, it doesn't mean the Mass is only being presented symbolically, but that the Mass symbolism becomes an expression for the totality of the pastoral process. If the totality of the pastoral work does not flow together into the Mass as its central focus, then the Mass has no meaning; the coming together of the pastoral ministry in the Mass or the modern symbolism that can be found—we will speak about this more—only then, in the full measure of the four main sections of the Mass, which I have mentioned, can it be fully experienced. [ 9 ] The reading of the Gospel to the congregation is only a part; the other part is expressed in the sermon. The sermon today is not what it should be, it can't be as it is intellectual because as a rule the preparation for the sermon is only intellectual and arising out of today's education, out of today's theology, can't be anything else. The sermon is only a real sermon when the power of creative speech ensouls the sermon, in other words when it doesn't only come out of its substance but speaks out of the substance of the genius of the language. This is something which must first be acquired. The genius of language is not needed for religiosity which is in one's heart, but one needs the genius of language for the religious process in the human community. Community building must be obligatory for the priest, as a result, elements must be looked for which are supportive of community building. Community building can never be intellectual, because it is precisely the element which creates the possibility of isolation. Intellectualism is just agreed upon by the individual as an individual human being and to the same degree, as a person falls back on his singularity, to that degree does he become intellectual. He can understandably save his intellectualism through faith because faith is a subjective thing of individuals, in the most imminent sense one calls it a thing of the individual. However, for the community we don't just need the subjective, but for the community we need super-sensory content. [ 10 ] Now, just think deeply enough about how it would be possible for you to effectively bring the mere power of faith to the community, without words. You wouldn't be able to do this, it is impossible. Likewise, you couldn't sustain the community by addressing it through mere intellectualism. Intellectual sermons will from the outset form the tendency to atomise the faithful community. Through an intellectual sermon the human being is thrown back onto himself; every single listener will be rejected by himself. This shakes up in him those forces which above all do not agree but are contradictory. This is a simple psychological fact. As soon as one looks deeper into the soul, every listener becomes at the same time a critic and an opponent. Indeed, my dear friends, regarding the secrets of the soul so little has been clarified today. All kinds of contradictions arise in objection to what the other person is saying when the only method of expression he uses is intellectual. [ 11 ] This is precisely the element which split people up today, because they are permeated thoroughly with mere intellectualism. You are therefore unable, through the sermon, to work against atomising, if you remain in intellectualism. Neither in the preparation of the sermon, nor in the delivery of the sermon must you, if you want to build community today, remain in intellectualism. Here is where one can become stuck through our present-day education and above all in the present theological education, because in many ways it has become quite intellectual. In the Catholic Church it has become purely intellectual, and all that which is not intellectual, which should be alive, is not given to individuals but has become the teaching material of the church and must be accepted as the teaching material of the church. A result of this is, because everything which the Catholic Church gives freely as intellectual, the priest is the most free individual one can imagine. The Catholic Church doesn't expect people to somehow submit to their intellect, inasmuch as it releases them from what is not referred to as the supernatural. All they demand is that people submit to the teaching material of the church. Regarding this I can cite an actual example. I once spoke to a theologian of a university, where at that time it paid general homage to liberal principles, not from the church but from liberal foundations. Of course, the theological faculty was purely for the Catholic priesthood. This person I spoke to had just been given a bad rebuke by Rome. I asked him: How is this actually possible that it is precisely you who received this rebuke, who is relatively pious in comparison to the teacher at the Innsbruck University—who I won't name—who teaches more freely and is watched patiently from Rome?—Well, you see, this man answered, he is actually a Jesuit and I'm a Cistercian. Rome is always sure that a man like him, who studies at the Innsbruck University never drops out, no matter how freely he uses the Word, but that the Word should always be in the service of the church. With us Cistercians Rome believes that we follow our intellect because we can't stand as deeply in our church life as the Jesuit who has had his retreat which has shown him a different way to the one we Cistercians take.—You see how Rome treats intellectualism psychologically. As a rule, Rome knows very clearly what it wants because Rome acts out through human psychology, even though we reject it. [ 12 ] Now, what is important is that above all, the sermon should not remain in intellectualism. All our languages are intellectual, we don't have the possibility at all, when we use common languages, to come away from the intellect. But we must do it. The next thing you come to, with which you need work as purely formative in the power of creative speech, is symbolism, but now formed in the right way, not by remaining within intellectualism but by really experiencing the symbols. To experience symbols indicates much more than one ordinarily means. [ 13 ] You see, as soon as the Anthroposophist comes to imaginative observation or penetrates the imaginative observation of someone else, he actually knows: The human being who stands in front of him is not the same person he had been before he had seen the light of Anthroposophy. You see, this person, who stands in front of us, is considered by current science to be a more highly developed animal; generally speaking. Everything which science offers to corroborate these views and generally justifies it is by saying a person has exactly as many bones and muscles as the higher animals, which is all true, but science comes to a dead end when one really presents the difference between people and animals. The differences between people and animals are not at all to be referred to through comparative anatomy, whether the whole human being or a single part of it, and an entire animal or part of an animal is similar, but to grasp what is human is to understand what results when human organs are situated vertically while the animal organs lie parallel with the surface of the earth. That one can also observe this in the animal kingdom as far as it proves the rule, is quite right, but that doesn't belong here, I must point out the limitations. Because the human being is organised according to the vertical plane with his spine, he relates in quite a different way to the cosmos than does the animal. The animal arranges itself in the currents circulating the earth, the human being arranges itself in currents which stream from the centre point of the earth in the direction of the radius. One needs to study the human being's situation in relation to space in order to understand him. When one has completed one's study of the human being's relationship to space, and make it alive once again, as regards to what it means that the human being is the image of God. The human being is not at all what comparative anatomy sees, he is no such reality as anatomy describes him to be, but he is, in as far as he is formed, a realization of an image (Bildwirklichkeit). He represents. He is sent out of higher worlds into conception and birth so that he represents what he brings from before his birth. Out of the divine substance we have our spiritual life before birth. This spiritual life dissolves through conception and birth and achieves a representation in the physical person on earth, an imagination. Imagination, drawn out of the world all, becomes the form of man, but what is drawn out of the world all needs to be understood according to its position in the world all. Every single human organ takes place in the verticalization. The human being is placed into the world by God. [ 14 ] This happens directly as an inner experience as the human being is grasped by the imagination. One can no longer intellectually say and believe that when I say the words "Man is the image of God" that we are only talking about a comparison. No, the truth is expressed; super-sensibly derived similarities from the Old and New Testaments can be found not as allegorical similarities, but as truths. We need to reach a stage when our words are again permeated by such experiences, that we learn to speak vividly in this way. In the measure to which we in a lively way enter into vivid characterisation, not through contriving something intellectually, we come to the possibility of the sermon, which should be an instruction. [ 15 ] I have often pointed out that when a teacher stands in front of a child and wants to teach him in a popular form about the immortality of the soul, he should do so through an image. He will need to refer to the insect pupa, how the butterfly flies out of it, and then from there go over to the human soul leaving the human body like a pupa shell; permeating this image with a super-sensible truth. I have always, when I deal with this alleged parable, said: there is a big difference whether a teacher said to himself: I am clever and the child is stupid, therefore I must create a parable for the child so that he can understand what I can understand with my mind.—Whoever speaks in this way has no experience of life, no experience of the imponderables which work in instructions. Because the convincing power with which the child grasps it, what I want to teach with this pupa parable, means very little if I think: I am clever and the child is stupid, I must create a parable for him which works.—What should be working firstly comes about within me, when I work with all the phases and power of belief in my parable. As an Anthroposophist I can create this parable by observing nature. Through my looking at the butterfly, how it curls out of the pupa, I am convinced through it that this is an image of the immortality of the soul, which only appears as a lower manifestation. I believe in my parable with my entire life. This facing of others in life is what can become a power of community building. Before intellectualism has not been overcome to allow people to live in images once again, before then it will be impossible that a real community building power can occur. [ 16 ] I have experienced the power of community building, but in an unjust field. I would like to tell you about that as well. Once I was impelled to study such things as to listen to an Easter sermon given by a famous Jesuit father. It was completely formulated according to Jesuit training. I want to give you a brief outline of this sermon. It dealt with the theme: How does the Christian face up to the assertion that the Pope would set the Easter proclamation according to dogma, it wouldn't be determined as God's creation but through human creation?—The Jesuit father didn't speak particularly deeply, but Jesuit schooled, he said: Yes my dear Christians, imagine a cannon, and on the cannon an operator or gunner, and the officer in command. Now imagine this quite clearly. What happens? The cannon is loaded, the gunner holds the fuse in his hand, the gunner pulls on the fuse when the command is sounded. You see, this is how it is with the Pope in Rome. He stands as the gunner beside the cannon, holds the fuse and from supernatural worlds the command comes. The Pope in Rome pulls on the fuse and thus gives the command of the Easter proclamation. It is a law from heaven, just like the command does not come from the gunner but from the officer. Yet, something deeper lies behind this, my dear Christians—the father says—something far deeper lies beneath it, when one now looks at the whole process of the Easter proclamation. Can one say the gunner who hears the command and pulls on the fuse, is the inventor of the powder? No. Just as little can one say that the Catholic Pope has instituted the Easter proclamation. The faithful are drawn by a feeling into the congregation through the use of this image, this representation but obviously in an unjust a field as possible. [ 17 ] The symbol can be a way for the human heart to actually find the supersensible, but we, like I've indicated with the comparison to the insect pupa, need to learn to live within the symbol; to be able to faithfully take the symbol itself from the outside world. I clearly understand when someone wants to appeal to mere faith as opposed to knowledge. I take this so seriously, that this faith must also manifest and be active in the living of oneself in the face of outer nature, so that the entire outer nature becomes a symbolum in the true sense of the word, an experienced symbolum. My dear friends, before the human being again realizes that in the light not mere comparisons of wisdom live and weave, but that in the light wisdom really live and weave ... (gap in notes) ... light penetrates into our eyes, what is light is then no longer light—with "light" one originally referred to everything which lay at the foundation of human beings as their inner wisdom—because by the light's penetration it becomes inwardly changed, transubstantiated, and each thought which rises within, my dear friends, is changed light in reality, not in a parable. [ 18 ] Don't be surprised therefore that the one who has got to know through appropriate exercises that to some extent outer phenomena describe inner human thoughts, by describing them in light imagery. Do not be surprised because that corresponds to reality. [ 19 ] Things were far more concretely taken in the ancient knowledge of mankind than one usually thinks. You must also become knowledgeable with the fact that the power which then still lived in the Gospels, have in the last centuries also got lost, like the original revelation of man has really been lost as has the original language been lost. Now I want to pose the question: do we grasp the Gospels today? We only grasp them when we can really live within them and presently, out of our intellectualized time epoch, we can't experience them thus. I know very well about the opposition expressed against my interpretations presented in my various Gospel lectures, from some or other side, and I'm quite familiar that these are my initial attempts, that they need to become more complete; but attempts to enliven the Gospels, these they are indeed. [ 20 ] I would like to refer back to times, my dear friends, when there were individuals who we today, when you imagine the world order at that time there also existed, those we call chemists. Alchemists they were called in the 12th and 13th centuries, and they were active with the material world which we usually can observe in chemists. What do we do today in order to create a real chemist? Today our preparations for the creation of a chemist is his intellectual conceptions of how matter is analysed and synthesized, how he works with a retort, with a heating apparatus, with electricity and so on. This was not enough, if I may express it this way, for a real chemist, up to the 13th and 14th centuries—perhaps not to take it word for word—but then the chemist had opened the Bible in front of him and was permeated in a way by what he did, in what he did, by what flowed out of the Bible in a corresponding force. Current humanity will obviously regard this as a paradox. For humanity, only a few centuries ago, this seemed obvious. The awareness which the chemist had at that time, in other words the alchemist, in the accomplishment of his actions, was only slightly different to standing at the altar and reading the mass. Only slightly different, because the reading of the mass already was the supreme alchemical act. We will speak about this more precisely in future. Should one not be creating knowledge out of these facts that the Gospels have lost their actual power? What have we done in the 19th century? We have analysed the Gospels of Mark, John, Luke and Matthew, we have treated them philologically, we have concluded that John's Gospel can be nothing, but a hymn and that one can hardly believe it corresponds to reality. We have compared the various synoptists with one another and we have reached the stage which ties to the famous blacksmith where distillation takes place: what is said iniquitously about the Christ is the truth because you won't find that with mere hymns of praise.—This is the last consequence of this path. On this path nothing else can happen than what has already happened: the destruction of the Gospels will inevitably arise in this way. While we are still so much into discussing the division between knowledge and faith, it will not be sustained if science destroys the Gospels. One must certainly stand within reality and need to understand how to live out of reality, and therefore it is important that the pastor must come to a living meaning of the perceptible representations, the perceptible-in-image representations. The living image must enter into the sermon. That it should be an acceptable, a good image, it obviously must have a purity of mood, of which we will speak about. It's all in the image; the image is what we need to find. [ 21 ] Now my dear friends, for the discovery of the image you will be most successful with the help of Anthroposophy. Anthroposophy is mocked because of its pictoriality. If you read how the intellectuals—if I may use the word—apply their opposition to my depiction of evolution, you will soon see how easy it is from the intellectual point of view to mock the images which I have to use in my depiction of the Old Saturn-, Sun- and Moon existence. I have to use images otherwise things would fall out of my hands, because only though images I can grasp the reality which has to be searched for. I would like to say, Anthroposophy has in each of its parts definitely a search for images and is for this reason the helper for those who use images. Here lies the real field, where the pastor can firstly benefit much from Anthroposophy. Not as if he has to undertake to believe in Anthroposophy, not as if he has to say: Well now, let's study anthroposophical images and books, then we can use them.—This is no argument. It needs to come, so to speak, to the opposite of what had to develop in philosophy, into an age that lived contrary to Anthroposophy. [ 22 ] To this I would like to say the following. Philosophers today who are students of a content or a system, or of the belief that a system needs to be established, such philosophers are antiquated; such philosophers have remained behind. Such system-philosophies are no longer possible in the intellectual time epoch. When Hegel presented his purely intellectualism in his last thoughts of the human conception and placed this in his overall system, he had created what I would like to call the corpse of philosophy. Exactly like science studies the human corpse, so can one in Hegel's philosophy in a corpse-like way study what is philosophy—as only that, it is very good. That is why the Hegelian philosophy is so great, because nothing disturbs the flow of intellectualism to really study it. The amazing thing I admire for example, is to develop something pure which is purely intellectualistic. However, after Hegel there can no longer be such endeavours which take thought content to create a philosophic system. That is why people create such awful somersaults. Yes, one can't think of worse somersaults than the philosophy of Hans Vaihinger, called the "As-if" (Als Ob). As if one can have something like a philosophy called: "As if." It is created from experience in the mind, this philosophy of "As if." It is not even a philosophy out of what humanity was, but the last imaginative remnants in humanity, which are translated into thoughts. What philosophers are obliged to study today should be a practice in pure thinking. To study philosophy today is meditative thinking and should not be practiced in any other way. I believe that if one looks at these things in an unprejudiced way, one will soon see that what I have offered in my Riddles of Philosophy as the development of philosophy, that it constantly proposes one can work through the most diverse philosophic systems as an exercise in thinking. One can learn unbelievably much out of the latest systems, in the Hartmann system and the American system linked to the name of James. One can learn unbelievably much in as far as one lets it work on one to such a degree that one asks: How is thinking trained; what does one gain from thought training?—Please forgive the hard words. Nietzsche had already made an effort to introduce such thought training in philosophy. [ 23 ] This will draw your attention, regarding philosophy, to today's need that man must direct thought content into direct living content, not by positioning oneself as a subject against the truth from outside, but in such a way that truth becomes an experience. Only one who has understood current philosophising in this way will actually be able to understand the contrary; for readers of anthroposophical writing and hearing anthroposophical lectures it does not mean things are to be taken up as dogma. That would be the most incorrect attitude to have. Just think, what is given in Anthroposophy has actually been brought down out of the supersensible, it may have been awkwardly put into words, but when one allows oneself to reach deeper, it will be as if the true philosopher in his thoughts reaches deeper into other philosophies. He would not take anything from other systems, he takes the blame. The image capability for the pictorial, for the sake of clarity, is the first step to educate students in Anthroposophy. When words are encountered which have flowed out of imaginative thinking, when such thoughts are taken up, then it is necessary, in order to really understand them, to raise the pictorial power out of them from soul foundations. Above all, that's what we can do to help Anthroposophy. [ 24 ] One therefore appeals less by saying: Well, I must first for my own sake become clairvoyant, then I can make some decisions about Anthroposophy.—One appeals in such a way that one firstly, quite indifferently, get to know the content of truth in Anthroposophy; one simply takes the sum of all the images which shows how one or other soul paints it. That is at least a fact which they paint for themselves. One takes this and first allows the inherent truth to remain undecided, but then one tries to find within it, how the person speaks who has such supersensible images, and one will see that this is the best way to enter in to seeing for oneself. With many people who encounter Anthroposophy today it is as if they set the wagon straight but then incorrectly spans the horse to it. (A stenographer's note indicates that a horse was drawn on the blackboard with the wagon positioned in one way, while the horse is drawn with its head towards the wagon and its tail pointing to the road ahead. The original drawing was not preserved.) There is no need for this; that one must first learn to be a seer. It could, in fact happen due to a certain arrogance and then the thing as a whole is passed by. If one has the humility to want to experience the seeing adequately, then one can come to the perception without the fear of receiving a suggestion. The fear of receiving a suggestion can only be had by philosophers alien to reality; which we have for instance with Wund, the latecomer of system philosophers who of course from his point of view, argued: Yes, how would I know if what I've first perceived of the supersensible world and look at it, that it was not suggested to me?—One should reply the Wund: How do you actually know the different between a piece of iron with a temperature of 100 degrees or higher which you can only imagine, or another one which is lying in front of you? You can discuss this for a long time but by looking at it you will never discover whether the iron is really lying in front of you or whether it is suggested; but when you grab hold of it and look at your fingers, then you will find the difference—through life. There is no other criterion. [ 25 ] It is however an unmistakable criterion, if one places oneself into life in such a way to come into Anthroposophy. One may however not take on the point of view that one knows everything already. In my life I have found that people learn the least when they believe they already know what they should learn. [ 26 ] It is for instance only possible to be a real teacher when you are a teacher of attitude. How often is it said to teachers in the Waldorf schools—and you have understood, in the course of years it has happened that teaching is characterised by this attitude; it is clearly noticeable—how often is it not said: When one stands in front of a child, then it is best to say to oneself that there is far more wisdom in the child than in oneself, much, much more because it had just arrived from the spiritual world and brings much more wisdom with it. One can learn an unbelievable amount from children. From nothing in the world does one basically learn so much in an outer physical way, as when one wants to learn from a child. The child is the teacher, and the Waldorf teacher knows how little it is true that with teaching, one is the teacher and the child the scholar. One is actually—but this one keeps as an inner mystery for oneself—more of a scholar than a teacher and the child is more teacher than scholar. It seems like a paradox, but it is so. [ 27 ] You see, Anthroposophy directs us to new knowledge about the world, in many special areas in life, so it is worthy of questions which are thought through ... (Gap in notes). Yes, Anthroposophy appears consistently in this mood, with this attitude. Anthroposophy just can't appear without a religious character as part of it. This must also be stressed about Anthroposophy: Anthroposophy does not strive to appear as creating religious instruction, as building a sect; it strives to give humanity a content to their inner experiences which lets them strive to what comes quite out of themselves, which is expressed with religious characteristics. Anthroposophy is not a religion but what it gives is something which works religiously. [ 28 ] Very recently I had to speak to a person whose earlier life situation was not quite over confident, but of a joyful nature, and who descended into a deep depression, a depression which had various, even organic, causes. This man is an Anthroposophist, he wanted to speak about his mood to me. I pointed out that a mood comes out of the totality of a person, and one gets a mood out of what one absorbs from the world in that one confronts the world as a human being. Anthroposophy itself is a person (Mensch). If it wasn't a person, it wouldn't transform us. Out of us it makes us into someone different. It is a person itself, I say it in the greatest earnestness. Anthroposophy is not a teaching, Anthroposophy has an element of being, it is a person. Only when a person is quite permeated by it and Anthroposophy is like a person who thinks, but also feels, senses and has emotions of will, when Anthroposophy thinks, feels and wills in us, when it is really like a complete person, then one can grasp it, then you have it. Anthroposophy acts like a being and it enters present culture and civilization like a kind of being. One experiences this entering as by a kind of being. With this at the same time one can say: Religion—spoken from the anthroposophic stand point—religion is a relationship of human beings to God. However, Anthroposophy is a person, and because it is a person, it has a relationship with God; and like a person has a relationship to God, so it has a relationship to God. Thus, it has the direct characteristic of the religious in itself. [ 29 ] I will now summarise this finally in some abstract sentences which do however have life in them. What I have said before and what I say now are interrelated and I don't say it without purpose, my dear friends. The first one which is experienced in this way is that one leans to recognise how godly wisdom acts in the child, where it is creative, where it not only comes to revelation in a brain, but where it still shapes the brain. Yes, "if you would not become like little children, you shall never enter into the kingdom of the heavens ..." That is the way to penetrate into what you notice in the deep humility of the child, that which lies before becoming a child, that which even Goethe experienced so lovingly, that he used the word "growing young" (Jungwerden) for entering into the world, like one can say "growing old" (Altwerden). Growing young means stepping out of the spiritual state, into earthly existence. One goes in a certain sense really through childhood and back to such a state where one still had a direct relationship with the divine. The old Biblical questions become quite real: Can one return into the mother's body, to experience a rebirth?—In spirit one can do this. However, in the old way where the Bible lay in front of the alchemists, and the new way which prepares us for handling the world, lies an abyss. The abyss must be bridged over. We will however not find the old ways, because we need to find a new way. I have often spoken out among Anthroposophists what we might find when we are willing to do some kind of manipulation of nature. The "Encheiresis naturae" (an intervention by the hand of nature—Google) we must accomplish again, but we mustn't say "don't cut your nose to spite your face"; we must be able to take it in the greatest earnest then we will have an ideal , in any case only as an ideal, but an ideal which becomes reality. The laboratory workbench will in a certain sense become an altar, and the outer action in the world will become a service of divine worship and all of life be drenched by the light of acts of worship. [ 30 ] Now for the second thing: Anthroposophy as speech formation. Anthroposophy needs to strive to have such a grasp in the world, that I can apply the reality which I've presented today as an apparent contradictory image: the laboratory bench of the chemist, the physics-chemistry of clinical work must in human experience take on the form of an altar. Work on humanity, also the purely technical work—must be able to become a service of divine worship. That one will only be able to find when one has the good will to cross over the abyss which separates our world from the other side where the Gospels lay before the alchemists. |

| 343. The Foundation Course: Speech Formation

29 Sep 1921, Dornach Translated by Hanna von Maltitz Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Regarding the power of speech formation: we actually have no direct understanding of sound anymore today; we basically have no more understanding for words, so our words remain signs. |

| [ 15 ] Such things must be acquired again by living within Christianity and what Christianity has derived from the ritual practice of the Old Testament. There is no shortcut to understanding the Gospels; a lively participation in the ancient Christian times is necessary for Gospel understanding. |

| This question can hardly be answered briefly because it relates deeply to the abyss which exists between today's evangelist-protestant religious understanding and all nuances of Catholic understanding. It is important that in the moment when these things are spoken about, one must try to acquire a real understanding beyond the rational or rationalistic and beyond the intellectualistic. |

| 343. The Foundation Course: Speech Formation

29 Sep 1921, Dornach Translated by Hanna von Maltitz Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

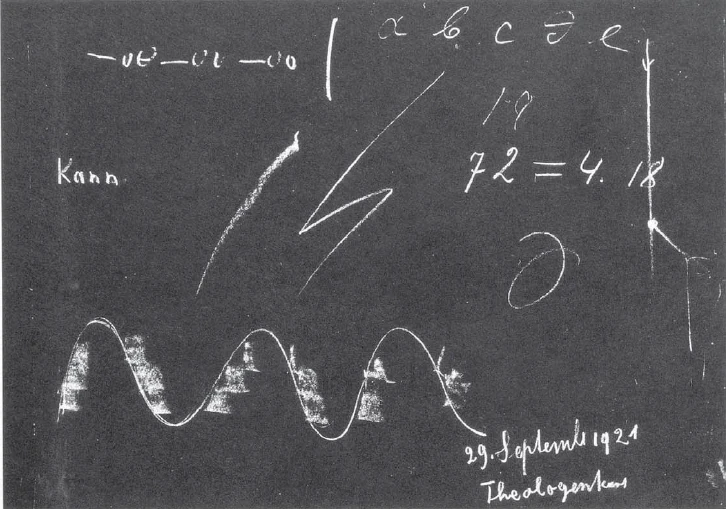

Emil Bock opened the discussion hour and formulated the following questions:

[ 1 ] Rudolf Steiner: With regards to the first question: You would already have seen, my dear friends, that out of what I said this morning, that in the illustration, the soul contents related to the supersensible and also what leads to the power of formative speech, must be searched for. Regarding the power of speech formation: we actually have no direct understanding of sound anymore today; we basically have no more understanding for words, so our words remain signs. Naturally our starting point needs to be out of the spiritual milieu of our time. Man must be responsible for these intimate things out of what currently is available. Precisely such a question brings us naturally into the area of the purely technical. First of all one has to make the understanding for the sound active again, within oneself. One doesn't easily manage the free use of speech when one isn't able to allow the sound as such, to stir within oneself. I would like to continue in such a way that I first draw your attention to certain examples. [ 2 ] You see, when we say "head" (Kopf) in German, we hardly have anything else in mind than the total perception of what reaches us through the ear, which indicates the head. When we say "foot" (Fuss) it is hardly any different to what we experience in the tonality and sound content in relation to some foot. Now we only need, for instance, to refer to the Romance languages where head is testa, tête, foot is pedum, pied, and we get the feeling at the same time that the term is taken from something completely different. When we say the word Kopf in German, the term has come out of the form, from looking at the form. We are not aware of this any longer, yet it is so. When we say Fuss, it is taken from walking where furrows are drawn in the ground. Thus, it has come into existence out of a certain soul content and coined in a word. When we take a word formation like, let's say, "testament" and all other word formations which refer in Romance language terms to head, testa, then we will feel that the term Kopf in the Romantic languages originate through the substantiation and thus not out of the form, but through the human soul with the help of the head, and particularly activating the mouth organs. Pied didn't originate from walking or drawing furrows but from standing, pressing down while standing. Today we no longer question the motives which have come out of the soul and into speech formation. We can only discover what can be called, in the real sense, a feeling for the language when we follow the route of making language far more representational than it is currently, abstraction at most. When someone uses a Latin expression in terminology, some Latin expressions are even more representational, but some people use them to denote even more. For example, today one can hardly find the connection between "substance" and "subsist" while the concept of "subsist" has basically been lost. Someone who still has the original feeling for substance and subsistence would say of the Father-God, not that He "exists" but that he "subsists." [ 3 ] Researching language in this way and in another way which I want to mention right now, in order to develop a lively feeling for language again, leads then to something I would like to call a linguistic conscience (Sprachgewissen). We need a linguistic conscience. We speak really so directly these days because as human beings we act more as automatons towards language than we do as living beings. Until we are capable of connecting language in a living way to ourselves, like our skin is connected to us, we will not come to the right symbolization. The skin experiences pain when it is pricked. Language even tolerates being maltreated. One must develop a feeling regarding language that it can be maltreated because it is a closed organism, just like our skin. We can gain much in this area, when we have a lively experience in some or other dialect. Consider how often we have performed the Christmas Plays, and in these plays there is a sentence spoken by one or more of the innkeepers. When Joseph and Mary come to Bethlehem in search of lodging, they are refused by three innkeepers. Each one of the three innkeepers says: Ich als a wirt von meiner gstalt, hab in mein haus und ligament gwalt.—Just imagine what this means to a person today. He could hear: "I as a host of my stature ..."—and think that what the host is saying means he is an attractive man, or something like that, or a strong man who has stature within his hostel, in his house. This is certainly not meant. If we want to translate that into High German we'll have to say: "I as a host, who is placed in such a way as to have abundant comfort, I am not dependent on such poor people finding lodgings within, with me." This means: "I as a host in my social position, in my disposition." This shows them it is necessary not only to listen to him—words one often enough hears in speech—but to enter into the spirit of the language. We say Blitz" (lightening) in High German. In Styria a certain form of lightening is called 'heaven's lashers' (Himmlatzer). In the word "Blitz" there is quite another meaning than in the word Himmlatzer. [ 4 ] So we start becoming aware of different things when we approach the sense of speech. You see, such an acquisition of the sense of language sometimes leads to something extraordinarily important. Goethe once uttered a sentence, when already in his late life, to the Chancellor von Müller, a statement which has often been quoted and is often used, to understand the entire way in which Faust, written by Goethe, originated. Goethe said that for him the conception of Faust had for 60 years been clear "from the beginning" (von vornherein); the other parts less extensively. Now commentary upon commentary have been written and this sentence was nearly always recalled, because it is psychologically extraordinarily important, and the commentators have it always understood like this: Goethe had a plan from the beginning for his Faust and in the 60 years of his life—since he was twenty or about eighteen—he used this plan, he had "from the start," to work from. In Weimar I met August Fresenius who bemoaned the fact that it was a great misfortune, if I could use such an expression, which had entered into the entire Goethe research, and at the time I had urged an unusually thoughtful and slow philologist to publish this thing as soon as possible in order that it doesn't continue, otherwise one would have a few dozen more such Goethe commentaries. It is important to note that Goethe used the expression "from the start" in no other way than in a descriptive way, not in the sense of a priori but "from the beginning" in a very descriptive manner so that in the strictest sense one could refer to Goethe not having an overall plan, but that "at the beginning" he only wrote down the first pages (i.e. to begin with) and of the further sections, only single sentences. There can be no argument of an overall plan. It very much depends on how one really experiences words. Many people have, when they hear the word vornherein totally have no conscience that it has a vorn (in front) and a herein (in) and that one sees something spiritual when one pronounces it. This simple dismissal of a word without contemplation is something upon which a tremendous amount depends, if one wants to attain a symbolic manner of speech. Precisely about this direction there would be extraordinarily much to say. [ 5 ] You see, we have the remarkable appearance of the Fritz Mauthner speaking technique where all knowledge and all wisdom is questioned, because all knowledge and wisdom is expressed though speech, and so Fritz Mauthner finds nothing expressed in speech because it does not point to some or other reality. [ 6 ] How harsh my little publication "The spiritual guidance of man and of mankind" has been judged in which I mention that in earlier times, all vowel formation expressed people's inner experiences, and all consonant unfolding comes from outer observed or seen events. All that man perceives is expressed in consonants, while vowels are formed by inner experiences, feelings, emotions and so on. With this is connected the peculiar manner in which the consonants are written differently to the vowels in Hebrew. This is also connected to areas where more primitive people used to dwell, where they have not strongly developed their inner life, so predominantly consonant languages occur, not languages based on vowels. This extends very far, this kind of in-consonant-action of language. Only think what African languages have from consonants to click sounds. [ 7 ] So you see, in this way we gain an understanding for what sounds within language. One would be brought beyond the mere sign, which the word is today. Only with today's feeling for language which Fritz Mauthner believes in, can you believe that all knowledge actually depends on language and that language has no connection to some or other reality. A great deal can be accomplished when one enters into one's mother tongue and try to go back into the vernacular. In the vernacular one finds much, very much if you really behave like a human being, that is, respond to what you feel connected to the language. In the vernacular one has the rich opportunity to feel in speech and experience in sound, but also the tendency towards the descriptive, and you have to push it so far that you really, one could say, get into a kind of state of renunciation in regard to expressions that are supposed to phrase something completely separate from human experiences. Something which thoroughly ruins our sense of language is physics, and in physics, as it is today, it only aspires to study objective processes and refrains from all subjective experience, there it should no longer be spoken at all. According to physics, when one body presses (stoßen) against another, for example in the theory of elasticity, then you are anthropomorphising, because the experience of pressure as soon as you sense sound, means you're only affected by the same kind of pressure as the pressure your own hand makes. Above all, one gets the feeling with the S-sound that nothing other can be described as something like this (a waved line is drawn on the blackboard). The word Stoß" (push/impacts—ß is the symbol for ss—translator) has two s's, at the end and beginning; it gives the entire word its colouring; so when the word Stoß or stoßen (to push/thrust) is pronounced one actually can feel how, when your ether body would move, it would not only move but be shoved forwards and continuously be kept up.  [ 8 ] Thus, there are already methods through which one comes to the power of speech formation, which is then no longer far from symbolizing, for the symbolum must be hacked out of the way so that one experiences language as a living organism, because much is to be experienced within language. Someone recently told me that there are certain things in language which only need to be pronounced and one is surprised at how they reveal themselves as self-evident. The Greeks recited in hexameter. Why? Well, hexameter is an experience. A person produces speech, as I've already said, in his breathing. However, breathing is closely connected to other elements of rhythm in the human being; with the pulse, with blood circulation. On average, obviously not precisely, we have 18 breaths and 72 heat beats; 72 equals 4 times 18. Four times 18 heart beats gives a rhythm, a collective inner beat. In a time when man sensed in a more primordial and more elementary way according to what was taking place within him, man experienced, when he could, in uttering the relationship of the heart beat to the breathing, bring the totality of himself into expression. This relationship, not precisely according to time, this relationship can be brought to bear; you only have to add the turning point as the fourth foot (reference plate 3 ... not available In German text) then you have a Greek hexameter half-line, in the ration of 4 to 1 as a pulse beat to breathing rhythm. The hexameter was born out of the human structure, and other measures of verse were all born out of the rhythmic system of the human being. You can already feel, when you treat language artistically, how, in the process of treating human speech in an artistic way, language is alive. This makes it possible to acquire a far more inner relationship to language, yet also far more objectivity. The most varied chauvinistic feelings in relation to language stops, because the configurations of different languages stop, and one acquires an ear for the general sound. There are such things which are found on the way to gaining the power of creative speech. It does finally lead to listening to oneself when one speaks. In a certain way it's actually difficult but it can be supported. For various reasons it seems to me that for those who are affected by it, it is also necessary not to treat the Scripture in the way many people treat it today. You will soon see why I say these things. [ 9 ] In relation to writing, there are two kinds of people. The majority learn to write as if it's a habit of staking out words. People are used to move their hands in a certain way and write like this: in the majority. The writing lesson is very often given in such a way that one just comes to it. The minority actually don't write in the sense of reality, but they draw (a word is written on the blackboard: Kann [meaning can; be able to]). They look at the signs of the letters simultaneously as being written, and as an artistic treatment of writing, it is far more an intimate involvement. I have met people who have been formally trained to write. For instance, once there was a writing method which consisted in people being trained to make circles and curves, to turn them and thus acquire a feeling of connecting them and so form letters out of them. Only in this way, out of these curves, could the letters come about. With a large number of them I have seen that they, before they start writing, make movements in the air with their pen. This is what brings writing into the unconsciousness of the body. However, our language comes out of the totality of the human being and when one spoils oneself by writing you also spoil yourself for the language. Precisely the one who is dependent on handling the language needs to get used to the meditation that writing should not be allowed to just flow out of his hand, but he should look at it, really look at what he is writing, when he writes. [ 10 ] My dear friends, this is something which is extraordinarily important in our current culture, because we are on our way to dehumanizing ourselves. I have already received a large number of letters which have not been written with a pen but with the typewriter. Now you can imagine the difference between a letter written with a typewriter or written with a pen. I'm not campaigning against the typewriter, I consider it as an obvious necessity in civilization, but we do also need the counter pole. By us dehumanizing ourselves in this way, by us changing our relationship towards the outer world in an absolute mechanistic and dead manner, we need in turn to take up strong vital forces again. Today we need far greater vital forces than in the time in which man knew nothing yet about the typewriter. [ 11 ] Therefore, for someone who handles words, he must also acquire an understanding for the continuous observation, while he is writing, that what he is writing pleases him, that he gets the impression that something hasn't just flowed out of a subject but that, by looking simultaneously at it, this thing lives as a totality in him. Mostly, the thing that is needed for the development of some capability is not arrived at in a direct but in an indirect way. I must explain this route because I have been asked how one establishes the power for speech formation. This is the way, as I have mentioned, which comes first of all. As an aside I stress that language originates in the totality of mankind, and the more mankind still senses the language, so much more will there be movement in his speech. It is extraordinary, how for instance in England, where the process of withdrawal of a connection with the surroundings is most advanced, it is regarded as a good custom to speak with their hands in their trouser pockets, held firmly inside so they don't enter the danger of movement. I have seen many English people talk in this way. Since then I've never had my pockets made in front again, but always at the back, for I have developed such disgust from this quite inhuman non-participation in what is being said. It is simply a materialistic criticism that speech only comes from the head; it originates out of the entire human being, above all from the arms, and we are—I say it here in one sentence which is obviously restricted—we are on this basis no ape or animal which needs its hands to climb or hold on to something, but we have them as free because with these free hands and arms we handle speech. In grasping with our arms, creating with our fingers, we express something we need in order to model language. So it has a certain justification to return mankind to its connection with language, bringing the whole person into it, to train Eurythmy properly, which really exists in drawing out of the human organism what is not fulfilled in the human body, but is however fulfilled in the ether body, when we speak. The entire human being is in movement and we are simply transposing though the eurhythmic movements, the etheric body on to the physical body. That is the principle. It is really the eurythmization of something like a necessity which needs to be regularly brought out of the human being, like the spoken language itself. It must stand as a kind of opposite pole against all which rises in the present and alienate people towards the outer world, allowing no relationship to be possible between people and the outer world any more. The eurythmization enables people in any case to return to being present in the language and is on this basis, as I've often suggested, even an art. Well, if you take into account the things I've just proposed, then you arrive at the now commonplace speech technique basically under the scheme of pedantry. The great importance given to teaching through recitation and that kind of thing, only supports the element of a materialistic world view. You see, just as one would in a school for sculpture or a school of painting not really get instructions of the hand movements but corrects them by life forces coming into them, so speech techniques must not be pedantically taught with all kinds of nose-, chest- and stomach resonances. These things may only be developed though living speech. When a person speaks, he might at most be made aware of one or the other element. In this respect extraordinary atrocities are being committed today and the various vocal and language schools can actually be disgusting, because it shows how little lives within the human being. The formation of speech happens when those things are considered which I mentioned. Now if the question needs to be answered even more precisely, I ask you to please call my attention to it. [ 12 ] Now there is a question about new commentary regarding the Bible, in fact, how one can arrive at a new Bible text. [ 13 ] You see, the thing is like this, one will first have to penetrate into an understanding of the Bible. Much needs to precede this. If you take everything which I have said about language, and then consider that the Bible text has originated out of quite another kind of experience of language than we have today, and also as it was experienced centuries before in Luther's time, you can hardly hope to somehow discover an understanding of the Bible through some small outer adjustment. To understand the Bible, a real penetration of Christianity is needed above all, and actually this can only emerge from a Bible text as something similar for us as the Gospels had once appeared for the first Christians. In the time of the first Christians one certainly had the feeling of sound and some of what can be experienced in the words in the beginning of St John's Gospel which was of course experienced quite differently in the first Christian centuries as one would be able to do today. "In the primal beginnings was the Word"—you see, today there doesn't seem to be much more than a sign in this line, I'd say. We come closer to an understanding when we substitute "Word," which is very obscure and abstract, with "Verb" and also really develop our sense of the verb as opposed to the noun. In the ancient beginnings it was a verb and not the noun. I would like to say something about this abstraction. The verb is quite rightly related to time, to activity, and it is absurd to think of including a noun in the area which has been described as in "the primal beginning." It has sense to insert a verb, a word related to activity. What lies within the sentence regarding the primal origins is however not an activity brought about by human gestures or actions, because it is the activity which streams out of the verb, the active word. We are not transported back into the ancient mists of the nebular hypothesis by the Kant-Laplace theory, but we will be led back to the sound and loud prehistoric power. This returning into a prehistoric power is something which was experienced powerfully in the first Christian centuries, and it was also strongly felt that it deals with a verb, because it is an absurdity to say: In the prehistoric times there was a noun.—We call it "Word" which can be any part of speech. Of course, it can't be so in the case of St John's Gospel. [ 14 ] In even further times in the past, things were even more different. They were so that for certain beings, for certain perceptions of beings one had the feeling that they should be treated with holy reserve, one couldn't just put them in your mouth and say them. For this reason, a different way had to be found regarding expression, and this detour I can express by saying something like the following. Think about a group of children living with their parents somewhere in an isolated house. Every couple of weeks the uncle comes, but the children don't say the uncle comes, but the "man" comes. They mean it is the uncle, but they generalise and say it is "the man." The father is not the "man"; they know him too well to call him "man." In this way earlier religious use of language hid some things which they didn't want to express outwardly because one had the inner reaction of profanity, and so it was stated as a generalization, like also in the first line of St John's Gospel, "in the beginning was the Word." However, one doesn't mean the word which actually stands there but one calls it something which has been picked out, a singular "Word." It was after all something extraordinary, this "Word." There are as many words as there are men, but children said, "the man," and so one didn't say what was meant in St John's Gospel, but instead one said, "the Word." The word in this case was Jahveh, so that St John's Gospel would say: "In the primal beginnings was Jahveh," so one doesn't say "God," but "the Word." [ 15 ] Such things must be acquired again by living within Christianity and what Christianity has derived from the ritual practice of the Old Testament. There is no shortcut to understanding the Gospels; a lively participation in the ancient Christian times is necessary for Gospel understanding. Basically, this is what has again become enlivened through Anthroposophy, while such things have in fact only risen out of Anthroposophic research. We then have the following: In the primordial times was he word—in primordial time was Jahveh—and the word was with God—and Jahveh was with God. In the third line: And Jahveh was one of the Elohim.—This is actually the origin, the start of the St John Gospel which refers to the multiplicity of the Elohim, and Jahveh as one of them—in fact there were seven—as lifted out of the row of the Elohim. Further to this lies the basis of the relationship between Christ and Jahveh. Take sunlight—moonlight is the same, it is also sunlight but only reflected by the moon—it doesn't come from some ancient being, it is a reflection. In primordial Christianity an understanding existed for the Christ-word, where Christ refers to his own being by saying: "Before Abraham was, I am" and many others. There certainly was an understanding for the following: Just as the sunlight streams out of itself and the moon reflects it back, so the Christ-being who only appeared later, streamed out in the Jahveh being. We have a fulfilment in the Jahveh-being preceding the Christ-being in time. Through this St John's Gospel becomes deepened through feeling from the first line to the line which says: "And the Word became flesh and lived among us." Even today we don't believe a childlike understanding suffices for the words of the Bible, when we research the Bible by translating it out of an ancient language until we penetrate what lies in the words. Of course, one can say, only through long, very long spiritual scientific studies can one approach the Bible text. That finally, is also my conviction. [ 16 ] Basically, the Bible no longer exists; we have a derivative which we have put together more and more from our abstract language. We need a new starting point in order to try and find what really, in an enlivened way, is in the Bible. For this I have suggested an approach which I will speak about tomorrow, in the interpretation of Mathew 13 and Mark 13. You will have to state in any case that even commenting on the Bible makes it necessary to deal with the Bible impartially. If it is stated that something is mentioned which had only taken place in the year 70, therefore the relevant place could not have been mentioned before other than what had happened after this event, this could be said only if it is announced at the beginning of the Bible explanation that the Bible will be explained completely from a materialistic point of view; then it may be done like this. The Bible itself does not follow the idea that it should be explained materialistically. The Bible itself makes it necessary that the foreseeing of coming events is first and foremost ascribed to Christ Jesus himself, and also ascribed to the apostles. Thus, as I've said, this outlook is what I want to enter into tomorrow on the basis of Mathew 13 and Mark 13, by giving a little interpretation as it has been asked for. [ 17 ] Another question asks about the reality behind the apostolic succession and the priest ordination. This question can hardly be answered briefly because it relates deeply to the abyss which exists between today's evangelist-protestant religious understanding and all nuances of Catholic understanding. It is important that in the moment when these things are spoken about, one must try to acquire a real understanding beyond the rational or rationalistic and beyond the intellectualistic. This is acquired even by those who have little right to live in the sense of such an understanding. In the past I have become acquainted with a large number of outstanding theosophical luminaries, Leadbeater also among them, about whom you would have heard, and some other people, who worked in the Theosophical Society. I have recently had the opportunity—otherwise I would not have worried about it again—to experience, that some of these people are Catholic bishops; it struck me as extraordinary that a part of them were Catholic priests. Leadbeater in any case had, after various things became known about him, not exactly the qualification to become a Catholic bishop. Still this interested me about how people become Catholic priests. One thing is observed with utmost severity, which is the succession. In order for me to see which people have the right to be Catholic bishops, I was given a document which revealed that in a certain year a Catholic bishop left the Catholic church, but one who was ordained, and he then ordained others—right up to Mr Leadbeater—and ordination proceeds in an actual continuation, in an absolutely correct progress; they actually have created a "family tree" by it. I don't want to talk about the start of the "family tree" but you must accept that if it would be a natural progression that there once was an ordained bishop in Rome who dropped away, who then however ordained all the others, so all these Theosophical luminaries would refer back to a real descent of their priesthood to that which once existed. Therefore, awareness of this succession is everywhere present and such things are, according to their understanding, taken completely as the reality. [ 18 ] Something like this must be taken as a reality within the Roman Catholic Church. The old Catholic church more or less didn't have the feeling—but within the Roman Catholic church it is certain accepted this way—that the moment the priest crosses the stole he no longer represents a single personality or attitude but he is then only a member of the church and speaks as a representative, as a member of the church. The Roman Catholic Church considered itself certainly as a closed organism, where the individual loses his individuality through ordination; they see it this way increasingly. [ 19 ] Now something else is in contrast to this. You may think about what I've said as you wish, but I can only speak from my point of view, from the viewpoint of my experience. I have seen much within the transubstantiation. Today in the Catholic Church there is quite a strict difference according to which priest would perform the transubstantiation, yet I have always seen how during the transformation, during the transubstantiation, the host takes on an aura. Therefore, I have come to recognise within the objective process, that when it is worthily accomplished, it is certainly fulfilled. I said, you may think about this as you wish, I say it to you as something which can be looked at from one hand, and on the other hand also as a basic conviction of the church being valid while it was still Catholic, when the evangelist church hadn't become a splintering off. We very soon come back to reality when we look at these things and it must even be said within the sacrament of mass being celebrated there is something like a true activity, which is not merely an outer sign but a real act. If you now take all the sacraments of mass together which had been celebrated, you will create an entirety, a whole, and this is something which stands there as a fact. It is something which certainly touches things, where the evangelical mind would say: Yes, there is something magical in the Catholic Mass.—This it does contain. It also contained within it the magical part, one can experience in the evangelist mind as something perhaps heathen. Good, talk to one another about this. In any case this underscores it as being a reality, which one can't without further ado, without approaching the bearer of this reality, celebrate a mass. I say celebrate; it can be demonstrated, one can show everything possible, but one can't celebrate with the claim that through the mass what should happen at the altar will only happen when it is read without any personal imprint, in absolute application. You see, it is ever present there where one works with the mysteries; it is simply so, when one works with the mysteries. Just as no Masonic ceremony may be carried out by a non-Mason in the consciousness of the Freemason, nor may a non-ordained person in true Catholicism work from out of Catholicism and perform with full validity the ceremony in consciousness. [ 20 ] This is where we are being directed and must consult. I want you to take note that in this case the Catholic rules were actually very strict. Please don't take things up in such a way as if I am saying this towards pro-Catholicism; I only want to point out the situation. It isn't important for us to be for, or opposed, to Catholicism, because it's about something quite different. Particular customs were very strictly adhered to in the Catholic Church—not at all what is today in Rome's mood and procedure. If a priest became so unworthy as to be excommunicated, then his skin would be ripped off, scraped off from his fingers where he had held the sacred host in his hands. His skin would be scraped off. Sometimes such things are referred to but legally it is so, and I know such processes quite well, that after the priest's excommunication the skin of the fingers which touched the host, were scraped off. You can certainly set the objective instead of the succession that goes from the apostles through the priesthood to the priest celebrating today. You can set that which goes through consecration and through the sacraments themselves. You can exclude priesthood, but you can only exclude that by taking things objectively, right to a certain degree, objectively, that the priest no longer may have skin on his fingers when he is no longer authorised to celebrate the sacrificial mass. [ 21 ] Isn't it true, if you have Catholic feeling, it is something as definite to you as two plus two making four? It is something definite according to religious feeling. When you don't have that then you as modern people must have a certain piety, which says to you the Catholic church has also just preserved the celebration of mass and if this is carried outside the circle to which it had been entrusted—other circles have not preserved the sacrifice of mass—if it is being performed in other circles it is pure theft. Real theft. These things must also be understood from such concepts. I believe to some it appears very difficult to understand what I am saying but in conclusion it has as such a certain validity which needs to be achieved through understanding. We don't have to worry about it here because you can experience the mass according to what there is to experience. As far as the training of a new ritual is concerned, it would not be disturbed at all by this, that the Catholic mass regards the mass to be something so real that it may certainly not to be removed from the field of Catholicism. [ 22 ] This is firstly something which I wanted to say during our limited time. When I speak about the mass itself, and I will do so, I will still have a few things to add. |

| 343. The Foundation Course: Prayer and Symbolism

30 Sep 1921, Dornach Translated by Hanna von Maltitz Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| In any case, real Christians need to remain within inner childlike feelings today in order to understand the Gospels in a believable way, also without criticism. When as a theologian he applies criticism, he has to, because he comes from the Christian angle, be able to understand the Gospel without criticism. |

| The 58th verse now continues with the line: "And he was not able to do many deeds of the spirit there, for the sake of their unbelief." When we understand this situation, we are immediately led to see how Christ Jesus stands amidst people who have not understood the words: "Behold, in those souls live my mother and my brothers." They failed to understand these words; as the words were not understood in their time; they also don't lead the way to Christ Jesus. |

| 343. The Foundation Course: Prayer and Symbolism

30 Sep 1921, Dornach Translated by Hanna von Maltitz Rudolf Steiner |

|---|