| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Seven

28 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| In history the important thing is the ability to form a judgment of the underlying forces and powers at work. But you must realize that the judgment of one is more mature, that of another less so, and the latter should not pass any judgment at all because nothing has been understood about the underlying forces. |

| They said among themselves, “Let us exalt Jerusalem so that it may become the center of Christianity, so that Rome no longer holds that position.” This, the underlying motive of the first Crusaders, can be conveyed to the children tactfully, and it is important to do so. |

| Then you can also tell how the pilgrims really came to understand industries found in the East at the time, and still unknown in Europe. The West was in many ways more backward than the East. |

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Seven

28 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

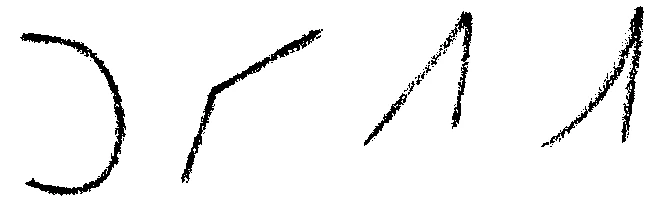

Today we will try an exercise in which we have to hold the breath somewhat longer. Speech exercise:

You can only achieve what is intended by dividing the lines properly. Then you will bring the proper rhythm to your breath. The object of this exercise is to do gymnastics with the voice in order to regulate the breath. In words like fulfilling and willing, both “l’s” must be pronounced. You shouldn’t put an “h” into the first “l”, but the two “l’s” must be sounded one after the other. You must also try to avoid speaking with a rasping voice, and develop instead tone in your voice, bringing it up from deeper in your chest, to give full value to the vowels. (All Austrians have tinny voices!) Before each of the above lines the breath should be consciously brought into order. The words that appear together also belong together when you read. You know that we usually do the following speech exercises also:

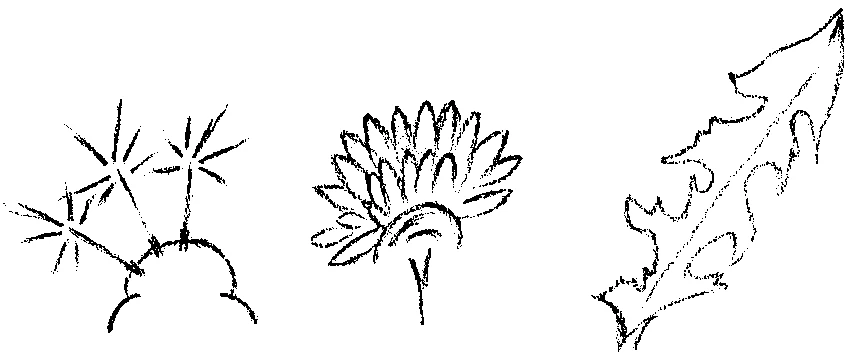

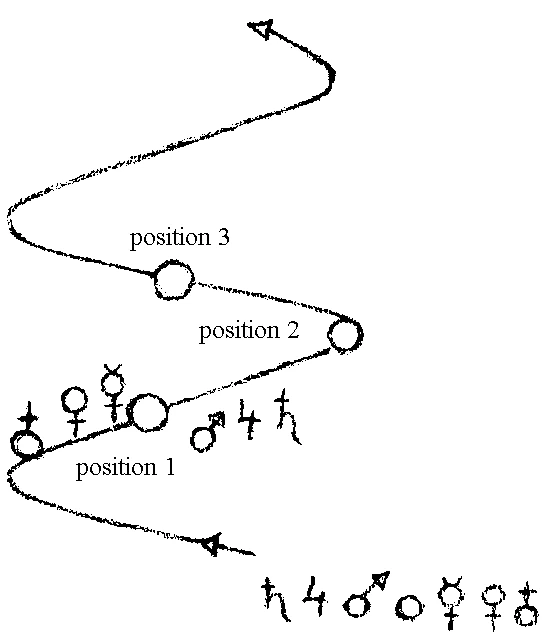

They all read the fable aloud. RUDOLF STEINER: After hearing this fable so often you will certainly sense that it is written in the particular style of fables and many other writings of the eighteenth century. You get the feeling that they didn’t quite finish, just as other things were not fully completed then. Rudolf Steiner read the fable aloud again. RUDOLF STEINER: Now, in the twentieth century the fable would be continued something like this: “That may be the honor of bulls! And if I were to seek honor by stubbornly standing still, that would not be a horse’s honor but a mule’s honor!” That is how it would be written in these days. Then the children would notice immediately that there are three kinds of honor; the honor of a bull, the honor of a horse, and the honor of a mule. The bull throws the boy, the horse carries him quietly along because that is chivalrous, the mule stubbornly stands still because that is the mule’s idea of honor. Today I would like to give you some material for tomorrow’s discussion on the subject of your lessons, since we will then consider particularly the seven-to-fourteen-year-old children.2 So we will now speak of certain things that can guide you, and after I have presented this introduction, you will only need an ordinary reference book to amplify the various facts we have spoken of in our discussions. Today we will consider not so much how to acquire the actual subject matter of our work, but rather how to cherish and cultivate within ourselves the spirit of an education that contains the future within it. You will see that what we discuss today focuses on the work in the oldest classes.3 I would therefore like to discuss what relates to the history of European civilization from the eleventh to the seventeenth century. You must always remember that teaching history to children should always contain a subjective element, and this is also true, more or less, when you work with adults. It is easy enough to say that people should not bring opinions and subjective ideas into history. You might make this a rule, but it cannot be adhered to. Take aspect of history in any country of the world; you will either have to arrange the facts in groups for yourself, or you will find them already thus assembled by others in the case of less recent history. If, for example, you want to describe the spirit of the old Germanic peoples, you will turn to the Germania of Tacitus. But Tacitus was a person of very subjective thought; the facts he presents were clearly arranged in groups. You can only hope to succeed in your task by marshalling the facts in your own personal way, or else by using what others have done in a similar way before you. You can find examples, from literature for example, to substantiate what I have said. Treitschke wrote German History of the Nineteenth Century in several volumes; it delighted Herman Grimm, who was also a competent judge, but it horrified many adherents of the entente. But when you read Treitschke you will feel immediately that his excellence is due to the very subjective coloring of his grouping of facts. In history the important thing is the ability to form a judgment of the underlying forces and powers at work. But you must realize that the judgment of one is more mature, that of another less so, and the latter should not pass any judgment at all because nothing has been understood about the underlying forces. The former, just because an independent judgment has been formed, will very well describe the actual course of history. Herman Grimm portrayed Frederick the Great, and Macaulay also portrayed him, but Macaulay’s picture is completely different. Grimm even composed his article as a kind of critique of Macaulay’s article, and speaking from his perspective he said, “Macaulay’s picture of Frederick the Great is the grotesque face of an English lord with snuff on his nose!” The only difference is that Grimm is a nineteenth-century German and Macaulay a nineteenth-century Englishman. And any third person passing judgment on both would really be very narrow-minded if one were found to be true and the other false. You might as well choose examples even more drastic. Many of you know the description of Martin Luther in the ordinary history books. If one day you try the experiment of reading it in the Catholic history books, you will get to know a Martin Luther whom you never knew before! But when you have read it you will find it difficult to say that the difference is anything but different viewpoints. Now it is just such points of view arising from nation or creed that must be overcome by future teachers. Because of this we must earnestly work so that teachers are broad-minded, so that the point will be reached of having a broad-minded philosophy of life. Such a mental attitude gives you a free and wide view of historical facts, and a skillfull arranging of these facts will enable you to convey to your pupils the secrets of human evolution. Now, when you want to give the children some idea of cultural history from the eleventh to the seventeenth centuries, you would first have to describe what led up to the Crusades. You would describe the course of the first, second, and third crusades, and how they gradually stagnated, failing to achieve what they should have. You would describe the spirit of asceticism that spread through much of Europe at the time—how everywhere, through the secularization of the church (or in any case in connection with this secularization), there arose individuals such as Bernard of Clairvaux, natures full of inner piety, such piety that it gave the impression to others that they were miracle-workers. From reference books you could try to become acquainted with biographies of people of this kind and then bring them to life for your pupils; you could try to conjure before them the living spirit that inspired those great expeditions to the East—because they were powerful in the views of the time. You would have to describe how these expeditions came to be through Peter of Amiens and Walter the Penniless, followed by the expedition of Godfrey of Bouillon and others. Then you could relate how these Crusades set out toward the East and how enormous numbers of people perished, often before they reached their destination. You can certainly describe to boys and girls of thirteen to fifteen how these expeditions were composed, how they set out without any organization and made their way toward the East, and how many perished because of unfavorable conditions, and having to force their way through foreign countries and peoples. You will then have to describe how those who reached the East had a certain degree of success at first. You can speak of what Godfrey of Bouillon accomplished, but you will also have to show the contrast that arose between the Crusaders of the later Crusades and Greek policy—how the Greeks became jealous of what the Crusaders were doing, feeling that the Crusaders’ goals were contrary to what the Greeks themselves were planning to do in the East; how fundamentally the Greeks, as much as the Crusaders, wanted to absorb the interests of the East into their own sphere of interests. Paint a graphic picture of how the goals of the Crusaders roused the Greeks’ opposition. Then I suggest that you describe how the crusading armies in the East, instead of taking up arms against the Eastern peoples in western Asia, began to fight among themselves; and how the European peoples themselves, especially the Franks and their neighbors, began to quarrel about their claims to conquests and even took up arms against each other. The Crusades originated in fiery enthusiasm, but the spirit of inner discord seized those who took part in them; furthermore, antagonism arose between the Crusaders and the Greeks. In addition to all this, at the very time of the Crusades we find opposition between church and state, and this became more and more evident. It may also be necessary to acquaint the children with something that is true, although in all its essential points it is veiled by the bias of historical writers. Godfrey of Bouillon, the leader of the first Crusade, really intended to conquer Jerusalem in order to balance the influence of Rome. He and his companions did not say this openly to the others, but in their hearts they carried the battle cry, “Jerusalem versus Rome!” They said among themselves, “Let us exalt Jerusalem so that it may become the center of Christianity, so that Rome no longer holds that position.” This, the underlying motive of the first Crusaders, can be conveyed to the children tactfully, and it is important to do so. Those were great tasks that the Crusaders undertook, and great too were the tasks that gradually arose from the circumstances themselves. Little by little it came to be that the Crusaders were not great enough to bear the burden of such tasks without harm to themselves. And so it happened that, at the time of the fiercest battles, licentiousness and immorality gradually broke out among the Crusaders. You can find these facts in any history book, and they serve to illustrate the general course of events. You will notice that in my arrangement of facts today, I am actually describing them without bias, and I will try also to describe in a purely historical way what took place in Europe from the eleventh to the seventeenth century. It is often possible to make history clear through hypothesis, so let’s suppose that the Franks had conquered Syria and had established a Frankish dominion there—that they had reached an understanding with the Greeks, had left room for them, and had relinquished to them the rule of the more western portion of Asia Minor. Then the ancient traditions of the Greeks would have been fulfilled and North Africa would have become Greek. A counterbalance to subsequent events would have thus been established. The Greeks would have held sway in North Africa, the Franks in Syria. Then they wouldn’t have quarrelled with each other, and thus they wouldn’t have forfeited their dominions, and the invasions of the worst Eastern peoples—the Mongols, the Mamelukes, and Turkish Ottoman—would have been prevented. Because of the immorality of the Crusaders, and inevitably their inability to rise to their tasks, the Mongols, Mamelukes, and Ottomans overran the very regions that the Crusaders were attempting to “Europeanize.” And so we see how the reaction toward the great enthusiasm that led to the Crusades, spread over vast regions, is counterattacked from the other side. We see the Moslem-Mongolian advance, which set up military tyrants, and which for a long time remained the terror of Europe and cast a dark shadow over the history of the Crusades. You see, by describing such things and acquiring the necessary pictorial descriptions from reference books, you can awaken in the children themselves pictures of the progress of civilization—pictures that will live on in them. And that is the important thing—that the children be given these pictures. They will initially be conjured in their minds through your graphic descriptions. If you can then show them some works of art, notable paintings from this period, you will find this supports what you say. Thus, you will make it clear to the children what happened during the Crusades, and enable them to make their own mental pictures of these events. You have shown them the dark side of the picture, the terror caused by the Mongolians and Moslems, and now it will be well to add the other side, the good things that developed. Describe vividly to the children how the pilgrims who had migrated east, came to understand many new things there. Agriculture, for example, was at that time very backward in Europe. In the East it was possible for these Western pilgrims to learn a much better way of farming their land. The pilgrims who reached the East and afterward returned to Europe (and many did return), brought with them a skilled knowledge of agricultural methods, which raised the standard of agricultural production considerably. The Europeans owed this to the experience that the pilgrims brought back with them. You must describe this to the children so graphically that they actually see it there before them—how the wheat and other cereals flourished less before the Crusades, how they were smaller, more sparse, the ears less full, and how after the Crusades they were much fuller. Describe all this in pictures! Then you can also tell how the pilgrims really came to understand industries found in the East at the time, and still unknown in Europe. The West was in many ways more backward than the East. What grew and flourished in such a fine way in the industrial activity of the Italian towns and other places further north, was all due to the Crusades; we also have to thank them for a new artistic impulse. Thus you can call on pictures of the cultural and spiritual progress of that time. There is something else you can describe to the children: you can say to them, “You see, children, that was when the Europeans came to know the Greeks; they had fallen away from Rome in the first thousand years after Christ, but had remained Christians. All over the West people believed that no one could be a Christian without viewing the Pope as the head of the church.” Now explain to the children how the Crusaders, to their astonishment and edification, learned that there were other Christians who did not acknowledge the Roman Pope. This freeing of the spiritual side of Christianity from the temporal church organization was something very new at the time. This is something you can explain to the children. Then you can tell them that even among the Moslems, who could scarcely have been called very pleasant denizens of the world, there were also noble, generous, and brave people. And so the pilgrims came to know people who could be brave and generous without being Christians; thus a person could even be good and brave without being a Christian. For the Europeans of that time this was a great lesson that the Crusaders brought with them when they returned to Europe. During their stay in the East they gained many things that they brought back to Europe to further its spiritual progress. You can then continue, “Just imagine, children, there was a time when the Europeans had no cotton cloth, they did not even have a word for it; they had no muslin—that too is an Eastern word; they could not lie down or laze about on a sofa, for sofas and the word for them were brought back by the Crusaders. They had no mattresses either. Mattress is also an Asian word. The bazaar also belongs to the East, and this suggests immediately an entirely new view of the public display of goods, and it initiated large scale exhibitions of goods. Bazaars (of an Eastern kind) were very common in the East, but there was nothing of the kind in Europe before the Europeans went on their Crusades. Even the word magazine [the word for “storeroom” in German] bound up though it now is with our trade life, was not originally European; the use of great warehouses to meet the growth of trade is something that the Europeans learned from the Asians. “Just imagine,” you can say to the children, “how restricted life was in Europe; they hadn’t even any warehouses. The word arsenal too has the same origin. But now look; there is something else that the Europeans learned from the East and that is expressed in the word tariff. Until the thirteenth century the European peoples knew very little about tax-paying. But payment of taxes according to a tariff, the payment of all kinds of duties, was not introduced into Europe until the Crusaders learned about it from the Asians. “Thus you see that a great number of things were changed in Europe due to the Crusades. Not much of what the Crusaders intended to do was realized, but other things were brought about, and transformations of all kinds occurred in Europe as a result of what was learned in the East. And further, this was all connected with what they observed of the Eastern political life. Political life—the state as such—developed much earlier in the East than in Europe. Before the Crusades the forms of government in Europe were much freer than they were afterward. Because of the Crusades it also happened that wide areas were grouped together as political units.” Always assuming that the children are of the age I indicated, you can now say to them, “You have already learned in your history lessons that in former times the Romans became rulers over many lands. When they were extending their dominions, at the beginning of the Christian era, Europe was very poor and becoming even poorer. What was the cause of this increasing poverty? The people had to hand over their money to others. Central Europe will become poor again today because it must also hand over its money to others. At that time the Europeans had to give up their money to the Asiatics; the bulk of their money went to the borders of the Roman Empire. Due to this, barter became more and more the custom, and this is something that might happen again, sad though it would be, unless people rouse themselves to seek the spirit. Nevertheless, amid this poverty the ascetic, devotional spirit of the Crusades evolved. “Through the Crusades, therefore, in faraway Asia, Europeans learned to know all kinds of things—industrial production, agriculture, and so on. In this way, they could again produce things that the Asians could buy from them. Money traveled back again. Europe became increasingly rich during the Crusades. This growth of wealth in Europe occurred through the increase in its own productions; that is a further result of the Crusades. The Crusades are indeed migrations of peoples to Asia, and when the Crusaders returned to Europe they brought with them a certain ability. It was due only to this ability and skill that Florence, Italy arose and became what it did, and also due to this, such figures as Dante and others emerged.” You see how necessary it is to allow impulses of this kind to permeate your history lessons. When it is said today that more should be taught about the history of civilizations, people think they should give dry descriptions of how one thing arises from another. But even in these lower classes, history should be described by a teacher who really lives in the subject, so that through the pictures created for the children, this period of history will live again before them. You can conjure the picture of a poverty-stricken Europe, with acres of poor and sparsely sown crops, where there were no towns—only meager farms in poor condition. Nevertheless, an enthusiasm for the Crusades arises out of this same poor Europe. But then you will have to tell them how the people found this task beyond their powers and they began to quarrel and fall into evil ways, and even when they were back in Europe discord and dissension arose again. The real purpose of the Crusades was not achieved; on the contrary, the ground was prepared for the Moslems. But the Europeans learned many things in the East: how towns—flourishing towns—arise, and in the towns a rich spiritual life and culture; agriculture improved and the fields became more fertile, the industries flourished, and a spiritual life and culture arose. You will try to present all this to the children in graphic pictures and explain to them that, before the Crusades, people did not lounge on sofas! There was no bourgeois life at that time with sofas in the best parlors and all the rest of it. Try to make all these historical pictures live for the children, and then you will give them a truer kind of history. Show how Europe became so poor that people had to resort to bartering goods, and then it became rich again because of what people learned in the East. This will bring life into your history lessons! One is often asked these days what history books to read—which historian is best? The reply can only be that, in the end, each one is the best and the worst; it really makes no difference which historical author you choose. Do not read what is written in the lines, but read between the lines. Try to allow yourselves to be inspired so that, through your own intuitive sense, you can learn to know the true course of events. Try to acquire a feeling for how a true history should be written. You will recognize from the style and manner of writing which historian has found the truth and which has not. You can find many things in Ranke.4 But what we are trying to cultivate here is the spirit of truth and reality, and when you read Ranke in the light of this spirit of truth, you find that he is very painstaking but that his descriptions of characters reduce them to mere shadows; you feel as though you could pass through them, because they have no substance—they are not flesh and blood, and you might well say that you don’t want history to be a series of mere phantasms. One of the teachers recommended Lamprecht.5 Rudolf Steiner: Yes, but in him you have the feeling that he does not describe people, but figures of colored cardboard—except that he paints them with the most vivid colors possible. They are not human beings, but merely colored cardboard. Now Treitschke on the other hand is admittedly biased, but his personalities do really stand on their two feet!6 He places people on their feet, and they are flesh and blood—not cardboard figures like those of Lamprecht, nor are they mere shadowy pictures as with Ranke. Unfortunately Treitschke’s history only covers the nineteenth century. But, to get a feeling for truly good historical writing, you should read Tacitus.7 When you read Tacitus, everything is absolutely alive. When you study the way Tacitus portrays a certain epoch of history—describing the people as individuals or in groups—and allow all of this to affect your own sense of reality, it exists for you as real as life itself! Beginning with Tacitus, try to discover how to describe other periods as well. Of course you can’t read what is out of date, otherwise the fiery Rotteck would always be very good.8 But he is dated, not merely because of the facts, but in his whole outlook; he considers as gospel the political constitution of the Baden of his time, as well as liberalism. He even applies them to Persian, Egyptian, and Greek life, but he always writes with such fire that one cannot help wishing there were many historians like Rotteck today. If, however, you study the current books on history (with a sharp eye for what is often left out), you will gain the capacity to give children living pictures of the process of human progress from the eleventh to the seventeenth centuries. And, for your part, you can omit much that is said in these histories about Frederick Barbarossa, Richard Coeur de Leon, or Frederick II. Much of this is interesting but not particularly significant for real knowledge of history. It is far more important to communicate to the children the great impulses at work in history. We can continue now to the question of how to treat a class where several boys and girls have developed a foolish kind of adoration for the male or female teacher. Idolization of this kind is not really unhealthy until the age of twelve to fourteen, when the problem becomes more serious. Before fourteen it is especially important not to take these things too seriously and to remember that they often disappear again very quickly. Various suggestions made by those present.RUDOLF STEINER: I would consider that exposing the children to ridicule in front of the class is very much a two-edged sword, because the effect lasts too long, and the child will lose a connection with the class. If you ridicule children it is very difficult for them to regain the proper relationship with the rest of the class. The result is usually that the children succeed in being removed from the school. Prayer was mentioned, along with other possible ways of helping these children. RUDOLF STEINER: You are quite right! It was suggested that one might speak to the child and attempt to divert such affection. RUDOLF STEINER: The principle of diverting the devotion and capacity for enthusiasm into other channels is proper—except that you will not gain much by talking with such children, because that is exactly what they want. Precisely because this foolish adoration arises much more from feelings—and even passions—than from thinking, it would be extremely difficult to work against it effectively by being with the child frequently. It is certainly true that unhealthy feelings of this kind are due to the qualities of enthusiasm and devotion having taken the wrong path—enthusiasm in the gifted children and devotion in the less gifted. The whole thing is not very important in itself, but it will have repercussions in the way the children participate in the lessons, and this is the more serious aspect. When all of the children are affected by this foolish adoration, it is not so serious and will not last long; it will soon disappear. The class gets ideas that do not materialize; this leads to disappointment, and then the thing dies naturally. In this case it could be very good to tell a humorous story to the whole class. It only becomes detrimental when groups of children yield to this unwholesome idolization. It became necessary to think this matter over thoroughly, because it can play a role in the entire life of the school. Affectionate attachment is not so bad in itself, but it weakens the children when it becomes unhealthy. The children become listless and lethargic. In some cases it can lead to serious conditions of weakness in the children. It is a very subtle and delicate matter, because the treatment could result in turning the children’s feelings toward the exact opposite—into hatred. In some cases it could be very good to say, “You look too warm. Perhaps you should go outside for five minutes. In any case, this problem should be handled individually and each child treated individually. You should try anything that common sense tells you may help. There is one thing however that you should be extremely careful about—that such children do not get the idea that you notice their adoration. You really have to acquire the art of making them think you are unaware of it. Even when you take steps to cure them, the children should think you are merely acting normal. Let’s suppose that several children have this foolish feeling for a man who has four, five, maybe six children of his own. In this case he has the simplest remedy; he can invite the “adoring” children to go for a walk with him and bring his own children along. This would be a very good remedy. But the children should not know why they were invited. You should use concrete things like this. In a situation like this, it’s most important that you yourself act correctly, not treating those children who idolize you any differently than the others. When you remain unaffected by such foolish behavior, it disappears after awhile. It becomes serious, however, when a certain antipathy replaces adoration. This can be minimized by ignoring it. Don’t let the children know you have noticed anything, because if you call them on it or ridicule them in front of the class, the hatred will be that much greater. If you tell a story it must appear as though you would have told it anyway, otherwise certain antipathy will certainly arise afterward as a result; that can’t be avoided. But when you work with the same class for several years you will be able to restore a normal sympathy over time. You cannot prevent another consequence, either, because when this foolish adoration assumes a serious form, the children will be somewhat weakened by it. When it is finished, you must help them to get over this weakness. This will indeed be the best therapy that you can apply. You can make use of all the other remedies—sending the children out for five minutes, taking them for walks, and so on, but your attitude must always be to ignore the whole matter in a healthy way. The child will be somewhat weakened, and afterward the teacher will be able to help the child through love and affection. If the matter were to become very serious, the teacher, because of being the object of adoration, could not do much; such a teacher would then have to seek the advice and help of others. Tomorrow’s subject has to do with actual teaching rather than educational principles as such. Will each of you imagine that several children in your class are not doing very well in one subject or another—for example, arithmetic, languages, natural history, gymnastics, or eurythmy. How, through special treatment of the children’s human capacities, would you try to meet a misfortune of this kind during the early school years? How could you use the other subjects to help you?

|

| Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Eight

29 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| If you repeat a cure of this kind several times over the year, you will see that the powers of a fairly young child undergo a change. This applies to the first years of school life. I ask you to consider this very seriously. |

| Then there is also another way of possibly helping children to grasp forms: have them understand from inside what they cannot grasp from outside. Let’s suppose, for example, that a child cannot understand a parallelepiped from outside. |

| In that case you can help the child to understand merely by letting the imagination see that a small thing is very large indeed. Have the child repeatedly try to picture some little yellow crystal as a gigantic crystallized form. |

| Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Eight

29 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Speech Exercise:

RUDOLF STEINER: The first four sentences have a ring of expectation, and the last line is a complete fulfillment of the first four. Now let’s return to the other speech exercise:

RUDOLF STEINER: You can learn a great deal from this. And now we will repeat the sentence:

RUDOLF STEINER: Also there is a similar exercise I would like to point out that has more feeling in it. It consists of four lines, which I will dictate to you later. The touch of feeling should be expressed more in the first line:

RUDOLF STEINER: You must imagine that you have a green frog in front of you, and it is looking at you with lips apart, with its mouth wide open, and you speak to the frog in the words of the last three lines. In the first line, however, you tell it to lisp the lovely lyrics “Lulling leader limply.” This line must be spoken with humorous feeling; you really expect this of the frog. And now I will read you a piece of prose, one of Lessing’s fables.1

RUDOLF STEINER: What is the moral of this fable? Someone suggested: That it is not until someone is dead that we see how great that person was. Another suggested: That, until the great are overthrown, the small do not recognize what they were. Rudolf Steiner: But why then choose the fox, who is so cunning? Because the cunning of the fox cannot compare with the magnificence of the tree. RUDOLF STEINER: In which sentence would you find the moral of the fable in relation to the cunning of the fox? “I never would have thought it was so big!” The point is, he had never even looked up; he had run round the bottom of the trunk, which was the only part of the tree he had noticed, and here the tree had only taken up a small space. Despite cunning, the fox had only seen what is visible around the foot of the tree. Please notice that fables—which by their very nature are enacted in their own special world—can be read realistically, but poems never. Now the problem I placed before you yesterday brings us something of tremendous importance, because now we must consider what measures to take when we notice that one group of children is less capable than another in one or another subject or lesson. I will ask you to choose from any part of the period between six and fourteen, and to think especially of, let’s say, a group of children who cannot learn to read and write properly, or those who cannot learn natural history or arithmetic, or geometry or singing. Consider what course you will pursue in the class, or in your general treatment of the children, both now and later on, so that you can correct such shortcomings as much as possible. Several teachers contributed detailed suggestions. RUDOLF STEINER: The examples you mention might arise partially from general incompetence. On the other hand, it could also be a question of a particular lack of talent. You could have children who are perhaps extraordinarily good at reading and writing, but as soon as they come to arithmetic they do not demonstrate any gift at all for it. Then there are those who are not so bad at arithmetic, but the moment you begin to call on their power of judgment, such as in natural science, their powers are at an end. Then again there are children who have no desire to learn history. It is important to notice these specific difficulties. Perhaps you can find a remedy in this way: When you notice that a child, right from the beginning, has little talent for reading and writing, you would do well, anyway, to get in touch with the parents and ask them immediately to keep the child off eggs, puddings, and pastry as much as possible. The rest of the diet can remain more or less as it was. When the parents agree to try to provide the child with a really good wholesome diet, however—omitting the items of food mentioned above—they might even cut down on the meat for awhile and give the child plenty of vegetables and nourishing salads. You will then notice that, through a diet like this, the child will make considerable gains in ability. You must take advantage of this improvement, and keep the child very busy when the diet is first changed. But if you notice that a mere change of diet doesn’t help much, then, after you have talked it over with the parents, try for a short while, perhaps a week, to keep the child entirely without food for the whole morning, or at least the first part of the morning when the child should be learning to read and write—to allow learning on an empty stomach—or maybe give the child the minimum of food. (You should not continue too long with this method; you must alternate it with normal eating.) You must make good use of this time, however, when the capacities will most certainly be revealed, and the child will show greater ability and be more receptive to what you are teaching. If you repeat a cure of this kind several times over the year, you will see that the powers of a fairly young child undergo a change. This applies to the first years of school life. I ask you to consider this very seriously. Generally speaking, you should be very aware that the foolish ways many parents feed their young children contributes greatly to the lessening of their faculties, especially with phlegmatic and sanguine children. Perpetually overfeeding children—and this is somewhat different at the present time,2 but you should know these things—stuffing them with eggs, puddings, and starchy foods is one of the things that makes children unwilling to learn and incapable of doing so during the early years of their school life. A teacher asked about cocoa. RUDOLF STEINER: Why should children drink cocoa at all? It is not the least bit necessary except to regulate digestion. Things like this are needed sometimes for this purpose, and cocoa is better than other remedies for children whose digestion works too quickly, but it should not be included otherwise in children’s diet. These days children are given many things that are unsuitable for them. You can experience some very strange things in regard to this. When I was a teacher in the eighties, there was a young child in the house; I did not actually teach him, since I had only the older children; he was a little cousin. He was really a nice lovable child with bright ideas. He could have become a gifted pupil. I saw him a good deal and could observe for myself how witty and gifted the child was. One day at table this little fellow—although he was scarcely two years old—had two little dumplings, and when someone said to him, “Look Hans, now you already have two dumplings,” he was clever enough to answer, “And the third will follow in a minute.” That’s what the little tyke said! Then another thing: he was very fond of calling people bad names. This did not seem very important to me in a child of that age—he would soon grow out of it. He had gotten into the habit of being particularly abusive to me. One day as I was coming in the door (he was a little older by this time) he stood there and blocked the way. He couldn’t think of any name bad enough for me, so he said: “Here come two donkeys!” That was really very smart of him, wasn’t it? But the boy was pale; he had very little appetite and was rather thin. So, on the advice of an otherwise excellent doctor, this child was given a small glass of red wine with every meal. I was not responsible for him and had no influence in this extraordinary way of treating a child’s health, but I was very concerned about it. Then in his thirty-second or thirty-third year I saw this individual again; he was a terribly nervous man. When he was not present I enquired what he had been like as a schoolboy. This restless man, although only in his thirties, had become very nervous, and demonstrated the lamentable results of that little glass of red wine given to him with his meals as a boy. He was a gifted child, for a child who says “Here come two donkeys” really shows talent. Frau Steiner interjected, “What an impudent boy!” RUDOLF STEINER: We needn’t bother with impudence, but how does this really come about? It’s amazing. He can find no word bad enough, and so he makes use of number to help him. That shows extraordinary talent. But he became a poor scholar and never wanted to learn properly. Thus, because of this method of treatment—giving him wine as a young child—he was completely ruined by the time he was seven years old. This is what I want to impress upon you at the beginning of our talk today—that, in relation to a child’s gifts and abilities, it is not the least unimportant to consider how to regulate the diet. I would especially ask you, however, to see that the child’s digestion does not suffer. So when it strikes you that there is something wrong with a child’s capacities, you must in some tactful way find out from the parents whether or not the child’s digestion is working properly, and if not you should try to put it in order. Someone spoke about the children who are not good at arithmetic. Rudolf Steiner: When you discover a special weakness in arithmetic, it would be good to do this: generally, the other children will have two gymnastics lessons during the week, or one eurythmy lesson and one gymnastics lesson; you can take a group of the children who are not good at arithmetic, and allow them an extra hour or half-hour of eurythmy or gymnastics. This doesn’t have to mean a lot of extra work for you: you can take them with others who are doing the same kind of exercises, but you must try to improve these children’s capacities through gymnastics and eurythmy. First give them rod exercises. Say to them, “Hold the rod in your hand, first in front counting 1, 2, 3, and then behind 1, 2, 3, 4." Each time the child must change the position of the rod, moving it from front to back. A great effort will be made in some way to get the rod around behind at the count of 3. Then add walking: say, 3 steps forward, 5 steps back; 3 steps forward, 4 steps back; 5 steps forward, 3 steps back, and so on. In gymnastics, and also perhaps in eurythmy, try to combine numbers with the children’s movements, so they are required to count while moving. You will find this effective. I have frequently done this with pupils. But now tell me, why does it have an effect? From what you have already learned, you should be able to form some ideas on this subject. A teacher commented: Eurythmy movements must be a great help in teaching geometry. RUDOLF STEINER: But I did not mean geometry. What I said applied to arithmetic, because at the root of arithmetic is consciously willed movement, the sense of movement. When you activate the sense of movement in this way, you quicken a child’s arithmetical powers. You bring something up out of the subconscious that, in such a child, is unwilling to be brought up. Generally speaking, when a child is bad both at arithmetic and geometry, this should be remedied by movement exercises. You can do a great deal for a child’s progress in geometry with varied and inventive eurythmy exercises, and also through rod exercises. Comment: Where difficulties exist in pronunciation, the connection between speech and music should be considered. RUDOLF STEINER: Most cases of poor pronunciation are due to defective hearing. Comment: Sanguine students do not follow geography lessons very well because their ideas are vague. I recommend taking small portions of a map as subjects for drawing. RUDOLF STEINER: When you make your geography lessons truly graphic, when you describe the countries clearly and show the distribution of vegetation, and describe the products of the earth in the different countries, making your lessons thoroughly alive in this way, you are not likely to find your students dull in this subject. And when you further enliven the geography lessons by first describing a country, then drawing it—allowing the children, to draw it on the board and sketch in the rivers, mountains, distribution of vegetation, forest, and meadow land, and then read travel books with your pupils—when you do all this you find that you usually have very few dull scholars; and what’s more, you can use your geography lessons to arouse the enthusiasm of your pupils and to stir up new capacities within them. If you can make geography itself interesting you will indeed notice that other capacities are aroused also in your pupils. Comment: I have been thinking about this problem in relation to the first three grades. I would be strict with lazy children and try to awaken their ambition. In certain cases children must be told that they might have to go through the year’s work a second time. Emulation and ambition must be aroused. RUDOLF STEINER: I wouldn’t recommend you to give much credit to ambition, which cannot generally be aroused in children. In the earliest school years you can make good use of the methods you suggest, but without overemphasizing ambition, because you would then later have to help the child to get rid of it again. But you must primarily consider food and diet, and I need to say this again and again. Perhaps the friends who speak next will consider the fact that there are many children who in later life have no power of perceiving or remembering natural objects properly. A teacher may despair over some pupils who can never remember which among a number of minerals is a malachite or a hornblende, or even an emerald—who really have no idea of how to comprehend natural objects and recognize them again. The same is true also in relation to plants and animals. Please keep this in mind also. Comment: I have noticed that with the youngest children you often find some who are backward in arithmetic. I like best to illustrate everything to them with the fingers, or pieces of paper, balls, or buttons. One can also divide the class without the children knowing anything about it; they are divided into two groups, the gifted ones and the weaker ones. We then take the weaker ones alone so that the gifted children are not kept back. RUDOLF STEINER: In that case, Newton, Helmholtz, and Julius Robert Mayer would have been among the backward ones! That doesn’t matter. RUDOLF STEINER: You are right. It doesn’t matter at all. Even Schiller would have been among the weaker ones. And according to Robert Hamerling’s teaching certificate, he passed well in practically everything except German composition; his marks for that subject were below average!3 We have heard how eurythmy can help, and now Miss F. will tell us how she thinks eurythmy can be developed for the obstinate children, for they too must learn eurythmy. Miss F.: I think melancholic children would probably take little interest in rhythmic exercises and rod exercises, beating time or indeed any exercise that must be done freely, simply, and naturally. They like to be occupied with their own inner nature, and they easily tire because of their physical constitution. Perhaps, when the others are doing rod exercises these children could accompany them with singing, or reciting poems in rhythm. In this way they will be drawn into the rhythm without physical exertion. But it is also possible that melancholic children may dislike these exercises, because they have the tendency to avoid entering wholeheartedly into anything, and always withhold a part of their being. It would be good, therefore, to have them accompany the tone gestures with jumps, because the whole child must then come into play, and at the same time such gestures are objective. The teacher must never feel that the child cannot do this, but instead become conscious that eurythmy, in its entirety, is already in the child. Such assurance on the part of the teacher would also be communicated to the child. RUDOLF STEINER: These suggestions are all very good. With regard to the children who resist doing eurythmy, there is still another way to get them to take pleasure in it. Besides allowing them to watch eurythmy frequently, try to take photographs of various eurythmy positions. These must be simplified so that the child will get visual images of the human being doing eurythmy forms. Pictures of this kind will make an impression on the children and kindle their abilities in eurythmy. That was why I asked Miss W. to take pictures of this kind (I don’t mean mere reproductions of eurythmy positions, but transformed into simple patterns of movement that have an artistic effect). These could be combined to show children the beauty of line. You would then discover an exceptionally interesting psychological fact—that children could perceive the beauty of line that they produced themselves in eurythmy, without becoming vain and coy. Although children are likely to become vain if their attention is drawn to what they have themselves done, this is not the case in eurythmy. In eurythmy, therefore, you can also cultivate a perception of line that can be used to enhance the feeling of self without awakening vanity and coquettishness. Someone spoke of how he would explain the electric generator to children. He would try to emphasize in every possible way what would show the fundamental phenomenon most clearly. RUDOLF STEINER: That is a very important principle, and it is also applicable to other subjects. It is a good principle for teaching, but to a certain extent it applies to all children in the physics lessons. It has no direct connection with the question of dealing with backward pupils. In physics the backward ones, especially the girls, are certain to put up a certain amount of opposition, even when you show them a process of this kind. Question: Since food plays such a very important role, would Dr. Steiner tell us more about the effect of different foods on the body. RUDOLF STEINER: I have already spoken of this, and you can also find many references in my lectures. It would perhaps lead us too far afield today to go into all the details of this subject, but most of all one should avoid giving children such things as tea and coffee. The effect of tea on our thoughts is that they do not want to cohere; they flee from one another. For this reason tea is very good for diplomats, whose job in life is just to keep talking, with no desire to develop one thought logically out of another. You should avoid sending children’s thoughts into flight by allowing them to indulge in tea. Neither is coffee good for children, because it disposes them to become too pedantic. Coffee is a well-known expedient for journalists, because with its help they can squeeze one thought out of another, as it were. This would not be the right thing for children, because their thoughts should arise naturally, one from another. Coffee and tea are among the things to be avoided. The green parts of a plant and also milk may be considered especially important food for children, and they should have white meat only, as far as possible. Comment: When a child has difficulty in understanding, the teacher should offer a great deal of individual help, and should also inquire about how the child does in other subjects; but if too much time is spent with the duller children, the difficulty would arise that the others are left unoccupied. RUDOLF STEINER: Please do not overestimate what the other children lose because of your work with the less gifted ones. As a rule, not much is lost provided that, while you present a subject properly for the duller children, you also succeed in getting the brighter ones to pay attention to it also. There is really then no serious loss for the more talented children. When you have a right feeling for the way in which a subject should be introduced for the weaker ones, then in one way or another the others will profit by it. Comment: Whenever there is lack of interest, I would always have recourse to artistic impressions. I know of one child who cannot remember the forms of different minerals—in fact he finds it difficult to form a mental image of any type of formation. Such children cannot remember melodies either. RUDOLF STEINER: You have discovered the particular difficulty found in children who have no perception of forms and no power of retaining them in memory. But you must distinguish between forms related to the organic world and those connected with minerals, which in fact run parallel to the forms of melodies. The important thing is that here we touch on a very, very radical defect, a great defect in the development of the child, and you must consider seriously how this defect can be fundamentally healed. There is an excellent way of helping these children to remember organic forms in nature—the forms of plants and animals; draw caricatures for them that emphasize the characteristics of a particular animal or plant. These drawings must not be ugly or in bad taste, but artistic and striking; now have the children try to remember these caricatures so that, in this roundabout way through caricature, they begin to find it easier to remember the actual forms. You could, for example, draw a mouse for them like this. Give it teeth and whiskers too if you like!  Then there is also another way of possibly helping children to grasp forms: have them understand from inside what they cannot grasp from outside. Let’s suppose, for example, that a child cannot understand a parallelepiped from outside.4 The child cannot remember this form. You say to the child: imagine you are a tiny little elf, and that you could stand inside of this form as if it were a room. You allow the child to grasp from inside what cannot be understood from outside. This the child can do. But you must repeat this again and again. With forms of this kind, which also appear in minerals, this is relatively easy to do, but it is not as easy when it comes to perceiving color or any other quality of the mineral. In that case you can help the child to understand merely by letting the imagination see that a small thing is very large indeed. Have the child repeatedly try to picture some little yellow crystal as a gigantic crystallized form. When you are dealing with the element of time, however—in music, for example—it is not such an easy matter. Let us for the moment suppose that you have not yet made any progress in improving the children’s grasp of spatial forms. Now, however, if you want to use caricature in musical form, you will only succeed when you introduce an arithmetical process, making the intervals infinitely larger and drawing out each sound for a very long time; thus by greatly increasing the time between each sound, you can produce the melody on a much larger scale, which will have an astonishing effect on the children. In this way you will achieve something, but otherwise you will not be able to effect much improvement. Questions for tomorrow: 1. How can I treat the higher plants from a natural-scientific viewpoint in the same spirit shown yesterday for the animals, for cuttlefish, mouse, and human beings?5 2. How can I introduce mushrooms, mosses, and lichens into these lessons? These two questions can perhaps be answered together. It is a case of applying the same methods for the plants as those I spoke of yesterday. It is not a question of object lessons, but of the proper teaching after the ninth year, when natural history is introduced into the curriculum.

|

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Nine

30 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Then too you must not forget to give the children the kind of image of the plant’s actual form that they can understand. Comment: The germinating process should be demonstrated to the children—for example, in the bean. |

| Children cannot have a direct perception of a metamorphosis theory, but they can understand the relationship between water and root, air and leaves, warmth and blossoms. It is not good to speak about the plants’ fertilization process too soon—at any rate, not at the age when you begin to teach botany—because children do not yet have a real understanding of the fertilization process. |

| Later, when the children are grown, they will much more easily understand how senseless it is to believe that human existence, as far as the soul is concerned, ceases every evening and begins again each morning. |

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Nine

30 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Speech exercise.

Rudolf Steiner: This sentence is constructed chiefly to show the break in the sense, so that it runs as follows: First the phrase “Deprive me not of what,” and then the phrase “pleases you,” but the latter is interrupted by the other phrase, “when I give it to you freely.” This must be expressed by the way you say it. You must notice that the emphasis you dropped on the word “what” you pick up again at “pleases you.”

Weekly verse from The Calendar of the Soul:

RUDOLF STEINER: Now we arrive at the difficult task before us today. Yesterday I asked you to consider how you would prepare the lessons in order to teach the children about the lower and higher plants, making use of some sort of illustration or example. I have shown you how this can be done in the case of animals—with a cuttlefish, a mouse, a horse, and a person—and your botany lessons must be prepared in the same spirit. But let me first say that the correct procedure is to study the animal world before coming to terms with the natural conditions of the plants. In the efforts necessary to characterize the form of your botany lessons—finding whatever examples you can from one plant or another—you will become clear why the animal period must come first. Perhaps it would be a good idea if we first ask who has already given botany lessons. That person could speak first and the others can follow. Comment: The plant has something like an instinctive longing for the Sun. The blossoms turn toward the Sun even before it has risen. Point out the difference between the life of desire in animals and people, and the pure effort of the plant to turn toward the Sun. Then give the children a clear idea of how the plant exists between Sun and Earth. At every opportunity mention the relation of the plant to its surroundings, especially the contrast between plants and human beings, and plants and animals. Talk about the outbreathing and in-breathing of the plant. Allow the children to experience how “bad” air is the very thing used by the plant, through the power of the Sun, to build up again what later serves as food for people. When speaking of human dependence on food you can point to the importance of a good harvest, and so on. With regard to the process of growth it should be made clear that each plant, even the leaf, grows only at the base and not at the tip. The actual process of growth is always concealed. RUDOLF STEINER: What does it actually mean that a leaf only grows at the base? This is also true of our fingernails, and if you take other parts of the human being, the skin, the surfaces of the hands, and the deeper layers, the same thing applies. What actually constitutes growth? Comment: Growth occurs when dead matter is “pushed out” of what is living. RUDOLF STEINER: Yes, that’s right. All growth is life being pushed out from inside, and the dying and gradual peeling off of the outside. That is why nothing can ever grow on the outside. There must always be a pushing of substance from within outward, and then a scaling off from the surface. That is the universal law of growth—that is, the connection between growth and matter. Comment: Actually the leaf dies when it exposes itself to the Sun; it sacrifices itself, as it were, and what happens in the leaf also happens at a higher level in the flower. It dies when it is fertilized. Its only life is what remains hidden within, continuing to develop. With the lower plants one should point out that there are plants—mushrooms, for example—that are similar to the seeds of the higher plants, and other lower plants resemble more particularly the leaves of the higher plants. RUDOLF STEINER: Much of what you have said is good, but it would also be good in the course of your description to acquaint your students with the different parts of a single plant, because you will continually have to speak about the parts of the plant—leaf, blossom, and so on. It would therefore be good for the pupil to get to know certain parts of a plant, always following the principle that you have rightly chosen—that is, the study of the plant in relation to Sun and Earth. That will bring some life to your study of the plants; from there you should build the bridge to human beings. You have not yet succeeded in making this connection, because everything you said was more or less utilitarian—how plants are useful to people, for example—and other external comparisons. There is something else that must be worked out before these lessons can be of real value to the children; after you have made clear the connection between animal and human being, you must also try to show the connection between plant and human being. Most of the children are in their eleventh year when we begin this subject, and at this point the time is ripe to consider what the children have already learned—or rather, we must keep in mind that the children have already learned things in a certain way, which they must now put to good use. Then too you must not forget to give the children the kind of image of the plant’s actual form that they can understand. Comment: The germinating process should be demonstrated to the children—for example, in the bean. First the bean as a seed and then an embryo in its different stages. We could show the children how the plant changes through the various seasons of the year. RUDOLF STEINER: This should not really be given to your students until they are fifteen or sixteen years old. If you did take it earlier you would see for yourself that the children who are still in the lower grades cannot yet fully understand the germinating process. It would be premature to develop this germinating process with younger children—your example of the bean and so on. That is foreign to the child’s inner nature. I only meant to point out to the children the similarity between the young plant and the young animal, and the differences as well. The animal is cared for by its mother, and the plant comes into the world alone. My idea was to treat the subject in a way that would appeal more to the feelings. RUDOLF STEINER: Even so, this kind of presentation is not suitable for children; you would find that they could not understand it. Question: Can one compare the different parts of the plant with a human being? The root with the head, for example? RUDOLF STEINER: As Mr. T. correctly described, you must give plants their place in nature as a whole—Sun, Earth, and so on—and always remember to speak of them in relation to the universe. Then when you give the proper form to your lesson you will find that the children meet what you present with a certain understanding. Someone described how plants and human beings can be compared—a tree with a person, for example: human trunk = tree trunk; arms and fingers = branches and twigs; head = root. When a person eats, the food goes from above downward, whereas in a tree the nourishment goes from below upward. There is also a difference: whereas people and animals can move around freely and feel pleasure and pain, plants cannot do this. Each type of plant corresponds to some human characteristic, but only externally. An oak is proud, while lichens and mosses are modest and retiring.  RUDOLF STEINER: There is much in what you say, but no one has tried to give the children an understanding of the plant itself in its various forms. What would it be like if, for example, you perhaps ask, “Haven’t you ever been for a walk during the summer and seen flowers growing in the fields, and parts of them fly away when you blow on them? They have little ‘fans’ that fly away. And you have probably seen these same flowers a little earlier, when summer was not quite so near; then you saw only the yellow leaf shapes at the top of the stem; and even earlier, in the spring, there were only green leaves with sharp jagged edges. But remember, what we see at these three different times is all exactly the same plant! Except that, to begin with, it is mainly a green leaf; later on it is mainly blossom; and still later it is primarily fruit. Those are only the fruits that fly around. And the whole is a dandelion! First it has leaves—green ones; then it presents its blossoms, and after that, it gets its fruit. “How does all this happen? How does it happen that this dandelion, which you all know, shows itself at one time with nothing but green leaves, another time with flowers, and later with tiny fruits? “This is how it comes about. When the green leaves grow out of the earth it is not yet the hot part of the year. Warmth does not yet have as much effect. But what is around the green leaves? You know what it is. It is something you only notice when the wind passes by, but it is always there, around you: the air. You know about that because we have already talked about it. It is mainly the air that makes the green leaves sprout, and then, when the air has more warmth in it, when it is hotter, the leaves no longer remain as leaves; the leaves at the top of the stem turn into flowers. But the warmth does not just go to the plant; it also goes down into the earth and then back again. I’m sure that at one time or another you have seen a little piece of tin lying on the ground, and have noticed that the tin first receives the warmth from the Sun and then radiates it out again. That is really what every object does. And so it is also with warmth. When it is streaming downward, before the soil itself has become very warm, it forms the blossom. And when the warmth radiates back again from the earth up to the plant, it is working more to form the fruit. And so the fruit must wait until the autumn.” This is how you should introduce the organs of the plant, at the same time relating these organs to the conditions of air and heat. You can now go further, and try to elaborate the thoughts that were touched on when we began today, showing the plants in relation to the outer elements. In this way you can also connect morphology, the aspect of the plant’s form, with the external world. Try this. Someone spoke about plant-teaching. RUDOLF STEINER: Some of the thoughts you have expressed are excellent, but your primary goal must be to give the children a comprehensive picture of the plant world as a whole: first the lower plants, then those in between, and finally the higher plants. Cut out all the scientific facts and give them a pictorial survey, because this can be tremendously significant in your teaching, and such a method can very well be worked out concerning the plant world. Several teachers spoke at length on this subject. One of them remarked that “the root serves to feed the plant.” RUDOLF STEINER: You should avoid the term serves. It’s not that the root “serves” the plant, but that the root is related to the watery life of earth, with the life of juices. It is however not what the plant draws out of the ground that makes up its main nourishment, but rather the carbon from the air. Children cannot have a direct perception of a metamorphosis theory, but they can understand the relationship between water and root, air and leaves, warmth and blossoms. It is not good to speak about the plants’ fertilization process too soon—at any rate, not at the age when you begin to teach botany—because children do not yet have a real understanding of the fertilization process. You can describe it, but you’ll find that they do not understand it inwardly. Related to this is the fact that fertilization in plants does not play as prominent a part as generally assumed in our modernday, abstract, scientific age. You should read Goethe’s beautiful essays, written in the 1820s, where he speaks of pollination and so on. There he defends the theory of metamorphosis over the actual process of fertilization, and strongly protests the way people consider it so terribly important to describe a meadow as a perpetual, continuous “bridal bed!” Goethe strongly disapproved of giving such a prominent place to this process in plants. Metamorphosis was far more important to him than the matter of fertilization. In our present age it is impossible to share Goethe’s belief that fertilization is of secondary importance, and that the plant grows primarily on its own through metamorphosis; even though, according to modern advanced knowledge, you must accept the importance of the fertilization process, it still remains true, however, that we are doing the wrong thing when we give it the prominence that is customary today. We must allow it to retire more into the background, and in its place we must talk about the relationship between the plant and the surrounding world. It is far more important to describe the way air, heat, light, and water work on the plant, than to dwell on the abstract fertilization process, which is so prominent today. I want to really emphasize this; and because this is a very serious matter and particularly important, I would like you to cross this Rubicon, to delve further into the matter, so that you find the proper method of dealing with plants and the right way to teach children about them. Please note that it is easy enough to ask what similarities there are between animal and humankind; you will discover this from many and diverse aspects. But when you look for similarities between plants and humankind, this external method of comparison quickly falls apart. But let’s ask ourselves: Are we perhaps on the wrong path in looking for relationships of this kind at all? Mr. R. came closest to where we should begin, but he only touched on it, and he did not work it out any further. We can now begin with something you yourselves know, but you cannot teach this to a young child. Before we meet again, however, perhaps you can think about how to clothe, in language suited to children, things you know very well yourselves in a more theoretical way. We cannot just take human beings as we see them in life and compare them with the plant; nevertheless there are certain resemblances. Yesterday I tried to draw the human trunk as a kind of imperfect sphere.2 The other part that belongs to it—which you would get if you completed the sphere—indeed has a certain likeness to the plant when you consider the mutual relationship between plants and human beings. You could even go further and say that if you were to “stuff ” a person (forgive the comparison—you will find the right way of changing it for children) especially in relation to the middle senses, the sense of warmth, the sense of sight, the sense of taste, the sense of smell, then you would get all kinds of plant forms.3 If you simply “stuffed” some soft substance into the human being, it would assume plant forms. The plant world, in a certain sense, is a kind of “negative” of the human being; it is the complement. In other words, when you fall asleep everything related to your soul passes out of your body; these soul elements (the I and the actual soul) reenter your body when you awaken. You cannot very well compare the plant world with the body that remains lying in your bed; but you can truthfully compare it with the soul itself, which passes in and out. And when you walk through fields or meadows and see plants in all the brightness and radiance of their blossoms, you can certainly ask yourselves: What temperament is revealed here? It is a fiery temperament! The exuberant forces that come to meet you from flowers can be compared to qualities of soul. Or perhaps you walk through the woods and see mushrooms or fungi and ask: What temperament is revealed here? Why are they not growing in the sunlight? These are the phlegmatics, these mushrooms and fungi. So you see, when you begin to consider the human element of soul, you find relationships with the plant world everywhere, and you must try to work out and develop these things further. You could compare the animal world to the human body, but the plant world can be compared more to the soul, to the part of a human being that enters and “fills out” a person when awaking in the morning. If we could “cast” these soul forms we would have the forms of the plants before us. Moreover, if you could succeed in preserving a person like a mummy, leaving spaces empty by removing all the paths of the blood vessels and nerves, and pouring into these spaces some very soft substance, then you would get all kinds of forms from these hollow shapes in the human body. The plant world is related to human beings as I have just shown, and you must try to make it clear to the children that the roots are more closely related to human thoughts, and the flowers more related to feelings—even to passions and emotions. And so it happens that the most perfect plants—the higher, flowering plants—have the least animal nature within them; the mushrooms and the lowest types of plant are most closely akin to animals, and it is particularly these plants that can be compared least to the human soul. You can now develop this idea of beginning with the soul element and looking for the characteristics of the plants, and you can extend it to all the varieties of the plant world. You can characterize the plants by saying that some develop more of the fruit nature—the mushrooms, for example—and others more of the leaf nature, such as ferns and the lower plants, and the palms, too, with their gigantic leaves. These organs, however, are developed differently. A cactus is a cactus because of the rampant growth of its leaves; its blossom and fruit are merely interspersed among the luxuriant leaves. Try now to translate the thought I indicated to you into language suited for children. Exert your fantasy so that by next time you can give us a vivid description of the plant world all over the Earth, showing it as something that shoots forth into herb and flower, like the soul of the Earth, the visible soul, the soul made manifest. And show how the different regions of Earth—the warm zone, the temperate zone, and the cold zone—each has its prevailing vegetation, just as in a human being each of the various spheres of the senses within the soul make a contribution. Try to make it clear to yourself how one whole sphere of vegetation can be compared with the world of sound that a person receives into the soul, another with the world of light, yet another with the world of smell, and so on.Then try to bring some fruitful thoughts about how to distinguish between annuals and perennials, or between the flora of western, central, and eastern European countries. Another fruitful thought that you could come to is about how the whole Earth is actually asleep in summer and awake in winter. You see, when you work in this way you awaken in the child a real feeling for intimacy of soul and for the truth of the spirit. Later, when the children are grown, they will much more easily understand how senseless it is to believe that human existence, as far as the soul is concerned, ceases every evening and begins again each morning. Thus they will see, when you have shown them, that the relationship between the human body and soul can be compared to the interrelationship between the human world and the plant world. How then does the Earth affect the plant? Just as the human body works, so when you come to the plant world you have to compare the human body with the Earth—and with something else, as you will discover for yourselves. I only wanted to give you certain suggestions so that you, yourselves, using all your best powers of invention, can discover even more before next time. You will then see that you greatly benefit the children when you do not give them external comparisons, but those belonging to the inner life.

|

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Ten

01 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| In the latter case the children can tackle the study of scientific botanical systems with a truly human understanding. The plant realm is the soul world of the Earth made visible. The carnation is a flirt. |

| They unfold right under the Earth’s surface; they are there within the Earth and develop the Earth’s soul life. This was known to the people of ancient times, and that was why they placed Christmas—the time when we look for soul life—not in the summer, but during winter. |

| In this way you gradually form a view of life lived under the Earth during winter. That is the truth. And it is good to tell the children these things. This is something that even materialists could not argue with or consider an extravagant flight of fancy. |

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Ten

01 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Speech Exercises:

RUDOLF STEINER: The “ch” should be sounded in a thoroughly active way, like a gymnastic exercise.1 The following is a piece in which you have to pay attention both to the form and the content. From “Galgenlieder” by Christian Morgenstern: