| 74. The Redemption of Thinking (1956): Lecture III

24 May 1920, Dornach Translated by Alan P. Shepherd, Mildred Robertson Nicoll Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| I believe that someone who studies Kant really can understand him in such a way, as I tried to understand him in my booklet Truth and Science. Kant faces no question of the contents of the worldview with might and main in the end of the sixties and in the beginning of the seventies years of the eighteenth century, not anything that would have appeared in certain figures, pictures, concepts, ideas of the things with him, but he faces the formal question of knowledge: how do we get certainty of something in the outside world, of any existence in the outside world? |

| One has already to say, the things, considered according to truth, appear absolutely different than they present themselves to the history of philosophy under the influence of an unconscious nominalistic worldview which goes back largely to Kant and the modern physiology. |

| Snakes slough their skins. As well as the opponents understand skinning today, it is indeed a lie. Since I have shown today how you can find the philosophically conscientious groundwork of spiritual science in my first writings. |

| 74. The Redemption of Thinking (1956): Lecture III

24 May 1920, Dornach Translated by Alan P. Shepherd, Mildred Robertson Nicoll Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

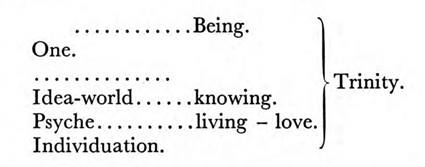

Yesterday at the end of the considerations about High Scholasticism, I attempted to point out that the most essential of a current of thought are problems that made themselves known in a particular way in the human being. They culminated in a certain yearning to understand: how does the human being attain that knowledge which is necessary for life, and how does this knowledge fit into that which controlled the minds in those days in social respect, how the knowledge does fit into the religious contents of the western church? The scholastics were concerned with the human individuality at first who was no longer able to carry up the intellectual life to concrete spiritual contents, as it still shone from that which had remained from Neo-Platonism, from the Areopagite and Scotus Eriugena. I have also already pointed to the fact that the impulses of High Scholasticism lived on in a way. However, they lived on in such a way that one may say, the problems themselves are big and immense, and the way in which one put them had a lasting effect. These should be just the contents of the today's consideration—the biggest problem, the relationship of the human being to the sensory and the spiritual realities, still continues to have an effect even if in quite changed methodical form and even if one does not note it, even if it has apparently taken on a quite different form. All that is still in the intellectual activities of the present, but substantially transformed by that which significant personalities have contributed to the European development in the philosophical area in the meantime. We also realise if we consider the Franciscan Monk Duns Scotus (~1266-1308) who taught in the beginning of the fourteenth century in Paris, later in Cologne, that as it were the problem becomes too big even for the excellent intellectual technique of scholasticism. Duns Scotus feels confronted with the question: how does the human soul live in the human-body? Thomas Aquinas still imagined that the soul worked on the totality of the bodily. So that the human being is only equipped indeed, if he enters into the physical-sensory existence, by the physical-bodily heredity with the vegetative forces, with the mineral forces and with the forces of sensory perceptivity that, however, without pre-existence the real intellect integrates into the human being which Aristotle called nous poietikos. This nous poietikos now soaks up as it were the whole mental—the vegetative mental, the animal mental—and intersperses the corporeality only to transform it in its sense in order to live on then immortal with that which it has obtained—after it had entered into the human body from eternal heights but without pre-existence—from this human body. Duns Scotus cannot imagine that the active intellect soaks up the entire human system of forces. He can only imagine that the human corporeality is something finished that in a certain independent way the vegetative and animal principles remain the entire life through, then it is taken off at death and that only the actually spiritual principle, the intellectus agens, goes over to immortality. Scotus cannot imagine like Thomas Aquinas that the whole body is interspersed with soul and spirit because to him the human mind had become something abstract, something that did no longer represent the spiritual world to him but that seemed to him to be gained only from consideration, from sense perception. He could no longer imagine that only in the universals, in the ideas that would be given which would prove reality. He became addicted to nominalism—as later his follower Ockham (William of O., ~1288-1347) did—to the view that ideas, as general concepts in the human being are only conceived from the sensory environment that it is, actually, only something that lives as names, as words in the human mind, I would like to say, for the sake of comfortable subsumption of existence. Briefly, he returned to nominalism. This is a significant fact, because one realises that nominalism, as it appeared, for example, with Roscelin of Compiègne—to whom even the Trinity disintegrated because of his nominalism-, is only interrupted by the intensive work of thought of Albert the Great and Thomas Aquinas and some others. Then the European humanity falls again back into nominalism which is incapable to grasp that which it has as ideas as spiritual reality, as something that lives in the human being and in a way in the things. The ideas become from realities straight away again names, mere empty abstractions. One realises which difficulties the European thinking had more and more if it put the question of knowledge. Since we human beings have to get knowledge from ideas—at least in the beginning of cognition. The big question has to arise repeatedly: how do the ideas provide reality? However, there is no possibility of an answer if the ideas appear only as names without reality. The ideas that were the last manifestations of a real spiritual world coming down from above to the ancient initiated Greeks became more and more abstract. We realise this process of abstracting, of equating the ideas with words increasing more and more if we pursue the development of western thinking. Single personalities outstand later, as for example Leibniz (Gottfried Wilhelm L., 1646-1716) who does not get involved in the question, how does one recognise by ideas, because he is quite traditionally still in the possession of a certain spiritual view and leads everything back to individual monads which are actually spiritual. Leibniz towers above the others, while he still has the courage to imagine the world as spiritual. Yes, the world is spiritual to him; it consists of nothing but spiritual beings. However, I would like to say what was to former times differentiated spiritual individualities are to Leibniz more or less gradually differentiated spiritual points, monads. The spiritual individuality is confirmed, but it is confirmed only in the form of the monad, in the form of a spiritual punctiform being. If we disregard Leibniz, we see, indeed, a strong struggle for certainty of the primal grounds of existence, but the incapacity everywhere at the same time to solve the nominalism problem. This becomes obvious with the thinker who is put rightly at the starting point of modern philosophy, Descartes (1596-1650) who lived in the beginning or in the first half of the seventeenth century. Everywhere in the history of philosophy one gets to know the real cornerstone of his philosophy with the proposition: cogito ergo sum, I think, therefore, I am.—One can note something of Augustine's pursuit in this proposition. Since Augustine struggles from that doubt of which I have spoken in the first talk, while he says to himself, I can doubt everything, but, the fact of doubting exists, and, nevertheless, I live, while I doubt. I can doubt that sensory things are round me, I can doubt that God exists that clouds are there that stars are there, but if I doubt, the doubt is there. I cannot doubt that which goes forward in my own soul. One can grasp a sure starting point there.—Descartes resumes this thought, I think, therefore, I am. Of course, with such things you expose yourself to serious misunderstandings if you are compelled to put something simple against something historically respected. It is still necessary. Descartes and many of his successors have in mind: if I have mental contents in my consciousness if I think, then one cannot deny the fact that I think; therefore, I am, therefore, my being is confirmed with my thinking. I am rooted as it were in the world being, while I have confirmed my being with my thinking. The modern philosophy begins with it as intellectualism, as rationalism that completely wants to work from the thinking and is in this respect only the echo of scholasticism. One realises two things with Descartes. First, one has to make a simple objection to him: do I understand my being because I think? Every night sleep proves the opposite.—This is just that simple objection which one has to make: we know every morning when we wake, we have existed from the evening up to the morning, but we have not thought. Thus, the proposition, I think, therefore, I am, is simply disproved. One has to make this simple objection, which is like the egg of Columbus, to a respected proposition that has found many supporters. However, the second question is, at which does Descartes aim philosophically? He aims no longer at vision, he aims no longer at receiving a world secret for the consciousness, and he is oriented in intellectualistic way. He asks, how do I attain certainty? How do I come out of doubt? How do I find out that things exist and that I myself exist?—It is no longer a material question, a question of the content-related result of world observation; it is a question of confirming knowledge. This question arises from the nominalism of the scholastics, which only Albert and Thomas had overcome for some time, which reappears after them straight away. Thus, that presents itself to the people which they have in their souls and to which they can attribute a name only to find a point somewhere in the soul from which they can get no worldview but the certainty that not everything is illusion, that they look at the world and look at something real, that they look into the soul and look at reality. In all that one can clearly perceive that to which I have pointed yesterday at the end, namely that the human individuality got to intellectualism, but did not yet feel the Christ problem in intellectualism. The Christ problem possibly appears to Augustine, while he still looks at the whole humanity. Christ dawns, I would like to say, in the Christian mystics of the Middle Ages; but He does not dawn with those who wanted to find Him with thinking only which is so necessary to the developing individuality, or with that which would arise to this thinking. This thinking appears in its original state in such a way that it emerges from the human soul that it rejects that which should just be the Christian or the core of the human being. It rejects the inner metamorphosis; it refuses to position itself to the cognitive life so that one would say to himself, yes, I think, I think about the world and myself at first. However, this thinking is not yet developed. This is the thinking after the Fall of Man. It has to tower above itself. It has to change; it has to raise itself into a higher sphere. Actually, this necessity appeared only once clearly in a thinker, in Spinoza (Benedictus Baruch S., 1632-1677), the successor of Descartes. With good reason, Spinoza made a deep impression on persons like Herder and Goethe. Since Spinoza understands this intellectualism in such a way that the human being gets finally to truth—which exists for Spinoza in a kind of intuition, while he changes the intellectual, does not stop at that which is there in the everyday life and in the usual scientific life. Spinoza just says to himself, by the development of thinking this thinking fills up again with spiritual contents.—We got to know in Plotinism, the spiritual world arises again to the thinking as it were if this thinking strives for the spirit. The spirit fulfils as intuition our thinking again. It is very interesting that just Spinoza says, we survey the world existence as it advances in spirit in its highest substance while we take up this spirit in the soul, while we rise with our thinking to intuition, while we are so intellectualistic on one side that we prove as one proves mathematically, but develop in proving at the same time and rise, so that the spirit can meet us.— If we rise in such a way, we also understand from this viewpoint the historical development of that what is contained in the development of humanity. It is strange to find the following sentence with a Jew, Spinoza, the highest revelation of the divine substance is given in Christ.—In Christ the intuition has become theophany, the incarnation of God, hence, Christ's voice is God's voice and the way of salvation.—The Jew Spinoza thinks that the human being can develop from his intellectualism in such a way that the spirit is coming up to meet him. If he can then turn to the Mystery of Golgotha, the fulfilment with spirit becomes not only intuition, that is appearance of the spirit by thinking, but it changes intuition into theophany, into the appearance of God himself. The human being faces God spiritually. One would like to say, Spinoza did not withhold that what he had suddenly realised, because this quotation proves that. It fulfils like a mood what he found out from the development of humanity this way; it fulfils his Ethics. Again, it devolves upon a receptive person. Therefore, one can realise that for somebody like Goethe who could read most certainly between the lines of the Ethics this book became principal. Nevertheless, these things do not want to be considered only in the abstract as one does normally in the history of philosophy; they want to be considered from the human viewpoint, and one must already look at that which shines from Spinozism into Goethe's soul. However, that which shines there only between the lines of Spinoza is something that did not become time dominating in the end but the incapacity to get beyond nominalism. Nominalism develops at first in such a way that one would like to say, the human being becomes more and more entangled in the thought: I live in something that cannot grasp the outside world, in something that is not able to go out from me to delve into the outside world and to take up something of the nature of the outside world.—That is why this mood that one is so alone in himself that one cannot get beyond himself and does not receive anything from the outside world appears already with Locke (John L., 1612-1704) in the seventeenth century. He says, what we perceive as colours, as tones in the outside world is no longer anything that leads us to the reality of the outside world; it is only the effect of the outside world on our senses, it is something with which we are entangled also in our own subjectivity.—This is one side of the matter. The other side of the matter is that with such spirits like Francis Bacon (1561-1626) nominalism becomes a quite pervasive worldview in the sixteenth, seventeenth centuries. For he says, one has to do away with the superstition that one considers that as reality which is only a name. There is reality only if we look out at the sensory world. The senses only deliver realities in the empiric knowledge.—Beside these realities, those realities do no longer play a scientific role for whose sake Albert and Thomas had designed their epistemology. The spiritual world had vanished to Bacon and changed into something that cannot emerge with scientific certainty from the inside of the human being. Only religious contents become that what is a spiritual world, which one should not touch with knowledge. Against it, one should attain knowledge only from outer observation and experiments. That continues this way up to Hume (David H., 1711-1776) in the eighteenth century to whom even the coherence of cause and effect is something that exists only in the human subjectivity that the human being adds only to the things habitually. One realises that nominalism, the heritage of scholasticism, presses like a nightmare on the human beings. The most important sign of this development is that scholasticism with its astuteness stands there that it originates in a time when that which is accessible to the intellect should be separated from the truths of a spiritual world. The scholastic had the task on one side to look at the truths of a spiritual world, which the religious contents deliver of course, the revelation contents of the church. On the other side, he had to look at that which can arise by own strength from human knowledge. The viewpoint of the scholastics missed changing that border which the time evolution would simply have necessitated. When Thomas and Albert had to develop their philosophy, there was still no scientific worldview. Galilei, Giordano Bruno, Copernicus, and Kepler had not yet worked; the intellectual view of the human being at the outer nature did not yet exist. There one did not have to deal with that which the human intellect can find from the depths of his soul, and which one gains from the outer sensory world. There one had to deal with that only which one has to find with the intellect from the depths of the soul in relation to the spiritual truths that the church had delivered, as they faced the human beings who could no longer rise by inner spiritual development to the real wisdoms who, however, realised them in the figure that the church had delivered, just simply as tradition, as contents of the scriptures and so on. Does there not arise the question: how do the intellectual contents relate—that which Albert and Thomas had developed as epistemology—to the contents of the scientific worldview? One would like to say, this is an unconscious struggle up to the nineteenth century. There we realise something very strange. We look back at the thirteenth century and see Albert and Thomas teaching humanity about the borders of intellectual knowledge compared with faith, with the contents of revelation. They show one by one: the contents of revelation are there, but they arise only up to a certain part of the human intellectual knowledge, they remain beyond this intellectual knowledge, there remains a world riddle to this knowledge.—We can enumerate these world riddles: the incarnation, the existence of the spirit in the sacrament of the altar and so on—they are beyond the border of human cognition. For Albert and Thomas it is in such a way that the human being is on the one side, the border of knowledge surrounds him as it were and he cannot behold into the spiritual world. This arises to the thirteenth century. Now we look at the nineteenth century. There we see a strange fact, too: during the seventies, at a famous meeting of naturalists in Leipzig, Emil Du Bois-Reymond (1818-1896) holds his impressive speech On the Borders of the Knowledge of Nature and shortly after about the Seven World Riddles. What has become there the question? (Steiner draws.) There is the human being, there is the border of knowledge; however, the material world is beyond this border, there are the atoms, there is that about which Du Bois-Reymond says, one does not know that which haunts as matter in space.—On this side of the border is that which develops in the human soul. Even if—compared to the imposing work of scholasticism—it is a trifle which faces us there, nevertheless, it is the true counterpart: there the question of the riddles of the spiritual world, here the question of the riddles of the material world; here the border between the human being and the atoms, there the border between the human being and the angels and God. We have to look into this period if we want to recognise what scholasticism entailed. There Kant's philosophy emerges, influenced by Hume, which influences the philosophers even today. After Kant's philosophy had taken a backseat, the German philosophers took the slogan in the sixties, back to Kant! Since that time an incalculable Kant literature was published, also numerous independent Kantian thinkers like Johannes Volkelt (1848-1930) and Hermann Cohen (1842-1918) appeared. Of course, we can characterise Kant only sketchily today. We want only to point to the essentials. I believe that someone who studies Kant really can understand him in such a way, as I tried to understand him in my booklet Truth and Science. Kant faces no question of the contents of the worldview with might and main in the end of the sixties and in the beginning of the seventies years of the eighteenth century, not anything that would have appeared in certain figures, pictures, concepts, ideas of the things with him, but he faces the formal question of knowledge: how do we get certainty of something in the outside world, of any existence in the outside world?—The question of certainty of knowledge torments Kant more than any contents of knowledge. I mean, one should even feel this if one deals with Kant's Critique that these are not the contents of knowledge, but that Kant strives for a principle of the certainty of knowledge. Nevertheless, read the Critique of Pure Reason, the Critique of Practical Reason, and realise—after the classical chapter about space and time—how he deals with the categories, one would like to say how he enumerates them purely pedantically in order to get a certain completeness. Really, the Critique of Pure Reason does not proceed in such a way, as with somebody who writes from sentence to sentence with lifeblood. To Kant the question is more important how the concepts relate to an outer reality than the contents of knowledge themselves. He pieces the contents together, so to speak, from everything that is delivered to him philosophically. He schematises, he systematises. However, everywhere the question appears, how does one get to such certainty, as it exists in mathematics? He gets to such certainty in a way which is strictly speaking nothing but a transformed and on top of that exceptionally concealed and disguised nominalism, which he expands also to the sensory forms, to space and time except the ideas, the universals. He says, that which we develop in our soul as contents of knowledge does not deal at all with something that we get out of the things. We put it on the things. We get out the whole form of our knowledge from ourselves. If we say, A is connected with B after the principle of causation, this principle of causation is only in us. We put it on A and B, on both contents of experience. We bring the causality into the things. With other words, as paradox this sounds, nevertheless, one has to say of these paradoxes, Kant searches a principle of certainty while he generally denies that we take the contents of our knowledge from the things, and states that we take them from ourselves and put them into the things. That is in other words, and this is just the paradox: we have truth because we ourselves make it; we have truth in the subject because we ourselves produce it. We bring truth only into the things. There you have the last consequence of nominalism. Scholasticism struggled with the universals, with the question: how does that live outdoors in the world what we take up in the ideas? It could not really solve the problem that would have become provisionally completely satisfactory. Kant says, well, the ideas are mere names, nomina. We form them only in ourselves, but we put them as names on the things; thereby they become reality. They may not be reality for long, but while I confront the things, I put the nomina into experience and make them realities, because experience must be in such a way as I dictate it with the nomina. Kantianism is in a way the extreme point of nominalism, in a way the extreme decline of western philosophy, the complete bankruptcy of the human being concerning his pursuit of truth, the desperation of getting truth anyhow from the things. Hence, the dictates: truth can only exist if we bring it into the things. Kant destroyed any objectivity, any possibility of the human being to submerge in the reality of the things. Kant destroyed any possible knowledge, any possible pursuit of truth, because truth cannot exist if it is created only in the subject. This is a consequence of scholasticism because it could not come into the other side where the other border arose which it had to overcome. Because the scientific age emerged and scholasticism did not carry out the volte-face to natural sciences, Kantianism appeared which took subjectivity as starting point and gave rise to the so-called postulates freedom, immortality, and the idea of God. We shall do the good, fulfil the categorical imperative, and then we must be able to do it. That is we must be free, but we are not able to do it, while we live here in the physical body. We reach perfection only, so that we can completely carry out the categorical imperative if we are beyond the body. That is why immortality must exist. However, we cannot yet realise that as human beings. A deity has to integrate that which is the contents of our action in the world—if we take pains of that what we have to do. That is why a deity must exist. Three religious postulates about which one cannot know how they are rooted in reality are that which Kant saved after his own remark: I had to remove knowledge to get place for faith.—Kant does not get place for religious contents in the sense of Thomas Aquinas, for traditional religious contents, but for abstract religious contents that just originate in the individual human being who dictates truth, that is appearance. With it, Kant becomes the executor of nominalism. He becomes the philosopher who denies the human being everything that this human being could have to submerge in any reality. Hence, Fichte, Schelling, and then Hegel immediately reacted against Kant. Thus, Fichte wanted to get everything that Kant had determined as an illusory world or as a world of appearances from the real creative ego that he imagined, however, to be rooted in the being of the world. Fichte was urged to strive for a more intensive, to a more and more mystic experience of the soul to get beyond Kantianism. He could not believe at all that Kant meant that which is included in his Critiques. In the beginning, with a certain philosophical naivety he believed that he drew the last consequence of Kant's philosophy. If one did not draw these last consequences, Fichte thought, one would have to believe that the strangest chance would have pieced this philosophy together but not a humanely thinking head. All that is beyond that which approaches with the emerging natural sciences that appear like a reaction just in the middle of the nineteenth century that strictly speaking understand nothing of philosophy, which degenerated, hence, with many thinkers into crass materialism. Thus, we realise how philosophy develops in the last third of the nineteenth century. We see this philosophical pursuit completely arriving at nullity, and then we realise how—from everything possible that one attaches to Kantianism and the like—one attempts to understand the essentials of the world. The Goethean worldview which would have been so significant if one had grasped it, got completely lost, actually, as a worldview of the nineteenth century, with the exception of those spirits who followed Schelling, Hegel and Fichte. Since in this Goethean worldview the beginning of that is contained which must originate from Thomism, only with the volte-face to natural sciences. Thomas could state only in the abstract that the mental-spiritual really works into the last activities of the human organs. In abstract form, Thomas Aquinas expressed that everything that lives in the human body is directed by the mental and must be recognised by the mental. Goethe started with the volte-face and made the first ground with his Theory of Colours, which people do not at all understand, and with his “morphology.” However, the complete fulfilment of Goetheanism is given only if one has spiritual science that clarifies the scientific facts by its own efforts. Some weeks ago, I tried here to explain how our spiritual science could be a corrective of natural sciences, we say, concerning the function of the heart. The mechanical-materialist view considers the heart as a pump that pushes the blood through the human body. However, it is quite the contrary. The blood circulation is something living—embryology can prove that precisely -, and it is set in motion by the internally moved blood. The heart takes the blood activity into the entire human individuality. The activity of the heart is a result of the blood activity, not vice versa. Thus, one can show concerning the single organs of the body how the comprehension of the human being as a spiritual being only explains his material existence. One can do something real in a way that Thomism had in mind in abstract form that said there, the spiritual-mental penetrates everything bodily. This becomes concrete knowledge. The Thomistic philosophy lives on as spiritual science in our present. I would like to insert a personal experience here. When I spoke in the Viennese Goethe Association about the topic Goethe as Father of a New Aesthetics, there was a very sophisticated Cistercian among the listeners. I explained how one has to imagine Goethe's idea of art, and this Cistercian, Father Wilhelm Neumann (1837-1919), professor at the theological faculty of the Vienna University, said something strange, you can find the origins of your talk already with Thomas Aquinas.—Nevertheless, it was interesting to me to hear from him who was well versed in Thomism that he felt that in Thomism is a kind of origin of that which I had said about the consequence of the Goethean worldview concerning aesthetics. One has already to say, the things, considered according to truth, appear absolutely different than they present themselves to the history of philosophy under the influence of an unconscious nominalistic worldview which goes back largely to Kant and the modern physiology. Thus, you would find many a thing if you referred to spiritual science. Read in my book The Riddles of the Soul which appeared some years ago how I tried there to divide the human being on the basis of thirty-year studies into three systems; how one system of the human physical body is associated with sense-perception and thinking, how the rhythmical system, breathing and heart activity, is associated with feeling, how metabolism is associated with the will. Everywhere I attempted to find the spiritual-mental in its creating in the physical. That is, I took the volte-face to natural sciences seriously. One tries to penetrate into the area of natural existence after the age of natural sciences, as before the age of scholasticism—we have realised it with the Areopagite and with Plotinus—one penetrated from the human knowledge into the spiritual area. One takes the Christ principle seriously as one would have taken the Christ principle seriously if one had said, the human thinking can change, so that it can penetrate if it casts off the original sin of the limits of knowledge and if it rises up by thinking free of sensuousness to the spiritual world—after the volte-face. What manifests as nature can be penetrated as the veil of physical existence. One penetrates beyond the limits of knowledge which a dualism assumed, as well as the scholastics drew the line at the other side. One penetrates into this material world and discovers that it is, actually, the spiritual one that behind the veil of nature no material atoms are in truth but spiritual beings. This shows how one thinks progressively about a further development of Thomism. Look for the most important psychological thoughts of Albert and Thomas in their abstractness. However, they did not penetrate into the human-bodily, so that they said how the mind or the soul work on the organs, but they already pointed to the fact that one has to imagine the whole human body as the result of the spiritual-mental. The continuation of this thought is the work to pursue the spiritual-mental down to the details of the bodily. Neither philosophy nor natural sciences do this, only spiritual science will do it, which does not shy away from applying the great thoughts like those of High Scholasticism to the views of nature of our time. However, for that an engagement with Kantianism was inevitable if the thing should scientifically persist. I tried this engagement with Kantianism first in my writings Truth and Science and Epistemology of Goethe's Worldview and, in the end, in my Philosophy of Freedom. Only quite briefly, I would like to defer to the basic idea of these books. These writings take their starting point from the fact that one cannot directly find truth in the world of sense perception. One realises in a way in which nominalism takes hold in the human soul how it can accept the wrong consequence of Kantianism, but how Kant did not realise that which was taken seriously in these books. This is that a consideration of the world of perception leads—if one does it quite objectively and thoroughly—to the conclusion: the world of perception is not a whole, it is something that we make a reality. In what way did the difficulty of nominalism originate? Where did the whole Kantianism originate? Because one takes the world of perception, and then the soul life puts the world of ideas upon it. Now one has the view, as if this world of ideas should depict the outer perception. However, the world of ideas is inside. What does this inner world of ideas deal with that which is there outdoors? Kant could answer this question only, while he said, so we just put the world of perception on the world of ideas, so we get truth. The thing is not in such a way. The thing is that—if we look at perception impartially—it is not complete, everywhere it is not concluded. I tried to prove this strictly at first in my book Truth and Science, then in my book Philosophy of Freedom. The perception is everywhere in such a way that it appears as something incomplete. While we are born in the world, we split the world. The thing is that we have the world contents here (Steiner draws). While we place ourselves as human beings in the world, we separate the world contents into a world of perception that appears to us from the outside and into the world of ideas that appears to us inside of our soul. Someone who regards this separation as an absolute one who simply says, there is the world, there I am cannot get over with his world of ideas to the world of perception. However, the case is this: I look at the world of perception; everywhere it is not complete in itself, something is absent everywhere. However, I myself have come with my whole being from the world to which also the world of perception belongs. There I look into myself: what I see by myself is just that which the world of perception does not have. I have to unite that which separated in two parts by my own existence. I create reality. Because I am born, appearance comes into being while that which is one separates into perception and the world of ideas. Because I live, I bring together two currents of reality. In my cognitive experience, I work the way up into reality. I would never have got to a consciousness if I had not split off the world of ideas from the world of perception while entering into the world. However, I would never find the bridge to the world if I did not combine the world of ideas that I have split off again with that which is not reality without the world of ideas. Kant searches reality only in the outer perception and does not guess that the other half of reality is just in that which we carry in ourselves. We have taken that which we carry as world of ideas in ourselves only from the outer reality. Now we have solved the problem of nominalism, because we do not put space, time, and ideas, which would be mere names, upon the outer perception, but now we give back the perception what we had taken from it when we entered into the sensory existence. Thus, we have the relationship of the human being to the spiritual world at first in a purely philosophical form. Someone is just overcoming Kantianism who takes up this basic idea of my Philosophy of Freedom, which the title of the writing Truth and Science already expresses: the fact that real science combines perception and the world of ideas and regards this combining as a real process. However, he is just coping with the problem which nominalism had produced which faced the separation into perception and the world of ideas powerlessly. One approaches this problem of individuality in the ethical area. Therefore, my Philosophy of Freedom became a philosophy of reality. While cognition is not only a formal act but also a process of reality, the moral action presents itself as an outflow of that which the individual experiences as intuition by moral imagination. The ethical individualism originates this way as I have shown in the second part of my Philosophy of Freedom. This individualism is based on the Christ impulse, even if I have not explicitly said that in my Philosophy of Freedom. It is based on that which the human being gains to himself as freedom while he changes the usual thinking into that which I have called pure thinking in my Philosophy of Freedom which rises to the spiritual world and gets out the impulses of moral actions while something that is bound, otherwise, to the human physical body, the impulse of love, is spiritualised. While the moral ideals are borrowed from the spiritual world by moral imagination, they become the force of spiritual love. Hence, the Philosophy of Freedom had to counter Kant's philistine principle—“Duty! You elated name, you do not have anything of flattery with yourself but strict submission” -, with the transformed ego which develops up into the sphere of spirituality and starts there loving virtue, and, therefore, practises virtue because it loves it out of individuality. Thus, that which remained mere religious contents to Kant made itself out to be real world contents. Since to Kant knowledge is something formal, something real to the Philosophy of Freedom. A real process goes forward. Hence, the higher morality is also tied together with it to a reality, which philosophers of values like Windelband (Wilhelm, 1845-1915) and Rickert (Heinrich R., 1863-1936) do not at all reach. Since they do not find out for themselves how that which is morally valuable is rooted in the world. Of course, those people who do not regard the process of cognition as a real process do not get to rooting morality in the world of reality; they generally get to no philosophy of reality. From the philosophical development of western philosophy, spiritual science was got out, actually. Today I attempted to show that that Cistercian father heard not quite inaccurately that really the attempt is taken to put the realistic elements of High Scholasticism with spiritual science in our scientific age, how one was serious about the change of the human soul, about the fulfilment of the human soul with the Christ impulse also in the intellectual life. Knowledge is made a real factor in world evolution that takes place only on the scene of the human consciousness as I have explained in my book Goethe's Worldview. However, these events in the world further the world and us within the world at the same time. There the problem of knowledge takes on another form. That which we experience changes spiritual-mentally in ourselves into a real development factor. There we are that which arises from knowledge. As magnetism works on the arrangement of filings of iron, that works in us what is reflected in us as knowledge. At the same time, it works as our design principle, then we recognise the immortal, the everlasting in ourselves, and we do no longer raise the issue of knowledge in only formal way. The issue of knowledge was always raised referring to Kant in such a way that one said to himself, how does the human being get around to regarding the inner world as an image of the outer world?—However, cognition is not at all there at first to create images of the outer world but to develop us, and it is an ancillary process that we depict the outside world. We let that flow together in the outside world in an ancillary process, which we have split off at our birth. It is exactly the same way with the modern issue of knowledge, as if anybody has wheat and investigates its nutritional effect if he wants to investigate the growth principle of wheat. Indeed, one may become a food chemist, but food chemistry does not recognise that which is working from the ear through the root, the stalk, and the leaves to the blossom and fruit. It explains something only that is added to the normal development of the wheat plant. Thus, there is a developmental current of spiritual life in us, which is concerned with our being to some extent as the plant develops from the root through the stalk and leaves to the blossom and the fruit, and from there again to the seed and the root. As that which we eat should not play any role with the explanation of the plant growth, the question of the epistemological value of that which lives in us as a developmental impulse must also not be the basis of a theory of knowledge, but it has to be clear that knowledge is a side effect of the work of the ideal in our human nature. There we get to the real of that which is ideal. It works in us. The wrong nominalism, Kantianism, originated only because one put the question of knowledge in such a way as food chemistry would put the question of the nature of wheat. Hence, one may say, not before we find out for ourselves what Thomism can be for the present, we see it originating in spiritual science in its figure for the twentieth century, and then it is back again as spiritual science. Then light is thrown on the question: how does this appear if now one comes and says, compared with the present philosophy one has to go back to Thomas Aquinas, and to study him, at most with some critical explanations and something else that he wrote in the thirteenth century?—There we realise, what it means, to project our thoughts in honest and frank way in the development current that takes High Scholasticism as starting point, and what it means to carry back our mind to this thirteenth century surveying the entire European development since the thirteenth century. This resulted from the encyclical Aeterni patris of 1879 that asks the Catholic clerics to regard the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas as the official philosophy of the Catholic Church. I do not want to discuss the question here: where is Thomism? Since one would have to discuss the question: do I look best at the rose that I face there if I disregard the blossom and dig into the earth to look at the roots and check as to whether something has already originated from the root. Now, you yourselves can imagine all that. We experience what asserts itself among us as a renewal of that Thomism, as it existed in the thirteenth century, beside that which wants to take part honestly in the development of the European West. We may ask on the other hand, where does Thomism live in the present? You need only to put the question: how did Thomas Aquinas himself behave to the revelation contents? He tried to get a relationship to them. We have the necessity to get a relationship to the contents of physical manifestation. We cannot stop at dogmatics. One has to overcome the “dogma of experience” as on the other side one has to overcome the dogma of revelation. There we have really to make recourse to the world of ideas that receives the transforming Christ principle to find again our world of ideas, the spiritual world with Christ in us. Should the world of ideas remain separated? Should the world of ideas not participate in redemption? In the thirteenth century, one could not yet find the Christian principle of redemption in the world of ideas; therefore, one set it against the world of revelation. This must become the progress of humanity for the future that not only for the outer world the redemption principle is found, but also for the human intellect. The unreleased human reason only could not rise in the spiritual world. The released human intellect that has the real relationship to Christ penetrates into the spiritual world. From this viewpoint, Christianity of the twentieth century is penetrating into the spiritual world, so that it deeply penetrates into the thinking, into the soul life. This is no pantheism, this is Christianity taken seriously. Perhaps one may learn just from this consideration of the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas—even if it got lost in abstract areas—that spiritual science takes the problems of the West seriously that it always wants to stand on the ground of the present. I know how many false things arise now. I could also imagine that now again one says, yes, he has often changed his skin; he turns to Thomism now because the things become risky.—Indeed, one called the priests of certain confessions snakes in ancient times. Snakes slough their skins. As well as the opponents understand skinning today, it is indeed a lie. Since I have shown today how you can find the philosophically conscientious groundwork of spiritual science in my first writings. Now I may point to two facts. In 1908, I held a talk about the philosophical development of the West in Stuttgart. In this talk, I did not feel compelled to point to the fact that possibly my discussion of Thomism displeased the Catholic clerics, because I did justice to Thomism, I emphasised its merits even with much clearer words than the Neo-Thomists, Kleutgen or others did. Hence, I did not find out for myself in those days that my praise of Thomism could be taken amiss by the Catholic clergy, and I said, if one speaks of scholasticism disparagingly, one is not branded heretical by the so-called free spirits. However, if one speaks, objectively about that, one is easily misunderstood because one often rests philosophically upon a misunderstood Thomism within the positive and just the most intolerant church movement. I did not fear at all to be attacked because of my praise of Thomism by the Catholic clergy, but by the so-called free spirits. It happened different, and people will say, we are the first whom he did a mischief. During these days, I have also pointed to my books that I wrote around the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, among them also to a book that I dedicated to Ernst Haeckel, Worldviews and Approaches to Life in the Nineteenth Century. There I pointed to the fact that the modern thinking is not astute and logical; and that Neo-Scholasticism tried to rest upon the strictly logical of Thomism. I wrote: “These thinkers could really move in the world of ideas without imagining this world in unsubtle sensory-bodily form.” I spoke about the scholastics this way, and then I still spoke about the Catholic thinkers who had taken the study of scholasticism again: “The Catholic thinkers who try today to renew this art of thinking are absolutely worth to be considered in this respect. It will always have validity what one of them, the Jesuit father Joseph Kleutgen (1811-1889), says in his book An Apology of the Philosophy of the Past: “Two sentences form the basis of the different epistemologies which we have just repeated: the first one, that our reason ...” and so on. You realise, if the Jesuit Joseph Kleutgen did something meritorious, I acknowledged it in my book. However, this had the result that one said in those days that I myself was a disguised Jesuit. At that time, I was a disguised Jesuit; now you read in numerous writings, I am a Jew. I only wanted to mention this at the end. In any case, I do not believe that anybody can draw the conclusion from this consideration, that I have belittled Thomism. These considerations should show that the High Scholasticism of the thirteenth century was a climax of European intellectual development, and that the present time has reason to go into it. We can learn very much for deepening our thought life to overcome any nominalism, so that we find Christianity again by Christianising the ideas that penetrate into the spiritual being from which the human being must have originated, because only the consciousness of his spiritual origin can give him satisfaction. |

| 74. The Philosophy of Thomas Aquinas: Thomas and Augustine

22 May 1920, Dornach Translated by Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The whole personality and the whole struggle of Augustine can be understood only when one understands how much of the neoplatonic philosophy had entered into his soul; and if we study objectively the development of Augustine, we find that the break which occurred in going over from Manichaeism to Platonism was hardly as violent in the transition from Neoplatonism to Christianity. |

| Neither do we understand that wonderful genius who closes the circle of Greek philosophy, Aristotle, unless we know that whenever he speaks of concepts, he still keeps within the meaning of an experienced tradition which regarded concepts as belonging to the outer world of the senses as well as perceptions, though he is already getting close to the border of understanding abstract thought free from all evidence of the senses. |

| I might say, if I may express myself clearly: we understand the world through sense-observations which through abstraction we bring to concepts, and end there. |

| 74. The Philosophy of Thomas Aquinas: Thomas and Augustine

22 May 1920, Dornach Translated by Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|