| 147. Secrets of the Threshold: Lecture IV

27 Aug 1913, Munich Translated by Ruth Pusch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| I have continually said: The chapter of Schopenhauer's philosophy that views the world as a mere mental image and does not distinguish between idea and actual perception can be contradicted only by life itself. Kant's argument, too, in regard to the so-called proof of God' s existence, that a hundred imaginary dollars contain just as many pennies as a hundred real dollars, will be demolished by anyone who tries to pay his debts with imaginary and not real dollars. |

| 147. Secrets of the Threshold: Lecture IV

27 Aug 1913, Munich Translated by Ruth Pusch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

The soul, as it becomes clairvoyant, will progress further, beyond the elemental world we have been describing in these lectures, and it will penetrate the actual spiritual world. On ascending to this higher world, the soul must take into account even more forcefully what already has been indicated. In the elemental world there are many happenings and phenomena surrounding the clairvoyant soul that remind it of the characteristics, the forces, and of all sorts of other things in the sense world, but rising into the spiritual world, the soul finds the happenings and beings totally different. The capacities and points of view it could get on with in the sense world have to be given up to a far greater degree. It is terribly disturbing to confront a world that the soul is not at all accustomed to, leaving everything behind it has so far been able to experience and observe. Nevertheless, when you look into my books Theosophy or Occult Science or if you recall the recent performance of Scenes Five and Six of The Souls' Awakening, it will occur to you that the descriptions there of the real spiritual world, the scientific descriptions as well as the more pictorial-scenic ones, use pictures definitely taken—one can say—from impressions and observations of the physical sense world. Recall for a moment how the journey is described through Devachan or the Spirit-land, as I called it. You will find that the pictures used have the characteristics of sense perception. This is, of course, necessary if one proposes to put on the stage the spirit region, which the human being passes through between death and a new birth. All the happenings must be represented by images taken from the physical sense world. You can easily imagine that stage hands nowadays would not know what to do with the sort of scenery one might bring immediately out of the spiritual world, having nothing at all in common with the sense world. One therefore faces the necessity of describing the region of spirit with pictures taken from sense observation. But there is more to it than this. You might well believe that to represent this world whose characteristics are altogether different from the sense world, one has to help oneself out of the difficulty with sense-perceptible images. This is not the case. When the soul that has become clairvoyant enters the spiritual world, it will really see the landscape as the exact scenery of those two scenes of the “Spirit Region” in The Souls' Awakening. They are not just thought out in order to characterize something that is entirely different; the clairvoyant soul really is in such scenery and surrounded by it. Just as the soul surrounded in the physical sense world by a landscape of rocks, mountains, woods and fields must take these for granted as reality if it is healthy, the clairvoyant soul, too, outside the physical and etheric bodies can observe itself surrounded in exactly the same way by a landscape constructed of these pictures. Indeed, the pictures have not been chosen at random; as a matter of fact they are the actual environment of the soul in this world. Scenes Five and Six of The Souls' Awakening did not come about in just this way because something or other of an unknown world had to be expressed and therefore the question was considered, “How can that be done?” No, this world pictured here is the world surrounding the soul that it to some degree simply forms as an image. However, it is necessary for the clairvoyant soul to enter into the right relationship to the genuine reality of the spirit world, the spirit-land that has nothing at all in common with the sense world. You will get some idea of the relationship to the spiritual world which the soul has to acquire from a description of how the soul can come to an understanding of that world. Suppose you open a book. At the top of the page you find a line slanting from the left above to the right below, then a line slanting from bottom left to top right, another line parallel to the first and still another parallel to the second; then come two vertical lines, the second shorter than the first and connected at the top to its center. Then comes something like a circle that is not quite closed with a horizontal line in its center; finally come two equal vertical lines joined together at the top. You don't go through all this when you open a book and look at the first thing that stands there, do you? You read the word “when.” You do not describe the w as lines and the e as an incomplete circle, and so on; you read. When you look at the forms of the letters in front of you, you enter into a relationship with something that is not printed on the page; it is, however, indicated to you by what is there on that page. It is precisely the same with the relationship of the soul to the whole picture-world of the spirit region. What the soul has to do is not merely to describe what is there, for it is much more like reading. The pictures before one are indeed a cosmic writing, a script, and the soul will gain the right inner mood by recognizing that this whole world of pictures—woven like a veil before the spiritual world—is there to mediate, to manifest the true reality of that world. Hence in the real sense of the word we can speak of reading the cosmic script in the spirit region. One should not imagine that learning to read this cosmic writing is anything like learning to read in the physical world. Reading today is based more or less on the relation of arbitrary signs to their meaning. Learning to read as we have to do for such arbitrary letters is unnecessary for reading the cosmic script which makes its appearance as a mighty tableau, expressing the spiritual world to the clairvoyant soul. One has only to take in with an open, unbiased inner being what is shown as picture-scenery, because what one is experiencing there is truly reading. The meaning itself can be said to flow out of the pictures. It can therefore happen that any sort of interpreting the images of the spiritual world as abstract ideas is more a hindrance than a help in leading the soul directly to what lies behind the occult writing. Above all, as described in Theosophy and in the scenes of The Souls' Awakening, it is important to let the things work freely on one. With one's deep inner powers coming sometimes in a shadowy way to consciousness, there will already have been surmises of a spiritual world. To receive such hints, it is not even necessary to strive for clairvoyance—bear this well in mind. It is necessary only to keep one's mind and soul receptive to such pictures, without setting oneself against them in an insensitive, materialistic way, saying, “This is all nonsense; there are no such things!” A person with a receptive attitude who follows the movement of these pictures will learn to read them. Through the devotion of the soul to the pictures, the necessary understanding for the world of the spirit will come about. What I have described is actual fact—therefore the numerous objections to spiritual science coming from a present-day materialistic outlook. In general, these objections are first of all rather obvious; then, too, they can be very intelligent and apparently quite logical. Someone like Ferdinand Fox,11 who is considered so supremely clever not only by the human beings but also, quite correctly, by Ahriman himself, can say, “Oh yes, you Steiner, you describe the clairvoyant consciousness and talk about the spiritual world, but it's merely a collection of bits and pieces of sense images. How can you claim—in the face of all that scenery raked together from well-known physical pictures—that we should experience something new from it, something we cannot imagine without approaching the spiritual world?” That objection is one that will confuse many people; it is made from the standpoint of present-day consciousness apparently with a certain justification, indeed even with complete justification. Nevertheless when you go more deeply into such objections as these of Ferdinand Fox, you will discover the way to the truth: The objection we have just heard resembles very much what a person could say to someone opening a letter: “Well, yes, you've received a letter, but there's nothing in it but letters of the alphabet and words I already know. You won't hear anything new from all that!” Nevertheless, through what we have known for a long time we are perhaps able to learn something that we never could have dreamed of before. This is the case with the picture-scenery, which not only has to find its way to the stage for the Mystery Drama performance but also will reveal itself on every side to the clairvoyant consciousness. To some extent it is composed of memory pictures of the sense world, but in its appearance as cosmic script it represents something that the human being cannot experience either in the sense world or in the elemental world. It should be emphasized again and again that our relation to the spiritual world must be compared to reading and not to direct vision. If a man on earth, who has become clairvoyant, is to understand the objects and happenings of the sense world and look at them with a healthy, sane attitude, he must observe and describe them in the most accurate way possible, but his relation to the spiritual world must be different. As soon as he steps across the threshold, he has to do something very much like reading. If we look at what has to be recognized in this spirit land for our human life, there is certainly something else that can demolish Ferdinand Fox's argument. His objections should not be taken lightly, for if we wish to understand spiritual science in the right way, we should size up such objections correctly. We must remember that many people today cannot help making objections, for their ideas and habits of thought give them the dreadful fear of standing on the verge of nothingness when they hear about the spiritual world; therefore they reject it. This relationship of a modern human being to the spiritual world can be understood better by discovering what someone thinks about it who is quite well-intentioned. A book appeared recently that is worth reading even for those who have acquired a true understanding of the spiritual world. It was written by a man who means well and who would like very much to come by knowledge of the spiritual world, Maurice Maeterlinck;12 it has been translated with the title Concerning Death. In his first chapters the author shows that he wants to understand these things. We know that he is to some extent a discerning and sensitive person who has allowed himself to be influenced by Novalis, among others, that he has specialized somewhat in Romantic mysticism and that he has accomplished much that is very interesting—theoretically and artistically—in regard to the relationship of human beings to the super-sensible world. Therefore as example he is particularly interesting. Well, in the chapters of Concerning Death in which Maeterlinck speaks of the actual relationship of the human being to the spiritual world, his book becomes completely absurd. It is an interesting phenomenon that a well-meaning man, using the thinking habits of today, becomes foolish. I do not mean this as reproof or criticism but only to characterize objectively how foolish a well-intentioned person can become when he wishes to look at the connection of the human soul to the spirit world. Maurice Maeterlinck has not the slightest idea that there is a possibility to so strengthen and invigorate the human soul that it can shed everything attained through sense observation and the ordinary thinking, feeling and willing of the physical plane and indeed, even that of the elemental world. To such minds as Maeterlinck's, when the soul leaves behind it everything involved in sense observation and the thinking, feeling and willing related to it, there is simply nothing left. Therefore in his book Maeterlinck asks for proofs of the spiritual world and facts about it. It is of course reasonable to require proofs of the spiritual world and we have every right to do so—but not as Maeterlinck demands them. He would like to have proofs as palpable as those given by science for the physical plane. And because in the elemental world things are still reminiscent of the physical world, he would even agree to let himself be convinced of the existence of the spiritual world by means of experiments copied from the physical ones. That is what he demands. He shows with this that he has not the most rudimentary understanding of the true spiritual world, for he wants to prove, by methods borrowed from the physical one, things and processes which have nothing to do with the sense world. The real task is to show that such proofs as Maeterlinck demands for the spiritual world are impossible. I have frequently compared this demand of Maurice Maeterlinck to something that has taken place in the realm of mathematics. At one time the university Math departments were continually receiving treatises on the so-called squaring of the circle. People were constantly trying to prove geometrically how the area of a circle could be transformed into a square. Until quite recently an infinite number of papers had been written on the subject. But today only a rank amateur would still come up with such a treatise, for it has been proved conclusively that the geometrical squaring of the circle is not possible. What Maeterlinck demands as proof for the spiritual world is nothing but the squaring of the circle transferred to the spiritual sphere and is just as much out of place as the other is in the realm of mathematics. What actually is he demanding? If we know that as soon as we cross the threshold to the spiritual world, we are in a world that has nothing in common with the physical world or even with the elemental world, we cannot ask, “If you want to prove any of this to me, kindly go back into the physical world and with physical means prove to me the things of the spiritual world.” We might as well accept the fact that in everything concerned with spiritual science we will get from the most well-meaning people the kind of absurdities that—transferred to ordinary life—would at once show themselves to be absurd. It is just as if someone wants a man to stand on his head while continuing to walk with his feet. Let someone demand that and everyone will realize what nonsense it is. However, when someone demands the same sort of thing in regard to proofs of the spiritual world, it is clever; it is a scientific right. Its author will not notice its absurdity and neither will his followers, especially when the author is a celebrated person. The great mistake springs from the fact that those who make such claims have never clearly grasped man's relation to the spiritual world. If we attain concepts that can be gained only in the spiritual world through clairvoyant consciousness, they will naturally meet with a great deal of opposition from people like Ferdinand Fox. All the concepts that we are to acquire, for instance, about reincarnation, that is, the truly genuine remembrances of earlier lives on earth, we have to gain through a certain necessary attitude of the soul towards the spiritual world, for only out of that world can we obtain such concepts. When there are impressions, ideas, mental images in the soul that point back to an earlier life on earth, they will be especially subject to the antagonism of our time. Of course, it can't be denied that just in these things the worst foolishness is engaged in; many people have this or that experience and at once relate it to this or that former incarnation. In such cases it is easy for our opponents to say, “Oh yes, whatever drifts into your psyche are really pictures of experiences you've had in this life between birth and death—only you don't recognize them.” That is certainly the case hundreds and hundreds of times, but it should be clear that a spiritual investigator has an eye for these things. It can really be so that something that happens to a person in childhood or youth returns to consciousness completely transformed in later life; then perhaps because the person does not recognize it, he takes it for a reminiscence from an earlier life on earth. That can well be the case. We know within our own anthroposophical circles how easily it can occur. You see, memories can be formed not only of what one has clearly experienced; one can also have an impression that whisks past so quickly that it does not come fully to consciousness and yet can return later as a distinct memory. A person—if he is not sufficiently critical—can then swear that this is something in his soul that was never experienced in his present life. It is thus understandable that such impressions cause all the foolishness in people who have busied themselves, but not seriously enough, with spiritual science. This happens chiefly in the case of reincarnation, in which so much vanity and ambition is involved. For many people it is an alluring idea to have been Julius Caesar or Marie Antoinette in a former life. I can count as many as twenty-five or twenty-six Mary Magdalenes I have met in my lifetime! The spiritual investigator himself has good reason to draw attention to the mischief that can be stirred up in all this. Something more, however, must be emphasized. In true clairvoyance, impressions of an earlier life on earth will appear in a certain characteristic way, so that a truly healthy clairvoyant soul will recognize them quite definitely as what they are. It will know unmistakably that these impressions have nothing to do with what can arise out of the present life between birth and death. For the true reminiscences, the genuine memories of earlier lives on earth that come through scrupulous clairvoyance, are too astonishing for the soul to believe it could bring them out of its conscious or unconscious depths by any humanly possible method. Students of spiritual science must get to know what soul experiences come to it from outside. It is not only the wishes and desires, which do indeed play a great part when impressions are fished up out of the unknown waters of the soul in a changed form, so that we do not recognize them as experiences of the present life; there is an interplay of many other things. But the mostly overpowering perceptions of former earth lives are easy to distinguish from impressions out of the present life. To take one example: a person receiving a true impression of a former life will inwardly, for instance, experience the following, rising out of soul depths: “You were in your former life such and such a person.” And at the moment when this occurs, he will find that, externally, in the physical world, he can make no use at all of such knowledge. It can bring him further in his development but as a rule he has to say to himself, “Look at that: in your previous incarnation you had that special talent!” However, by the time he receives such an impression, he is already too old to do anything with it. The situation will always be like that, showing how the impressions could not possibly arise out of one's present life, for if you took your start from the ordinary dream or fantasy, you would provide yourself with quite different qualities in a former incarnation. What one was like in an earlier life is something we ordinarily cannot imagine, for it is usually just the opposite of what we might expect. The genuine reality of an impression arising through true clairvoyance may show in one way or another our relationship to another person on earth. However, we must remember that through incorrect clairvoyance many previous incarnations are described, relating us to our close friends and enemies; this is mostly nonsense. If the perception you receive is truly genuine, it will show you a relationship to a person whom it is impossible at the time to draw near to. These things cannot be applied directly to practical life. Confronted with impressions such as these, we have to develop the frame of mind necessary for clairvoyant consciousness. Naturally, when one has the impression, “I am connected in a special way with this person,” the situation must be worked out in life; through the impression one should come again into some sort of relationship with him. But that may only come about in a second or third earthly life. One must have a frame of mind able to wait patiently, a feeling that can be described as a truly inward calmness of soul and peacefulness of spirit. This will contribute to our judging correctly our experience in the spiritual world. When we want to learn something about another person in the physical world, we go at it in whatever way seems necessary. But this we cannot do with the impression that calls for spirit peacefulness, calmness of soul, and patience. The attitude of soul towards the genuine impressions of the spiritual world is correctly described by saying,

In a certain respect this frame of mind must stream out over the entire soul life in order to approach in the right way its clairvoyant experiences in the spirit. The Ferdinand Foxes, however, are not always easy to refute, even when inner perceptions arise of which one can say, “It is humanly not possible for the soul with its forces and habits acquired in the present earth life to create in the imagination what is rising out of its depths; on the contrary, if it were up to the soul it would have imagined something quite different.” Even when one is able to point out the sure sign of true, genuine, spiritual impressions, a super-clever Ferdinand Fox can come and raise objections. But one does not meet the objections of those who stand somewhat remote from the science of the spirit or of opponents who don't want to know anything about it with the words, “One's inner being filled with expectation.” This is the right mood for those who are approaching the spiritual world, but in the face of objections from opponents, one should not—as a spiritual scientist—merely wait in expectation but should oneself raise all those objections in order to know just what objections are possible. One of these is easy to understand today, and it can be found in all the psychological, psychopathological and physiological literature and in the sometimes learned treatises that presume to be scientific, as follows: “Since the inner life is so complicated, there is a great deal in the subconscious that does not rise up into the ordinary consciousness.” One who is super-clever will not only say, “Our wishes and desires bring all sorts of things out of soul depths,” but will also say, “Any experience of the psyche brings about a secret resistance or opposition against the experience. Though he will always experience this reaction, a person knows nothing of it as a rule. But it can push its way up from the subconscious into the upper regions of soul life.” Psychological, psychopathological and physiological literature admit to the following, because the facts cannot be denied: When someone falls deeply in love with another person, there has to develop in unconscious soul depths, side by side with the conscious love, a terrible antipathy to the beloved. And the view of many psychopathologists is that if anyone is truly in love, there is also hatred in his soul. Hatred is present even if it is covered over by the passion of love. When such things emerge from the depths of the soul, say the Ferdinand Foxes, they are perceptions that very easily provide the illusion of not coming from the soul of the individual involved and yet can well do so, because soul life is very complex. To this we can only reply: certainly it may be so; this is as well-known to the spiritual investigator as it is to the psychologist, psychiatrist or physiologist. When we work our way through all the above-mentioned literature dealing with the healthy and unhealthy conditions of soul life, we realize that Ferdinand Fox is a real person, an extremely important figure of the present day, to be found everywhere. He is no invention. Take all the abundant writing of our time and as you study it, you get the impression that the remarkable face of Ferdinand Fox is springing out at you from every page. He seems nowadays to have his fingers in every scientific pie. To counteract him, it must be emphasized again and again, and I repeat it in this case gladly: to prove that something is reality and not fantasy is only possible through life experience itself. I have continually said: The chapter of Schopenhauer's philosophy that views the world as a mere mental image and does not distinguish between idea and actual perception can be contradicted only by life itself. Kant's argument, too, in regard to the so-called proof of God' s existence, that a hundred imaginary dollars contain just as many pennies as a hundred real dollars, will be demolished by anyone who tries to pay his debts with imaginary and not real dollars. Therefore the training and devotion of the soul to clairvoyance must be taken as reality. It is not a matter of theorizing; we bring about a life in the realm of spirit by means of which we can clearly distinguish the genuine impression of a former life on earth from one that is false, in the same way that we can distinguish the heat of an iron on our skin from an imaginary iron. If we reflect on this, we will understand that Ferdinand Fox's objections about the spiritual world are really of no importance at all, coming as they do from people who—I will not say, have not entered the realm of spirit clairvoyantly—but who have never tried to understand it. We must always keep in mind that when we cross the threshold of the spiritual world, we enter a region of the universe that has nothing in common with what the senses can perceive or with what we experience in the physical world through willing, thinking, and feeling. We have to approach the spiritual world by realizing that all our ability to observe and understand the physical sense world has to be left behind. Referring to perception in the elemental world, I used an image that may sound grotesque, that of putting one's head into an ant hill—but so it is for our consciousness in the elemental world. There the thoughts that we have do not put up with everything quite passively; we plunge our consciousness into a world (into a thought-world, one might call it) that creeps and crawls with a life of its own. A person has to hold himself firmly upright in his soul to withstand thoughts that are full of their own motion. Even so, many things in this elemental world of creeping and crawling thoughts remind us of the physical world. When we enter the actual spiritual world, nothing at all reminds us of the physical world; there we enter a world which I will describe with an expression used in my book The Threshold of the Spiritual World: “a world of living thought-beings.” Our thinking in the physical world resembles shadow-pictures, shadows of thoughts, whose real substance we find in the spiritual world; this thought-substance forms the beings there whom we can approach and enter into. Just as human beings in the physical world consist of flesh and blood, these beings of the spiritual world consist of thought-substance. They are themselves thoughts, actual thoughts, nothing but thoughts, yet they are alive with an inner essential being; they are living thought-beings. Although we can enter into their inner being, they cannot perform actions as if with physical hands. When they are active, they create relationships among themselves, and this can be compared to the embodiment in the sense world of thoughts in speech, a pale reflection of the spiritual reality. We can accustom ourselves to experience the living thought-entities in the spiritual world. What they do, what they are, and the way they affect one another, forms a spirit language. One spirit being speaks to another; thought language is spoken in the realm of the spirit! However, this thought language in its totality is not only speech but represents the deeds of the spiritual world as well. It is in speaking that these beings work, move, and take action. When we cross the threshold, we enter a world where thoughts are entities, entities are thoughts; however, these beings of the spiritual world are much more real than people of flesh and blood in the sense world. We enter a world where the action consists of spiritual conversation, where words move, here, there, and everywhere, where something happens because it is spoken out. We have to say of this spiritual world and of the occurrences there what is said in Scene Three of The Guardian of the Threshold:

All occult perception attained for mankind by the initiates of every age could behold the significance in a certain realm of this spirit conversation that is at the same time spirit action. It was given the characteristic name, “The Cosmic Word.” Now observe that our study has brought us to the very center of the spiritual realm, where we can behold these beings and their activities. Their many voices, many tones, many activities, sounding together, form the Cosmic Word in which our own soul being—itself Cosmic Word—begins to find itself at home, so that, sounding forth, we ourselves perform deeds in the spiritual world. The term “Cosmic Word” used throughout past ages by all peoples expresses an absolutely true fact of the spirit land. To understand its meaning at the present time, however, we have to approach the uniqueness of the spiritual world in the way we have tried to describe in this study. In the various past ages and peoples, occult knowledge has spoken with more or less understanding of the Cosmic Word; now, too, it is necessary, if mankind is not to be devastated by materialism, to reach an understanding for such words about the spiritual world, from the Mystery Drama:

It is imperative in our time that when such words are spoken out of the knowledge of the spiritual world, our souls should feel their reality, should feel that they represent reality. We must be aware that this is just as much an exact characteristic of the spiritual world as when in characterizing the physical sense world we apply ordinary sense images. Just how far our present age can bring understanding to bear on such words as “Here in this place words are deeds and further deeds must follow them” will depend on how far it takes up spiritual science and how well people today will be prepared to prevent the dominating force of materialism that otherwise will plunge human civilization into impoverishment, devastation and decay.

|

| 196. Spiritual and Social Changes in the Development of Humanity: Tenth Lecture

06 Feb 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Picture to yourself today Newton, who formulated that astronomical world view of which Herman Grimm rightly says: “As one imagines it in the sense of this astronomical world view, that the earth and the planetary system of the sun emerged from a haze, a thin mist, that transformed and transformed, that then from this vortex also animals, man and plants also arose from this vortex, and that one day the whole will fall back into the sun, is a carrion bone around which a hungry dog circles, a more appetizing piece than this world view; and times to come will have a hard time understanding the cultural and historical madness of the Newtonian, Kant-Laplacean system that is taught in school today. People will ask: How could an entire age once be so insane as to praise this view? |

| 196. Spiritual and Social Changes in the Development of Humanity: Tenth Lecture

06 Feb 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

In our recent reflections here, we have been speaking of the necessities of the time. Today, man must be content to absorb the impact that wants to enter the physical world. We have seen how, for about sixty years, there has been a struggle in the most intense way in European life, which began in the last third of the 19th century and contains the causes of all the confusions of these last times. I have pointed out to you the fact that what is happening is still being taken too lightly, in that people do not want to admit that old Europe has led a sham existence in the 20th century, has broken up and cannot be glued back together. This crisis can be compared to a crisis such as occurred in the ancient Roman Empire, when Christianity gradually broke into this Roman Empire and swept away everything that existed. Something completely new has developed. Anyone who has insight into life will realize that everything that has been built up since the first Christian century has been shattered. Let us now take a look at what has been built up. The Mystery of Golgotha was there. But the Mystery of Golgotha and its understanding are two different things. Let us make this clear by means of a comparison. Suppose you look at a person who has this or that as the content of his soul or as the impulse for his actions. If a child looks at such a person, it forms a judgment; but this is a childlike view. A person who has learned something, who is an adult, will then also be able to form an opinion about this person; this will be a more mature view. But not everyone who has a mature view will be able to have sufficient knowledge or insight into the person in question, if that person is, for example, a genius. For this it would be necessary that in turn a genius would have formed his view about this person. So we have a fact in this case: a person can be there, and there can be different understandings of this fact. — This is how it is in the course of time with the event that Christianity brought into the world. This event as such was once there, it stands at the starting point of our modern civilization. The understanding that has been shown for Christianity until now is rooted essentially in the views, in the ideas, in the concepts that people could have from those soul foundations that had taken the place of the soul foundations of the old Roman Empire. To substantiate this, you need only look at the lost Austria, which, with the exception of a few outstanding personalities, had a culture – not just a spiritual culture, but a culture in the full breadth of life – that basically went back to the first Christian centuries. There the seeds of decay begin. People did not want to believe it, but anyone familiar with the circumstances could see it. And so it was in the rest of Europe. Europe was built on very old ideas, and thus in an old spirituality. And out of these ideas the Mystery of Golgotha was also understood. But these ideas are now worn out. They are no longer sufficient to convey an understanding of the event of Golgotha to the present-day human being. Man wants to stick to the old ideas because of his conservative tendencies. But in the depths of the soul there are definitely demands for a re-creation of Europe and the whole civilized world. This is the great struggle that has been evident at the basis of European culture for about sixty years. Something wants to be formed, but the preserved ideas of people are pushing it back. When a river current is dammed up somewhere, a rapid will eventually appear. This rapid has come to European culture. These are the years of terror that have befallen us, that are by no means over yet, and that are actually only just beginning. What is needed today is to establish a new conception of life based on spiritual principles. Those who today oppose such a conception of life are like those who, when Christianity spread from south to north, opposed it. The wave of evolution sweeps over such people. But such people can cause much harm, and much harm will still be caused by such people. Let us take a concrete example. If you look at how the situation developed that could be seen before 1914 and also, in a sense, during the last few years, when the catastrophe began, you will see that there were certain so-called state borders on the map of Europe. Why these state borders have developed in this way over the centuries can be traced through history. But it is precisely from a true, unprejudiced consideration of history that you will gain the insight that these states, from the great Russia to the smallest entities, came into being under the influence of the understanding of Christ, that is, the understanding of Christ as it took hold in Europe at the time of the so-called migration of peoples, at the time of the decadence of the Roman Empire. In 1914, to give a date, these conditions, which found expression in these 'strokes' that demarcated states on the map of Europe, were all already unnatural. There was nothing true about these borders. There was nothing there that had any inner hold. And anyone today who believes that anything can be held together by what was no longer true in 1914 has clearly gone down the wrong path. Even that which has been or wants to be formed on the basis of these conditions is no longer tenable. What do the people of Europe with their American appendage now want to do with the civilized world? Let us take an unbiased look at what the people of Europe with their American appendages currently want to do with the civilized world. They want to do what might have emerged in the first centuries A.D., in the migrations of nations, from the ideas that the Goths, the Vandals, the Lombards, Heruls, Cherusci, and so on had, and that the Romans had before they were seized by Christianity. It did not come about, although at that time people did not even resist the course of events as strongly with their consciousness as they do today. But let us hypothetically assume that in those days they would not have allowed Christianity to spread, but would have wanted a Europe glued together from the ideas of the Ostrogoths and Visigoths, the Vandals, the Lombards and so on, with the remnants of ancient Roman civilization – an impossibility, pure and simple! A possible Europe only arose from the fact that a spiritual impact came to this Europe. And this spiritual impact came through Christianity. Without this spiritual impact, which has made everything different, nothing would have come of Europe for the centuries from the 4th, 5th to the 20th century. Imagine Europe without the impact of Christianity in the past centuries: you could not imagine it. Just think of what remains of the Goths, the Heruls, the Langobards and so on in Europe. You have to admit: the impact of Christianity was enormous and everything changed. If, in those days, the Lombards had rejected every new impulse just as much as, for example, the Czechoslovaks or the Poles or the French reject it today, then what I hypothetically assumed, the impossible, would have happened. And just as the Lombards would have behaved if they had said, “We do not want Christianity, we want to remain Lombard,” so today the Czechoslovaks, the Magyars, the French, the English and so on are behaving. They do not want a new spiritual impact. But Europe is at rock bottom without a new influence. Nothing comes of it. Just as little comes of Europe as of a Goth, Lombard, or Vandal Europe when Christianity was ripe to make its impact on European civilization. This thought is one that the vast majority of people today fear. You may be surprised if I say that they are afraid, because you believe that it is for these or those reasons of life or logical or other reasons that they resist this thought. That is not the case. The reason why they resist is subconscious fear. When you have subconscious fear, you do not understand things. One invents logical reasons, one invents all kinds of observations that one believes one has made in order to refute this thought, while one is actually afraid of it. But man does not admit to fear! But the time is so great that it is necessary to look into these circumstances without fail. And it is necessary to speak words today that will certainly sound paradoxical to a large proportion of people. When it first spread, Christianity also sounded paradoxical to people. You should just imagine what it sounded like when the spreaders of Christianity came, say, to Alsace or Switzerland, where they still worshipped the images of Odin, the god Saxnot and so on. It was something paradoxical. Today it is paradoxical for people when one speaks to them of what anthroposophically oriented spiritual science must speak of as a new impact and at the same time as a new understanding of Christianity. Only today everything must become conscious, only today everything must be more willed than people in those days were capable of wanting. Above all, one thing must be grasped by humanity today with all its sharpness. We have a so-called scientific, intellectual life. In my last Sunday lecture I characterized one aspect of this intellectual life; I pointed out to you the character that this intellectual life has acquired through the English-speaking population. Do not believe that this intellectual life leaves anything to chance. What our children learn at school, from the age of six, shapes their souls, shapes the whole person, and people today walk around as they are shaped by our school system, which in its lower levels is strongly influenced, especially today in the age of the proliferation of the newspaper industry, much more than one might think, is influenced to a great extent by what is so-called science in the upper echelons of intellectual life. Science has had its great external successes. It has brought about the telephone and air travel, and it has brought about wireless telegraphy. In all these fields, it has made great achievements. But I have repeatedly drawn your attention to a peculiarity of this science, a peculiarity of our entire knowledge. This peculiarity consists in the fact that we can understand everything. We can understand machines, we can understand minerals, we can understand plants, we can understand animals, but we can least of all understand the human being through what our science presents. That one infers man directly from animality, that one says he is only a higher stage of development of animality, that comes only from the fact that one does not know anything about man. Not because man really comes from the animal, but because one does not know anything about the true man, but can only reveal the idea that one has, one leaves man coming from the animal kingdom. It is only a prejudice of the age that has no science with which to judge man. Therefore, we are also incapable in the present time of acquiring a real knowledge of human nature from our own education. By knowledge of human nature cannot be meant that conglomeration of all sorts of ideas that man today has of himself. A true knowledge of human nature could only arise out of the realization of what the true human being, the genuine human being, is made of. Even if we study everything we have on earth, study with the means of today's science, we can build machines with it, we can design mechanisms with it, but we can never understand the human being with it. That is precisely what anthroposophical spiritual science is for: to make man comprehensible from extraterrestrial conditions. People feel this, but in their current ideas they do not admit that man today must be understood from extraterrestrial, from supersensible conditions. And so there is no science for this man. For centuries the world has been deluding itself about this fact in a strange way. I would like to show you, using one example (of which there are many), how this fact has been ignored over the centuries. When the time had come to present to you, as an anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, what has been developed here over the past few years, some people who had come close to what I, for example, had given on the basis of this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, said: We prefer to delve into the mysticism of Meister Eckhart, into the mysticism of Johannes Tauler. There everything is much simpler; there one can comfortably say: I immerse myself in my inner being, I grasp the higher human being in me, my higher self has grasped the divine human being in me. — But that is nothing more than sophisticated egotism, nothing more than a retreat into the egoistic personality, a running away from all humanity, an inward self-deception. When, in the 14th and 15th centuries, people began to fail to understand their fellow human beings, it was clear that spirits such as Johannes Tauler and Meister Eckhart would have to arise to point to the human soul in order to seek the human being. But today that time is over. Today this deepening and sinking into the inner being is no longer good. Today it is about really understanding a Christ-word correctly - that is the example I mean - this one Christ-word, which is one of the most important, the most significant, that is: “If two or three are united in my name, then I am in the midst of you.” That means that if someone is alone, the Christ is not there. One cannot find the Christ without feeling connected to all of humanity. Today, one must seek the Christ through the path that all of humanity is walking. That is to say, inner satisfaction leads away from the Christ impulse. This is the misfortune, especially for 19th-century Protestant theology, that the impulse arose to have a mere individualistic, egoistic inner Christ experience. There is a crowned head in Europe, one of those who are still crowned, who always replied when it came to contemporary spiritual knowledge: “I have my personal Christ experience!” This crowned head was satisfied with that. But many say similar things. That, however, is precisely the misfortune of the present time: people do not want a general interest in the impersonal human. You only get to know yourself when you know the human being as such. But you cannot get to know the human being as such without seeking his origin in extra-terrestrial conditions. Consider how, in my book Occult Science, I describe the search for the origin of what we call man in extraterrestrial conditions. People dislike this “Occult Science” for no other reason than because all confused knowledge about humanity is rejected and man as such is derived from the whole universe, namely from the extraterrestrial universe. But this is precisely what is needed in today's world. The present time must decide to add the other, the spiritual sources of knowledge to all that is loved as sources of knowledge today. Here lies, call it guilt, call it ignorance – either word may be used, words are not important – what must be characterized as emanating from our scientific universities, from those people who set the tone when it comes to what man can and cannot know. The so-called human wisdom, but also the social wisdom, the technical wisdom, etc., that emanates from our European and American universities regards the world with the exclusion of all those factors that, after all, include the human being as a matter of course. Anyone who seeks access to any leading position today, even a lowly one, has no opportunity to get to know anything that would enable him to gain knowledge of human nature. And without knowledge of human nature there can be no social life, and without knowledge of human nature there can be no renewal of Christianity. Today one can become a theologian without having the slightest idea what the Mystery of Golgotha means, for most theologians today have no idea who Christ is. Today one can become a lawyer without having the slightest idea what the human being actually is. One can become a physician today without having the slightest idea of how the human being is constructed out of the cosmos, without having the slightest idea of how a healthy and a sick body relate to each other. Today one can become a technician without having the slightest idea what influence the construction of any machine has on the whole course of earthly development, and today one can be a brilliant inventor of a telephone without having the slightest idea what the telephone means for the whole development of the earth. People lack an overview of the course of human development. And so every person has the need to form a small circle and acquire a routine within this small circle, to apply this routine in the sense of their own selfishness, so that they can distinguish themselves without considering how what they are inserting as a part into the whole world will turn out in this whole world. If we were to build houses in the world using the same method by which we establish our existence today, they would collapse immediately. If we were to form bricks and build houses using the same method by which we educate our theologians, our lawyers, physicians, philologists and so on, and in particular our philosophers, these houses would not be able to survive for a week in the whole of the world. In the grand scheme of things, people do not notice the collapse. It has been collapsing continuously since the last third of the 19th century. People know nothing about it; on the contrary, they talk about the great upturn, and some still talk about building a new world with the same bricks that have long since become unusable. A new world cannot be built in any other way than by bringing a new spiritual impact into the whole civilized world from the ground up. You can make a mockery of something, but you cannot build without this spiritual impact. There are people - well-meaning people - who are terribly afraid of such an intensity of knowledge, of such an intensity of knowledge as is sought through spiritual science. They are afraid for a reason – I am not telling you something I made up, only things that correspond to facts – they say to themselves: How boring it will be when people will know everything that spiritual science claims to know; then one can no longer hope that the future will bring new knowledge, then one cannot even know that knowledge will help. They still think that it would be a terrible prospect for the future if everything were already known! I am not saying that this is convenient information for those who are too lazy to approach knowledge, but I would like to point out that the moment man is seen as he can be seen through spiritual science, the possibility of thinking about social construction really begins. You cannot establish social construction in any other way than by first bringing human knowledge into the clear, so to speak. To make this clear, one must only say the following: Take everything that leads to our present-day communities. People do not owe it to their enlightenment; they do not owe it to the ideas that they have fully absorbed into their consciousness, they owe it to those spiritual forces that shine through the blood, which have sprung from the old blood connections, blood relationships. Even today we still have something that enters our world as a remnant of that old blood relationship, which is given to us by the national principle and comes to the fore in it. The reason why one person calls himself an Englishman, another a Frenchman, and a third a Pole, stems from all those relationships between people that have always been based on blood ties. This blood relationship had its good justification through the thousands of years of human development, because through this blood relationship that which brought people together, that which founded human communities, rose up into humanity. And as you can see from my “Occult Science”, at the beginning of the development of the earth, people were not at all so uniform. The human souls came to earth from the most diverse places, as you know, and did not truly love each other. They only learned to love each other by being born as souls into blood-related bodies. In earlier lectures I repeatedly showed how the beneficence of this blood relationship, blood community, has been fought by the powers opposed to man, by the luciferic-ahrimanic powers. That was in ancient times. Then people were dependent on having human communities founded on blood ties. Today, to believe that one only needs to translate the old principle of blood relationship into the abstract language and that one can say, by clothing the abstractness in “Fourteen Points”: To every single, even the smallest people, its right to self-determination! One must be Woodrow Wilson in his unworldliness, in his abstraction, if one can do such a thing. Today one must realize: that was once. Blood relationships once established human communities. Today, however, other forces are at work in the ahrimanic and luciferic powers that are opposed to humanity. Today, blood relationship is to be used to seduce people. Just as the Christ did not come into the world to abolish the law, but to take it up into Himself, so blood relationship is not to be done away with. On the contrary, blood relationship must first be guided in the right way. But whereas in ancient times the Ahrimanic and Luciferic beings in human hearts opposed blood relationship and sought to split human beings into egoistic individuals, today the Ahrimanic and Luciferic powers seek to seduce human beings are to be seduced into building only on the blood relationship. Today the time has come to recognize that every human being who really has body, soul and spirit and stands before us comes down from the spiritual world. He comes down from the spiritual world in such a way that he has gone through a pre-earthly life. He seeks out for himself the blood through which he wants to embody himself on earth. And a feeling for this spiritual community must gradually arise. In pre-Christian times, reincarnation existed as a feeling, for it was only a realization before the year 1860 before Christianity; after the year 1860 it was only an instinctive feeling in all of Egypt, in the Near East, in Roman times. But now the time is coming when the view of man as a spiritual being undergoing a development between death and a new birth will become a living feeling, a living sensation, when one must live with the idea of the supermundane significance of human souls. For without this idea, the culture of the earth will be killed. It will not be possible to develop a practical activity in the future without being able to look up to the spiritual significance of the fact that every human being is a spiritual being. And one will have to add, as paradoxical as this may still appear to today's man – less paradoxical in theory, for I do not want to theorize, but to parallelize, in terms of feeling, but it is nevertheless so – that one will have to learn not only to say to oneself: We as parents rejoice that a child is born to us, we rejoice at this addition to our family because this child is born to us – but one will have to say: No, we are merely the instrument through which a spiritual individuality, waiting to continue its existence on earth, finds the opportunity to do so through us! The aristocratic idea of the “Stammhalter” (the son who continues the family line) and the aristocratic idea of the mere continuation of the family bloodline, for example, will have to be among the antiquated things. And the feeling will have to extend to all humanity. Even today, aristocrats still have the attitude that their primary task is to continue their family line so that the physical person has descendants with the same name. The feeling will have to be reversed to the effect that one must have these successors in the service of all humanity, so that certain individualities, who want to descend to the world, can continue their existence here on this earth. The old sentiments in aristocracy, in family aristocracy, extend into our present time. The feeling of that general human knowledge must be opposed to this; then we will also be able to understand the Christ anew. For He did not come to earth for the sake of family egoism, but for the sake of all mankind. Nor did He come for the sake of any nationality, but for the sake of all mankind. He did not come so that those who call themselves the victors could establish nation-states, but so that the universal human element could be cultivated on earth within the framework of nationality. These things are at the root of what is happening now. And they are so rooted that what is being sought in earthly existence today is opposed by what the majority of people still say and want today. But if people continue to want things, they will only establish things that lead themselves ad absurdum, that lead themselves into impossibility. Either one will realize this, or one will have to wade in the European chaos for a long time to come. It is the best means to continue wading in this European chaos by founding nation states. For this reason, we had to speak of the great responsibility to those who will soon fall outwardly to world domination. This responsibility is there. The English-speaking population has this terrible responsibility before the world, no longer to reject the spiritual, no longer to be Baconian or Newtonian, but to take up the spirit in its new form. Picture to yourself today Newton, who formulated that astronomical world view of which Herman Grimm rightly says: “As one imagines it in the sense of this astronomical world view, that the earth and the planetary system of the sun emerged from a haze, a thin mist, that transformed and transformed, that then from this vortex also animals, man and plants also arose from this vortex, and that one day the whole will fall back into the sun, is a carrion bone around which a hungry dog circles, a more appetizing piece than this world view; and times to come will have a hard time understanding the cultural and historical madness of the Newtonian, Kant-Laplacean system that is taught in school today. People will ask: How could an entire age once be so insane as to praise this view? Today it is still considered madness to side with Goethe against Newton, to occupy oneself with Goethean conceptions about physical phenomena. But everything that lies within the tasks of our time is connected with these things. A few people are beginning to see these connections today, and it was a pleasant surprise for me when, in the last issue of our journal 'Die Dreigliederung', it was explained how what is in my book 'Die Kernpunkte der sozialen Frage' about the social understanding of the world means the same as what Goetheanism once meant for natural science. But just as people turned away from Goethe because he had to contradict the science of his time, so people today turn away from the threefold social order. Why? It contradicts what is customary, just as Goetheanism once did, so that it is also contradicted by this threefold social order. These things can lead you to ask: But what should the individual do then? — First of all, it depends on one's attitude towards the matter, on a clear and objective examination. It is important that one really begins to develop a deep interest in the affairs of all humanity. You can look back on what you have experienced in the last four to five years, and never have you had more opportunities to meet a certain kind of know-it-all in the world over and over again, because basically every person was a know-it-all. Then the Germans came and knew exactly who was to blame for the war and that they were actually highly innocent; then the French came and knew exactly how everything was; then the Italians at least still stood for “sacro egoismo”. — People always knew exactly what it was all about. They all had their views, they had their thoughts, their ideas. It is indeed convenient to gain these ideas without any basis. One is French by blood, one is Polish by blood, one is Czechoslovakian by blood, and one has a certain view of life as it must develop in Europe. One does not need to do anything other than this or that, to feel it within oneself, and one judges, judges as one is confronted with the judgments. That is the great misfortune of our time: that people, without really making an effort, without taking an interest in the affairs of humanity, judge from their subconscious, consider this or that to be right, consider this or that to be indispensable. But the time is no longer there when one can consider this or that to be indispensable from one's subconscious. The time has come when we must judge only on the basis of facts, when we must make an effort to really get an overview of the necessity of the time and of what the time demands of us. Today it constricts one's heart when one meets people who are only interested in themselves. For that is the great misfortune of our time, while the only redemption of time could consist in people saying to themselves now, after the terrible things that have happened in recent years: We must take an interest in the affairs of all humanity, we must not stop at what is happening directly around us in the sphere of our own nation. These things arise directly from spiritual science as intuitive perceptions, and I am speaking of them today in preparation for certain concluding thoughts. You see here this building, which is the representative of our Anthroposophical spiritual science. One can have feelings for one or other of the elements in this building, and one will be right. But the only person who has the right feeling for this building is the one who sees something in every single line that is demanded by the most urgent needs of our time. The person who sees that the building must stand because our time demands this or that, because this or that must be sensed in these or those columns, in these or those rows of windows; because it is necessary for humanity today to take this building, what it wants to be, out of the whole configuration of time. And anyone who feels this new style at the same time, once they have felt it through, will recognize that this style has absolutely nothing to do with anything that is specified for this or that, but that it has only to do with the most general human aspects. There is nothing about this entire structure that the American, the Englishman, the German, the Russian, the Japanese, or the Chinese cannot say yes to, because it is not shaped from the sensibilities of a single person. I will not be able to be portrayed, at least not by those who know me, as an immodest person when I say: I myself know of nothing that is currently being made of this kind that is as independent of differentiated human will and would merge into the most general knowledge and understanding of human nature as this building. But this must be taken up if the things that arise from our motives for the future of humanity are to serve that future well. |

| 196. Spiritual and Social Changes in the Development of Humanity: Fourteenth Lecture

14 Feb 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| What has become of humanity through abstraction, through mere abstraction, appears only in symptoms in such philosophies as those of the American William James, the Englishman Spencer, the Frenchman Bergson or the German, Königsberg Kant. These abstractions conceal from humanity what it is. But the living knowledge of the spiritual, which is to be striven for through spiritual science, can bring man to self-knowledge. |

| 196. Spiritual and Social Changes in the Development of Humanity: Fourteenth Lecture

14 Feb 1920, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

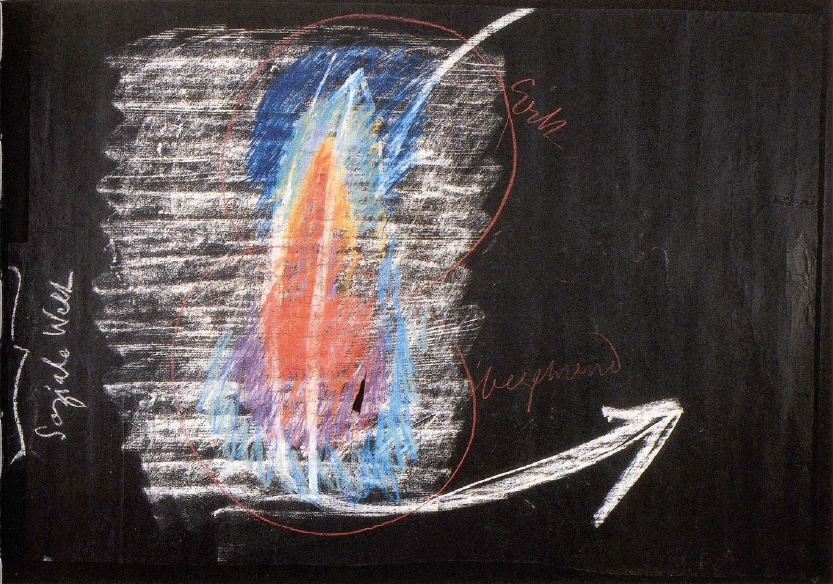

I shall very briefly draw attention once more to what I presented to you here yesterday, because today I shall have further things to add that relate to the human being. What I had to say to you yesterday was as follows: We first turned our attention to the three faculties of the human soul that are more devoted to knowledge. We pointed out that there are essentially three cognitive faculties in the human soul: first, what is the faculty of memory, then what is intelligence, and finally what is sensory activity. Now I drew your attention to the fact that these three soul faculties can only be understood by looking at their development. In order to understand memory, which is relatively one of the more recent abilities of the human being, we must turn our gaze back to times when the Earth was not yet what it is today, when the Earth was undergoing its development as the Moon, which preceded the Earth. So that the first rudiments of what has now become our faculty of memory are to be sought in the ancient lunar period and there appeared, not as memory, but as the dream-like imagination that pervades the human being, which I have often described in other contexts. What was dream-like imagination in the ancient moon period in the beings from which man developed has become the faculty of memory in the earth period. This memory, as I have already mentioned, is more closely interwoven with the physical body than are the other cognitive faculties of the soul. Intelligence is less closely interwoven with the physical body. It is more detached from it, as I described yesterday. But to discover its first rudiments, one must go further back than the old moon time; one must go back to the old sun time and then find the first rudiment of what is present in us today as intelligence in dormant inspiration. As for that which is most divorced from our physical nature, as I explained yesterday, one must go back furthest, although one is least inclined to believe this from the materialistic point of view of our time: for sensory activity, one must go back to the old Saturn time. And one finds as the first origin of this sensory activity, both beings, from which man was later formed, a dull intuition. Furthermore, we have seen that by carrying these three soul abilities within us, we are at the same time the hosts for beings of higher hierarchies in the organization that underlies these soul abilities. So that through the organization of our sensory activity, we are the hosts of the archai, the spirits of time. They live in our humanity. Through that which we have in us as intelligence, insofar as this intelligence is bound to the mirroring apparatus in us, which reflects back to us our concepts, our ideas, but which come from the spiritual world, and thus brings them to our consciousness, we are the hosts of the archangeloi. And through that which works in our organization and mediates our memory, we are the hosts of the angeloi. Thus we are related to the past through our cognitive abilities, and we are related to the beings of higher hierarchies through our cognitive abilities.  According to an old custom, these three abilities of man are called the upper abilities. And if I am to sketch the human being schematically for you, if I am to present the image of the human being to you as in a diagram, then I would have to draw the following as this diagram of the human being. I would have to start by drawing the faculty of sensory activity. I will try to do it like this, by making a white background (see drawing, hatched in white). I would first have to draw the sensory activity schematically in the human organization, and to get the right proportions, I would have to draw it like this (blue). The main sensory activity is, of course, developed in the head. Although the whole person is imbued with sensory activity, I would first like to draw the main sensory organization here (blue). If I wanted to draw in the intelligence, I would have to draw it in the following way to make it visible: sensory activity more outward (blue); the intelligence (green) has its mirroring apparatus more in the brain. Deeper down, what underlies memory is already very much connected to the physical organization. In reality, memory (red) is connected to the lowest nervous organisms and to the rest of the organism. I could then create transitions between sensory activity and intelligence by drawing this (indigo) here as a transition. You know that we also have concepts and ideas that are, so to speak, of a descriptive nature. While I have to draw the sensory activity as such in blue, I would have to draw an indigo here as a transition. For the more abstract concepts I would have to draw green, and for that which is in us as memory-based concepts, I would have to draw yellow as a transition from green to red through orange. In this way, I would have to draw the human being in its organization in relation to the ability to perceive, going from the outside in. In the succession of these colors, if you imagine the organization of eyes and ears with blue nuances and that the activity of the senses passes over into the intelligence, the indigo towards the green, lightening through the yellow to the red towards the memory, you get a kind of scheme that, however, very strongly reflects the reality of what the human soul's cognitive abilities or cognitive abilities are. Now, in human nature, everything plays together in a mess. That is what makes it so difficult for the materialistically thinking person, that in human nature everything plays together in a mess. You can't neatly separate one thing from another in space. In human nature, too, it is not so clearly defined, but if one wants to draw schematically, one can still get a relatively clear picture of all sorts of things. Thus, one can indeed see that the ability to remember is related to the ability to think through their inner properties in the same way that the color red relates to the color green; and just as green relates to blue, so does intelligence relate to the activity of the senses. Now, however, we have other abilities in the human soul, abilities that are more or less bound to physical corporeality in the strictest sense in us as earth people. Feeling belongs to these first. While memory, intelligence and sensory activity are bound to the awakening consciousness in stages, feeling is already something very 'dreamlike' in the human being. I have often explained this. While memory is something that developed in the distant past on the old moon, intelligence on the sun, sensory activity on Saturn, feeling, as we have it today, belongs to the human being on earth. It is essentially something that is bound to the human earthly organization. What we as terrestrial human beings received as an organization actually made us sentient beings in the first place. But just as memory is something that has gone beyond its first disposition and has come to a higher level of development on Earth, and if one has enough of a supersensible vision to recognize that memory is, so to speak, an old human ability, one recognizes that feeling is only present in its disposition. If we look at what the human being calls feeling today with the necessary understanding, we can see that in the future it will develop into something quite, quite different. Just as if, as an observer during the old moon time, we had looked at dreaming imagination and said to ourselves: This will later become the memory of man. In the same way, when we look at feeling today, we must say, understandingly: When the earth will no longer be, but something else will have come out of it, when the earth will have become the future Jupiter, then feeling will have become what it can become. Today, feeling in man is still only embryonic, something that exists as a germ. What it can become will only arise out of feeling. Thus, in feeling, we carry within us something that relates to what it becomes on Jupiter, just as a child in the womb relates to the human being born into the world. Our feeling is embryonic, and it will only later, during the Jupiter period, become that which will flourish as a complete, fully conscious imagination. Another soul faculty that is tied to our organization is desire. This desire is still much more embryonic than feeling. Everything in our world of desire will only become what it is now germinating towards during the future Venusian age. Today our desires are very closely bound up with our physical organization. They will become detached. Just as our intelligence was bound during the old sun time to the physical organization of the sun, as I have described it in my “Occult Science in Outline”, so is the world of desires of man today bound to the physical organization. It will appear detached from the physical organization during the future Venus period, and it will then appear as fully conscious inspiration. Among our soul abilities, the will is most embryonic. In the future, the will is called upon to become something very powerful, something cosmic, through which the human being will belong to the whole cosmos in the future, will be an individual being and yet will live out his individual impulses as a fact of the world. But this will only be during the volcanic age, when the will will be fully conscious intuition. Upper abilities

Lower abilities: Social World