| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Third Meeting

26 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Third Meeting

26 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

[The meeting began with a discussion of some children Dr. Steiner had observed that morning.] Dr. Steiner: E. E. must be morally raised. He is a Bolshevik. A teacher who was substituting in the first grade poses a question. Dr. Steiner: You should develop reading from pictorial writing. You should develop the forms from the artistic activity. A teacher suggests beginning the morning with the Lord’s Prayer. Dr. Steiner: It would be nice to begin instruction with the Lord’s Prayer and then go on to the verses I will give you. For the four lower grades I would ask that you say the verse in the following way:

The children must feel that as I have spoken it. First they should learn the words, but then you will have to gradually make the difference between the inner and outer clear to them.

The first part, that the Sun makes each day bright, we observe, and the other part, that it affects the limbs, we feel in the soul. What lies in this portion is the spirit-soul and the physical body.

Here we give honor to both. We then turn to one and then the other.

This is how I think the children should feel it, namely, the divine in light and in the soul. You need to attempt to speak it with the children in chorus, with the feeling of the way I recited it. At first, the children will learn only the words, so that they have the words, the tempo, and the rhythm. Later, you can begin to explain it with something like, “Now we want to see what this actually means.” Thus, first they must learn it, then you explain it. Don’t explain it first, and also, do not put so much emphasis upon the children learning it from memory. They will eventually learn it through repetition. They will be able to read it directly from your lips. Even though it may not go well for a long time, four weeks or more, it will go better later. The older children can write it down, but you must allow the younger ones to learn it slowly. Don’t demand that they learn it by heart! It would be nice if they write it down, since then they will have it in their own handwriting. I will give you the verse for the four higher classes tomorrow. [The verse for the four higher grades was:]

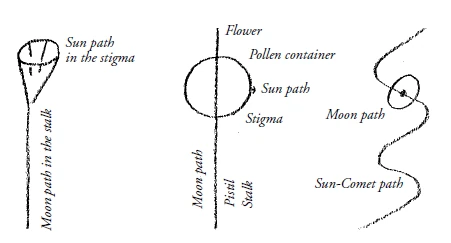

[The texts of the verses are exactly as Dr. Steiner dictated them according to the handwritten notes. It is unclear whether he said, “loving light” (liebes Licht) or “light of love” (Liebeslicht).] [Lesson plan for the independent anthroposophical religious instruction for children:] Dr. Steiner: We should give this instruction in two stages. If you want to go into anthroposophical instruction with a religious goal, then you must certainly take the concept of religion much more seriously than usual. Generally, all kinds of worldviews that do not belong there mix into religion and the concept of religion. Thus, the religious tradition brings things from one age over into another, and we do not want to continue to develop that. It retains views from an older perspective alongside more developed views of the world. These things appeared in a grotesque form during the age of Galileo and Giordano Bruno. Modern apologies justify such things—something quite humorous. The Catholic Church gets around it by saying that at that time the Copernican view of the world was not recognized, the Church itself forbade it. Thus, Galileo could not have supported that world perspective. I do not wish to go into that now, but I mention it only to show you that we really must take religion seriously when we address it anthroposophically. It is true that anthroposophy is a worldview, and we certainly do not want to bring that into our school. On the other hand, we must certainly develop the religious feeling that worldview can give to the human soul when the parents expressly ask us to give it to the children. Particularly when we begin with anthroposophy, we dare not develop anything inappropriate, certainly not develop anything too early. We will, therefore, have two stages. First, we will take all the children in the lower four grades, and then those in the upper four grades. In the lower four grades, we will attempt to discuss the things and processes in the human environment, so that a feeling arises in the children that spirit lives in nature. We can consider such things as my previous examples. We can, for instance, give the children the idea of the soul. Of course, the children first need to learn to understand the idea of life in general. You can teach the children about life if you direct their attention to the fact that people are first small and then they grow, become old, get white hair, wrinkles, and so forth. Thus, you tell them about the seriousness of the course of human life and acquaint them with the seriousness of the fact of death, something the children already know. Therefore, you need to discuss what occurs in the human soul during the changes between sleeping and waking. You can certainly go into such things with even the youngest children in the first group. Discuss how waking and sleeping look, how the soul rests, how the human being rests during sleep, and so forth. Then, tell the children how the soul permeates the body when it awakens and indicate to them that there is a will that causes their limbs to move. Make them aware that the body provides the soul with senses through which they can see and hear and so forth. You can give them such things as proof that the spiritual is active in the physical. Those are things you can discuss with the children. You must completely avoid any kind of superficial teaching. Thus, in anthroposophical religious instruction we can certainly not use the kind of teaching that asks questions such as, Why do we find cork on a tree? with the resulting reply, So that we can make champagne corks. God created cork in order to cork bottles. This sort of idea, that something exists in nature simply because human intent exists, is poison. That is certainly something we may not develop. Therefore, don’t bring any of these silly causal ideas into nature. To the same extent, we may not use any of the ideas people so love to use to prove that spirit exists because something unknown exists. People always say, That is something we cannot know, and, therefore, that is a revelation of the spirit. Instead of gaining a feeling that we can know of the spirit and that the spirit reveals itself in matter, these ideas direct people toward thinking that when we cannot explain something, that proves the existence of the divine. Thus, you will need to strictly avoid superficial teaching and the idea of wonders, that is, that wonders prove divine activity. In contrast, it is important that we develop imaginative pictures through which we can show the supersensible through nature. For example, I have often mentioned that we should speak to the children about the butterfly’s cocoon and how the butterfly comes out of the cocoon. I have said that we can explain the concept of the immortal soul to the children by saying that, although human beings die, their souls go from them like an invisible butterfly emerging from the cocoon. Such a picture is, however, only effective when you believe it yourself, that is, when you believe the picture of the butterfly creeping out of the cocoon is a symbol for immortality planted into nature by divine powers. You need to believe that yourselves, otherwise the children will not believe it. You need to arouse the children’s interest in such things. They will be particularly effective for the children where you can show how a being can live in many forms, how an original form can take on many individual forms. In religious instruction, it is important that you pay attention to the feeling and not the worldview. For example, you can take a poem about the metamorphosis of plants and animals and use it religiously. However, you must use the feelings that go from line to line. You can consider nature that way until the end of the fourth grade. There, you must always work toward the picture that human beings with all our thinking and doing live within the cosmos. You must also give the children the picture that God lives in what lives in us. Time and again you should come back to such pictures, how the divine lives in a tree leaf, in the Sun, in clouds, and in rivers. You should also show how God lives in the bloodstream, in the heart, in what we feel and what we think. Thus, you should develop a picture of the human being filled with the divine. During these years, you should also emphasize the picture that human beings, because they are an image of God and a revelation of God, should be good. Human beings who are not good hurt God. From a religious perspective, human beings do not exist in the world for their own sake, but as revelations of the divine. You can express that by saying that people do not exist just for their own sake, but “to glorify God.” Here, “to glorify” means “to reveal.” Thus, in reality, it is not “glory to God in the highest,” but “reveal the gods in the highest.” Thus, we can understand the idea that people exist to glorify God as meaning that people exist in order to express the divine through their deeds and feelings. If someone does something bad, something impious and unkind, then that person does something that belittles God and distorts God into something ugly. You should always bring in these ideas. At this age you should use the thought that God lives in the human being. In the lower grades, I would certainly abstain from teaching any Christology, but just awaken a feeling for God the Father out of nature and natural occurrences. I would try to connect all our discussions about Old Testament themes, the Psalms, the Song of Songs, and so forth, to that feeling, at least insofar as they are useful, and they are if you treat them properly. That is the first stage of religious instruction. In the second stage, that is, the four upper grades, we need to discuss the concepts of fate and human destiny with the children. Thus, we need to give the children a picture of destiny so that they truly feel that human beings have a destiny. It is important to teach the child the difference between a simple chance occurrence and destiny. Thus, you will need to go through the concept of destiny with the children. You cannot use definitions to explain when something destined occurs or when something occurs only by chance. You can, however, perhaps explain it through examples. What I mean is that when something happens to me, if I feel that the event is in some way something I sought, then that is destiny. If I do not have the feeling that it was something I sought, but have a particularly strong feeling that it overcame me, surprised me, and that I can learn a great deal for the future from it, then that is a chance event. You need to gradually teach the children about something they can experience only through feeling, namely the difference between finished karma and arising or developing karma. You need to gradually teach children about the questions of fate in the sense of karmic questions. You can find more about the differences in feeling in my book Theosophy. For the newest edition, I rewrote the chapter, “Reincarnation and Karma,” where I discuss this question. There, I tried to show how you can feel the difference. You can certainly make it clear to the children that there are actually two kinds of occurrences. In the one case, you feel that you sought it. For example, when you meet someone, you usually feel that you sought that person. In the other case, when you are involved in a natural event, you have the feeling you can learn something from it for the future. If something happens to you because of some other person, that is usually a case of fulfilled karma. Even such things as the fact that we find ourselves together in this faculty at the Waldorf School are fulfilled karma. We find ourselves here because we sought each other. We cannot comprehend that through definitions, only through feeling. You will need to speak with the children about all kinds of fates, perhaps in stories where the question of fate plays a role. You can even repeat many of the fairy tales in which questions of fate play a role. You can also find historical examples where you can show how an individual’s fate was fulfilled. You should discuss the question of fate, therefore, to indicate the seriousness of life from that perspective. I also want you to understand what is really religious in an anthroposophical sense. In the sense of anthroposophy, what is religious is connected with feeling, with those feelings for the world, for the spirit, and for life that our perspective of the world can give us. The worldview itself is something for the head, but religion always arises out of the entire human being. For that reason, religion connected with a specific church is not actually religious. It is important that the entire human being, particularly the feeling and will, lives in religion. That part of religion that includes a worldview is really only there to exemplify or support or deepen the feeling and strengthen the will. What should flow from religion is what enables the human being to grow beyond what past events and earthly things can give to deepen feeling and strengthen will. Following the questions of destiny, you will need to discuss the differences between what we inherit from our parents and what we bring into our lives from previous earthly lives. In this second stage of religious instruction, we bring in previous earthly lives and everything else that can help provide a reasoned or feeling comprehension that people live repeated earthly lives. You should also certainly include the fact that human beings raise themselves to the divine in three stages. Thus, after you have given the children an idea of destiny, you then slowly teach them about heredity and repeated earthly lives through stories. You can then proceed to the three stages of the divine. The first of these stages is that of the angels, something available for each individual personally. You can explain that every individual human being is led from life to life by his or her own personal genius. Thus, this personal divinity that leads human beings is the first thing to discuss. In the second step, you attempt to explain that there are higher gods, the archangels. (Here you gradually come into something you can observe in history and geography.) These archangels exist to guide whole groups of human beings, that is, the various peoples and such. You must teach this clearly so that the children can learn to differentiate between the god spoken of by Protestantism, for instance, who is actually only an angel, and an archangel, who is higher than anything that ever arises in the Protestant religious teachings. In the third stage, you teach the children about the concept of a time spirit, a divine being who rules over periods of time. Here, you will connect religion with history. Only when you have taught the children all that can you go on, at about the twelfth grade, to—well, we can’t do that yet, we will just do two stages. The children can certainly hear things they will understand only later. After you have taught the children about these three stages, you can go on to the actual Christology by dividing cosmic evolution into two parts: the pre-Christian, which was really a preparation, and the Christian, which is the fulfillment. Here, the concept that the divine is revealed through Christ, “in the fullness of time,” must play a major role. Only then will we go on to the Gospels. Until then, to the extent that we need stories to explain the concepts of angel, archangel, and time spirit, we will use the Old Testament. For example, we can use the Old Testament story of what appeared before Moses to explain to the children the appearance of a new time spirit, in contrast to the previous one before the revelation to Moses. We can then also explain that a new time spirit entered during the sixth century B.C. Thus, we first use the Old Testament. When we then go on to Christology, having presented it as being preceded by a long period of preparation, we can go on to the Gospels. We can attempt to present the individual parts and show that the four-foldedness of the Gospels is something natural by saying that just as a tree needs to be photographed from four sides for everything to be properly seen, in the same way the four Gospels present four points of view. You take the Gospel of Matthew and then Mark, Luke, and John and emphasize them such that the children will always feel that. Always place the main emphasis upon the differences in feeling. Thus, we now have the teaching content of the second stage. The general tenor of the first stage is to bring to developing human beings everything that the wisdom of the divine in nature can provide. In the second stage, the human being no longer recognizes the divine through wisdom, but through the effects of love. That is the tenor, the leitmotif in both stages. A teacher: Should we have the children learn verses? Dr. Steiner: Yes, at first primarily from the Old Testament and then later from the New Testament. The verses contained in prayer books are often trivial, therefore, you should use verses from the Bible and also those verses we have in anthroposophy. In anthroposophy, we have many verses you can use well in this anthroposophical religious instruction. A teacher: Should we teach the Ten Commandments? Dr. Steiner: The Ten Commandments are, of course, in the Old Testament, but you should make their seriousness clear. I have always emphasized that the Ten Commandments state that we should not speak the name of God in vain. This is something that nearly every preacher overdoes since they continually speak vainly of Christ. Of course, this is something we must deepen in the feeling. We should not give religious instruction as a confession of faith, but as a deepening of feeling. The Apostles’ Creed as such is not important, only what we feel in the Creed. It is not our belief in God the Father, in God the Son, and in God the Holy Spirit, but what we feel in relationship to the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. What is important is that in the depths of our soul, we feel that it is an illness not to know God, that it is a misfortune not to know Christ and that not to know the Holy Spirit is a limitation of the human soul. A teacher: Should we teach the children about historical things, for instance, the path of the Zarathustra being up to the revelation of Christianity, or the story of the two Jesus children? Dr. Steiner: You should close the religious instruction by teaching the children about these connections but, of course, very carefully. The first stage is clearly more nature religion, the second, more historical religion. A teacher: Then we should certainly avoid teaching about functionality in natural history? Schmeil’s guidelines for botany and zoology are teleological. Dr. Steiner: With regard to books, I would ask that you consider them only as a source of factual information. You can assume that we should avoid the methods described in them, and also the viewpoints. We really must do everything new. We should completely avoid the books that are filled with the horrible attitude we can characterize with statements such as “God created cork in order to cork champagne bottles.” For us, such books exist only to inform us of facts. The same is true for history. All the judgments made in them are no less garbage, and in natural history that is certainly true. In my opinion it would not be so bad if we used Brehm, for example, if such things are to be up-to-date. Brehm avoids such trivial things, though he is a little narrow-minded. It would be a good idea to copy out such things and use stories as a basis. Perhaps, that would be the best thing to do. The old edition of Brehm is pretty boring. We cannot use the new edition written recently by someone else. In general, you can assume all school books written after 1885 are worthless. Since that time, all pedagogy has regressed in the most terrible way and simply landed in clichés. A teacher: How should we proceed with human natural history? How should we start that in the fourth grade? Dr. Steiner: Concerning human beings you will find nearly everything somewhere in my lecture cycles. You will find nearly everything there somewhere. You also have what I presented in the seminar course. You need only modify it for school. The main thing is that you hold to the facts, also the psychological and spiritual facts. You can first take up the human being by presenting the formation of the skeleton. There, you can certainly be confident. Then go on to the muscles and the glands. You can teach the children about will by presenting the muscles and about thinking by presenting the nerves. Hold to what you know from anthroposophy. You must not allow yourselves to be led astray through the mechanical presentation of modern textbooks. You really don’t need anything at the forefront of science for the fourth grade, so perhaps it is better to take an older description and work with that. As I said, all of the things since the 1880s have become really bad, but you will find starting points everywhere in my lectures. A teacher: I put together a table of geological formations based on what you said yesterday. Dr. Steiner: Of course, you should never pedantically draw parallels. When you go on to the primeval forms, to the original mountains, you have the polar period. The Paleozoic corresponds to the Hyperborean, but you may not take the individual animal forms pedantically. Then you have the Mesozoic, which generally corresponds to Lemuria. And then the first and second levels of mammals, or the Cenozoic, that is, the Atlantean age. The Atlantean period was no more than about nine thousand years ago. You can draw parallels from these five periods, the primitive, the Paleozoic, the Mesozoic, the Cenozoic, and the Anthropozoic. A teacher: You once said that normally the branching off of fish and birds is not properly presented, for example, by Haeckel. Dr. Steiner: The branching off of fish is usually put back into the Devonian period. A teacher: How did human beings look at that time? Dr. Steiner: In very primitive times, human beings consisted almost entirely of etheric substance. They lived among other things but had as yet no density. The human being became more dense during the Hyperborean period. Only those animal forms that had precipitated out, lived. Human beings lived also with no less strength. They had, in fact, a tremendous strength. But they had no substance that could remain, so there are no human remains. They lived during all those periods but only gained an external density during the Cenozoic period. If you recall how I describe the Lemurian period, it was almost an etheric landscape. Everything was there, but there are no geological remains. You will want to take into account that the human being existed through all five periods. The human being was everywhere. Here in the first period (Dr. Steiner points to the table), “primitive form,” there is actually nothing else present except the human being. There are only minor remains. There the Eozoic Canadensa is actually more of a formation, something created as a form that is not a real animal. Here in the Hyperborean/Paleozoic period, animals begin to occur, but in forms that later no longer exist. Here in the Lemurian/Mesozoic period, the plant realm arises, and here in the Cenozoic period, Atlantis, the mineral realm arises, actually already in the last period, in these two earlier periods already (in the last two sub-races of the Lemurian period). A teacher: Did human beings exist with their head, chest, and limb aspects at that time? Dr. Steiner: The human being was similar to a centaur, an extremely animal-like lower body and a humanized head. A teacher: I almost have the impression that it was a combination, a symbiosis, of three beings. Dr. Steiner: So it is, also. A teacher: How is it possible that there are the remains of plants in coal? Dr. Steiner: Those are not plant remains. What appears to be the remains of plants actually arose because the wind encountered quite particular obstacles. Suppose, for instance, the wind was blowing and created something like plant forms that were preserved somewhat like the footsteps of animals (Hyperborean period). That is a kind of plant crystallization, a crystallization into plantlike forms. A teacher: The trees didn’t exist? Dr. Steiner: No, they existed as tree forms. The entire flora of the coal age was not physically present. Imagine a forest present only in its etheric form and that thus resists the wind in a particular way. Through that, stalactite-like forms emerge. What resulted is not the remains of plants, but forms that arise simply due to the circumstances brought about by elemental activity. Those are not genuine remains. You cannot say it was like it was in Atlantis. There, things remained and to an extent also at the end of the Lemurian period, but as to the carbon period, we cannot say that there are any plant remains. There were only the remains of animals, but primarily animals that we can compare with the form of our head. A teacher: When did the human being then stand upright? I don’t see a firm point of time. Dr. Steiner: It is not a good idea to cling to these pictures too closely, since some races stood upright earlier and others later. It is not possible to give a specific time. That is how things are in reality. A teacher: If the pistil is related to the Moon and the stigma to the Sun, then how do they show the movement of the Sun and Moon? Dr. Steiner: You must imagine it in the following way (Dr. Steiner draws). The stigma goes upward, that would be the path of the Sun, and the pistil moves around it, and there you have the path of the Moon. Here we have the picture of the Sun and Earth path as I drew it yesterday. The Moon moves around the Earth. That is in the pistil (Dr. Steiner demonstrates with the drawing). It appears that way because the path of the Moon goes around also, of course, but in relationship, not in a straight line. The path of the Sun is the stigma. This circle is a copy of the helix I drew yesterday. It is also a helix.  A teacher: You have told us that the temperaments have to do with predominance of the various bodies. In GA 129, you said that the physical body predominates over the etheric, the etheric over the astral, and the I over the astral. Is there a connection with the temperaments here? In GA 134, you mention a figure that gives the proper relationship of the bodies. Dr. Steiner: That gives the relationship of the forces. A teacher: Is there a further relationship to the temperaments? Dr. Steiner: None other than what I presented in the seminar. A teacher: You have said that melancholy arises due to a predominance of the physical body. Is that a predominance of the physical body over the etheric? Dr. Steiner: No, it is a predominance over all the other bodies. A question arises about parent evenings. Dr. Steiner: We should have them, but it would be better if they were not too often, since otherwise the parents’ interest would lessen, and they would no longer come. We should arrange things so that the parents actually come. If we have such meetings too often, they would see them as burdensome. Particularly in regard to school activities, we should not do anything we cannot complete. We should undertake only those things that can really happen. I think it would be good to have three parent days per year. I would also suggest that we do this festively, that we print cards and send them to all of the parents. Perhaps we could arrange it so that the first such meeting is at the beginning of the school year. It would be more a courtesy, so that we can again make contact with the parents. Then we could have a parent evening in the middle of the year and again one at the end. These latter two would be more important, whereas the first, more of a courtesy. We could have the children recite something, do some eurythmy, and so forth. We can also have parent conferences. They would be good. You will probably find that the parents generally have little interest in them, except for the anthroposophical parents. A teacher asks Dr. Steiner to say something about the popularization of spiritual science, particularly in connection with the afternoon courses for the workers [at the Goetheanum]. Dr. Steiner: Well, it is important to keep the proper attitude in connection with that popularization. In general, I am not in favor of popularizing by making things trivial. In my opinion, we should first use Theosophy as a basis and attempt to determine from case to case what a particular audience understands easily, or only with difficulty. You will see that the last edition of Theosophy has a number of hints about how you can use its contents for teaching. I would then go on to discussing some sections of How to Know Higher Worlds, but I would never intend to try to make people into clairvoyants. We should only inform them about the clairvoyant path so that they understand how it is possible to arrive at those truths. We should leave them with the feeling that it is possible with normal common sense to understand and know about how to comprehend those things. You can also treat The Spiritual Guidance of the Individual and Humanity in a popular way. There you have three books that you can use for a popular presentation. Generally, you will need to arrange things according to the audience. Several children are discussed. Dr. Steiner: The most important thing is that there is always contact, that the teacher and students together form a true whole. That has happened in nearly all of the classes in a very beautiful and positive way. I am quite happy about what has happened. I can tell you that even though I may not be here, I will certainly think much about this school. It’s true, isn’t it, that we must all be permeated with the thoughts: First, of the seriousness of our undertaking. What we are now doing is tremendously important. Second, we need to comprehend our responsibility toward anthroposophy as well as the social movement. And, third, something that we as anthroposophists must particularly observe, namely, our responsibility toward the gods. Among the faculty, we must certainly carry within us the knowledge that we are not here for our own sakes, but to carry out the divine cosmic plan. We should always remember that when we do something, we are actually carrying out the intentions of the gods, that we are, in a certain sense, the means by which that streaming down from above will go out into the world. We dare not for one moment lose the feeling of the seriousness and dignity of our work. You should feel that dignity, that seriousness, that responsibility. I will approach you with such thoughts. We will meet one another through such thoughts. We should take that up as our feeling for today and, in that thought, part again for a time, but spiritually meet with one another to receive the strength for this truly great work. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Fourth Meeting

22 Dec 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Fourth Meeting

22 Dec 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

The teachers took turns providing afternoon child care. A teacher asks a question about what they should do with the children. Dr. Steiner: The children should enjoy themselves. You can allow them to play, or they could also put on a play or do their homework. In afterschool care, you should be a child yourself and make the children laugh. The children should do something other than their normal school activities. They only need to feel that someone is there when they need something. It is particularly valuable when the children tell of their experiences. You should interest yourselves in them. It is helpful for children when they can speak freely. You can also let them make pottery. A teacher: The faculty would like to have a school festival on the first Monday of each month, since that day is generally free in the Stuttgart area [no school on those days]. We have already had such festivals on November 3 and December 1. Dr. Steiner: It would be better to have monthly festivals on Thursday. Monday is a humdrum day, and there are inner reasons for favoring Thursdays. As Jupiter’s day, Thursday is most appropriate. The monthly festival should recall the significance of the month in a way similar to the Calendar of the Soul. But, we can use the verses from the Twelve Moods only for the seventh and eighth grades, at best. A teacher reports about teaching the first grade. Dr. Steiner: It is not good to draw with pencils. You should try to use watercolors, but crayons are also useful. The stories should not be too long. Short, precise and easily comprehended stories are preferable in the lower grades. The main thing is that what you tell remains with the children. You should make sure that the children do not immediately forget anything you go through with them. They should not learn through repetition, but remember things immediately through the first presentation. A teacher reports about the second grade. Dr. Steiner: You should begin with division right away. If some children are having difficulty with grammar, you should have patience. A teacher reports about her third grade. She has introduced voluntary arithmetic problems as a will exercise. Dr. Steiner: It is important to keep the children active. Their progress in foreign languages is very good; it has been very successful. The more we succeed in keeping the children active, the greater will be our success. I should also mention eurythmy in connection with foreign languages. Every vowel lies between two others; between “ah” and “ee” there lies the right hand forward and the left back. Do it according to the sound, not according to the letter. [German editor’s comment: From the perspective of eurythmy, Dr. Steiner may have meant the following: Every vowel lies between two others. For example, the English “i” lies between the German “a” (ah) and “i” (ee), with the gesture, the right hand forward, the left, back. Go according to how the vowel sounds, not according to how the letter is written.] A teacher speaks about the fourth grade. Dr. Steiner: They are particularly untalented. A.S. [a child] is a little feebleminded. She cannot pay attention. E.E., the Bolshevik, has gotten better. He has an abnormality in the meninges, that is, an abnormal development of the head and meninges. He has twitchy cramps. Perhaps that is due to an injury at birth because of the use of forceps [see sketch], or perhaps he inherited it. His etheric body is shut out. You should divert his fantasy through humor. G.R. has a different situation in regard to his supersensible aspects because he is missing a leg. In such crippled children, the life of the soul is too spiritual. You should awaken his interest for things spiritually difficult for the soul. Direct him there and bring back his soul qualities. A teacher speaks about the fifth grade. Dr. Steiner: The children love their teacher, but at the same time are terribly rambunctious. Try to be more independent of them. Also, in foreign languages, you should teach reading by way of writing. A teacher speaks about the sixth grade. Dr. Steiner: The children can better learn to think and feel through eurythmy and vice versa. You could allow A.B. to do some of the sentences contained in the teachers’ speech exercises in eurythmy. You will need to help E.H. by telling deeply moving stories. A teacher complains that the children in the upper classes are lazy and unmotivated. Dr. Steiner: If the children do not do their homework, you could keep the lazy ones after noon and threaten them that this could occur often. A teacher asks about some children in the seventh and eighth grades. Dr. Steiner: The children in the seventh and eighth grades are talented. G.L., the one with the blue ribbons, is very flirtatious. It is better not to name names, to turn around and not name her and not to watch. But you should be certain that she knows you mean her. Praise does not make the children ambitious. You may not omit praise and criticism. Criticism, given as a joke, is very effective. The child will remember it. A teacher speaks about eurythmy and music. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Fifth Meeting

23 Dec 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Fifth Meeting

23 Dec 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

A teacher who took over the seventh and eighth grades in the fall reports about teaching the humanities. Dr. Steiner: You should begin by developing an outline of Roman history and then, from the general character, go into the details. There is no particular reason to go into everything, for instance, the history of the Lucretians. In Rome, much more occurred than what has been handed down, and there is really no reason to tell about everything that has been handed down by chance. A teacher: Who were the Etruscans? Dr. Steiner: The Etruscans were a southern Celtic element, a branch of the Celts transplanted in the south. A teacher asks about books on Oriental history. Dr. Steiner: Well, there are the chapters about Babylonian and Assyrian history by Stahl and Hugo Winkler in Helmolt’s Weltgeschichte [World History], and also the things written by Friedrich Delitzsch, for example, his Geschichte Babyloniens und Assyriens (History of Babylonia and Assyria). A teacher: What is Baal? Dr. Steiner: Baal was originally a Sun god. A teacher speaks about the practical subjects in the seventh and eighth grades. A teacher reports about teaching Latin. Dr. Steiner: It would be good to direct the children’s attention away from the linguistic aspects and toward the meaning, toward the subject itself. There is too little personal contact with the students. A teacher reports about shop class. Dr. Steiner: We should learn what we want to teach, for example, how to bind books or to make shoes. We should not bring too much in from outside. On Friday, December 26 at 9:00 a.m., those children in the first through fourth grades who are causing the teachers difficulties in some ways are to be called in for a “discussion” and on Monday, December 29 at 9:00 a.m., there will be another such meeting for children from the fifth through eighth grades. A list is made of those children. Two teachers report about the independent religious instruction. Dr. Steiner: In the independent religious instruction, you could try to bring in something imaginative, mythical religious pictures, for example, the story of Mithras as a picture of how we overcome our lower nature. You could use such pictures to bring something to the fore, that is, to integrate mythical stories pictorially. A teacher asks about reports. Dr. Steiner: We must first determine what we have to do [to meet the state requirements]. We can give two reports, one in the middle of the year, as an interim report, and one at the end of the school year. To the extent allowable by the regulations, we should speak about the student only in general terms. We should describe the student and only when there is something of particular note in a subject, should we mention that. We should carefully formulate everything, so that in moving to the higher grades, there is as little differentiation as possible. When the student goes to another school, we must report everything that the new school requires. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Sixth Meeting

01 Jan 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Sixth Meeting

01 Jan 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Dr. Steiner: Today, we will primarily discuss the problem children we spoke with. We will need to look at M.H. often. We will have to ask E.S. many things. We can give some of the children in the fourth grade specific exercises, for instance, E.E. could learn the phrase, “People gain strength for life through learning.” You could allow him to say this each morning in the course of the first period. F.R. could learn, “I will pay attention to my words and thoughts,” and A.S. could learn, “I will pay attention to my words and deeds.” We should have H.A. in the fifth grade do complicated drawings, for instance, a line that snakes about and comes back to its own beginning. He could also draw eurythmy forms. He should learn the phrase, “It is written in my heart to learn to pay attention and to become industrious.” You will need to force T.E. in the seventh grade to follow very exactly and slowly. She should hear exactly and slowly what you say to her. That should have a different tempo than her own fragmented thinking. Think a sentence together with her, “I will think with you.” Only think it twice as slowly as she does. O.R., in eighth grade, is sleepy. He is a kind of soul-earthworm. That kind of sleepiness arises because people pass things by and pay no attention to them. He shouldn’t play any pranks on anyone, nor disturb anyone’s attention. In regard to the slow thinking in the third grade, you could take a phrase like, “The tree becomes green,” and turn it around to “Green becomes the tree,” and so forth so that they learn to turn their thinking around quickly. My general impression is that, in spite of all of the obstacles, you should maintain the courage to continue your teaching. Although there is not much time left in this year, we still have much to do. There is some discussion of afterschool care. Dr. Steiner: The children should avoid comparing their teachers. You should pay attention to the children’s physical symmetry and asymmetry and seek what lies parallel in their souls. To do that, you must know each child’s peculiarities well. There is something called “flame symmetry,” that is, how things interact through harmonious motions. Ellicot first noticed it and did some work with it. What the teacher thinks affects the child when the teacher is really present. The main thing is that you take an interest in each child. A teacher asks about how to get through all the material and about homework. Dr. Steiner: You should present homework as voluntary work, not as a requirement. In other words, “Who wants to do this?” A teacher asks about a reading book. Dr. Steiner: In the reading lesson, not all of the children need to read. You can bring some material and hand it around, allowing the children to read it, but not all need do so. However, the children should read as little as possible about things they do not understand very well. The teachers are reading aloud to the children too much. You should read nothing to the children that you do not know right into each word through your preparation. A teacher asks about modeling. Dr. Steiner: You could use a column seen from a particular perspective as an example, but you should not make the children slavishly imitate it. You need to get the children to observe, but allow them to change their work. A teacher: How far should I go in history before turning to something else? In the seventh grade, I have gotten as far as the end of the Caesars in Roman history, and in the eighth grade, I am at the Punic Wars. Dr. Steiner: Make an effort to get to Christianity and then do two months of German. Do Goethe and Schiller in the eighth grade. [Dr. Steiner tells an anecdote about a child who is asked, “Who are Goethe and Schiller?” The child replies, “Oh, those are the two statues sitting on the piano at home.”] You should teach German history differently in the eighth grade than in the seventh. A teacher asks a question. Dr. Steiner: The teachers should write essays for The Social Future. They should tell about their pedagogical experiences, in particular, of the children’s feelings. Modern pedagogical literature is absolutely worthless before Dittes. However, through such writings, we can make it more human. A teacher: Should we form a ninth grade next year? Dr. Steiner: A ninth grade is certainly desirable. The school regulations no longer apply then, and we can be quite free. The ninth grade will arise spontaneously out of the results of the eighth grade. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Seventh Meeting

06 Mar 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Seventh Meeting

06 Mar 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Mr. Oehlschlegel was in America and his teaching responsibilities had to be divided among the others. Dr. Steiner: Dr. Kolisko will take over the main lesson in the sixth grade. Mr. Hahn will take over the advanced classes in independent religious instruction. Since, with the language classes in the third and fifth grades, he will have a total of twenty-five hours, he needs some relief. Eighteen hours would be a normal amount. Miss Lang will take over the English and French classes for her third grade. In the fifth grade, Dr. von Heydebrand will teach French, and Dr. Kolisko, English. Mrs. Koegel will take over English for her fourth grade and Dr. Kolisko, the remaining English instruction until summer vacation. Questions are asked regarding how to arrange the Sunday services and the music in them. Dr. Steiner: The Sunday services are only for those children taking the independent religious instruction. They offer a replacement for the children and parents who are not members of any church. The services should close with something musical, in particular, something instrumental. We should offer refreshments for invited guests only when I am here. A teacher reports about a student in the fifth grade who left the independent religious instruction and returned to the Catholic instruction. Dr. Steiner: We should avoid allowing the children to leave the independent religious instruction. However, we will need to accept that the minister giving the Lutheran instruction is leaving. A question is asked about the eurythmy instruction. Dr. Steiner: Eurythmy is obligatory. The children must participate. Those who do not participate in eurythmy will be removed from the school. We can form a eurythmy faculty that will take care of advertising eurythmy and the eurythmy courses for people outside the school. A teacher: Should the gardening class continue to be voluntary? Dr. Steiner: The gardening class is an obligatory part of the education. A teacher asks a question. Dr. Steiner: The general rule at the school is that those children with many unexcused absences will be removed from the school. A teacher complains about the presentation of ethics. Dr. Steiner: We shouldn’t teach anything abstract, but teach the children respect. The children should not raise their hands so much. We will have to allow the state medical examinations. A teacher: Should we set up a continuing education school for those children graduating from the eighth grade at Easter? Dr. Steiner: We could call it a “School of Life for Older Children,” and we could call the kindergarten, “preschool.” |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Eighth Meeting

08 Mar 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Eighth Meeting

08 Mar 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Dr. Steiner: We still have four months ahead of us after having finished five. A teacher reports about mathematics and science instruction in the seventh and eighth grades. Dr. Steiner: In eighth grade optics, you should teach only about refraction (lenses) and the spectrum. In teaching thermodynamics, teach only melting (thermometer), boiling, and the sources of heat. Then go into magnetism only briefly. In electricity, you will need to teach about static electricity. In mechanics, the lever and incline plane; and in aerodynamics, the lifting forces and air pressure. In chemistry, you should cover burning and how substances combine and separate. In the seventh grade, you should discuss optics and magnetism in more detail than in the eighth grade. You also need to cover the mechanics of solid bodies. A teacher reports about the humanities in the seventh and eighth grades. There is a discussion about Goethe’s biography and also his Poetry and Truth, as well as Schiller’s Aesthetic Letters. Dr. Steiner: I would recommend Herder’s Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit [Thoughts on the philosophy of human history], in which he presents the human being as a summation of all the other natural realms. World History should continue right up until the present. A teacher speaks about the sixth grade. A teacher speaks about the fifth grade. Much of the subject matter has not yet been taught. Dr. Steiner: It is better to omit some material than to hurry. In teaching about human beings and animals, you should discuss the brain, the senses, the nerves, the muscles, and so forth. A teacher asks about Latin letters and German grammar in the fourth grade. Dr. Steiner: If you are to teach Latin handwriting, it is perhaps better to first develop German handwriting out of drawings and then develop characteristic Latin letters from the drawings. You can create sentences from poems, but do it in a kind way, don’t do it pedantically. Two teachers speak about the second and third grades. A teacher speaks about the first grade. E.S. has not returned since being deloused. Another question is asked regarding how to introduce letters. Dr. Steiner: It would be best to first create the forms of the letters pictorially, and then to gradually move into the letters themselves. In general, you should concentrate. A teacher reports about music and eurythmy, also tone eurythmy. Dr. Steiner: We could send a flyer about the school regulations to all the parents every four weeks saying that eurythmy is a required class. A teacher reports about foreign language instruction. Dr. Steiner: In Latin, and in the languages generally, you should not have the children translate, but only freely speak about the content, about the meaning, so that you can see that they have understood. Otherwise, you would adversely affect the meaning of language. In the upper grades, you will also need to teach the children something about the vowel shifts, thus coming back to the standpoint of English. You should always pay strict attention that you teach the class, not just individuals. If one child occupies you for a longer period, then you should now and then ask questions of the others to keep them awake. Treat the class like a chorus. A teacher reports about the instruction in social understanding. Dr. Steiner: In the seventh and eighth grades, you could give them what is in Towards Social Renewal. A teacher asks about the emotionally disturbed children. Dr. Steiner: The remedial class is for those who have significant learning barriers. Those children are not in the normal class, and Dr. Schubert teaches them separately every day during that time. A.B. has a strong tendency toward dementia praecox. E.G. is disturbingly restless. You must often reprimand him, as otherwise he could develop dementia praecox by the age of fifteen. We have seven or eight children like that in the school. A teacher reports about a student who stole something. Dr. Steiner: With children who steal, it is good to have them remember scenes they experienced earlier. You should have them imagine things they experienced years before, for instance, with seven-year-olds, experiences they had when they were five, or with ten-year-olds, experiences they had when they were seven. You should also have them recall experiences from two weeks before. Things will then become better quickly. If you do nothing, these problems will become larger and develop into kleptomania. In such cases, things that solidify the will are particularly effective, and recalling things that go back weeks, months, or years is particularly effective in firming the will. In cases of kleptomania, it is also good to punish the children by having them sit for a quarter of an hour and hold their feet or toes with their hands. From the perspective of strengthening the will, that is something you can do against kleptomania. There are also children who cannot remember, who on the next day can no longer remember what they did the day before. In that case, you must strengthen their capacity to remember by having them recall things in reverse order. You still have the children say those phrases I once gave you as prayers for them, don’t you? “People gain strength for life through learning,” “I will pay attention to my thoughts and deeds” or “… and words.” You can hardly strengthen memory other than by attempting to have the children imagine something backward, for instance, “the father reads in the book,” turned around to, “book the in reads father the,” so that they have a pictorial image of that. Or you can have them say the numbers 4, 6, 7, 3 in reverse order, 3, 7, 6, 4. Or perhaps the hardness scale, back and forth. You also do not need to shy away from having the children repeat little poems that they have said word for word backward. They can also say the speech exercise backward. That is a technique you can use when memory is so weak. There is some discussion about the scientific work done in the research institute. Dr. Steiner: You should not dissipate your strengths. You should have friendly and neighborly relations with Dr. Rudolf Maier’s research institute. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Ninth Meeting

14 Mar 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Ninth Meeting

14 Mar 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

There are complaints about the lack of discipline in the school. Dr. Steiner: Mr. Baumann will give a class once a week about tact and morality, about essential tact and living habits, so that the children will realize that one thing is acceptable and another is misbehavior. The children’s thoughts should evoke a feeling for authority. That class will not be connected with the other instruction, but included in the afternoon classes. There is further discussion about stealing. Dr. Steiner: If we pay too much attention to individuals, that will undermine all discipline. In my opinion, with regard to stealing, we should not need to look at individual cases. We should, instead, arrange things so that the children avoid it. A teacher: Should we arrange an Easter festival or a Festival for Youth for the children without a religious confession? Perhaps a spring festival? Dr. Steiner: We can include the independent religious instruction students of the four upper grades in the celebration. [German editor’s comment: The discussion here is not about the present Celebration for Youth, which was first initiated by Dr. Steiner at Easter in 1921.] Dr. Steiner: It would be good to put the boys and girls together. A teacher asks about the class for the emotionally disturbed children. Dr. Steiner: We will include about ten children in the class for emotionally disturbed children that Dr. Schubert will give. The children to be included in this class are discussed. The children A.S. and A.B. are mentioned several times. Dr. Steiner: You will have to work with the children individually in this class. There is not much else that will be different, except that you will have to do everything more slowly. A teacher: Should we have the children study Goethe’s “Heathrose”? It seems too erotic. Dr. Steiner: “Heathrose” is not an erotic poem, but “I went into the forest …” certainly is. A teacher: What should we do with the children in the continuation school? Dr. Steiner: The main thing would be to concentrate upon practical and artistic subjects. The children should learn about practical things in life, about agriculture, commerce, industry, and trade. They should learn about the basic principles of business and accounting, and also continue their artistic, musical, and literature studies. Mr. Strakosch will take over that task. The children must learn to consider life as a school. You can remind them that from now on they will be taught by life. However, we should not rob them of their destiny. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Tenth Meeting

09 Jun 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Tenth Meeting

09 Jun 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Dr. Steiner: The teachers will understand their students better because each teacher will remain with his or her class. We must continue to work in this direction and use those things we discussed in the teachers’ seminar. When you can properly judge a child’s temperament, everything will come of itself. You should work toward reflecting the child’s temperament in the sound of your voice when you call the child. The year-end report and a brochure are discussed. Dr. Steiner: We should include something about the layout and plan of the school, as well as the curriculum, in the yearly report. We should also include something about the students and where they came from: 161 from elementary schools, 50 from middle schools, 64 from secondary schools, 12 beginning students—altogether, 287. And we should say something about the students’ religious affiliations. Include something about the many volumes in the teachers’ library. Also, the collections and displays, but we should not discuss the individual collections, only provide a summary. Mention the students’ library, also. Say something about eurythmy as a new subject. I would ask Mr. Baumann to report about that. We can also include something about handwork classes, perhaps including some remarks about the lack of industriousness. However, we should emphasize what is of lasting value. The history of the school year should receive special treatment. Begin with the brochure. Later, however, we will replace the brochure with a report by a faculty member. For the present, we can simply include the brochure. Each of you who wants to can write an autobiography to include in the yearly report. We should also have a description of each teacher, for example, what the teacher did before becoming a teacher. We can also include eulogies for those who died in the past year. Often, we bring out things too strongly that belong behind the scenes. A teacher remarks that Dr. Steiner’s leadership of the school should be emphasized. Dr. Steiner: You can mention my courses and lectures as well as those that the teachers have given. We should also say something about the lecture series sponsored by the Waldorf-Astoria factory, although those lectures have less connection with the school than with the adult education school. Give a history of that school along with a list of lectures the teachers have held there. In fact, we should say something about the general educational activities at the factory. Mention also the activities and lectures by the teachers in the independent apprenticeship school, as well as the courses for social understanding given for young people. Say something about the archive also. We need to have a separate section about the preparatory instruction for the Youth Festival. Actually, we need to discuss the activities of the Lutheran, Catholic and independent religious classes, but if we cannot have a special section for each of the religions, we should leave it out. All the classes were then discussed. All the teachers gave a report about what they did in the course of the school year, how far they came, and what the state of the class was. First, two teachers spoke about the main lessons in the first and second grades, and then a teacher spoke of the main lesson and foreign language in the third grade. Dr. Steiner: In the foreign languages, you should not rely upon a dictionary and should not translate. You should also avoid giving the children the text in German. The best thing is to read the foreign language text first, and then to tell the children the content in your own words. There is so much dust on the desks and dirt in the classrooms! The teachers should collect information about psychological aspects, sort of an almanac about psychological abnormalities. It would be an almanac in a broad sense. From a spiritual scientific perspective, these things are quite obvious. You can talk about them, since many things have actually occurred. Something interesting occurred today in the eighth grade. What was the boy’s name? He writes exactly like you do, Dr. Stein. He imitates your handwriting exactly. That is certainly an interesting thing. If someone has straight hair, he will learn the handwriting of the teachers. A child with curly hair would not have done that. A teacher reports about the fourth grade. The children did not know anything about grammar, asking what it was. Dr. Steiner: It would be good if, at the end of the main lesson, you had the children remember in reverse order everything they did that morning. A teacher: What did you mean by the psychological “almanac”? Dr. Steiner: It would be a collection for the faculty, and could be very important. You could include all kinds of interesting things. If you think about it, you can immediately find a barrelful of such things. Each teacher can take note of all the things observed. For the higher grades, you should provide information about what the children did not know when they came to us. You should describe the things the children were missing. If you could put that together for the first yearly report, I would be very grateful. That the children asked, for instance, “What is German grammar?” is culturally significant. You should record observations of the children who entered the Waldorf School. You should note what the children forgot and what kinds of misbehavior they had. Then include things about the instruction. At the end of the collection, we could state that it is obvious that we did not completely realize our intentions with each of the grades in the course of the year, but only generally. Two teachers report about the fifth and sixth grades. Dr. Steiner: The children in the sixth grade write unbelievably horribly. They are really happy when they can write “lucky” with two “k”s. It is more important that they can write business letters and learn algebra than that they can spell “lucky” with two “k”s. A teacher reports about the humanities in the seventh and eighth grades. It is difficult to complete the material for history. The children don’t know anything more than what they learned in religion class. Dr. Steiner: In 1890, I went to the Goethe Archive in Weimar. The director, Mr. Suphan, had two boys and one of my tasks was to teach them. In that way, I gained some insight into the schools in Berlin. I have to admit that although history was well taught in Austria, you couldn’t detect that those children had learned any of it in Germany. Their textbooks contained nothing about it. There were thirty pages of introductory information from Adam to the Hohenzollern, then the history of the Hohenzollerns began. That is true of all Germany; there is really nothing appropriate in middle school history classes. A teacher asks about Allah. Dr. Steiner: It is difficult to describe that supersensible being. Mohammedism is the first manifestation of Ahriman, the first Ahrimanic revelation following the Mystery of Golgotha. Mohammed’s god, Allah, Eloha, is an Ahrimanic imitation or pale reflection of the Elohim, but comprehended monotheistically. Mohammed always refers to them as a unity. The Mohammedan culture is Ahrimanic, but the Islamic attitude is Luciferic. A teacher: In the Templar records, a being by the name of Bafomet appears often. What is that? Dr. Steiner: Bafomet is a being of the Ahrimanic world who appears to people when they are being tortured. That happens really cleverly, since they then bring a lot of visions back with them when they return to consciousness. In 869 A.D., there was the Filioque Argument. History books say nothing about this, but you can read about it in Harnak’s “Dogmengeschichte” (History of dogma). A teacher asks a question. Dr. Steiner: The Catholic religious instruction is much further ahead, the Lutheran, very limited. Compared to other biographies, the one on Goethe by the Jesuit priest Baumgartner is quite well written, though he complains a lot. Everything else is simply rubbish. The biography of Goethe by the Englishman Lewes is poor. Swiss folk calendar. A teacher reports about the instruction in natural sciences in the 7th and eighth grades. Dr. Steiner: You can interrupt the natural science instruction at any point. The meeting continued on Saturday, June 12, 1920 at 3:00 p.m. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Eleventh Meeting

12 Jun 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Eleventh Meeting

12 Jun 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

A brochure and yearly report are mentioned. Dr. Steiner: What is the purpose of all this advertising? A teacher: We are going to send it to all interested people. Dr. Steiner: Then, is it an invitation? In that case, everything you have shown me is much too long. It will not be effective. If you want every potential member of the Waldorf School Association to read it, you should condense it into half a page. What you have here is a small book. A teacher: I don’t think it is so thick. Dr. Steiner: Think about Dr. Stein’s manuscript. It’s already thirty printed pages. It is too long and too academic. It’s more like a report to another faculty. It is directed more to pedagogical experts than to people who might want to join the Association. You should direct it to everyone interested in the school. They would never read so much. You did not mention this perspective last time. We always looked at the brochure from the standpoint of public relations. This brochure could serve only to replace the usual academic presentation. There have always been formal presentations and something like this could provide a general presentation of the school. We could, for instance, describe the facilities and buildings and then go on to describe the pedagogy of the school and the individual subjects. A teacher: We especially need material for the parents who want to send their children to us. Dr. Steiner: That’s true. For such parents, we could summarize all the material we already have. For example, there is some good material in the Waldorf News. None of that, however, can replace a brochure that should be no longer than eight printed pages. There should be thousands of members, and we need to give them a short summary. A teacher: That would not preclude also having a yearly report. Dr. Steiner: You must remember how little interest people have in things. Today, people read in a peculiar way. It’s true, isn’t it, that a magazine article is different. However, if you want to make something clear to someone and hope they will become a member and pay fifty marks, you don’t need to go into all the details. You need only give a broad outline. This brochure would be different. It would contain a request for payment of some amount. But, the yearly report might be more like what I would call a history of the school. There, we can include everything individual teachers put together. The reports need not be short. All reports can be long. If the brochure brings in a lot of money, Mr. Molt will surely provide some for the yearly report. All that is a question of republicanism. The number of names it mentions would make the yearly report effective. We should, however, consider whether we should strive for uniformity. One person may write pedantically and report about what happened each month. Another might write, at least from what I have seen, about things I could do only in five hundred years. (Speaking to Dr. Stein) You wrote this so quickly that you could also write the others. Dr. Steiner is asked to write something also. Dr. Steiner: That is rather difficult. If I were to write even three pages, I would have to report about things I have experienced, and that could be unpleasant for some. If I were to write it as a teacher, I would tend to write it differently than the brochure. The brochure should contain our intent, what we will improve each year. In the report, we should show what we accomplished and what we did not accomplish. There, the difference between reality and the brochure would be apparent. If I wrote something, I would, of course, keep it in that vein. It will put people out of shape afterward, but I can write the three pages. A teacher reports about his remedial class with nine children. Two teachers report about teaching foreign language in the first grade. Dr. Steiner: The earlier you begin, the more easily children learn foreign languages and the better their pronunciation. Beginning at seven, the ability to learn languages decreases with age. Thus, we must begin early. Speaking in chorus is good, since language is a social element. It is always easier to speak in chorus than individually. Two teachers report about the classes in Latin and Greek. There are two classes for Latin, but in the lower class, there are only two boys. The upper class is talented and industrious. Dr. Steiner: There is good progress in the foreign languages. A teacher reports about the kindergarten with thirty-three children. She asks if the children should do cut work in the kindergarten. Dr. Steiner: If you undertake such artistic activities with the children, you will notice that some have talent for them. There will not be many, and the others you will have to push. Those things, when they are pretty, are pretty. They are little works of art. I would allow a child to work in that way only if I saw that he or she has a tendency in that direction. I would not introduce it to the children in general. You should begin painting with watercolors. You mean cutting things out and pasting them? If you see that one or another child has a talent for silhouettes, you could allow that. I would not fool around, don’t do that. You can probably work best with the children you have when you have them do meaningful things with simple objects. Anything! You should try to discover what interests the children. There are children, particularly girls, who can make a doll out of any handkerchief. The doll’s write letters and then pass them on. You could be the postman or the post office. Do sensible things with simple objects. When the change of teeth begins, the children enter the stage when they want to imagine things, for instance that one thing is a rabbit and another is a dog. Sensible things that the child dreams into. The principle of play is that until the change of teeth, the child imitates sensible things, dolls and puppets. With boys, it is puppets, with girls, dolls. Perhaps they could have a large puppet with a small one alongside. These need only be a couple pieces of wood. At age seven, you can bring the children into a circle or ring, and they can imagine something. Two could be a house, and the others go around and live in it. In that game, the children are there themselves. With musical children, you can play something else, perhaps something that would support their musical talent. You should help unmusical children develop their musical capacities through dance and eurythmy. You need to be inventive. You can do all these things, but you need to be inventive, because otherwise everything becomes stereotyped. Later, it is easier because you can connect with things in the school. A teacher explains how she conveyed the consonants in eurythmy by working with the growth of plants. Dr. Steiner: That is very nice. The children do not differ much. You do not have many who are untalented nor many who are gifted. They are average children. Also, you have few choleric or strongly melancholic temperaments. Those children are mostly phlegmatic or sanguine. All that plays a role since you do not have all four temperaments. You can get the phlegmatic children moving only if you try to work with the more difficult consonants. For the sanguine children, work with the easier consonants. Do the r and s with the phlegmatic children, and with the sanguine children, do the consonants that only hint of movement, d and t. If we have other temperaments in the next years, we can try more things. It is curious that those children who do not accomplish much in the classroom can do a great deal in eurythmy. The progress is good, but I would like to see you take more notice of what progresses. Our task is to see that we speak more to the children about what we bring from the teaching material, that we look more toward training thinking and feeling. For example, in arithmetic we should make clear to the students that with minus five, they have five less than they owe to someone. You need to speak with them very precisely. It is often good to drift off the subject. You then notice that the children are not so perfect in their essays. It’s true, isn’t it, that the children who are more talented in their heads write good essays, and those who are more talented in their bodies are good in eurythmy. You should try to balance that through conversation. When you talk with children, if you speak about something practical and go into it deeply, you turn their attention away from the head. A teacher asks how to handle the present perfect tense. Dr. Steiner: I would speak with the children about various parallels between the past and the complete. What is a perfect person, a perfect table? I would speak about the connections between what is complete and finished and the perfect present tense. Then I would discuss the imperfect tense where you still are in the process of completion. If I had had time today, I would have gone through the children’s reading material in the present perfect. Of course, you can’t translate every sentence that way, but that would bring some life into it. Eurythmy also brings life into the development of the head. There is much you can do between the lines. I already said today that I can understand how you might not like to drift off the subject. That is something we can consider an ideal, namely to bring other things in. For example, today I wanted to tease your children in the third grade with “hurtig toch.” In that way, you could expand their thinking. That means “express train.” That is what I mean by doing things with children between the lines. The eurythmy room is discussed. Dr. Steiner: I was never lucky enough that someone promised that room to me. Frau Steiner would prefer to have simply the field and a roof above it. Although you can awaken the most beautiful physical capacities in children through eurythmy, they can also feel all the terrible effects of the room, and that makes them so tired. We all know of the beautiful eurythmy hall, but someone forgot to make the ventilation large enough, so that we can’t use it. For eurythmy, we need a large, well-ventilated hall. Everything we have had until now is unsatisfactory for a eurythmy hall. We have only a substitute. Eurythmy rooms need particularly good ventilation. We have to build the Eurythmeum. |

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Twelfth Meeting

14 Jun 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 300a. Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner I: Twelfth Meeting

14 Jun 1920, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Pusch, Gertrude Teutsch Rudolf Steiner |

|---|