| 225. Cultural Phenomena — Three Perspectives of Anthroposophy: Cultural Phenomena

01 Jul 1923, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| But Albert Schweitzer says quite correctly at a later point in his writing: “Kant and Hegel ruled millions who never read a line of theirs and did not even know that they obeyed them.” |

| And there is hardly a single one of you whose thinking does not involve Kant and Hegel, because the paths are, I would say, mysterious. And if people in the most remote mountain villages have come to read newspapers, it also applies to them, to these people in the mountain villages, that they are dominated by Kant and Hegel, not only to this illustrious and enlightened society sitting here in the hall. |

| A newspaper article begins by saying how ineffective Bergson seems in comparison to Kant. But then it goes on to say: Steiner's wild speculations and great spiritual tirades stand even less up to an epistemological test based on Kant. |

| 225. Cultural Phenomena — Three Perspectives of Anthroposophy: Cultural Phenomena

01 Jul 1923, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Today's lecture is intended to be just one episode in the series of lectures I have given, an insertion, in fact, for the reason that it is necessary for anthroposophists to be alert people, that is, to form an opinion by looking at the world in a certain way. And so it is necessary from time to time to insert one or other of these into lectures that otherwise deal with anthroposophical material, in order to open up a view of the other events, of the other state of our civilization. And today I would like to expand on what I briefly mentioned in the last article in the “Goetheanum”, where I talked about a publication that has just been released: “Decay and Rebuilding of Culture” by Albert Schweitzer. It describes itself as the first part of a philosophy of culture and is essentially concerned with a kind of critique of contemporary culture. However, in order to support some of the characteristics that Albert Schweitzer gives of the present, I would like to start by presenting the existence of the culture that Albert Schweitzer wants to address through a single, but perhaps characteristic example. I could have chosen thousands. You can only pick and choose from the full cultural life of the present, but rather from the full cultural death of the present, and you will always find enough. That is precisely the point, as I also noted in the pedagogical lectures yesterday and today, that we are getting used to looking at such things with an honestly alert eye. And so, to establish a kind of foundation, I have selected something from the series that can always be considered a representation of contemporary intellectual culture. I have chosen a rector's speech that was delivered in Berlin on October 15, 1910. I chose this speech because it was given by a medical doctor, a person who is not one-sidedly immersed in some kind of philosophical cultural observation, but who, from a scientific point of view, wanted to give a kind of contemporary tableau. Now I do not want to trouble you with the first part of this rectorate speech, which is mainly about the Berlin University, but I would like to familiarize you more with the general world view that the physician Rubner – because that is who it is – expressed on a solemn occasion at the time. It is perhaps a characteristic example because it dates back to 1910, when everyone in Europe and far beyond was optimistically convinced that there was a tremendous intellectual upturn and that great things had been achieved. The passage I want to select is a kind of apostrophe to the student body, but one that allows us to see into the heart of a representative figure of the present age and understand what is really going on there. First of all, the student body is addressed as follows: “We all have to learn. We bring nothing into the world but our instrument for intellectual work, a blank page, the brain, differently predisposed, differently capable of development; we receive everything from the outside world.” Well, if you have gone through this materialistic culture of the present day, you can indeed have this view. There is no need to be narrow-minded. You have to be clear about the power that materialistic culture exerts on contemporary personalities, and then you can understand when someone says that you come into the world with a blank sheet, the brain, and that you receive everything from the outside world. But let us continue to listen to what this address to students has to say. It begins by explaining, apparently somewhat more clearly, how we are a blank slate, how the child of the most important mathematician must learn the multiplication table again, because, unfortunately, he has not inherited advanced mathematics from his father, how the child of the greatest linguist must learn his mother tongue again, and so on. No brain can grasp everything that its ancestors have experienced and learned. But now these brains are being advised what they, as completely blank slates, should do in the world in order to be written on. It goes on to say: “What billions of brains have considered and matured in the course of human history, what our spiritual heroes have helped create...” — not true, that is said for two pages in a row, it is inculcated into people: they are born with their brains as a blank slate and should just be careful to absorb what the spiritual heroes have created. Yes, if these intellectual heroes were all blank slates, where did it all come from, what they created, and what the other blank slates are supposed to absorb? A strange train of thought, isn't it! - So: “What our spiritual heroes have helped to create is received” by this blank sheet of brain “in short sentences through education, and from this its uniqueness and individual life can now unfold.” On the next page, these blank pages, these brains, are now presented with a strange sentence: “What has been learned provides the basic material for productive thinking.” So now, all at once, productive thinking appears on the blank pages, these brains. It would be natural, though, for someone who speaks of brains as blank pages not to speak of productive thinking. Now a sentence that shows quite clearly how solidly materialistic the best of them gradually came to think. For Rubner is not one of the worst. He is a physician and has even read the philosopher Zeller, which is saying something. So he is not narrow-minded at all, you see. But how does he think? He wants to present the refreshing side of life, so he says: “But there is always something refreshing about working in a new, previously untilled field of the brain.” So when a student has studied something for a while and now moves on to a different subject, it means that he is now tilling a new field of the brain. As you can see, the thought patterns have gradually taken on a very characteristic materialistic note. “Because,” he continues, “some fields of the brain only yield results when they are repeatedly plowed, but eventually bear the same good fruit as others that open up more effortlessly.” It is extremely difficult to follow this train of thought, because the brain is supposed to be a blank slate, and now it is supposed to learn everything from the written pages, which must also have been blank when they were born. Now this brain is supposed to be plowed. But now at least one farmer should be there. The more one would go into such completely incredible, impossible thinking, the more confused one would become. But Max Rubner is very concerned about his students, and so he advises them to work the brain properly. So they should work the brain. Now he cannot help but say that thinking works the brain. But now he wants to recommend thinking. His materialistic way of thinking strikes him in the neck again, and then he comes up with an extraordinarily pretty sentence: “Thinking strengthens the brain, the latter increases in performance through exercise just like any other organ, like our muscle strength through work and sport. Studying is brain sport. Well, now the Berlin students in 1910 knew what to think: “Thinking is brain sport.” Yes, it does not occur to the representative personality of the present what is much more interesting in sport than what is happening externally. What is actually going on in the limbs of the human being during the various sporting movements, what inner processes are taking place, would be much more interesting to consider in sport. Then one would even come across something very interesting. If one were to consider this interesting aspect of sport, one would come to the conclusion that sport is one of those activities that belong to the human being with limbs, the human being with a metabolism. Thinking belongs to the nervous-sensory human being. There the relationship is reversed. What is turned inward in the human being, the processes within the human being, come to the outside in thinking. And what comes to the outside in sport comes to the inside. So one would have to consider the more interesting thing in thinking. But the representative personality has simply forgotten how to think, cannot bring any thought to an end at all. Our entire modern culture has emerged from such thinking, which is actually incomplete in itself and always remains incomplete. You only catch a glimpse of the thinking that has produced our culture on such representative occasions. You catch it, as it were. But unfortunately, those who make such discoveries are not all that common. Because in a Berlin rectorate speech, a university speech on a festive occasion: “Our goals for the future” - if you are a real person of the present, you are taken seriously. That's what science says, that's what the invincible authority of science says, it knows everything. And if it is proven that thinking is brain sport, well, then you just have to accept it; then after millennia and millennia, people have become so clever that they have finally come to the conclusion that thinking is brain sport. I could continue these reflections now into the most diverse areas, and we would see everywhere that I cannot say the same spirit, that the same evil spirit prevails, but that it is naturally admired. Well, some insightful people saw what had become of it even before the outwardly visible decline occurred. And one must say, for example: Albert Schweitzer, the excellent author of the book “History of Life-Jesus Research, from Reimarus to Wrede,” who, after all, was able to advance in life-Jesus research to the apocalyptic through careful, thorough, penetrating and sharp thinking, could be trusted to also get a clear view of the symptoms of decay in contemporary culture. Now he assured us that this writing of his, “Decay and Rebuilding of Culture,” was not written after the war, but that the first draft was conceived as early as 1900, and that it was then elaborated from 1914 to 1917. Now it has been published. And it must be said that here is someone who sees the decline of culture with open eyes. And it is interesting to visualize what such an observer of the decline of culture has to say about what has been wrought on this culture, as if with sharp critical knives. The phrases with which contemporary culture is characterized come across like cutting knives. Let us let a few of these phrases sink in. The first sentence of the book is: “We are in the throes of the decline of culture. The war did not create this situation. It is only one manifestation of it. What was given spiritually has been transformed into facts, which in turn now have a deteriorating effect on the spiritual in every respect.” - “We lost our culture because there was no reflection on culture among us.” — “So we crossed the threshold of the century with unshakable illusions about ourselves.” — “Now it is obvious to everyone that the self-destruction of culture is underway.” Albert Schweitzer also sees it in his own way – I would say, somewhat forcefully – that this decline of culture began around the middle of the 19th century, around that middle of the 19th century that I have so often referred to here as an important point in time that must be considered if one wants to understand the present in some kind of awareness. Schweitzer says about this: “But around the middle of the 19th century, this confrontation between ethical ideals of reason and reality began to decline. In the course of the following decades, it came more and more to a standstill. The abdication of culture took place without a fight and without a sound. Its thoughts lagged behind the times, as if they were too exhausted to keep pace with it.” - And Schweitzer brings up something else that is actually surprising, but which we can understand well because it has been discussed here often in a much deeper sense than Schweitzer is able to present. He is clear about one thing: in earlier times there was a total worldview. All phenomena of life, from the stone below to the highest human ideals, were a totality of life. In this totality of life, the divine-spiritual being was at work. If one wanted to know how the laws of nature work in nature, one turned to the divine-spiritual being. If one wanted to know how the moral laws worked, how religious impulses worked, one turned to the divine-spiritual being. There was a total world view that had anchored morality in objectivity just as the laws of nature are anchored in objectivity. The last world view that emerged and still had some knowledge of such a total world view was the Enlightenment, which wanted to get everything out of the intellect, but which still brought the moral world into a certain inner connection with what the natural world is. Consider how often I have said it here: If someone today honestly believes in the laws of nature as they are presented, they can only believe in a beginning of the world, similar to how the Kant-Laplacean theory presents it, and an end of the world, as it will one day be in the heat death. But then one must imagine that all moral ideals have been boiled out of the swirling particles of the cosmic fog, which have gradually coalesced into crystals and organisms and finally into humans, and out of humans the idealistic ethical view swirls. But these ethical ideals, being only illusions, born out of the swirling atoms of man, will have vanished when the earth has disappeared in heat death. That is to say, a world view has emerged that refers only to the natural and has not anchored moral ideals in it. And only because the man of the present is dishonest and does not admit it to himself, does not want to look at these facts, does he believe that the moral ideals are still somehow anchored. But anyone who believes in today's natural science and is honest must not believe in the eternity of moral ideals. He does it out of cowardly dishonesty if he does. We must look into the present with this seriousness. And Albert Schweitzer also sees this in his own way, and he seeks to find out where the blame lies for this state of affairs. He says: “The decisive factor was the failure of philosophy.” Now one can have one's own particular thoughts about this matter. One can believe that philosophers are the hermits of the world, that other people have nothing to do with philosophers. But Albert Schweitzer says quite correctly at a later point in his writing: “Kant and Hegel ruled millions who never read a line of theirs and did not even know that they obeyed them.” The paths that the world's thoughts take are not at all as one usually imagines. I know very well, because I have often experienced it, that until the end of the 19th century the most important works of Hegel lay in the libraries and were not even cut open. They were not studied. But the few copies that were studied by a few have passed into the whole of educational life. And there is hardly a single one of you whose thinking does not involve Kant and Hegel, because the paths are, I would say, mysterious. And if people in the most remote mountain villages have come to read newspapers, it also applies to them, to these people in the mountain villages, that they are dominated by Kant and Hegel, not only to this illustrious and enlightened society sitting here in the hall. So you can say, like Albert Schweitzer: “The decisive factor was the failure of philosophy.” In the 18th and early 19th centuries, philosophy was the leader of public opinion. She had dealt with the questions that arose for people and the time, and kept a reflection on them alive in the sense of culture. In philosophy at that time, there was an elementary philosophizing about man, society, people, humanity and culture, which naturally produced a lively popular philosophy that often dominated opinion and maintained cultural enthusiasm. And now Albert Schweitzer comments on the further progress: “It was not clear to philosophy that the energy of the cultural ideas entrusted to it was beginning to be questioned. At the end of one of the most outstanding works on the history of philosophy published at the end of the 19th century, the same work that I once criticized in a public lecture, this work on the history of philosophy, “this is defined as the process in which,” and now he quotes the other historian of philosophy, ”with ever clearer and more certain consciousness, the reflection on cultural values has taken place, the universality of which is the subject of philosophy itself.” Schweitzer now says: “In doing so, the author forgot the essential point: that in the past, philosophy not only reflected on cultural values, but also allowed them to emerge as active ideas in public opinion, whereas from the second half of the 19th century onwards they increasingly became a guarded, unproductive capital for it.” People have not realized what has actually happened to the thinking of humanity. Just read most of these century reflections that appeared at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. If one did it differently, as I did in my book, which was later called “The Riddles of Philosophy”, then of course it was considered unhistorical. And one of these noble philosophers reproached me because the book was then called “World and Life Views in the 19th Century” for saying nothing about Bismarck in it. Yes, a philosopher reproached this book for that. Many other similar accusations have been made against this book because it tried to extract from the past that which has an effect on the future. But what did these critics usually do? They reflected. They reflected on what culture is, on what already exists. These thinkers no longer had any idea that earlier centuries had created culture. But now Albert Schweitzer comes along and I would like to say that he seems to have resigned himself to the future of philosophy. He says: It is actually not the fault of philosophy that it no longer plays an actual productive role in thinking. It was more the fate of philosophy. For the world in general has forgotten how to think, and philosophy has forgotten it along with the rest. In a certain respect, Schweitzer is even very indulgent, because one could also think: If the whole world has forgotten how to think, then at least the philosophers could have maintained it. But Schweitzer finds it quite natural that the philosophers have simply forgotten how to think along with all the other people. He says: “That thinking did not manage to create a world view of an optimistic-ethical character and to base the ideals that make up culture in such a world view was not the fault of philosophy, but a fact that arose in the development of thought.” - So that was the case with all people. —- “But philosophy was guilty of our world because it did not admit the fact and remained in the illusion that it really maintained a progress of culture.” So, with the other people, the philosophers have, as Albert Schweitzer says with his razor-sharp criticism, forgotten how to think; but that is not really their fault, that is just a fact, they have just forgotten how to think with the other people. But their real fault is that they haven't even noticed that. They should have noticed it at least and should have talked about it. That is the only thing Schweitzer accuses the philosophers of. “According to its ultimate destiny, philosophy is the leader and guardian of general reason. It would have been its duty to admit to our world that the ethical ideals of reason no longer found support in a total world view, as they used to, but were left to their own devices for the time being and had to assert themselves in the world through their inner strength alone.” And then he concludes this first chapter by saying: “So little philosophy was made about culture that it did not even notice how it itself, and the times with it, became more and more cultureless. In the hour of danger, the guard who was supposed to keep us awake slept. So it happened that we did not struggle for our culture.” Now, however, I ask you not to do this with these sentences of Albert Schweitzer, for example, by saying to yourself or a part of you: Well, that is just a criticism of German culture, and it does not apply to England, to America, and least of all to France, of course! Albert Schweitzer has written a great number of works. Among these are the following, written in English: “The Mystery of the Kingdom of God”; then another work: “The Question of the Historical Jesus”; then a third; and he has written some others in French. So the man is international and certainly does not just speak of German culture, but of the culture of the present day. Therefore it would not be very nice if this view were to be treated the way we experienced something in Berlin once. We had an anthroposophical meeting and there was a member who had a dog. I always had to explain that people have repeated lives on earth, reincarnation, but not animals, because it is the generic souls, the group souls, that are in the same stage, not the individual animal. But this personality loved her dog so much that she thought, even though she admitted that other animals, even other dogs, do not have repeated lives, her dog does have repeated lives, she knows that for sure. There was a little discussion about this matter – discussions are sometimes stimulating, as you know, and one could now think that this personality could never be convinced and that the others were convinced. This also became clear immediately when we were sitting in a coffee house. This other member said that it was actually terribly foolish of this personality to think that her dog had repeated earthly lives; she had realized this immediately, it was quite clear from anthroposophy that this was an impossibility. Yes, if it were my parrot! That's what it applies to! — I would not want that this thought form would be transferred by the different nationalities in such a way that they say: Yes, for the people for whom Albert Schweitzer speaks, it is true that culture is in decline, that philosophers have not realized it themselves, but — our parrot has repeated lives on earth! In the second chapter, Albert Schweitzer talks about “circumstances that inhibit culture in our economic and intellectual life,” and here, too, he is extremely sharp. Of course, there are also trivialities, I would say, of what is quite obvious. But then Albert Schweitzer sees through a shortcoming of modern man, this cultureless modern man, by finding that modern man, because he has lost his culture, has become unfree, and is unsettled. Well, I have read sentences to you by Max Rubner – they do not, however, indicate a strong collection of thoughts. The representative modern man is unsettled. Then Albert Schweitzer adds a cute epithet to this modern man. He is, in addition to being unfree and uncollected, also “incomplete”. Now imagine that these modern people all believe that they are walking around the world as complete specimens of humanity. But Albert Schweitzer believes that today, due to modern education, everyone is put into a very one-sided professional life, developing only one side of their abilities while allowing the others to wither away, and thus becoming an incomplete human being in reality. And in connection with this lack of freedom, incompleteness and lack of focus in modern man, Albert Schweitzer asserts that modern man is becoming somewhat inhumane: “In fact, thoughts of complete inhumanity have been moving among us with the ugly clarity of words and the authority of logical principles for two generations. A mentality has emerged in society that alienates individuals from humanity. The courtesy of natural feeling is fading.” - I recall the Annual General Meeting we had here, where courtesy was discussed! — ”In its place comes behavior of absolute indifference, with more or less formality. The aloofness and apathy emphasized in every way possible towards strangers is no longer felt as inner coarseness at all, but is considered to be a sign of sophistication. Our society has also ceased to recognize all people as having human value and dignity. Parts of humanity have become human material and human things for us. If for decades it has been possible to talk about war and conquest among us with increasing carelessness, as if it were a matter of operating on a chessboard, this was only possible because an overall attitude had been created in which the fate of the individual was no longer imagined, but only present as figures and objects. When war came, the inhumanity that was in us had free rein. And what fine and coarse rudeness has appeared in our colonial literature and in our parliaments over the past decades as a rational truth about people of color, and passed into public opinion! Twenty years ago, in one of the parliaments of continental Europe, it was even accepted that, with regard to deported blacks who had been left to die of hunger and disease, it was said from the rostrum that they had “died as if they were animals. Now Albert Schweitzer also discusses the role of over-organization in our cultural decline. He believes that public conditions also have a culture-inhibiting effect due to the fact that over-organization is occurring everywhere. After all, organizing decrees, ordinances, laws are being created everywhere today. You are in an organization for everything. People experience this thoughtlessly. They also act thoughtlessly. They are always organized in something, so Albert Schweitzer finds that this “over-organization” has also had a culture-inhibiting effect. “The terrible truth that with the progress of history and economic development, culture does not become easier, but more difficult, was not addressed.” — “The bankruptcy of the cultural state, which is becoming more apparent from decade to decade, is destroying modern man. The demoralization of the individual by the whole is in full swing. A person who is unfree, uncollected, incomplete, and lost in a lack of humanity, who has surrendered his intellectual independence and moral judgment to organized society, and who experiences inhibitions of cultural awareness in every respect: this is how modern man trod his dark path in dark times. Philosophy had no understanding for the danger in which he found himself. So she made no attempt to help him. Not even to reflect on what was happening to him did she stop him." In the third chapter, Albert Schweitzer then talks about how a real culture would have to have an ethical character. Earlier worldviews gave birth to ethical values; since the mid-19th century, people have continued to live with the old ethical values without somehow anchoring them in a total worldview, and they didn't even notice: “They in the situation created by the ethical cultural movement, without realizing that it had now become untenable, and without looking ahead to what was preparing between and within nations. So our time, thoughtless as it was, came to the conclusion that culture consists primarily of scientific, technical and artistic achievements and can do without ethics or with a minimum of ethics. This externalized conception of culture gained authority in public opinion in that it was universally held even by persons whose social position and scientific education seemed to indicate that they were competent in matters of intellectual life.” — ”Our sense of reality, then, consists in our allowing the next most obvious fact to arise from one fact through passions and short-sighted considerations of utility, and so on and on. Since we lack the purposeful intention of a whole to be realized, our activity falls under the concept of natural events. And Albert Schweitzer also sees with full clarity that because people no longer had anything creative, they turned to nationalism. "It was characteristic of the morbid nature of the realpolitik of nationalism that it sought in every way to adorn itself with the trappings of the ideal. The struggle for power became the struggle for law and culture. The selfish communities of interests that nations entered into with each other against others presented themselves as friendships and affinities. As such, they were backdated to the past, even when history knew more of hereditary enmity than of inner kinship. Ultimately, it was not enough for nationalism to set aside any intention of realizing a cultural humanity in its politics. It even destroyed the very notion of culture by proclaiming national culture. You see, Albert Schweitzer sees quite clearly in the most diverse areas of life, it must be said. And he finds words to express this negative aspect of our time. So, I would say, it is also quite clear to him what our time has become through the great influence of science. But since he also realizes that our time is incapable of thinking – I have shown you this with the example of Max Rubner – Albert Schweitzer also knows that science has become thoughtless and therefore cannot have the vocation to lead humanity in culture in our time. "Today, thinking has nothing more to do with science because science has become independent and indifferent to it. The most advanced knowledge now goes hand in hand with the most thoughtless world view. It claims to deal only with individual findings, since only these preserve objective science. It is not its business to summarize knowledge and assert its consequences for world view. In the past, every scientific person was, as Albert Schweitzer says, at the same time a thinker who meant something in the general intellectual life of his generation. Our time has arrived at the ability to distinguish between science and thinking. That is why we still have freedom of science, but almost no thinking science anymore. You see, Schweitzer sees the negative side extremely clearly, and he also knows how to say what is important: that it is important to bring the spirit back into culture. He knows that culture has become spiritless. But this morning in my lecture on education I explained how only the words remain of what people knew about the soul in earlier times. People talk about the soul in words, but they no longer associate anything real with those words. And so it is with the spirit. That is why there is no awareness of the spirit today. One has only the word. And then, when someone has so astutely characterized the negative of modern culture, then at most he can still come to it, according to certain traditional feelings that one has when one speaks of spirit today – but because no one knows anything about spirit – then at most one can come to say: the spirit is necessary. But if you are supposed to say how the spirit is to enter into culture, then it becomes so - forgive me: when I was a very young boy, I lived near a village, and chickens were stolen from a person who was one of the village's most important residents. Now it came to a lawsuit. It came to a court hearing. The judge wanted to gauge how severe the punishment should be, and to do that it was necessary to get an idea of what kind of chickens they were. So he asked the village dignitary to describe the chickens. “Tell us something more about what kind of chickens they were. Describe them to us a little!” Yes, Mr. Judge, they were beautiful chickens. — You can't do anything with that if you can't tell us anything more precise! You had these chickens, describe these chickens to us a little. — Yes, Mr. Judge, they were just beautiful chickens! - And so this personality continued. Nothing more could be brought out of her than: They were beautiful chickens. And you see, in the next chapter Albert Schweitzer also comes to the point of saying how he thinks a total world view should be: “But what kind of thinking world view must there be for cultural ideas and cultural attitudes to be grounded in it?” He says, “Optimistic and ethical.” They were just beautiful chickens! It must be optimistic and ethical. Yes, but how should it be? Just imagine that an architect is building a house for someone and wants to find out what the house should be like. The person in question simply replies: “The house should be solid, weatherproof, beautiful, and it should be pleasant to live in.” Now you can make the plan and know how he wants it! But that is exactly what happens when someone tells you that a worldview should be optimistic and ethical. If you want to build a house, you have to design the plan; it has to be a concretely designed plan. But the ever-so-shrewd Albert Schweitzer has nothing to say except: “There were just beautiful chickens.” Or: “The house should be beautiful, that is, it should be optimistic and ethical. He even goes a little further, but it doesn't come out much differently than the beautiful chickens. He says, for example, that because thinking has gone so much out of fashion, because thinking is no longer possible at all and the philosophers themselves do not notice that it is no longer there, but still believe that they can think, so many people have come to mysticism who want to work free of thought, who want to arrive at a world view without thinking. Now he says: Yes, but why should one not enter mysticism with thinking? So the worldview that is to come must enter mysticism with thinking. Yes, but what will it be like then? The house should be solid, weatherproof, beautiful and so that one can live comfortably inside. The worldview should be such that it enters mysticism through thinking. That is exactly the same. A real content is not even hinted at anywhere. It does not exist. So how does anthroposophy differ from such cultural criticism? It can certainly agree with the negative aspects, but it is not satisfied with describing the house in terms of what it should be: solid and weatherproof and beautiful and such that it is comfortable to live in. Instead, it draws up plans for the house, it really sketches out the image of a culture. Now, Albert Schweitzer does object to this to some extent, saying, “The great revision of the convictions and ideals in and for which we live cannot be achieved by talking other, better thoughts into the people of our time than those they already have. It can only be achieved by the many reflecting on the meaning of life...” So that's not possible, talking better thoughts into the people of our time than those they already have, that's not possible! Yes, what should one do then in the sense of Albert Schweitzer? He admonishes people to go within themselves, to get out of themselves what they have out of themselves, so that one does not need to talk into them thoughts that are somehow different from those they already have. Yes, but by searching within themselves for what they already have, people have brought about the situation that we are now in: “We are in the throes of the decline of civilization.” “We lost our way culturally because there was no thinking about culture among us,” and so on. Yes, all this has come about - and this is what Schweitzer hits so hard and with such intense thinking - because people have neglected any real, concrete planning of culture. And now he says: It is not enough for people to absorb something; they have to go within themselves. You see, you can say that not only Max Rubner, who cannot cope with his thinking everywhere, but even a thinker as sharp as Albert Schweitzer is not able to make the transition from a negative critique of culture to an acknowledgment of what must enter this culture as a new spiritual life. Anthroposophy has been around for just as long as Albert Schweitzer, who admittedly wrote this book from 1900 onwards. But he failed to notice that Anthroposophy positively seeks to achieve what he merely criticizes in negative terms: to bring spirit into culture. In this regard, he even gets very facetious. Because towards the end of the last part of his writing he says: “In itself, reflecting on the meaning of life has a significance. If such reflection arises again among us” – it is the conditional sentence, only worsened, because it should actually read: If such reflection arose again among us! - “then the ideals of vanity and passion, which now proliferate like evil weeds in the convictions of the masses, will wither away without hope. How much would be gained for today's conditions if we all just spent three minutes each evening looking up thoughtfully at the infinite worlds of the starry sky...” he comes to the conclusion that it would be good for people if they looked up at the starry sky for three minutes every evening! If you tell them so, they will certainly not do it; but read how these things should be done in my book “How to Know Higher Worlds”. One does not understand why the step from the negative to the positive cannot be taken here, one does not understand it! “and when attending a funeral, we would devote ourselves to the riddle of life and death, instead of walking thoughtlessly behind the coffin in conversation.” You see, when you are so negative, you conclude such a reflection on culture in such a way that you say: “Previous thinking thought to understand the meaning of life from the meaning of the world. It may be that we have to resign ourselves to leaving the meaning of the world open to question and to give our lives a meaning from the will to live, as it is in us. Even if the paths by which we have to strive towards the goal still lie in darkness, the direction in which we have to go is clear. As clear as it was that his chickens were beautiful chickens, and as clear as it is that someone says about the plan of his house: The house should be solid, weatherproof, and beautiful. Most people in the present see it as clear when they characterize something in this way, and do not even notice how unclear it is. "We have to think about the meaning of life together, to struggle together to arrive at a world- and life-affirming worldview in which our drive, which we experience as necessary and valuable, finds justification, orientation, clarification, deepening, moralization and strengthening... ” - The house should be beautiful and solid and weatherproof and in such a way that one can live well in it. In regard to a house one says so, in regard to a Weltanschhauung one says: The Weltanschhauung should be such that it can work justification, orientation, clarification, deepening, moralization and strengthening! - “and thereupon become capable of setting up and realizing definite cultural ideals inspired by the spirit of true humanity.” Now we have it. The sharpest, fully recognizable thinking about the negative, absolute powerlessness to see anything positive. Those people who deserve the most praise today – and Albert Schweitzer is one of them – are in such a position. Anthroposophists in particular should develop a keen awareness of this, so that they know what to expect when one of those who are “philosophers” in the sense of this astute Albert Schweitzer comes along, for example a neo-Kantian, as these people call themselves, and who now do not even realize that they have not only overslept thinking, but that they have not even noticed how they have overslept thinking. Of course, one cannot expect them to understand anthroposophy. But one should still keep a watchful eye on the way in which such people, who are rightly described by Schweitzer as the sleepy philosophers of the 19th and 20th centuries, now speak of anthroposophy. We should look into the present with an alert eye on all sides. A newspaper article begins by saying how ineffective Bergson seems in comparison to Kant. But then it goes on to say: Steiner's wild speculations and great spiritual tirades stand even less up to an epistemological test based on Kant. Steiner also believes that he can go beyond Kant and the neo-Kantians to higher insights. In fact, he falls far short of them and, as can easily be proven from his writings, has misunderstood them completely at crucial points. This is of course trumpeted out without any justification whatsoever in the world's newspapers. And then these people, who can think in this way, or who are far from being able to think the way Rubner can, say: You only have to ask contemporary science and you know very well what these supposed insights - these brain bubbles, as he calls them - actually mean. We have to pay attention to these things, and we must not oversleep them. Because this - as Albert Schweitzer calls it - thoughtless science can assert itself, it can assert itself in the world, and for the time being it has power. Today many people say that one should not look at power but at the law; but unfortunately they then call the power they have the law. Well, I will spare you the rest of the gibberish he presents, because it now goes into spiritual phenomena, which must also be examined by science today, and so on. But if the poor students do get hold of anthroposophy and absorb the “brain bubbles”, then Max Rubner gives them this advice: “But there is always something refreshing about working in a new, previously untilled field of the brain.” Some fields have been plowed over and over again! Now, when the poor students in anthroposophy get “brain bubbles” and then plow these brains, the bubbles in front of the plowshare will certainly disappear. So in this respect, the story is true again. To understand that which wants to enter our culture, which, according to the best minds, is admittedly disintegrating, indeed has already disintegrated, that is not really given to the best minds of the present either, insofar as they are involved in the present cultural industry. So it remains the case that when they are supposed to say what the house should be like, they do not take the pencil or the model substance to design the house – which is what anthroposophy does – but then they say: The house should be beautiful and strong and weatherproof and so that one can live comfortably in it. With the house one says so. With a worldview, one says that it should be optimistic, it should be ethical, one should be able to orient oneself in it, and now how all the things have been called, but which mean nothing other than what I have told you. You can see that it is necessary – and you will recognize it from the matter itself that this is necessary – to sometimes go a little beyond what is happening in civilization. That is why I have presented today's episodic reflection. Next Friday we want to talk further about these things, not say any more that the house should be beautiful and firm and weatherproof and so that one can live comfortably in it, the world view should be optimistic and ethical and so that one can orient oneself in it, and so on, but we really want to point to the real anthroposophy, to the spiritual life that our culture needs. |

| 165. The Conceptual World and Its Relationship to Reality: Lecture One

15 Jan 1916, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The central dogma of the Trinity, of the three divine persons, thus depended on realism or nominalism, on one or the other conception of the essence of universals. You will therefore understand that when Kant's philosophy increasingly became the philosophy of Protestant circles in Europe, a reaction took hold in Catholic circles. |

| The whole way of thinking, the whole way of looking at the world, is different in the progressive current of philosophy, which follows Kant, Fichte, Hegel, or earlier Cartesius, Malebranche, Hume, up to Mill and Spencer. It is a completely different kind of intellectual research, a completely different way of thinking about the world, than that which emerged, for example, in Gratry and the numerous neoscholastics who wrote everywhere, in France, Spain, Italy, Belgium, England, and Germany; for there is a wealth of neoscholastic literature in all countries. |

| 165. The Conceptual World and Its Relationship to Reality: Lecture One

15 Jan 1916, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

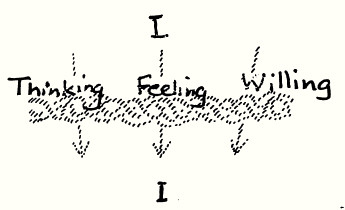

Tomorrow I would like to briefly return to the spiritual side of the early days of Christianity and its lasting impact. This will lead to some deeper insights into the public lectures of the last few days. Today I would like to give a kind of philosophical introduction to this, to familiarize you with some history, because it is good if we, within the spiritual science movement, also know something of how people strive in the rest of the world to get to the bottom of the world's mysteries, how they think and feel about these mysteries in the world. If you look at the history of philosophy from the beginning to the present day, you will basically only find certain philosophical currents discussed, philosophical currents that are close to most contemporary philosophers. However, one would be quite wrong to see everything that exists in the present in terms of such more philosophical research paths in what is usually found. For example, most of you are unaware that during the 19th century, particularly in the second half of the 19th century and especially towards the end of the 19th century, there was a lively philosophical life within the Catholic Church that continues to this day. that within the Catholic Church, a very peculiar philosophical direction, differing from the other philosophy of the world, was cultivated by the learned priesthood and is cultivated by many, so that in this field one has a rich literature, at least as rich a literature as on other directions of philosophical activity. And this literature is called the literature of Neuscholastik. A curious circumstance has led to the fact that the school, which flourished in the middle of the Middle Ages, which basically began with Scotus Erigena and then continued through Thomas Aquinas to the times of Duns Scotus, reappeared in the 19th century, and indeed out of a very specific need for knowledge, albeit one colored by religious belief. Particularly from the second third of the 19th century onwards, we see this direction of neo-scholasticism emerging in Catholic circles. In all Central and Western European languages, books upon books are being written in an attempt to understand anew what was lived in scholasticism. And if one tries to explore the inner reason why scholasticism is reviving, one must actually open up a broad view. And this is what we want to point out today. In the lectures I have given in the last few days, I have repeatedly emphasized that one way to spiritual-scientific knowledge is through a very special treatment of thinking, of concepts, of logic; that through the influence of the exercises that lead to this development of thinking, the human being no longer thinks in his physical body, but in his ether body. Thus he not only thinks dead conceptual logic, but he lives in the activity of thinking, that is, he lives and moves in his ether body, as we can express it technically. It is a living into the etheric body when logic itself comes to life, when — as I have put it in popular terms — the statue, through which one can visualize the logic at work in ordinary life, comes to life, when the human being becomes alive in his ether body, that is, the concepts are no longer dead concepts, but those living concepts begin, of which I have said for years that the concept gains life, as if one were with one's soul in a living being. For many centuries, humanity has basically known nothing of this liveliness as the truth of concepts and ideas in external philosophy. I have tried to point out this fact in the first chapter of my “Riddles of Philosophy” that was added to the new edition. Even in the last philosophical periods of Greek civilization, humanity actually no longer knew anything philosophically about the possible liveliness of concepts and ideas. Let us keep that in mind. Initially, the Greeks — you can read about this in my “Riddles of Philosophy” — had concepts and ideas in the same way that people today have sensory perceptions, a color, a sound or a smell. The great Plato, up to Aristotle, and even more so the older philosophers, did not believe that they had formed the concept, the thought, internally, but that they received it from things, just as one receives red or blue, that is, the sensory perceptions. Then came the time - and I have described how this continues in cycles - when one no longer felt inwardly that the things had given one the concept, but one only felt that the concept arose in the soul. And now one did not know what to do with the concept, with the inner idea, which the Greek had still believed he received from things. Hence arose those scholastic problems, those scholastic puzzles: What does the concept mean at all in relation to things? — The Greek could not ask it that way, because he had the consciousness that things give him the concepts, so the concepts belong to things as colors belong to things. — That ceased when the Middle Ages came. Then one had to ask: What kind of relationship does something that arises in our mind have to things? And besides: the things out there are many and varied and individual, but the concepts are general, a unity. We go through the world and encounter many horses; we form the unified concept of horse out of these many horses. Every horse coincides with the concept of horse. Today, many people, who are even less familiar with the concept than the medieval philosophers, who saw it as a sharp problem, say: Well, the concept is just not in the things themselves. I have repeatedly mentioned a comparison that my friend, the late Vincenz Knauer, a great connoisseur of medieval philosophy, often used for those people who say: Out there is only the material of the animal, the soul makes the concept. Old Knauer would always say: People claim: The lamb is outside, but what is really there is only matter. The wolf is outside, but what is really there is only matter. The soul creates the concept of the lamb, and the soul creates the concept of the wolf. And old Knauer said: If only matter were really present, and you locked up a wolf that ate nothing but lambs, then when it had discarded its old matter it would finally be only lamb, because it would have only lamb matter in itself. But one would notice with amazement that it would still have remained the wolf, that something else must therefore be present in addition to matter. For medieval scholasticism, this presented a significant problem, a significant enigma. The scholastics said to themselves: the concepts are the universals because they encompass many individual things. And they could not say, as today's man likes to say, that these universals are only something that has arisen in the mind of man, that has nothing to do with things. These medieval philosophers distinguished three types of universals. First, they said, universals are ante rem, before the thing, before what you see out there, so the universal “horse” is thought of before all possible sensual horses, as a thought in the deity. So said medieval scholasticism. Then there are universals in re, in things, and specifically as essence in things, precisely what matters. The universal “wolf” is what matters, and the universal “lamb” is what matters. They are what ensures that the wolf does not become a lamb, even if it eats nothing but lambs. And then there is a third form in which the universals exist, that is: post rem, after the things as they are in our minds, when we have considered the world and subtracted them from the things. The medieval scholastics attached great importance to this distinction, and it was this distinction that protected them from that skepticism, from that dissection, which cannot get to the essence of things, for the reason that they consider the concepts and ideas that man in his soul gains from things to be only a product of the soul and do not imagine anything about them that could have any significance for things themselves. The particular form of this skepticism can be found in one form with Hume and in another form with Cart. There, concepts and ideas are only that which the human mind forms as ideas. Through concepts and ideas, man can no longer approach things. For theologians who want to be philosophers at the same time, who thus want to penetrate theology philosophically, a very special difficulty has arisen and will always arise. For the theologian is dependent not only on seeing the things in the world, but also on thinking them in a certain relationship to the divine essence, and he gets into difficulties when he and which form the content of the only ideal knowledge – if one does not ascend to spiritual science – cannot himself bring these into any relationship with the Godhead, that is, think as universals ante rem, as universal concepts before the things. Now there is something very significant connected with what I have said. There will always be people who cannot see anything in the concept that has to do with things, who only see the material in things outside, and on the other hand, there are those who can see something real in the concepts that has to do with the things themselves, that is, what is in the things and what the human mind draws out of the things, what the human mind makes out of universals in re into universals post rem. Those who recognize that the concepts have a reality outside the human mind were called realists in the Middle Ages and later, especially in Catholic philosophy. And the view that the concepts and ideas have a real significance in the world is called realism. The other view, which assumes that concepts and ideas are fabricated only in the human mind, as it were, as words, is called nominalism, and its representatives are called nominalists. You will easily see that the nominalists can actually see the real only in the manifold, in the multitude. Only the realists can see something real in the comprehensive, in the universal. And here we come to the point where a particular difficulty arose for the philosophizing theologians. These Catholic theologians had to defend the dogma of the Trinity, of Father, Son and Holy Ghost, the three persons in the Godhead. After the development of ecclesiastical theology, they could not help saying: the three persons are individual, complete entities, but at the same time they are supposed to be one unity! If they had been nominalists, the divinity would always have fallen apart into three persons for them. Only the realists could still think of the three persons under one universal. But for that, the universal concept had to have a reality; for that, one had to be a realist. Therefore, the realists got along better with the Trinity than the nominalists, who had great difficulties and who, in the end, when scholasticism was already coming to an end and had degenerated into skepticism, could only hide behind the fact that they said: You cannot understand how the three persons are to be one divinity; but that is precisely why you have to believe it, you have to give up understanding; something like that can only be revealed. The human mind can only lead to nominalism, it cannot lead to any kind of realism. And basically it is the Hume-Kantian doctrine that has become pure nominalism by way of phenomenalism. The central dogma of the Trinity, of the three divine persons, thus depended on realism or nominalism, on one or the other conception of the essence of universals. You will therefore understand that when Kant's philosophy increasingly became the philosophy of Protestant circles in Europe, a reaction took hold in Catholic circles. And this reaction consisted in saying to oneself on this ground that one must now again take a close look at the old scholasticism, one must fathom what scholasticism actually meant. In short, because they could not arrive at a new way of understanding the spiritual world, they tried to reconstruct scholasticism. And a rich literature arose that set itself the sole task of making scholasticism accessible to people again. Of course, this literature was only read by Catholic theologians, but on a large scale. And for those who are interested in everything that is going on in the intellectual culture of humanity, it is by no means useless to take a brief look at the extensive literature that has come to light. It is useful to take a look at this neoscholastic literature if only because it allows us to see how black and white can coexist in the world – please note that the word has no negative connotation here! The whole way of thinking, the whole way of looking at the world, is different in the progressive current of philosophy, which follows Kant, Fichte, Hegel, or earlier Cartesius, Malebranche, Hume, up to Mill and Spencer. It is a completely different kind of intellectual research, a completely different way of thinking about the world, than that which emerged, for example, in Gratry and the numerous neoscholastics who wrote everywhere, in France, Spain, Italy, Belgium, England, and Germany; for there is a wealth of neoscholastic literature in all countries. And all the orders of the Catholic priesthood have taken part in the discussions. The study of scholasticism became particularly lively from 1879 onwards, when Pope Leo XIII's encyclical “Aeterni patris” was published. In this encyclical, Catholic theologians were made to study Thomas Aquinas as a matter of duty. Since that time, a rich literature has emerged in the tradition of Thomism, and the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas has been thoroughly studied and interpreted. However, the whole movement had already begun earlier, so that today libraries can be filled with the many brilliant works that have emerged from this renewal of Thomism. You can educate yourself, for example, from a book like “The Origin of Human Reason” or from many French books or, if you prefer, from numerous works by Italian Jesuits and Dominicans, with which this philosophy has been driven again. Much ingenuity has been applied to the study of scholasticism in all countries – an ingenuity that people, even those who study philosophy today, usually have no idea of, because they do not have the necessary interest to pay attention to all sides of human endeavor. The need to take a stand against Kantianism arose from this side, which, by becoming pure nominalism, especially in the second half of the 19th century, removed the ground from under Catholic theology. I am now speaking purely historically, not to evaluate anything, not even to refute anything, or to agree with anything, but purely historically. And then one can see that basically, to this day, people are still endeavoring to understand what the concept and the thinking are actually about. In the modern age, people can no longer achieve anything with the concept in its old sense. It must be revitalized if we are to make progress. Long-term attempts must be made to understand, theoretically, with the mere concept of the image, what significance thinking has for divinity. Others have endeavored in other ways. For example, a very significant current has emerged that is even very close to Catholicism and has been pursued by priests within Catholicism, but it has not found the favor of Catholic authority to the extent that scholasticism did. In the encyclical “Aeterni patris”, Catholic theologians were even dutifully encouraged to renew the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, to resurrect it. Another direction has not received as much favor from the Catholic authorities: that is the direction of Rosmini-Serbati and Gioberti. Rosmini, who was born in Rovereto near Trento and died in nearby Stresa in 1855, expressed his aspirations particularly in works that were not actually published until after his death. And it is interesting to see how Rosmini wanted to work his way up by examining the real value of the concept. Rosmini came to understand that man has the concept present in his inner experience. A person who is only a nominalist stops at the fact that he experiences the concept internally and passes over the question of where the concept is present in reality. Rosmini, however, was ingenious enough to know that even if something reveals itself within the soul, this does not mean that it has reality only within the soul. And so he knew, in particular, by starting from the concept of being, that the soul, by experiencing the concepts, at the same time experiences the inner essence of things as they live in the concepts. And so Rosmini's philosophy consisted in seeking inner experiences, which for him were experiences of concepts, but in doing so he did not arrive at the liveliness of the concepts, only at the diversity of the concepts. And now he sought to specify how the concept lives simultaneously in the soul and in things. This is very clearly expressed in the work by Rosmini that was left behind and is entitled “Teosofia”. Within Catholicism, others also held a similar point of view, but Rosmini is one of the most ingenious. Now, however, Catholic theology finds such a direction as Rosminian somewhat inconvenient and uncomfortable, because it is very difficult for this side to reconcile the concept of revelation with this theory of concepts. For the concept of revelation amounts to the fact that the highest truths must be revealed. They cannot be experienced inwardly in the soul, but must be revealed outwardly in the course of human history. Man can only approach reality with his concepts to a certain degree, and the sphere of revelations rises above this sphere of concepts. From this point of view, the scholastics had to stand. This is also compatible with what Catholicism still regards as its core today, better than the Rosminian experienced concepts. Because when you have experienced concepts, it is actually God who lives in you. And basically, Catholic theology is horrified when people claim that God lives in man. That is why Leo XIII declared Rosmini's philosophy heretical in the 1880s by a decree of his own and forbade Catholic theologians to study and teach Rosmini's philosophy unless they had permission from their superiors. For in this way, strict measures are taken within the operations of Catholic theologians. I do not know whether this is always the case without exception. In the publications of Catholic theologians of all camps, one will in any case always find the seal of the superior episcopal authority. This then means that Catholic theologians are allowed to study such a work. There are certain exceptions for those who are university teachers, but things are handled very strictly, at least in theory. In this way, one also sees the attempt to work one's way into an understanding of the relationship between thinking and the world. I would like to make an interjection here that is of a completely different nature. Such interjections are sometimes necessary. Many of our friends believe that they are doing our movement a great favor when they explain to Catholic theologians, for example, that we are not at all anti-Christian and that we are in fact seeking an honest concept of Christ. And in their good faith, our friends go so far as to tell this or that Catholic theologian about the way we characterize Christianity. For our friends then believe, in their – forgive me – naivety, that they can make these theologians see that we are good Christians. But they can never admit that as Catholic theologians! My dear friends, we will be much more agreeable to them if we do not seek the Christ, if we do not care about the Christ! For it is not a matter for them – this must always be borne in mind – that someone is seeking this or that concept of Christ, but for them it is a matter of the supremacy of the Church. And precisely if one had an equally good or better concept of Christ outside the Church, then one would be fought against most of all. Thus, those of our friends who are most gullible do us the greatest harm, who go to Catholic theologians and try to convince them that we are not anti-Christian. For they will say: It is even worse if a concept of Christ could take root outside the church. One must judge the things of life according to one's circumstances and not according to one's naive opinion. We will be fought against particularly sharply if the theologians should make the discovery that we understand something of the inner existence of Christianity that could make a convincing impression on a larger circle of humanity. But it can be seen that it had become necessary to work one's way into an understanding of the concept and its relationship to reality. And here it must be said: what is contained in the writings of Rosminis is among the most brilliant things that have been accomplished in this direction in modern times. He has worked through this for all areas, and it could be of very special value if one studied Rosmini's concepts of beauty, his aesthetic concepts. Rosmini's theory of beauty, his aesthetics, is something particularly valuable that one should engage with in order to see how a modern mind works its way up to standing at the gateway to spiritual science and just not being able to enter into spiritual science. This can be studied to such an outstanding degree in Rosmini. Thus we find that there are really spiritual currents that want to work towards an understanding of the concept, but do not come to realize that we are now living in a time when the concept must become alive if one wants to enter into reality. So the concept has gone through a certain history. I have dealt with this history in part in my book “The Riddles of Philosophy” in that first chapter of which I spoke. But here I would like to point out something further. We can say, then, that the concept continues to develop. There was a time when the concept was a perceived concept, as color or sound was perceived. This was the case with the Greeks. Plato is just the last one to speak so realistically about the concepts that one can see how something of the understanding for such a grasp of the concepts resonates in him. With Aristotle it is already different. Then comes the Middle Ages, where one has the concept purely rationally, and where one seeks how it relates to things as a universal, and where one reaches for bridges and comes to the structure: ante rem, in re, post rem – before, in, after things. Then comes the time when the concept is fully understood in a nominalistic way. This extends into our time. But the reaction is asserting itself, the side currents that seek the concept as an inner experience, as with Rosmini. From here (see diagram: Rosmini) one would come to the life or experience of the concept. So the concept would be chained, so to speak, to the physical body in this time (see diagram: before Plato to the Middle Ages), and now pass over to the etheric body. The concept would lead to the clairvoyant experience of the concept. But then one would have to say that the entire earlier perceived concept and the nominalistic and rational concept have developed out of an atavistic clairvoyance of the concept, and that now the way in which the concept is to be experienced is a conscious one, whereas in earlier times it was more subconscious. And indeed, if you go from Plato, from the Greek philosophers, who had the concept as a perceived one, to the echoes of Zarathustrianism, you have this atavistically grasped – or perhaps one does not need to say “atavistic” because this expression is only valid today – so dream-like, clairvoyantly experienced concept.

Thus the Near Eastern philosophies presented the concept as something that they experienced pictorially. Persian philosophy sees in the “horse in general” a being in general that is specified and differentiated from the individual horse, still something living. The Persians called this “Feruer”. This is abstracted and becomes the Platonic idea. The Persians' Feruer becomes the Platonic idea. Abstraction is gaining more and more ground because thinking is only experienced in the physical body. We must return to the consciously experienced concept. In this field you see a wonderful cycle taking place from the old clairvoyance of the concept through what the concept had to become in the age of physical experience: the merely rational concept, the merely conceptualized concept, the merely logical concept. I have often emphasized that logic only came into being through Aristotle, when one had the concept only as a concept. Before that, for the experienced concept, one did not need logic. And now logic comes to life, the statue of logic comes to life. This example of the concept shows once again what can be seen in general and on a large scale. We also have to work our way into the whole course of human development in the individual, because then we understand more and more clearly the meaning underlying the spiritual current to which we belong. And we really do become more and more objective through these things, but that is also necessary. Where would we end up if objectivity were not understood at all and our dear friends were to drag everything more and more into the personal sphere! Our task must be to work objectively, and the purely personal must recede more and more. | |||||||||||||||

| 221. Earthly Knowledge and Heavenly Insight: The I-Being can be Shifted into Pure Thinking I

03 Feb 1923, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Rosenkranz was a Hegelian, but his Hegelianism was, first of all, colored by a careful study of Kant – he saw Hegel, so to speak, through the glasses of Kantianism – but, in addition, his Hegelianism was strongly colored by his study of Protestant theology. |

| 221. Earthly Knowledge and Heavenly Insight: The I-Being can be Shifted into Pure Thinking I

03 Feb 1923, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|