The Origin and Development of Eurythmy

1918–1920

GA 277b

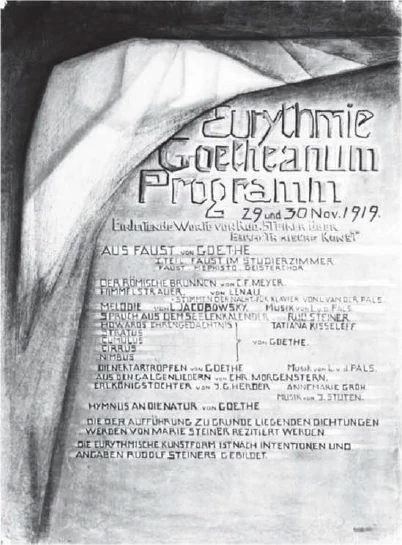

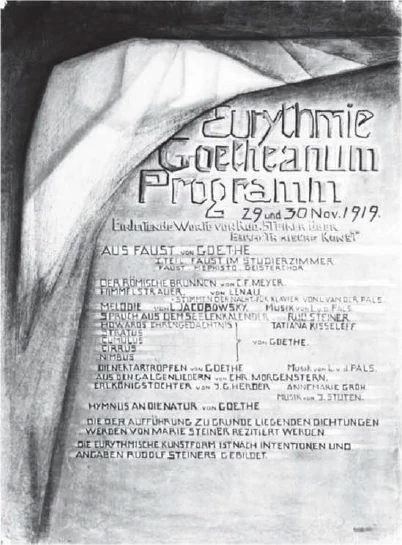

29 November 1919, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

35. Eurythmy Performance

Dear Ladies and Gentlemen.

Allow me to say a few words in advance of the rehearsal of our eurythmic art that we will present to you.

Human speech, through which we communicate in life and which is used by poetry to express artistic things, is, as is well known, a product of the human larynx and its neighboring organs. Everything that we pay attention to in ordinary life with regard to human speech is the audible. In contrast to ordinary audible speech, eurythmy is conceived as a silent but visible language. But eurythmy is not conceived as a silent but visible language in the same way that ordinary human gestures or pantomime are conceived as a silent language. Rather, what is attempted in eurythmy is derived from the human being himself in a completely lawful way, derived from the human being himself in such a way that it is based on Goethe's world view and artistic attitude.

Just as Goethe tried to gain a lifelike understanding of nature by examining living beings to see how the individual organ expresses the whole organism, and how the whole organism is only a more complicated structure that represents a transformation of the individual organ , then we try to listen to an activity of the person that is produced by an organ system – in this case the larynx and its neighboring organs – in order to then apply it to the possibilities of movement of the whole person.

By means of a certain kind of – to use this Goethean expression – sensual-supersensible seeing, we can see what we do not see in ordinary life when we listen to the person speaking. You only need to remember how it is clear even from physics that, as I speak here, my speaking sets the air in motion, in wave-like motion, so you already have a concept of that movement, which is a concomitant of what we ourselves hear. But one can go further back, precisely through a kind of sensory-supersensory seeing. If one has this ability of sensory-supersensory seeing, one can convince oneself of the movements, and namely the movement structures, that are present in the human larynx and its neighboring organs when a person speaks.

These movement possibilities can then be transferred to the whole person. Just as, in Goethe's sense, the whole plant is only a more complicated leaf, so the whole person can move his limbs in the way that the larynx, tongue, palate and so on move when a person speaks. Visible language is therefore what is attempted through eurythmy.

But this is how you come particularly close to an artistic element. Isn't it true, my dear audience, that the artistic is based on our ability to delve into the essence of things, without abstract concepts and ideas. All that is mere knowledge, all that is developed imagination, disturbs what is actually artistic. We must delve into the riddles of existence, and you can take on the mediation of presentation and concept. It is precisely this that happens unconsciously through the eurythmy on the part of the spectator. It happens quite consciously on the part of those who are performing this eurythmy.

For in our ordinary language, two sides are confused: one is the element of thought that permeates our words from the soul. This is something that is lost from the artistic side of language; it is also something that is more closely aligned with the conventional way in which we communicate in life, and which is how the philistine, everyday, inartistic element of language comes about.

But the other aspect of the soul also works in language: the will element. In ordinary language, the thought element works together with the will element. Now, esteemed attendees, we omit precisely this thought element by bringing the will impulses out of the human being in the silent language of eurythmy. And we express these impulses of will through the entire world of the human limbs. So you see, as it were, the human being himself becoming a mute speech organ on the stage before you. And what he expresses through these movements of form, and also through his movements in space, is the same as what is otherwise expressed through audible speech.

By immersing ourselves in the human being itself, in order to allow ourselves to be revealed what is predisposed in the innermost part of the human being as possibilities of movement, we switch off the very element of language, and thus penetrate deeper into the essence of the human being without concepts and ideas, in direct contemplation. And in this way we achieve something that is fundamentally artistic. You can see that here we are attempting something that avoids mere gesture, pantomime, mimicry, and arbitrary connections – as is often the case in dance – between the content of the soul and the external impression.

In this way, eurythmy is something like the art of music itself. Just as musical art does not achieve its full value when it is merely tone painting, so eurythmic movements do not achieve what we are seeking artistically if they merely express in pantomime what is going on in the soul. They do not do this; but just as in music the essential lies in the lawful succession of the tones, in the melodious element, so here the essential lies not in the direct expression, but in the lawful sequence of the movements. Eurythmy is therefore music that is visible on the outside. And so it is that there is nothing arbitrary about two people or two groups of people in different places eurythmizing or performing the same thing, because the individual possibilities for expression are not allowed to differ any more than when two pianists play the same piece of music according to their personal interpretation.

And all the feelings that otherwise animate our speech, such as passion and sorrow, joy and enthusiasm, and so on, we can also express through the forms and especially through groups – whereby the individual personalities interact through the different movements of these groups. So it is a mute language of people in motion through which eurythmy seeks to work.

Of course, everything aesthetic must have an immediate effect, and I am only saying these few words to you in advance so that you can see the artistic sources from which this eurythmy is drawn. Just as in music there is an inner lawfulness of tones in the sequence of tones, of melody and so on, here we come to the lawfulness of human movement itself.

You will hear the silent language of eurythmy performed before you accompanied, on the one hand, by music, which is essentially just another expression, an expression with different means. You will also hear the recitation on the other hand. What is heard in the recitation becomes visible on the stage through the movements of the people there. The two will run in parallel. A piece of poetry, for example, will be recited, and the art of poetry will be presented in eurythmy at the same time – one and the same.

However, it must be taken into account that the art of recitation, as it is practiced today, is not well suited for eurythmy. For today, in the art of recitation – and it is precisely in this that the greatness of the art of recitation is seen – the prose content of the poems is actually taken into account, not the rhythmic, the metrical, the rhyming that underlies them. But this must be taken into account precisely in the art of recitation that is intended to serve the rhythmic presentation. So we have to go back to the good old forms of recitation – and [in doing so] we want to develop a feeling for the artistic again, a better feeling than our current, somewhat inartistic times. In the artistic, our present humanity also often seeks the prose content of a poem, the literal content in a poem.

One need only recall how Schiller, for example, before he had the literal content of some of his poems in mind, had a melody in mind; and it was only for this melody, which now lived in his soul in a certain way, that he then sought the literal content. This is how the best of Schiller's poems came into being. The real poet needs the formal element that underlies the prose element of life.

Now we will first have to perform a scene from the first part of Goethe's “Faust” for you. There we will, of course, present what are, so to speak, everyday events, in a manner appropriate to the stage. However, anyone who has seen many of the attempts that the directorial art of modern theater has made to bring Goethe's “Faust” to the stage in a dignified manner knows how difficult it is to that Goethe has put into Faust, to really bring it out in the presentation, when Goethe, as is the case in so many places in Faust, allows the supersensible, the spiritual, to play into his poetry. In many places, as you know - also in the first part, but especially in the second part of Faust - the spiritual and the supersensible play a role. One can go through the various directorial skills that have been applied: a great deal was really achieved in the 1880s, even in the 1880s. I myself got to know Wilbrandt in the 1880s, with his amiable directorial skills, who tried to bring the whole of “Faust” to the stage. It was also a kind of deepening for the interpretation of the mystery play that Devrient brought to the stage and so on. Much has been tried; but something unsatisfactory always remains, especially in the scenes where the spiritual and supersensible play a role and should be presented.

So now, while we present the rest of the scenes in a purely theatrical way, we are trying to bring out the “ghost scene” through eurythmy. Before the break, we will present the first scene of the first part of “Faust” in a purely theatrical way, as far as this can be considered. So the scene in the study, the poodle scene, where the poodle disturbs Faust while he is translating the Bible; and then the ghosts enter, and through the silent language of eurythmy we try to bring out what is in this world poem with regard to the ghost scene.

Goethe was aware that he had put so much inwardly human into his “Faust” poetry that he had not actually thought of staging the first part of “Faust” until the 1820s. He was then aware that he had adapted “Faust II” for the stage; but it was not performed until after Goethe's death. But you see, Faust was such a huge piece of world literature that other people came up with the idea of staging Faust, of actually bringing it to the stage. Goethe hadn't thought of that; for him, Faust was simply something portrayed from within, from the human perspective.

My old friend and teacher, Karl Julius Schröer, was very friendly with Laroche, who was still a famous actor at the time of Goethe. Laroche came to Goethe at the head of a deputation with the proposal – it was only at the end of the 1790s – to bring Faust to the stage. Laroche reported to Schröer: “Yes, Goethe gave us a good telling off! He was furious when he heard that we wanted to stage Faust. He said to us, 'You fools!' You see, with Goethe, a good deal of anger was needed – and surprise. Goethe, who had really become a well-mannered gentleman by that time, the “fat privy councillor with the double chin”, was not easily so naughty to such excellent people as, for example, Laroche, when he called them “donkeys”. He must have really believed that it was not possible to stage “Faust”. He also spoke about it more often later on.

But attempts were repeatedly made to bring Faust to the stage, and rightly so. We now believe that for certain scenes, the mystery that Goethe has woven into his Faust can be brought out by means of eurythmy in certain places. Of course, you, esteemed attendees, should consider this as just an experiment; and I would ask you to consider what we are able to present to you today as just the beginning of the art of eurythmy, which will be perfected later.

So, before the intermission, we will present the first part of the first scene from the first part of Faust, and then after the intermission we will present poems, poetry, and music, where we will do everything entirely in eurythmy. In the presentation of the scene from Faust, only a few parts are in eurythmy. But in the second part of our program, we will then present everything to you in full eurythmy. And so I ask you to please take the whole performance as an exercise in forbearance; for we are actually only at the beginning with the eurythmic art that seeks to achieve what I have presented.

However, we believe that if our contemporaries show the right interest in this new art, it can be perfected, either by us or by others – probably the latter – and that the time will come will come when this art, which uses the whole person as an instrument, thus the highest thing we have in existence, will be able to establish itself as a fully-fledged art alongside other older fully-fledged arts.

Ansprache zur Eurythmie

Meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden!

Gestatten Sie, dass ich der Probe, die wir Ihnen vorführen werden aus unserer eurythmischen Kunst, einige Worte vorausschicke.

Die menschliche Sprache, durch die wir uns im Leben verständigen, und welche benutzt wird von der Dichtkunst, um Künstlerisches zum Ausdrucke zu bringen, sie ist, wie bekannt ist, ein Erzeugnis des menschlichen Kehlkopfes und seiner Nachbarorgane. Alles dasjenige, worauf wir unsere Aufmerksamkeit im gewöhnlichen Leben wenden gegenüber der menschlichen Sprache, das ist das Hörbare. - Im Gegensatze zu der gewöhnlichen hörbaren Sprache ist Eurythmie gedacht als eine stumme, aber sichtbare Sprache. Aber nicht so, wie schon die gewöhnliche menschliche Gebärde, wie die pantomimische Darstellung eine stumme Sprache ist, ist Eurythmie gedacht als eine stumme, aber sichtbare Sprache, sondern dasjenige, was hier als Eurythmie versucht wird, das ist in einer ganz gesetzmäRigen Weise herausgeholt aus dem Menschen selbst, so herausgeholt aus dem Menschen selbst, dass dabei zugrunde gelegt ist Goethes Weltanschauung und künstlerische Gesinnung.

So wie Goethe versucht hat, eine lebensvolle Lehre der Natur dadurch zu gewinnen, dass er bei Lebewesen untersucht hat, inwieferne das einzelne Organ zum Ausdruck bringt den ganzen Organismus, und wiederum der ganze Organismus nur ein komplizierteres Gebilde ist, das eine Umwandlung darstellt des einzelnen Organs, so versuchen wir auf eine Tätigkeit des Menschen, die hervorgebracht wird durch ein Organsystem - eben den Kehlkopf und seine Nachbarorgane -, so versuchen wir zu erlauschen, was da eigentlich vorgeht in dem Kehlkopf und seinen Nachbarorganen, um das dann anzuwenden auf die Bewegungsmöglichkeiten des ganzen Menschen.

Man kann durch eine gewisse Art - um uns dieses Goethe’schen Ausdrucks zu bedienen: sinnlich-übersinnlichen Schauens dasjenige nämlich sehen, was man im gewöhnlichen Leben nicht sicht, wenn man dem sprechenden Menschen zuhört. Sie brauchen ja nur sich zu erinnern, wie selbst durch die Physik klar wird, dass, indem ich hier spreche, durch mein Sprechen die Luft in Bewegung, in wellenartige Bewegung gebracht wird, so haben Sie schon einen Begriff von jener Bewegung, die Begleiterscheinung ist desjenigen, was wir selbst hören. Man kann aber weiter zurückgehen, eben durch eine Art sinnlich-übersinnliches Schauen, man kann sich, wenn man diese Fähigkeit des sinnlich-übersinnlichen Schauens hat, davon überzeugen, welche Bewegungen, und namentlich Bewegungsanlagen im menschlichen Kehlkopfe und seinen Nachbarorganen vorhanden sind, wenn der Mensch spricht.

Diese Bewegungsmöglichkeiten kann man dann übertragen auf den ganzen Menschen. So wie die ganze Pflanze im Sinne Goethes nur ein komplizierteres Blatt ist, so kann der ganze Mensch so seine Glieder bewegen, wie sonst Kehlkopf, Zunge, Gaumen und so weiter sich bewegen, wenn der Mensch spricht. Sichtbare Sprache also ist dasjenige, was versucht wird durch die Eurythmie.

Dadurch aber kommt man einem künstlerischen Element ganz besonders nahe. Nicht wahr, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, das Künstlerische beruht ja darauf, dass wir uns vertiefen können in das Wesen der Dinge, ohne abstrakte Begriffe und Ideen. Alles dasjenige, was bloße Erkenntnis ist, alles dasjenige, was ausgebildete Vorstellung ist, das stört das eigentlich Künstlerische. Wir müssen uns hineinvertiefen in die Rätsel des Daseins, und Sie können die Vermittlung von Vorstellung und Begriff aufnehmen. Gerade das geschieht unbewusst durch die Eurythmie von Seiten des Zuschauers. Das geschieht ganz bewusst von Seiten derjenigen, die eben diese Eurythmic ausführen.

Denn in unserer gewöhnlichen Sprache sind zwei Seiten durcheinanderwirkend: Das eine ist dasjenige, was als das Gedankenelement von der Seele aus unsere Worte durchdringt. Das ist etwas, was von dem Künstlerischen der Sprache wegfällt; das ist auch etwas, was sich mehr anlehnt an das Konventionelle, wodurch wir uns verständigen im Leben, wodurch also das philiströs-alltägliche, unkünstlerische Element der Sprache zustande kommt.

Aber in der Sprache wirkt auch die andere Seite des Seelischen: das Willenselement. In der gewöhnlichen Sprache wirkt zusammen das Gedankenelement mit dem Willenselement. Nun, sehr verehrte Anwesende, lassen wir gerade dieses Gedankenelement weg, indem wir die Willensimpulse aus dem Menschen herausholen in dieser stummen Sprache der Eurythmie. Und wir drücken diese Willensimpulse durch die gesamte Gliedmaßenwelt des Menschen aus. So sehen Sie gewissermaßen den Menschen selbst zu einem stummen Sprachwerkzeuge werden vor Ihnen auf der Bühne. Und was er ausdrückt durch diese Formbewegung, auch durch seine Bewegungen im Raume, das ist dasselbe, was sonst ausgedrückt wird durch die hörbare Sprache.

Indem wir uns so in das Menschenwesen selbst vertiefen, um uns offenbaren zu lassen, was im Innersten des Menschen als Bewegungsmöglichkeiten veranlagt ist, schalten wir gerade das Vorstellungselement der Sprache aus, dringen dadurch tiefer in das Wesen des Menschen ohne Begriffe und Ideen ein, in unmittelbarer Anschauung. Und wir erreichen gerade dadurch etwas elementar Künstlerisches. Sie sehen daraus, dass hier versucht wird etwas, bei dem alle bloße Geste, alles Pantomimische, alles Mimische, aller willkürliche Zusammenhang -wie es sonst in der Tanzkunst der Fall ist oftmals zwischen dem seelischen Inhalte und dem äußeren Eindruck - vermieden ist.

Die Eurythmie ist dadurch etwas wie die musikalische Kunst selbst. Wie die musikalische Kunst nicht ihren vollen Wert erreicht, wenn sie bloß Tonmalerei ist, so werden auch die eurythmischen Bewegungen nicht das, was wir künstlerisch suchen, wenn sie bloß pantomimisch ausdrücken würden das, was in der Seele vorgeht. Das tun sie nicht; sondern geradeso, wie in der Musik das Wesentliche liegt in der gesetzmäßigen Aufeinanderfolge der Töne, in dem melodiösen Element, so liegt das Wesentliche hier nicht in dem unmittelbaren Ausdruck, sondern in der gesetzmäßigen Folge der Bewegungen. Eine äußerlich sichtbare Musik ist daher die Eurythmie. Und so ist es auch, dass nichts Willkürliches darinnen ist, wenn zwei Menschen oder zwei Menschengruppen, an verschiedenen Orten ein und dieselbe Sache eurythmisieren, eurythmisch darstellen, denn der individuellen Ausdrucksmöglichkeit ist nicht mehr Verschiedenheit gestattet, als wenn zwei Klavierspieler ein und dasselbe Musikstück nach persönlicher Auffassung wiedergeben.

Und dasjenige, was sonst unsere Sprache durchseelt an Lust und Leid, an Freude und an Enthusiasmus und so weiter, all das können wir auch durch die Formen und namentlich durch Gruppen darstellen — wobei die einzelnen Persönlichkeiten zusammenwirken durch die verschiedenen Bewegungen dieser Gruppen -, all das können wir hier auch in einer gesetzmäßigen Weise zum Ausdruck bringen. So ist es also eine stumme Sprache der Menschen in Bewegung, wodurch die Eurythmie wirken will.

Selbstverständlich muss alles Ästhetische im unmittelbaren Eindruck wirken, und ich sage Ihnen nur diese paar Worte voraus, damit Sie sehen, aus welchen Quellen, aus welchen künstlerischen Quellen diese Eurythmie geschöpft ist. Wie man in der Tat im Musikalischen eine innere Gesetzmäßigkeit der Töne in der Tonfolge, der Melodie und so weiter hat, so kommt man hier auf die Gesetzmäßigkeit der menschlichen Bewegungsmöglichkeiten selber.

Begleitet werden Sie das, was als stumme Sprache der Eurythmie vor Ihnen auftritt, auf der einen Seite hören von dem Musikalischen, das im Grunde genommen nur ein anderer Ausdruck ist, ein Ausdruck mit anderen Mitteln, begleiten[d] werden Sie hören auf der anderen Seite die Rezitation. Dasjenige, was in der Rezitation hörbar wird, wird in den bewegten Menschen auf der Bühne sichtbar. Beides wird parallel gehen. Eine Dichtung zum Beispiel wird rezitiert werden, also hörbar werden und die dichterische Kunst gleichzeitig eurythmisch vorgeführt - ein und dasselbe.

Nur wird dabei berücksichtig werden müssen, dass die Rezitationskunst, so wie sie heute betrieben wird, nicht gut zur Eurythmie verwendet werden dürfte. Denn heute berücksichtigt man in der Rezitationskunst— und sieht gerade darin das Große der Rezitationskunst - eigentlich den Prosainhalt der Gedichte, nicht das Rhythmische, das Taktvolle, das Reimmäßige, das zugrunde liegt. Das muss aber gerade bei jener Rezitationskunst berücksichtigt werden, die der rhythmischen Darstellung gerade dienen soll. Man muss also wieder auf die guten alten Formen der Rezitationskunst zurückkommen - und [so] wollen wir überhaupt wiederum für das Künstlerische eine Empfindung bekommen, eine bessere Empfindung wieder bekommen, als unsere heutige, etwas unkünstlerische Zeit. Unsere gegenwärtige Menschheit sucht im Künstlerischen auch vielfach den Prosagehalt einer Dichtung, den wortwörtlichen Inhalt in einem Gedichte.

Man braucht da nur zu erinnern, wie zum Beispiel Schiller, bevor er den wortwörtlichen Inhalt mancher seiner Gedichte im Sinne hatte, eine Melodie im Sinne hatte; und für diese Melodie, die nun in einer bestimmten Weise in seiner Seele lebte, suchte er dann erst den wortwörtlichen Inhalt. So sind die besten Schiller’schen Gedichte entstanden. Der wirkliche Dichter braucht eben das Formale, das zugrunde liegt dem Prosaelemente des Lebens.

Nun werden wir Ihnen zuerst aufzuführen haben eine Szene des ersten Teiles von Goethes «Faust». Da werden wir natürlich dasjenige, was gewissermaßen alltägliche Geschehnisse sind, entsprechend darstellen, wie man eben bühnenmäßig darstellt. Allein, der viel gesehen hat von den Versuchen, welche die Regiekunst der modernen Theatralik angewendet hat, um Goethes «Faust» in würdiger Weise auf die Bühne zu bringen, der weiß, wie schwierig es ist, dann dasjenige, was Goethe doch in den «Faust» hineingelegt hat, wirklich herauszuholen in der Darstellung, wenn Goethe, wie es ja auch an so vielen Stellen des «Faust» ist, in seine Dichtung hineinspielen lässt Übersinnliches, Geistiges. An vielen Stellen, wie Sie wissen - auch des ersten Teiles, insbesondere aber des zweiten Teiles des «Faust» — spielt Geistiges, Übersinnliches herein. Man kann die verschiedenen Regiekünste durchgehen, die angewendet worden sind: Es war wirklich viel geleistet, noch in den Achtziger Jahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts. Ich habe selbst in den Achtziger Jahren des vorigen Jahrhunderts Wilbrandt mit seiner liebenswürdigen Regiekunst, [der] den ganzen «Faust» auf die Bühne versuchte zu bringen, kennengelernt. Es war auch wiederum eine gewisse Vertiefung für die Interpretation [die] Mysteriendichtung, die [Devrient] auf die Bühne brachte und so weiter. Es ist ja viel versucht worden; allein immer bleibt etwas Unbefriedigendes gerade bei den Szenen zurück, wo Geistiges, Übersinnliches hereinspielte und dargestellt werden sollte.

Da versuchen wir nun, während wir nun das Übrige der Szenen rein bühnenmäßig darstellen, versuchen wir die «Geisterszene» durch Eurythmie gerade herauszuholen. Wir werden also jetzt vor der Pause rein bühnenmäfßig darstellen die erste Szene von «Faust», erster Teil, soweit dies in Betracht kommen kann. Also die Szene im Studierzimmer, die Pudelszene, wo also der Pudel stört den Faust beim Übersetzen der Bibel; und wo dann die Geister hereinkommen, da versuchen wir gerade durch diese stumme Sprache der Eurythmie wirklich in Bezug auf die Geisterszene aus dieser Weltdichtung herauszuholen, was in ihr liegt.

Goethe war sich bewusst, dass er viel so innerlich Menschliches in seine «Faust»-Dichtung hineingelegt hatte, dass er eigentlich selbst bis in die 20er Jahre hinein nicht daran gedacht hatte, den ersten Teil des «Faust» auf die Bühne zu bringen. Beim zweiten Teil war er sich dann bewusst, dass er den «Faust II» für die Bühne bearbeitet hat; aber der erschien ja erst nach Goethes Tode. Aber sehen Sie, der «Faust» war doch eine so gewaltige Weltdichtung, dass andere Leute darauf gekommen sind, den «Faust» aufzuführen, wirklich ihn auf die Bühne zu bringen. Goethe hatte nicht daran gedacht; für ihn war der Faust eben etwas innerlich menschliches Dargestelltes.

Mein alter Freund und Lehrer, Karl Julius Schröer, war sehr befreundet mit Laroche, der ein berühmter Schauspieler zur Zeit Goethes noch war. Laroche kam an der Spitze einer Deputation zu Goethe mit dem Vorschlage - es war erst Ende der 20er Jahre -, den «Faust» auf die Bühne zu bringen. Laroche berichtete dem Schröer: «Ja, da hat uns Goethe schön angefahren! Wütend wurde er, wie er hörte, wir wollten den «Faust» auf die Bühne bringen. Er sagte zu uns: «Ihr Esel'» Sie sehen, bei Goethe war schon ein rechter Zorn notwendig — und eine Überraschung. Denn Goethe, der dazumal wirklich schon ein artiger Herr geworden war, der «dicke Geheimrat mit dem Doppelkinn», der wurde nicht ohne Weiteres so unartig gegen so ausgezeichnete Leute wie zum Beispiel Laroche war, wenn er sie «Esel» nannte. Da musste er schon durchaus geglaubt haben, dass cs gar nicht möglich sei, den «Faust» auf die Bühne zu bringen. Er hat sich ja auch sonst öfter dann später darüber ausgesprochen.

Aber man hat - mit Recht - immer wieder versucht, den «Faust» auf die Bühne zu bringen. Wir glauben nun tatsächlich, dass man für gewisse Szenen das, was Goethe in seinen «Faust» hineingeheimnisst hat, durch das Zu-Hilfe-Kommen an einzelnen Stellen mit der Eurythmie herausholen kann. Auch das betrachten Sie, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, natürlich nur als einen Versuch; wie ich Sie überhaupt bitten möchte, dasjenige, was wir Ihnen heute noch vorführen können, als den Anfang erst der eurythmischen Kunst zu betrachten, die späterhin vervollkommnet werden soll.

Wir werden also zunächst, vor der Pause, den «Faust», erster Teil, erste Szene bringen, und dann nach der Pause Gedichte Dichtungen, Musikalisches, wo wir alles ganz eurythmisieren werden. In der «Faust»-Szene-Darstellung sind nur einige Stellen eurythmisiert. Aber im zweiten Teil unseres Programms werden wir Ihnen dann alles vollständig eurythmisch vorführen. Und da bitte ich Sie eben, die ganze Vorstellung so aufzufassen, dass Sie Nachsicht üben; denn wir sind mit der eurythmischen Kunst, die das will, was ich dargestellt habe, eigentlich erst im Anfange.

Wir glauben aber, wenn unsere Zeitgenossenschaft dieser neuen Kunst richtiges Verständnis und Interesse entgegenbringt, dass sie vervollkommnet werden kann, entweder noch durch uns oder durch Andere - wahrscheinlich das Letztere -, und dass dann einmal die Zeit kommen werde, wo sich diese Kunst, die den ganzen Menschen als Instrument verwendet, also das Höchste, was wir im Dasein haben, dass sich diese Kunst als vollberechtigte neben andere ältere vollberechtige Künste wird hinstellen können.