| 292. The History of Art II: “Disputa” of Raphael — the School of Athens

05 Oct 1917, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Every detail which we can lay our eyes on in order to understand this painting, to really understand it artistically, means every small detail has a certain meaning. |

| Let us be completely clear: under the papal predecessors before Julius II, Rome was at the time basically completely different than during Julius II's reign. |

| There they remained. One can really not understand what happens in the becoming of being human beings when one doesn't have a clear understanding of the need to repel spiritual impulses towards the East—to what is connected to Asia and to Russia as a European peninsula—from the 8th and 9th Centuries. |

| 292. The History of Art II: “Disputa” of Raphael — the School of Athens

05 Oct 1917, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

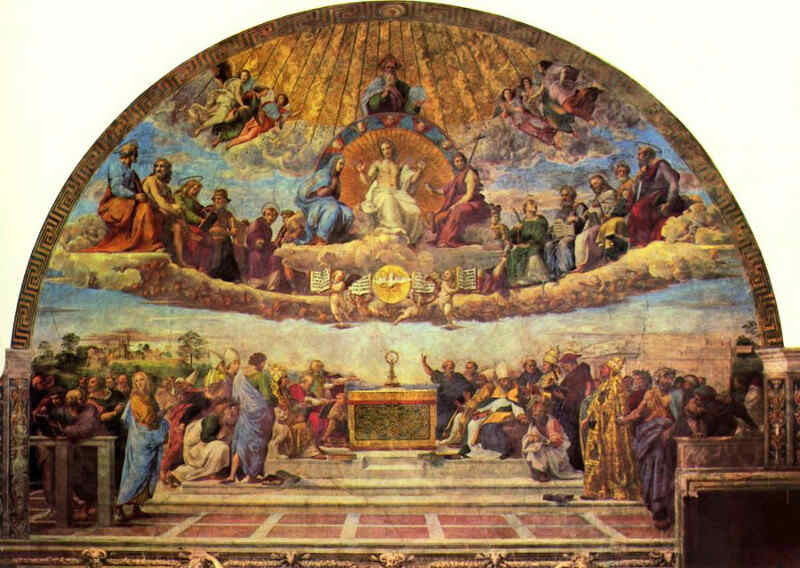

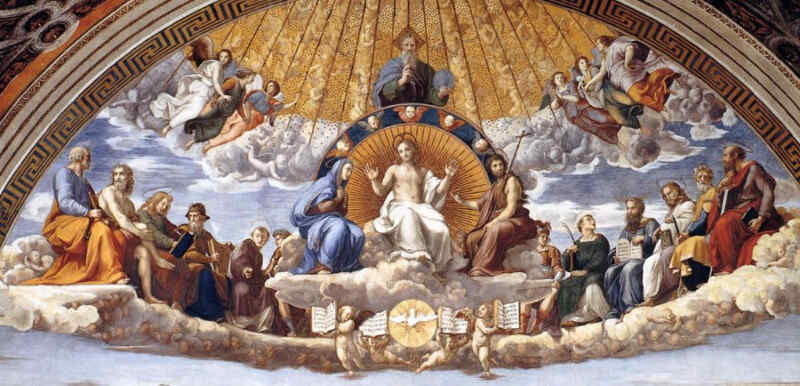

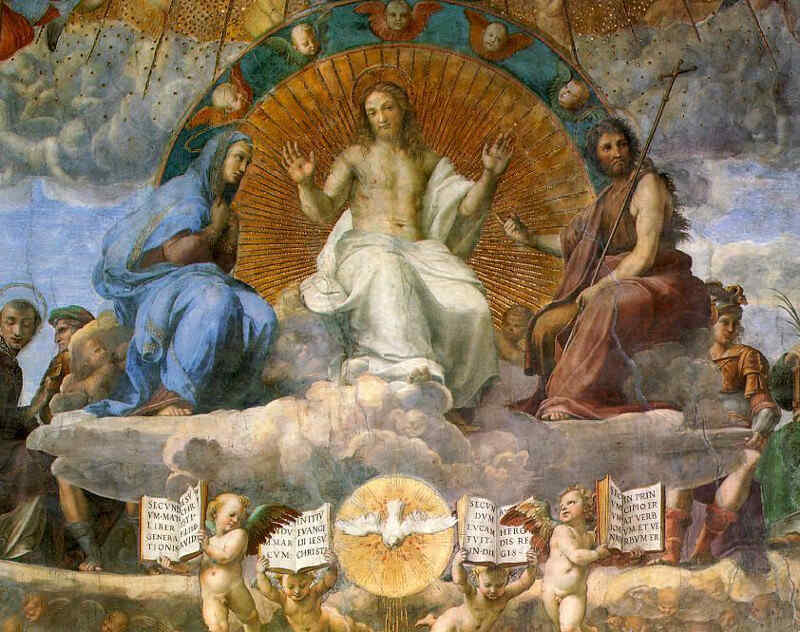

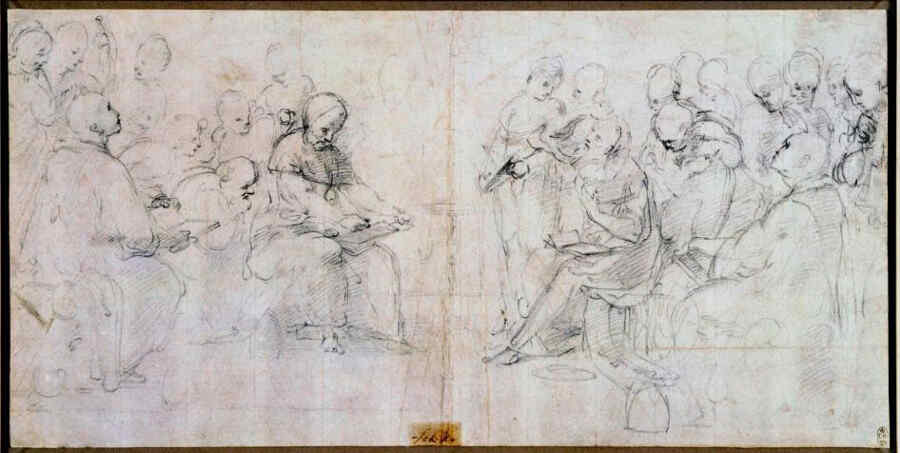

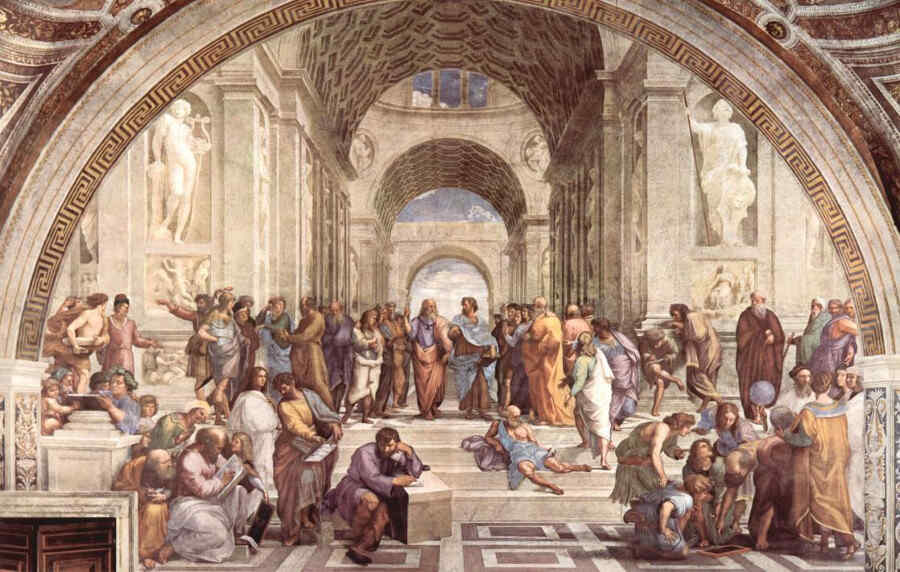

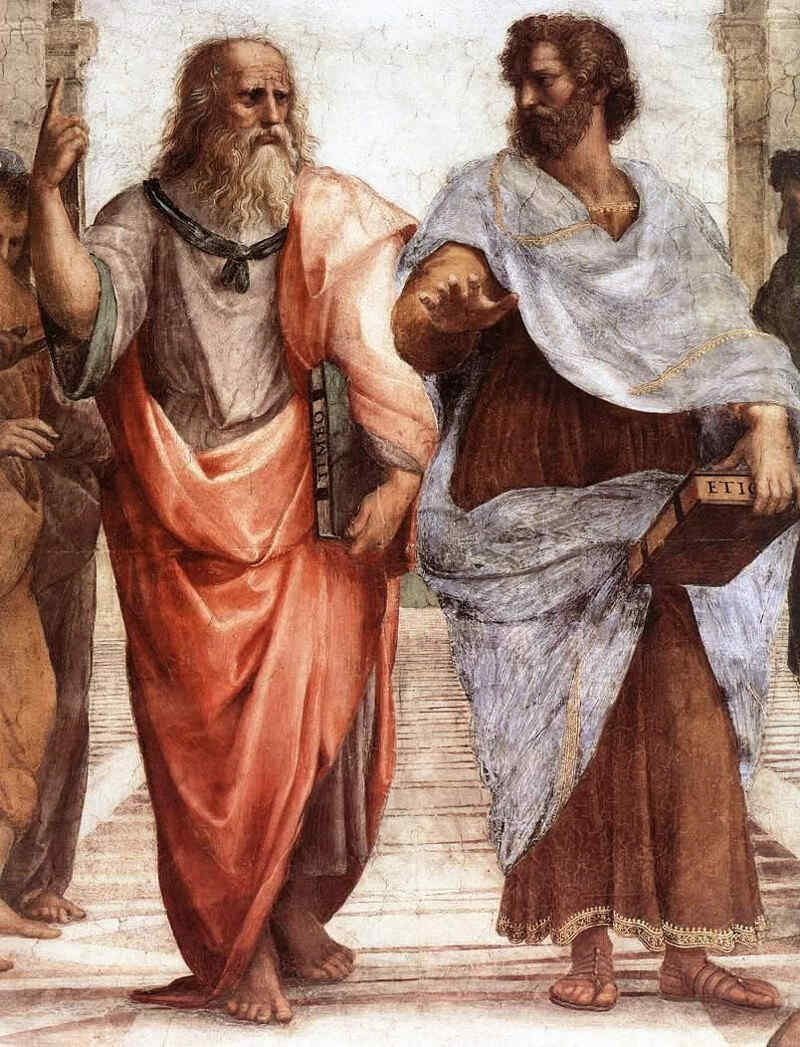

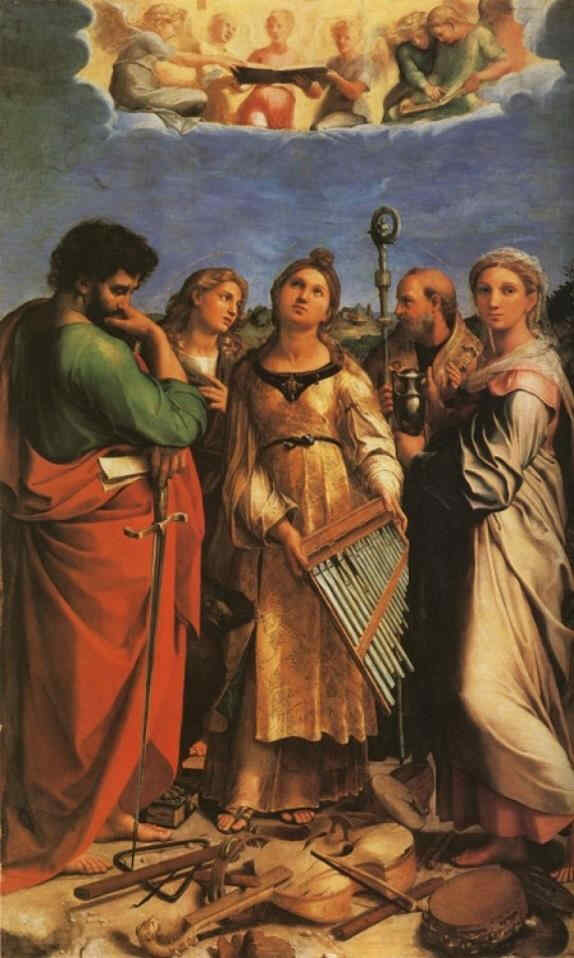

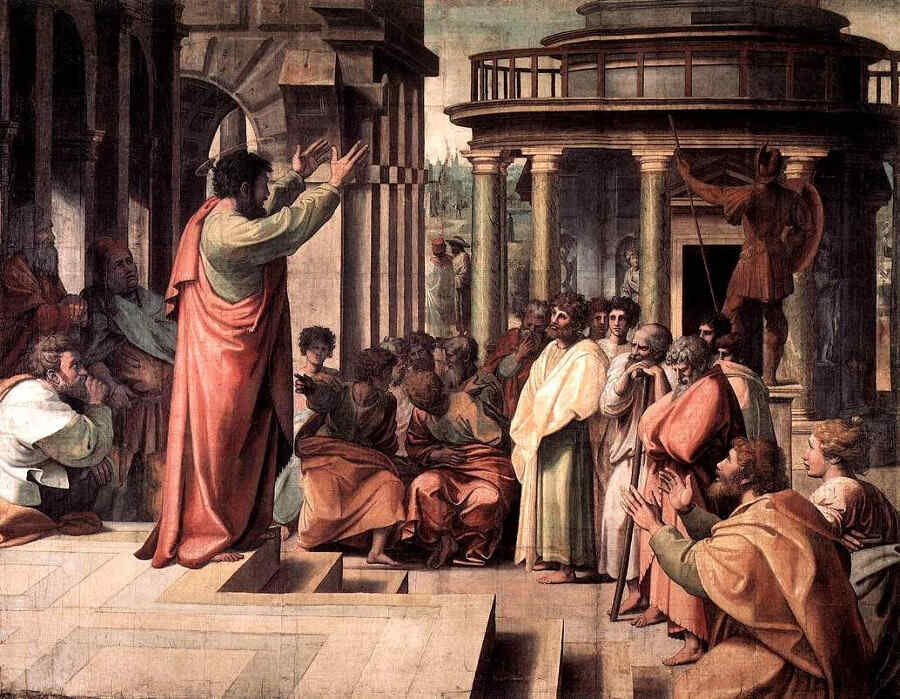

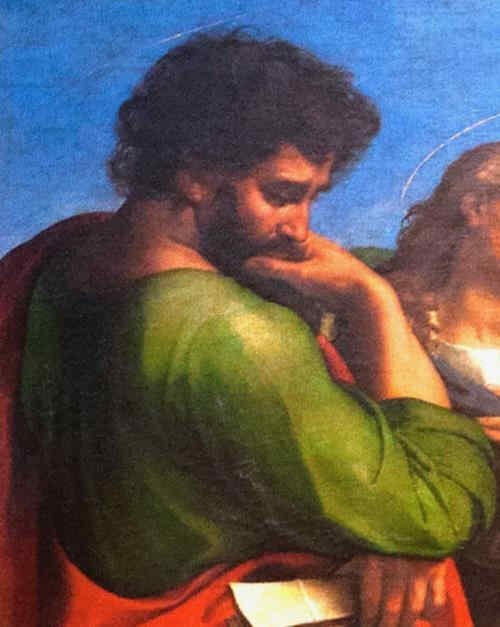

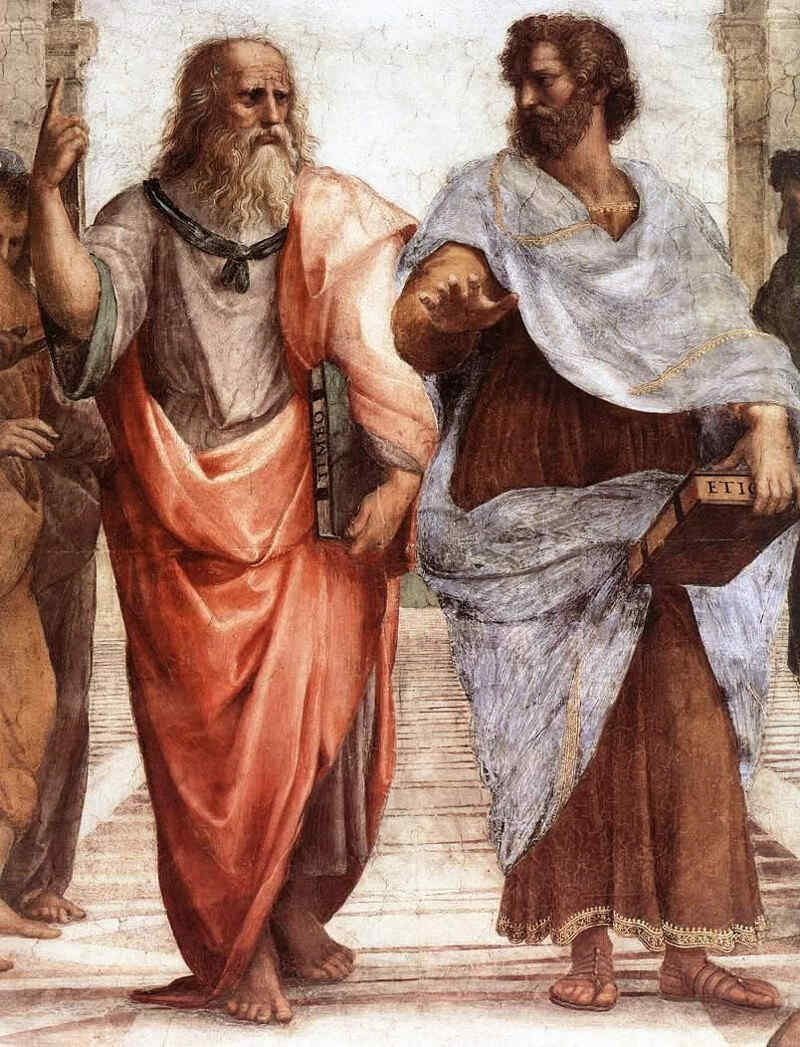

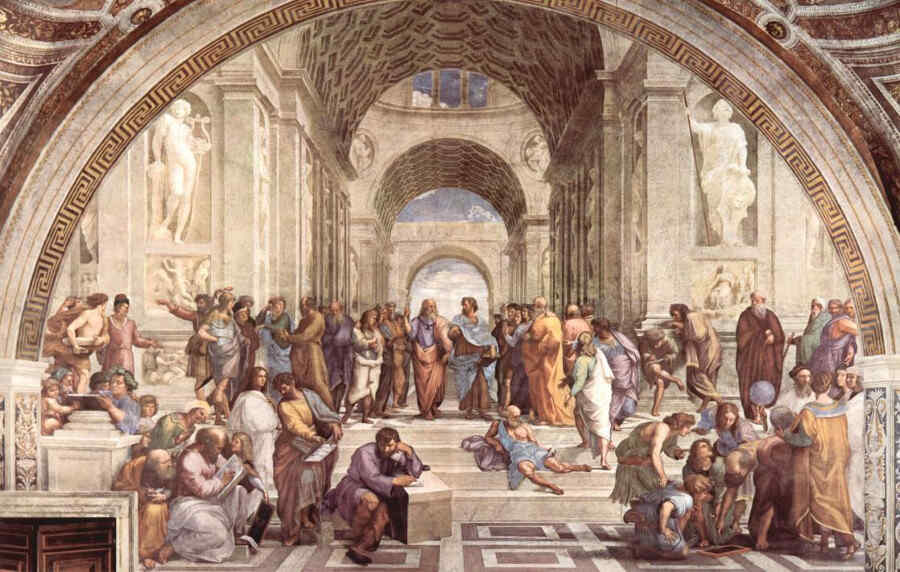

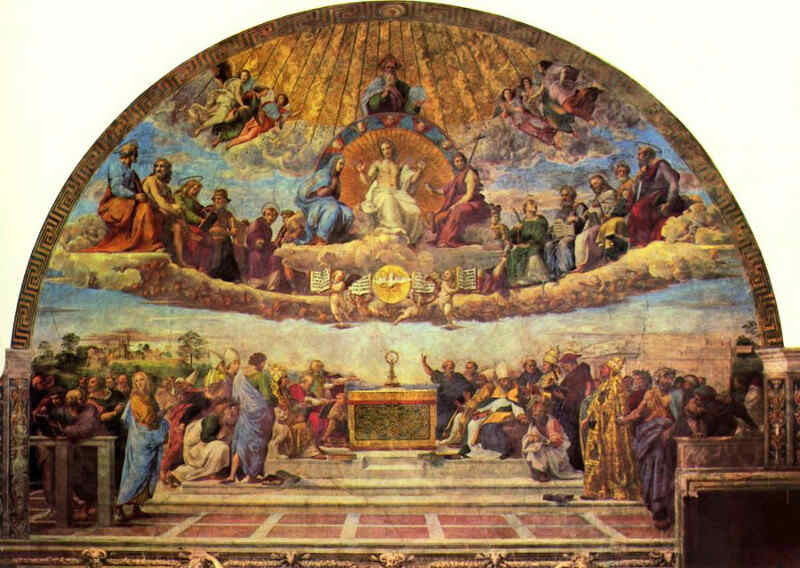

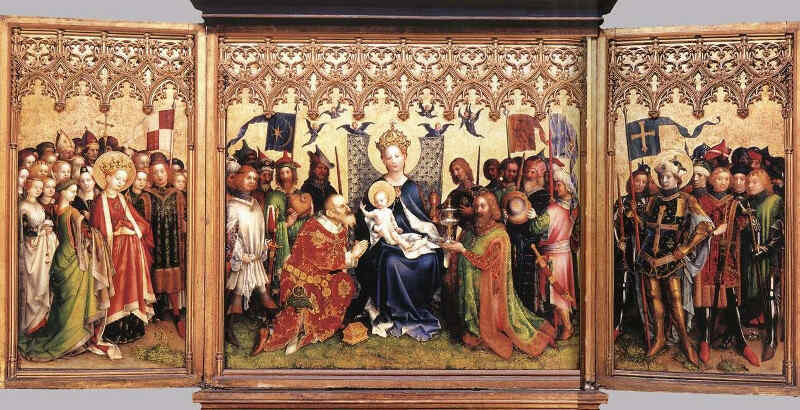

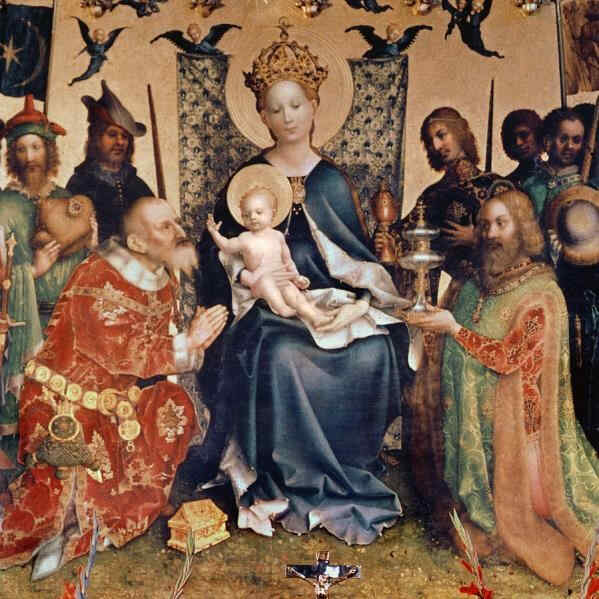

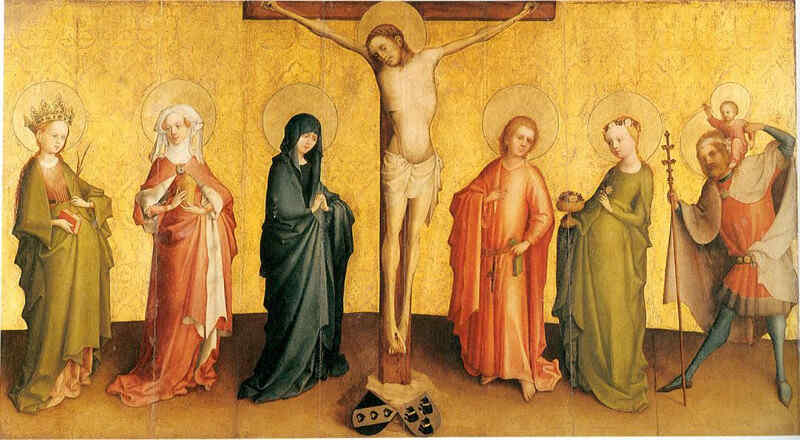

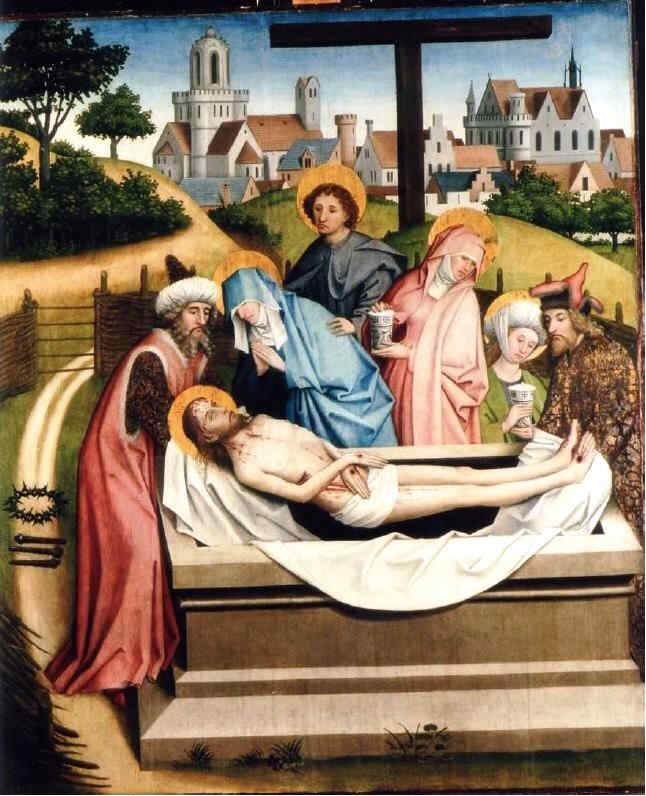

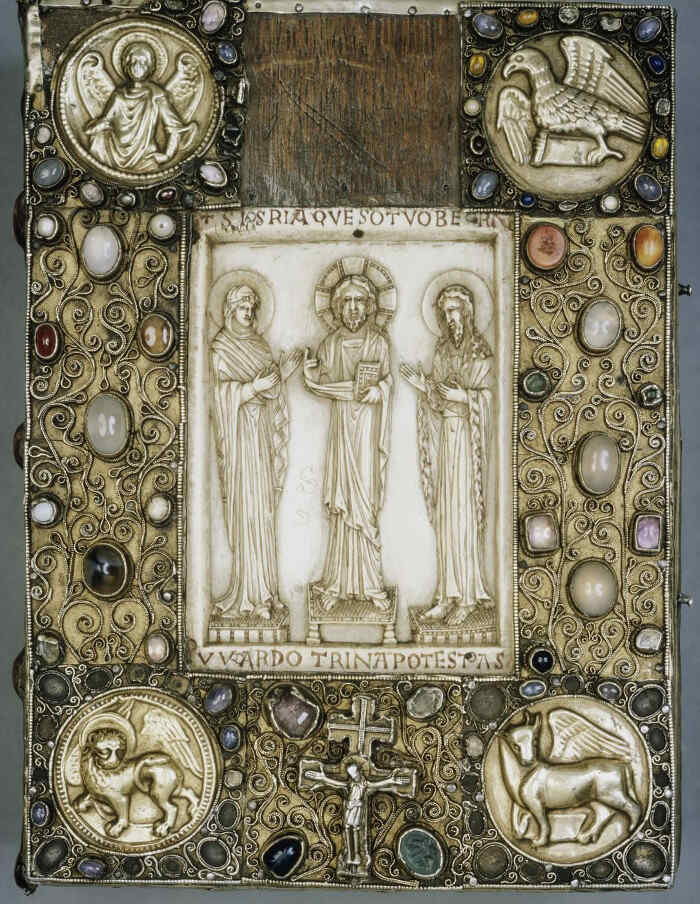

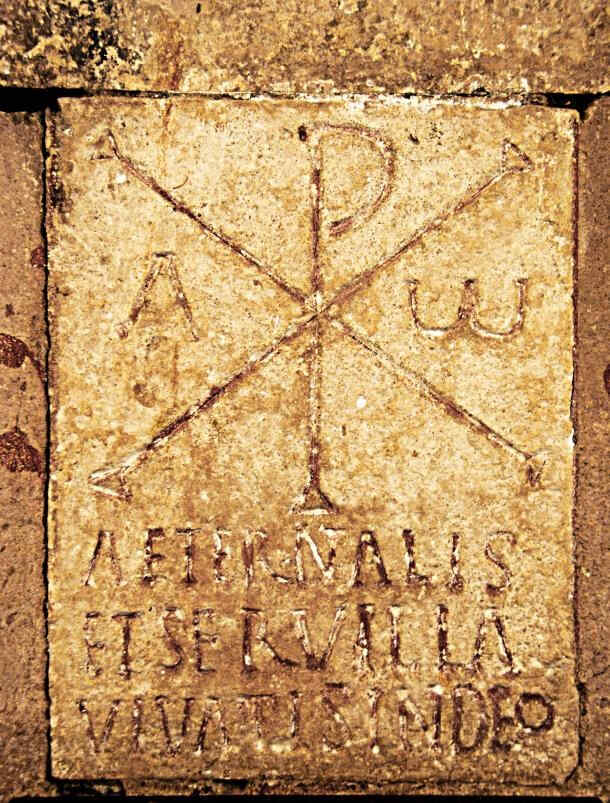

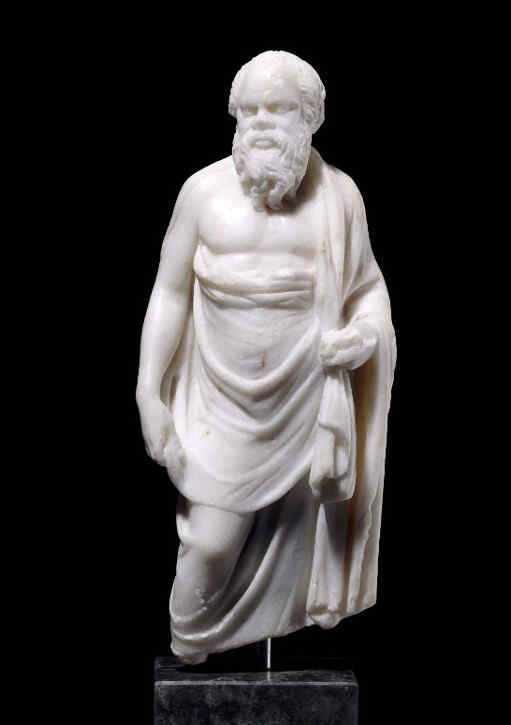

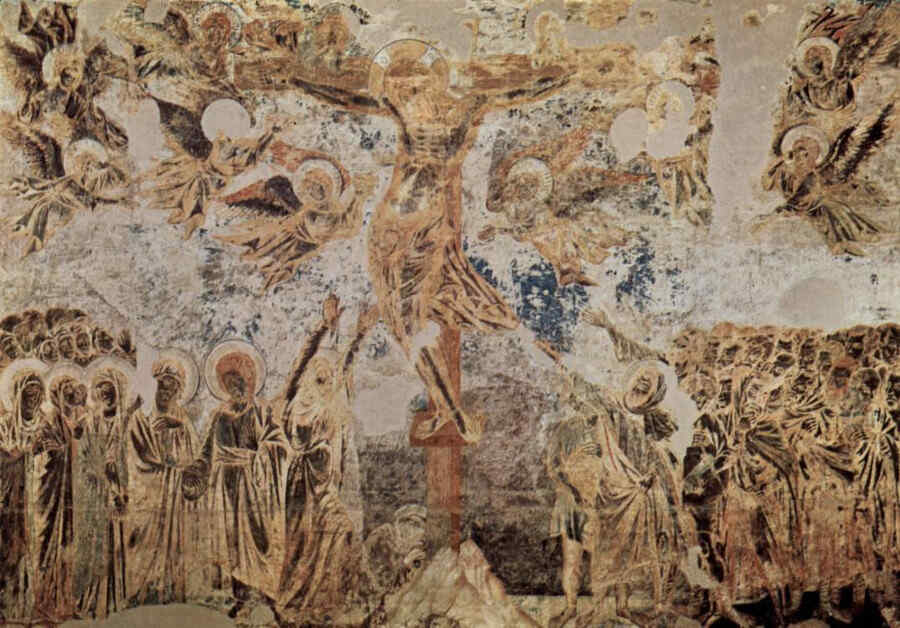

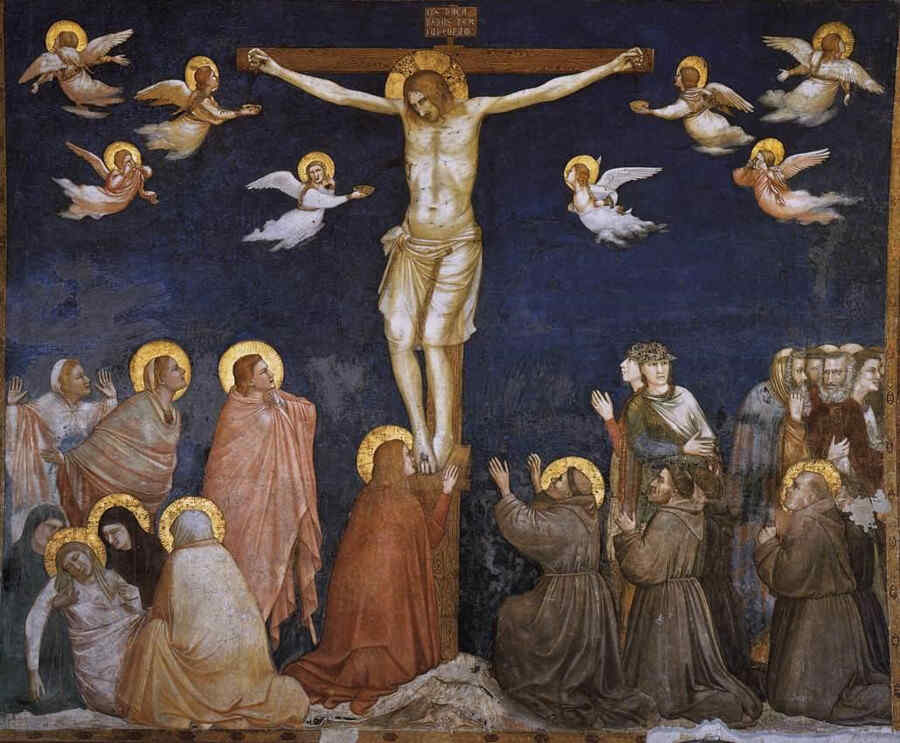

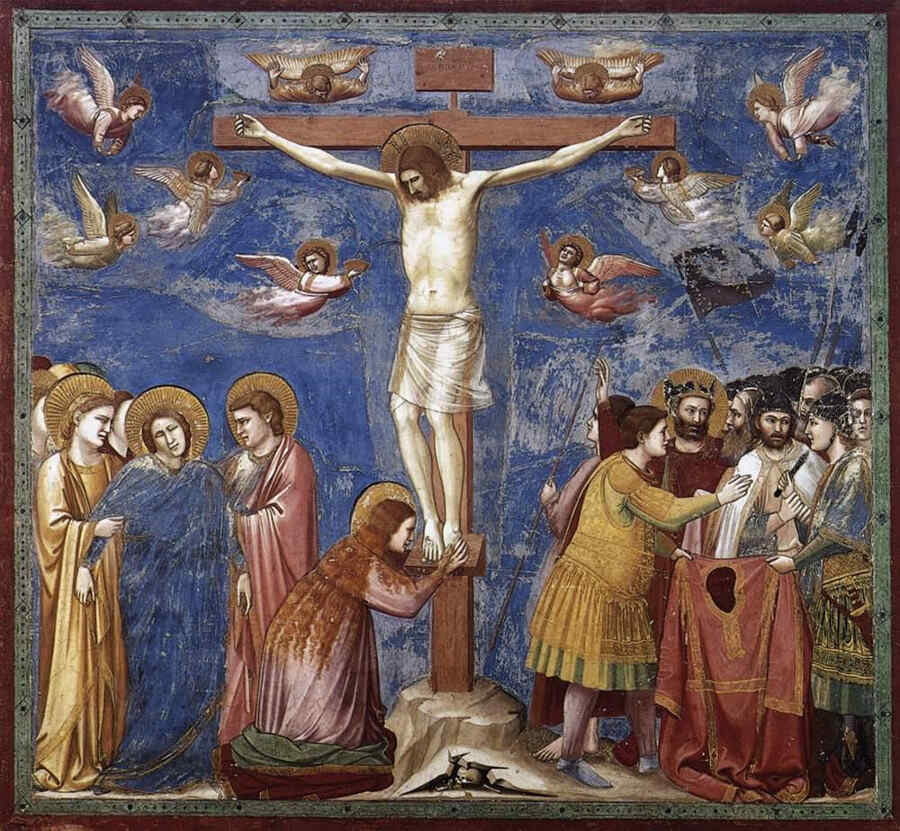

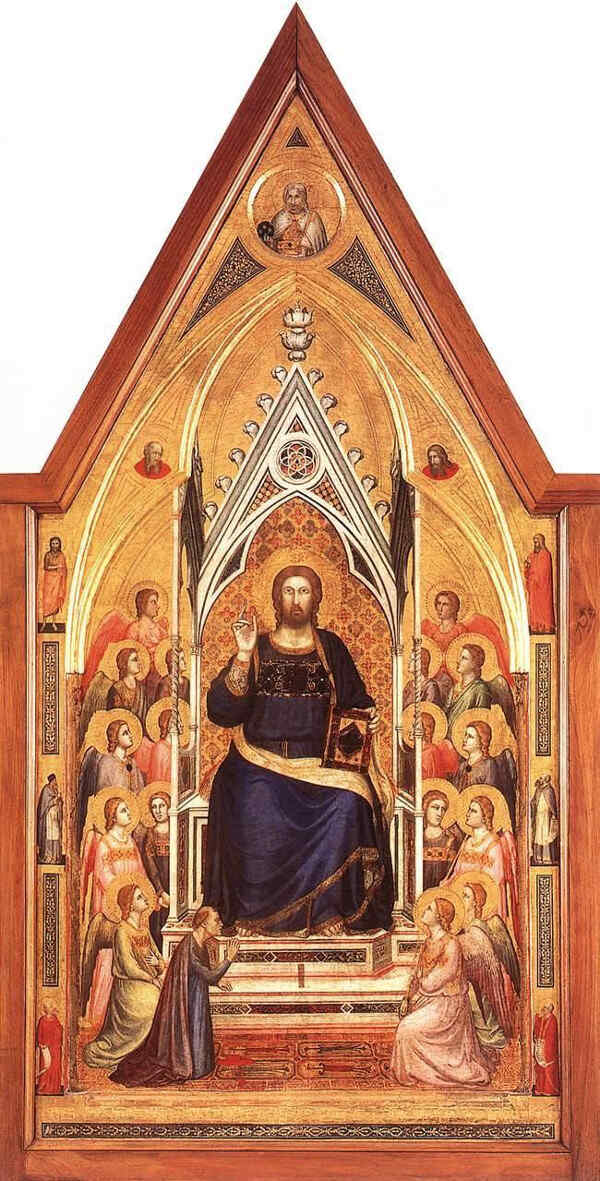

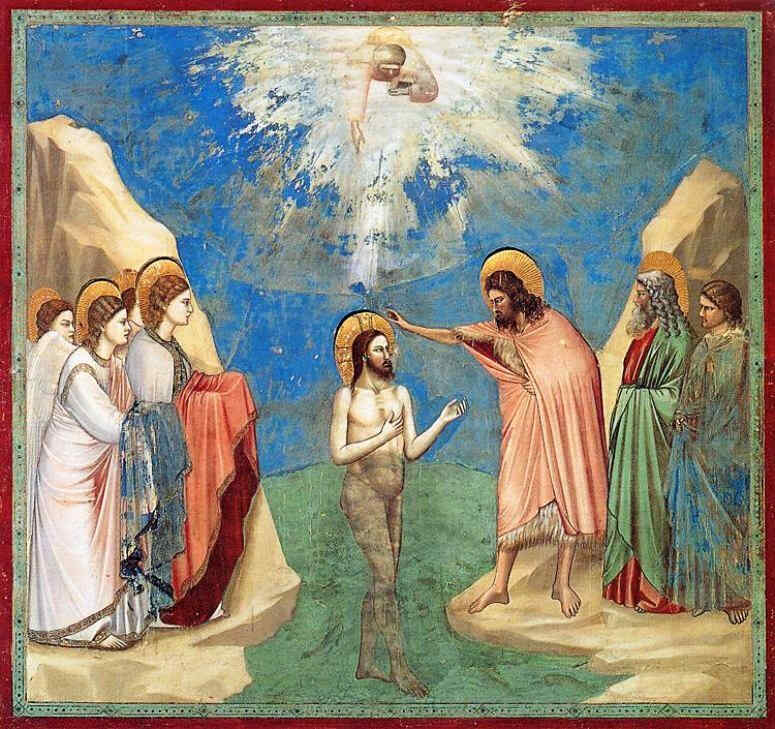

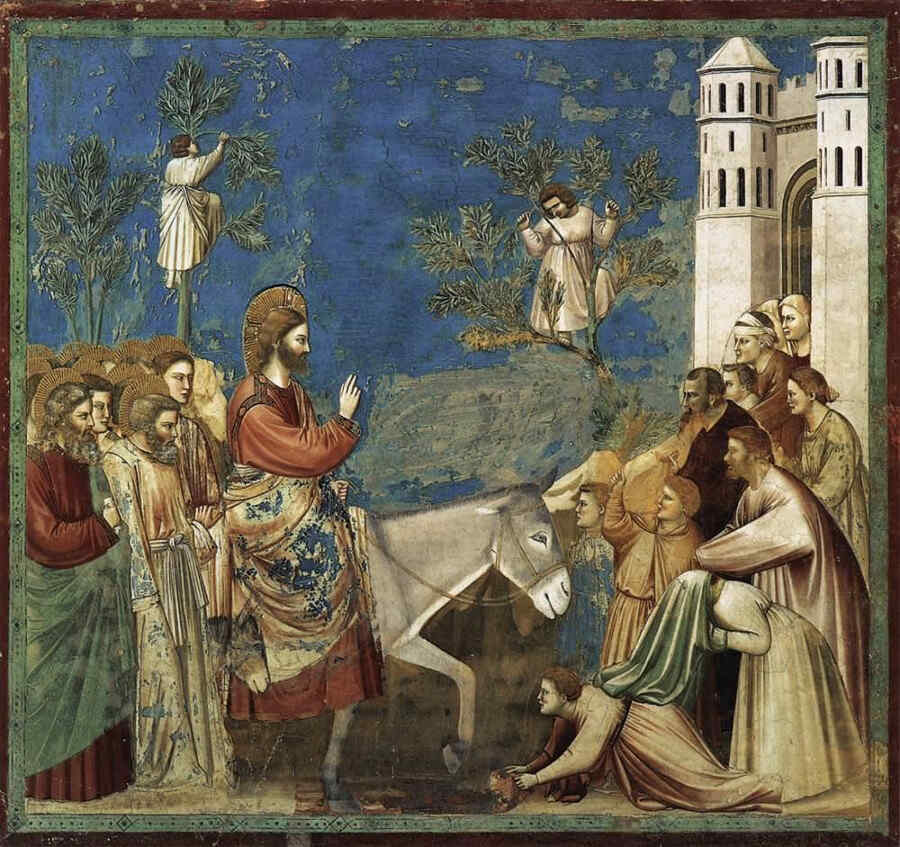

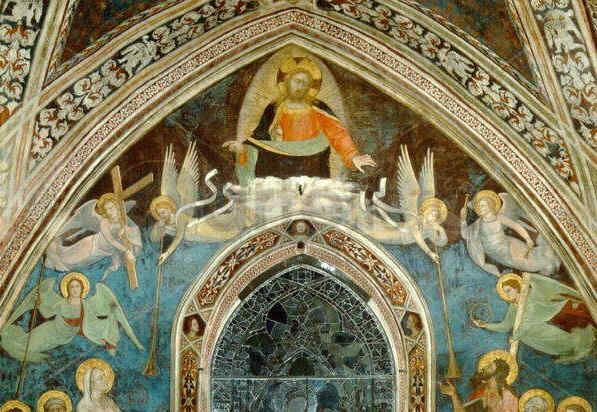

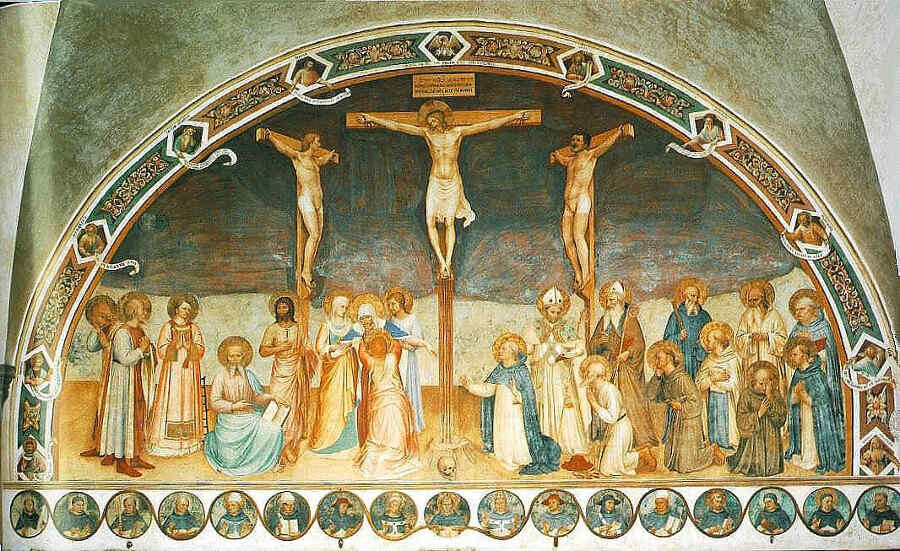

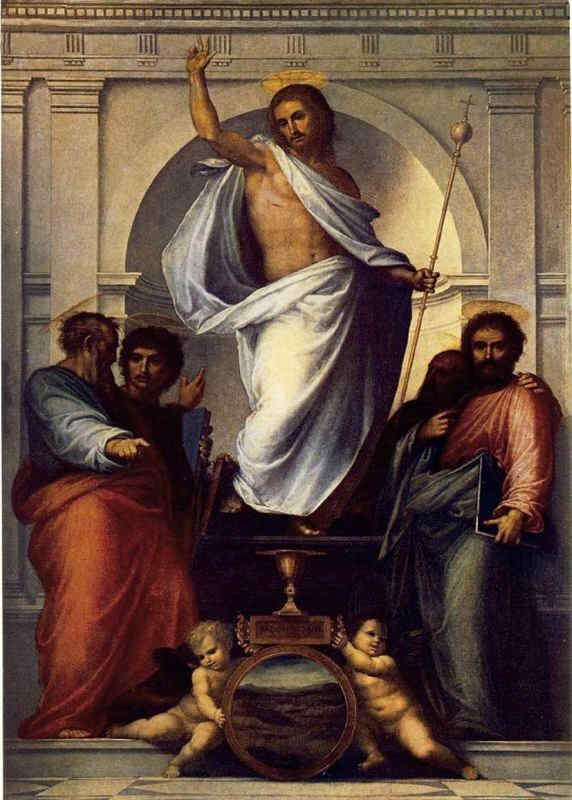

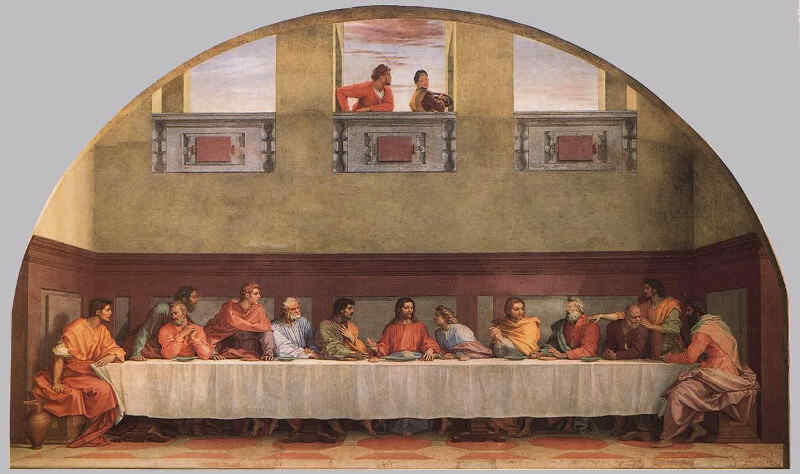

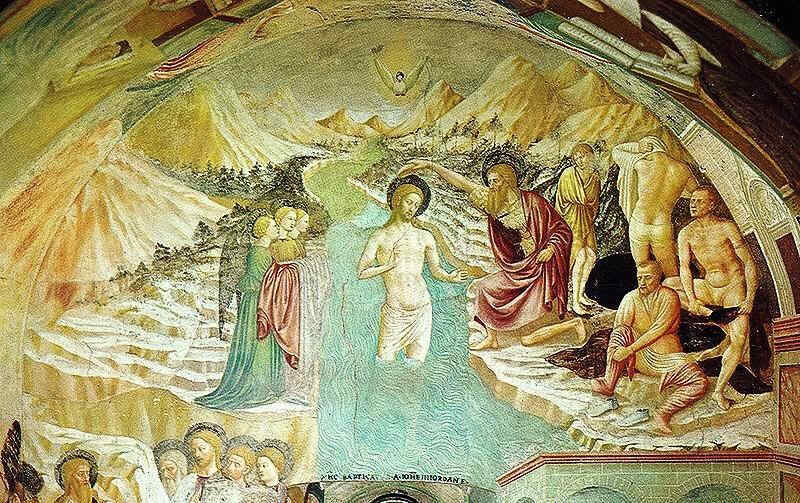

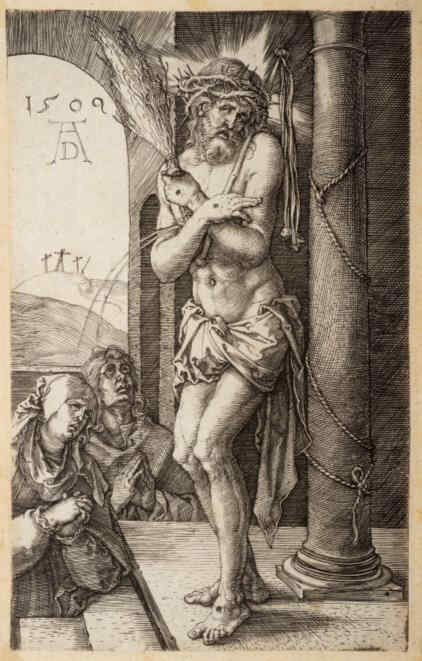

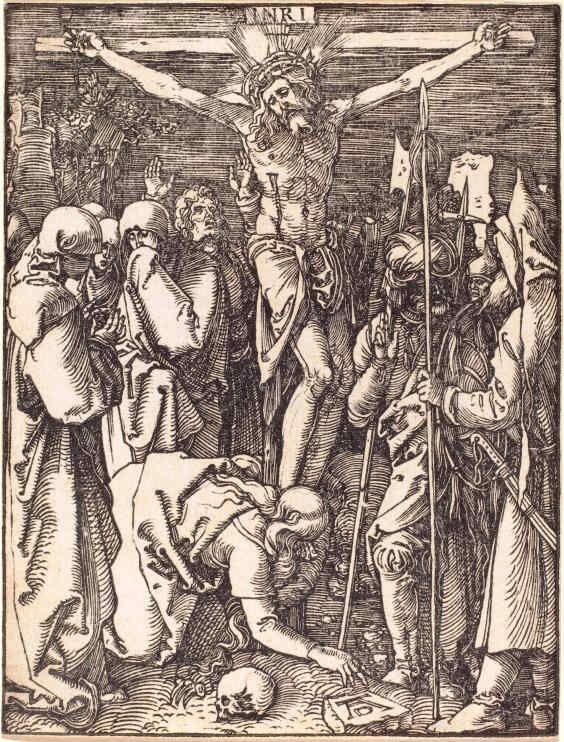

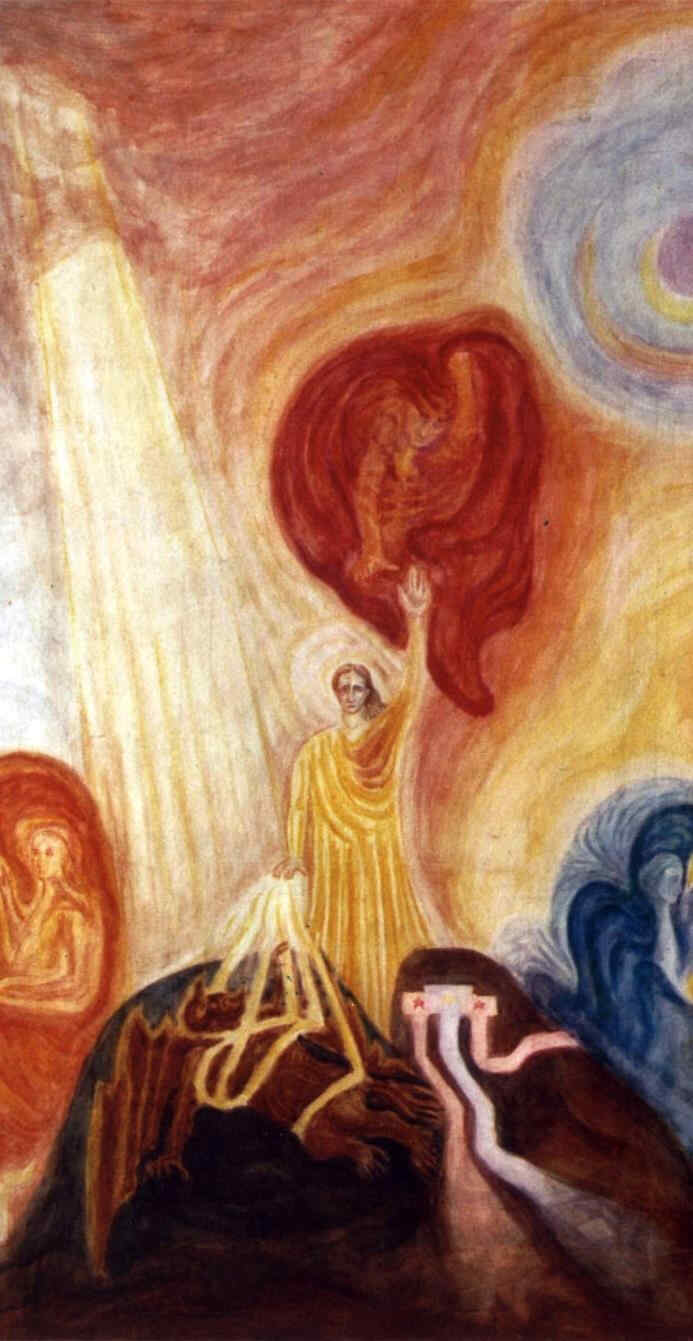

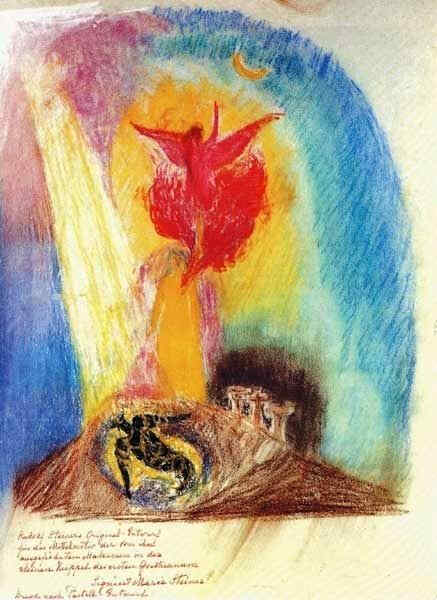

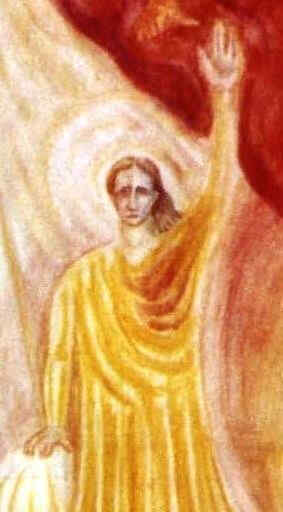

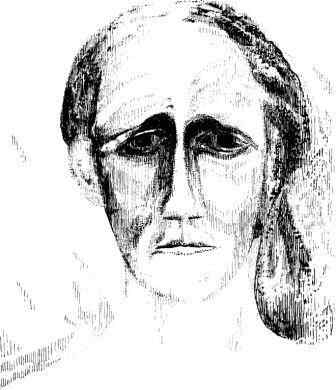

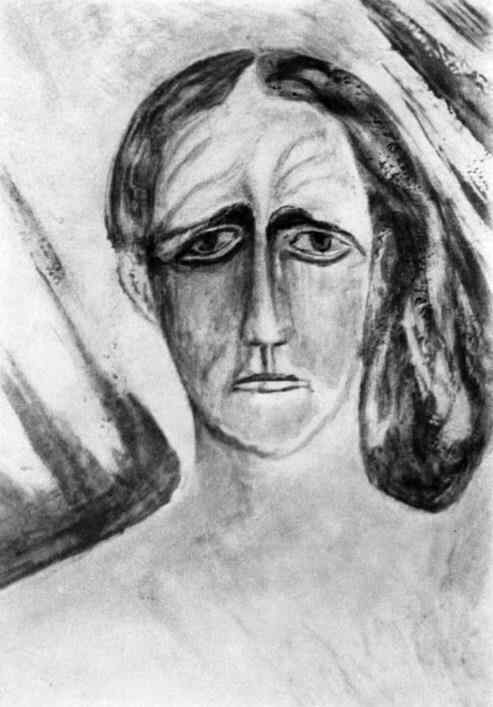

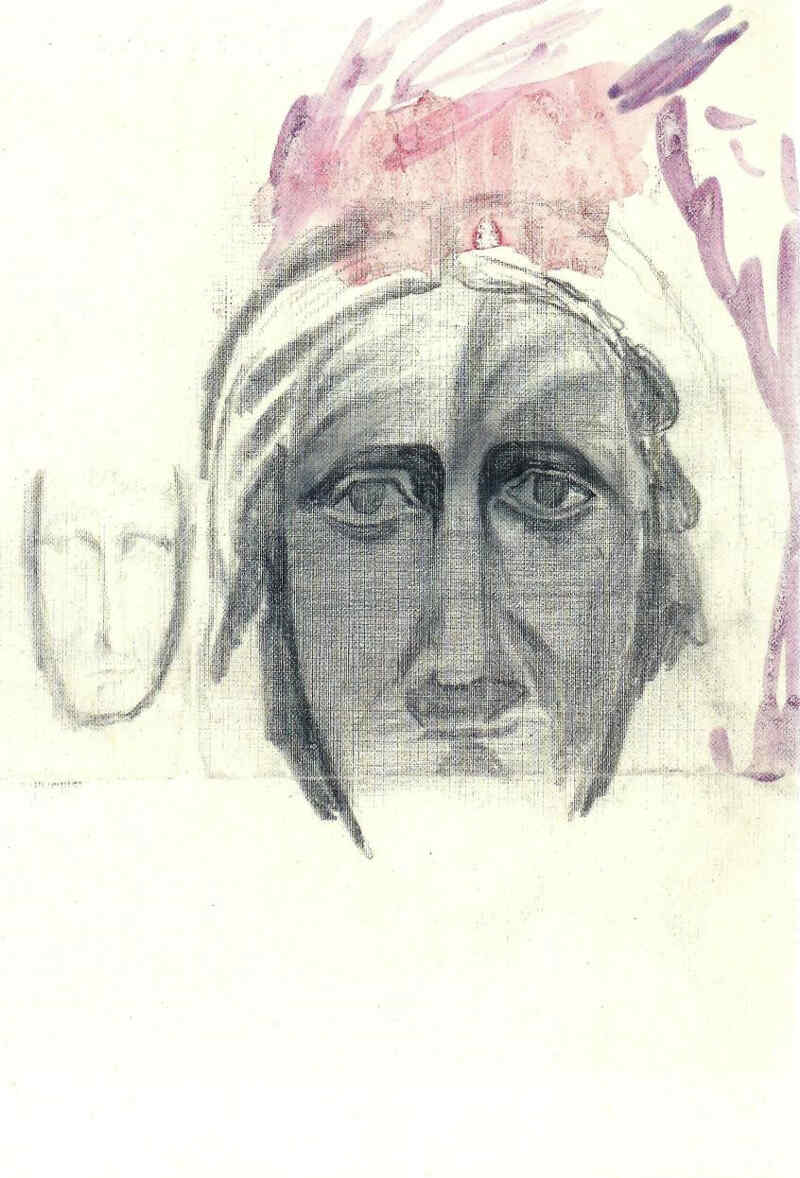

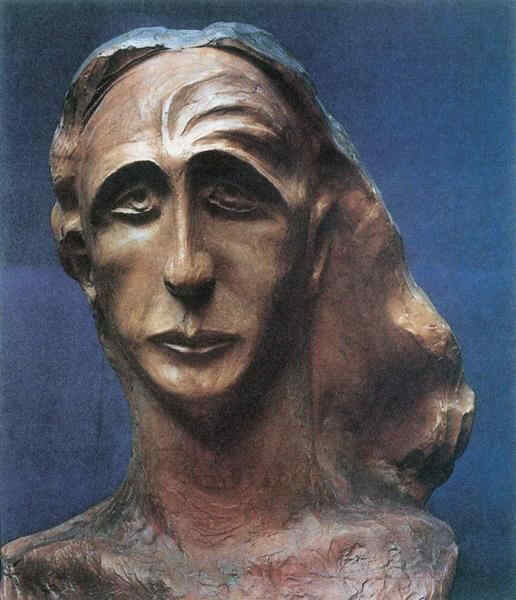

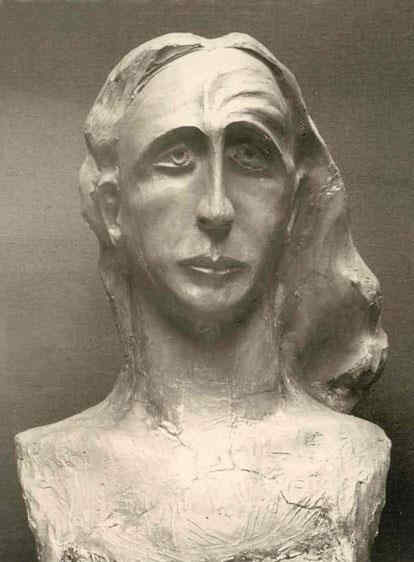

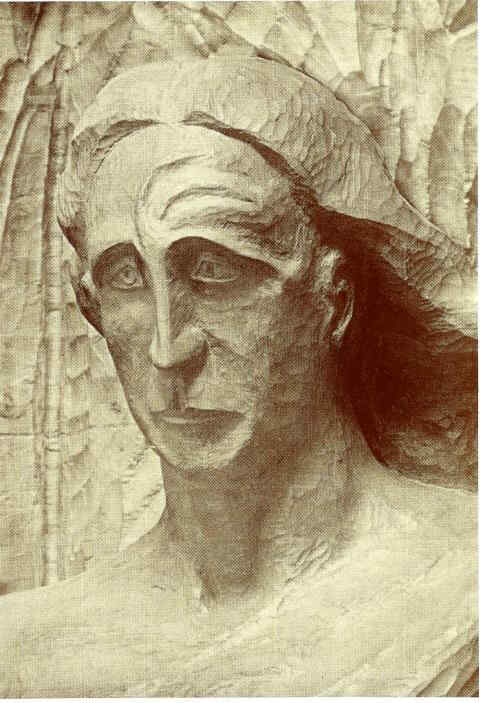

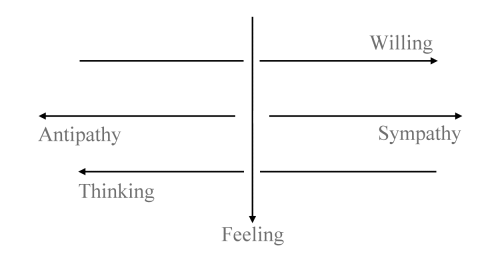

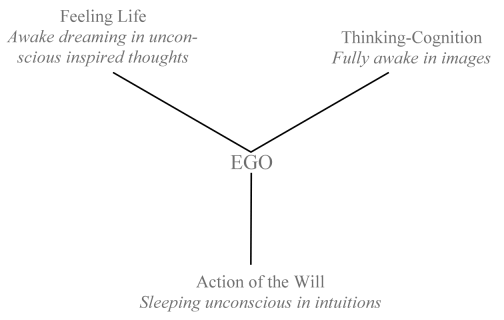

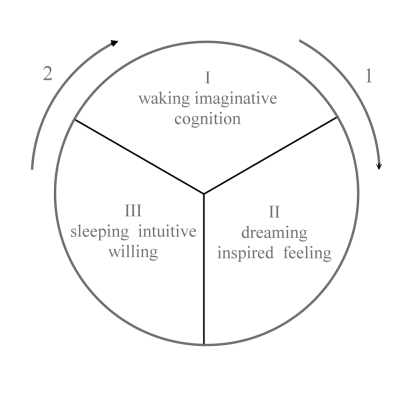

I didn't want to use several images as an introduction to my art history lecture today, but limit our observational introduction to only two images, both which will be placed into the newer historical development of mankind. We will then link these to the introduction of cultural epochs as we have done in earlier years. Look at this first painting to which our primary observation will refer; a painting you know well, the so-called “Disputa” of Raphael.  Let us visualize the painting's content briefly: below, in the centre, we see a kind of altar with a chalice on it and the host, a sacramental symbol. To the left and right are religious individuals and we recognise them as teachers, popes and bishops according to their drapery. Opposite the middle, the group is seen as moving from left and right according to the hand gesture of a person directly right of the altar. According to this we observe that these individuals are taking part in something descending from above. As a result we see, by looking at the space close behind the altar where the group is positioned, into the landscape and directly above it—in the upper half of the picture—cloud masses accumulating. To some extent we see the infinite horizon within this space. From out of the middle of these cloud masses we see angelic genii rise, floating on both sides of the dove, bringing the Gospels, transported out of the undeterminable spiritual world. In the centre we can see the Holy Ghost depicted in the symbol of a dove. Above the somewhat receding Holy Ghost we have—clearly, the angelic figures carrying the Gospels are actually coming forward in perspective—the figure of Christ Jesus and above Him the figure of the Father God. Thus we have the Trinity above the chalice where the sanctuary is found. On both sides of the Christ figure we have corresponding groups; a heavenly group above, reflected below by the worldly group. On both sides of the central Christ figure appear Saints, the Madonna on his right and John the Baptist, followed by others: David, Abraham, Adam, Paul, Peter and so on. Still further up rising into the clouds are actual genii figures, spiritual individualities. This image we have in front of us now—of course there are much better copies available—I would like to link this to the evolution of mankind. Primarily we need to clearly distinguish between what is given here and what we can experience when we transport ourselves into the feelings of the time when this image was actually being painted. If we shift ourselves into the 16th Century and compare it with the complexity of sensations a painter would paint in, today, we need to say: at that time, in Rome, when Pope Julius II reigned and what worked in him as Julius II in the middle of his twentieth year to call Raphael to Rome, was at that time, and in every town, the human experience of something which lived as a deep truth depicted in this painting. Today of course something similar could be painted; but if it was to be similar to this painting in the scene design, it would not depict any true reality. Such things need to be made completely clear otherwise one will never arrive at a concrete observation of human history but forever remain in abstract observations of a legend—a bad saga—which is called the history today in schools and universities. Every detail which we can lay our eyes on in order to understand this painting, to really understand it artistically, means every small detail has a certain meaning. Just think how Raphael, this extraordinary individuality Raphael, about whom we have often spoken, how he arrived in Rome. He too was in a body of a twenty year old and one can easily conclude that while he was mainly painting this picture, he was approaching the end of his twenties. At the time he was completely under the influence of two old people who had already experienced two great battles in life and who had plans and ideas, ideas who everyone, one could say, considered as most far-reaching. Let us be completely clear: under the papal predecessors before Julius II, Rome was at the time basically completely different than during Julius II's reign. The most remarkable here, as predecessors, were the Borgias. One could say that during the time of Alexander VI Rome was gradually being developed as overlapping the old ruins and rubble work of the ancient world where the Church of St Peter almost expired and became impractical. Admittedly these people were filled with a certain nostalgia for the artistic immensity of antiquity and wanting to enliven it again. However, a strange incident happened between the Borgias and Julius II, just at the turn of the 15th into the 16th century. Beneath the room and hall which belonged to the Camera della Segnatura, Alexander VI had two frescoes painted which we want to talk about today. It is surely extraordinary that Julius II, the patron of Raphael, had shunned this lower room which had been the ordinary residence of his predecessor, as if ghosts of cholera and the plague circulated there. He shunned this completely, could not be bothered with artistic or any other events which had taken place there before. On the contrary he decided, according to his ideas for the rooms and halls in the upper storeys, to spruce them up as we can still see them today. We must just think of the mind-set of Pope Julius II in connection with the beginning of the 16th Century and how his mind worked quite differently to those of his predecessors. The other patron of Raphael was Bramante. He had a plan in his head for the new St Peter's Church. Both Julius II and Bramante were already old people, as I said, who had the storms of life behind them. They called youthful individuals like Raphael to Rome to serve them, bring to expression picturesquely the new ideas powerfully rumbling in their heads, new impulses which they thought should penetrate humanity. One should look more closely at these impulses that originated in Rome and were to penetrate humanity from the beginning of the 16th Century onwards. These impulses depended from the one side on the close connection of the development of the outer Christian ecclesiastical world and then again, what the establishment of the Christian ecclesiastical world would relate to. On the other side it relates to the entire historic development of the western world. Just think for once, that today's human being has great difficulty in transporting his feelings and thoughts into a time, as it were, that have developed out of this image, so often named the “Disputa”. Even more difficult it is for contemporary mankind to transport themselves into centuries further back when Christianity already had power. I have often mentioned that people today have the impression that mankind were always as they are today. That is not quite the case, particularly in relation to their soul life, they were not like now. Just as with almost two thousand years before the Mystery of Golgotha something had been inserted into human evolution beside this Mystery which has spread into the breadth of social evolution, so something quite different to the Mystery of Golgotha came forth which we understand in a different way today. People imagine far too vaguely that at the time when this image was created, mankind was subjected to the discovery of America towards the end of the 15th century; secondly the entirely different social understanding came about through the invention of printing which finally, through Copernican and Kepler viewpoints established a new science. Just look at this painting. I want to say: if a painter would paint it today it would not in the same sense of truth be what it was then, it can't be; because today one couldn't find the soul who would paint this image in the same sense as at that time when it was actually painted, who would objectively with such an imagination for the earth have been thus, as if America hadn't yet been discovered. These would be souls who look at up at the clouds with true faith, who imagine the spiritual world in the clouds as we imagine it today, who to a certain extent imagine the clouds as real spatial bodies. Such souls are no longer to be found today, not even amongst the most naive. However, we imagine the souls of those times incorrectly if we don't believe that the content of this painting was something directly reflected by them. Let us consider—what exactly is the content of this painting? Out of today's scientific viewpoint we could identify the content of this image: we are accustomed to say that Imagination is the first step to looking into the higher worlds. If we say: up to the 16th century mankind had a view regarding the world and cosmic space in relation to the earthly world, which depended on imagination, then this is the actual truth. Imaginations were at that time something lively; and Raphael painted lively representations of soul experiences. The view of the world, the world image, was still at that time something imaginative. These imaginations were dispelled by the caustic power of Copernicanism, the discovery of America and the art of printing. From this time mankind took the place of imagination, what we call imaginative knowledge and imaginative perception, and replaced it with outer representational images of the world's construction in totality. Thus, while presently we imagine the sun, the circling planets around it and so on, the people then couldn't do so at all; when they wanted to speak about something similar, they spoke about imaginative images. A representation of such an imagination is this painting. In the centuries in which imaginative cognition developed gradually to allow such paintings like those Raphael made, came to a certain cessation in the 16th Century, these centuries are thus the 16th, 15th, 14th, 13th, 12th, 11th, 10th right back to the 9th Century, but no further back. If we want to go yet further back we won't find any real imaginative representations any longer if we ourselves want to experience imaginative art, as people did in these mentioned centuries, which we find difficult enough to raise in the soul today, imaginatively. If we wish to experience what Christianity was before the 6th Century we need to imagine the Christian experience as far more spiritual than we tend to do usually. Augustine extracted only what he could use from the Christian imaginations. Yet by reading Augustine today one gets quite a different feeling for what else lived as a world view and as an image of the interconnections of the world with humanity at that time, so different from now. Of particular importance are the ideas which you find on reading Scotus Erigena, who taught at the time of Charles the Bald. One might say that these ancient centuries before the 9th were permeated with Christian thoughts experienced by those who at least elevated their thoughts to permeate their Christian thinking with highly spiritual imagination. One might say when humanity created a world view during these ancient times they included really very little of their direct sense experiences. From their world view they included much more of that which did not result from sense experiences but had been brought about by old clairvoyant sight of the world. When we go back to the first centuries after the Mystery of Golgotha and follow the Christian ideas then we find that these ideas are such than one would rather say—these people were interested in the heavenly Christ, the Christ as He was in the spiritual worlds, while what He became on the earth below they considered more as supplementary. To search for The Christ amidst spiritual beings, to think of Him in relation to super-sensory spirituality was their essential striving, and that came out of the old spiritual—then the atavistic—world view. This world view filled the ancient culture right down to the third post-Atlantean age. At that time it was thought that the earth really was some kind of supplement to the spiritual. One should familiarise oneself with an imagination which is entirely essential if one would understand, would want to comprehend, how humanity actually developed from that time to now. With this imagination we must acquaint ourselves with the idea that the Europeans had by necessity to drive back spiritual imagination for the unfolding of their culture. This should be dealt with in sympathy and not antipathy—this should in no way be judged with a critical mind but the facts should simply be taken as they are presented: it was simply the fate, Europe's karma to acquire their culture in a way they had to. It was Europe's fate: pushing back spiritual ideas, curbing it so to speak. Thus it became ever clearer and more meaningful that from the 9th Century Europe needed Christianity while spiritual ideas were being suppressed. A result of this necessity was the splitting of the Greek- oriental and the Roman Catholic Church. At that time it split the East from the West. This is very important. The West had the destiny to push spiritual impulses into the East. There they remained. One can really not understand what happens in the becoming of being human beings when one doesn't have a clear understanding of the need to repel spiritual impulses towards the East—to what is connected to Asia and to Russia as a European peninsula—from the 8th and 9th Centuries. These impulses were pushed together and developed independently from western European and central European life, and propagated into the present Russia. This is very important. Only once this was properly established. Today there is a tendency not to consider things through relationships. As a result an event such as the Russian revolution apparently developed in a few months—someone or other came to this idea—while the truth pre-empting it lay in the background as a result of the specific course of events through the centuries, while spiritual life became invisible, impractical and pushed back towards the East and being stuck, yet still working in a chaotic, indefinable way made people stand right within events in the East. Yet this standing within it was really hardly living within it just like people who swim in a lake—if they have not exactly drowned—have seawater surrounding them. Likewise, what worked as spiritual impulses superficially in the East, still existed spiritually. People swam inside it and had no clue what pressed in on the surface from the 9th Century and which was then pushed back to the East, so that it could be safe guarded to survive and enter evolution later. People who originated in the East and who gradually developed from migration and similar relationships, into their souls the spiritual impulses were introduced which couldn't be used in the West, South and Central Europe. The West retained something extraordinary. The East, without knowing—most important things run their course in the subconscious—the East, without knowing, remained steady on the basic saying of the Gospels: “My Kingdom is not of this world”. Hence in the East the leaning within the physical plane is always upwards, towards the spiritual world. The West depended on reversing the sentence: “My Kingdom is not of this World” by correcting it to make the Kingdom of Christ in this world. As a result we see Europe had the fate of constituting the realm of Christ outwardly as an empire on the physical plane. One could say from Rome the law was proclaimed since the 9th Century: break away from the sentence “My Kingdom is not of this World” by actually constituting a worldly kingdom, a kingdom for Christ Jesus on earth, which would be on the physical plane. The Roman pope gradually became the one to say: My Kingdom is the Kingdom of Christ; but this Kingdom of Christ is from this world; we have constituted it in such a way that this Kingdom of Christ is of this world. However a consciousness prevailed that Christ's kingdom was not one which could be based on the 13 ground rules of external natural existence. People were aware that when they looked out into nature, lit by the sun's morning redness and the sunset's glow, by the stars, then it is not only a matter of what the eyes saw, what the ears heard or the hands could grip, but in the widths of infinite space at the same time existed something of the spiritual kingdom. Everything visible in the world is to some extent the last outflow, the last wave of the spiritual world. This visible world is only complete when one is totally aware that it is the outflow of a spiritual world. The spiritual world is real; humanity has but lost their sight of this spiritual world. It is hidden yet it is a reality, an actuality. When a person enters the gate of death and is particularly blessed, he or she steps into the spiritual world. In times past people were far more lively in their thoughts than we can imagine. When the blessed ones who had died went through the gate of death, they entered a world which we can imagine in the very present time—permeated with clouds, permeated with stars, piercing the orbit of the planets. It was something so concrete that the souls of the dead could create the upper group depicted in the painting. The souls of the dead combined what existed for them out of the past to depict this concrete mystery, this concrete secret of the nature of the Trinity in their midst: as the Father God—out of the character of the present: the Christ Jesus—and out of the reality of the future: the Holy Ghost. In the reality of that present day world, if the physically sensed world did not appear as a mere illusion to people and let them live like animals, what differentiated itself in the reality of time had to appear on the physical plane in sighs, as a reference to the invisible spiritual world weaving and living above the clouds. Future generations have to have living signs for those not yet born and for those who are now passed over souls and are in possession of direct sight. On the altar stands the Chalice with the Sanktissimum, the host. This host or wafer is no mere bit of external matter for people who stand on the right, left and around it, but this host is surrounded by its aura. Within this aura of the host forces work which pour down from the Trinity. Such imaginations experienced by the heads of church fathers, bishops and popes regarding the sanctity of an altar are incomprehensible by present day humanity. This imagination has elapsed in the course of time. A moment is eternalized in this painting by the people below the altar rising: here is the mystery which is positioned on the altar: something surrounds the host. This something can be seen by those who have died, namely the blessed ones: David, Abraham, Adam, Moses, Peter and Paul—these departed ones look upon this in the same way we on the physical plane would observe things in the sense world. When we look at what is below, under the central sacred sacrament, we have to some measure an image in the lower layers of the painting of which a person like Pope Julius II said: This, in its great glory, I want to establish on earth in Rome if at all possible; such a kingdom, such an empire—not a state but an empire—in order for things to take place in this empire and be so enveloped by these auras that the past and its impulses live on in these auras. An empire that exists in this world but which, because it is of this world, contains signs and symbols for what lives in the spiritual world. Ideas of this kind Julius II incited first in Bramante and then in youthful Raphael. Thus it came about that the young Raphael could compose this painting. In a way Julius II wanted this painting in his study, have it constantly before him like a holy saying on which Rome had to be based because it contained the most important things in the mysteries. However this empire had to be on this earth, of this earth with a spiritual inclusion. If one allows all these experiences we have spoken about to work on one's soul, from its impression one might say: the spiritual world has been pushed back into the East since the 9th Century as is shown by the clouds driven backward and up, waiting for their time to come. In contrast there were preparations being made in the West for the 5th post-Atlantean epoch in which we are all still living and in which we will live for a long time, which exists under the signature: My kingdom is of this world and this kingdom will increasingly become more of this world. However this kingdom which is of this world was founded nearly from the beginning of the 5th post-Atlantean epoch under the influence of old people like Bramante and Julius II, but also the youth Raphael. The most important historical things happen subconsciously and from this subconscious yet wise basis Julius II called Raphael. We know that humanity was becoming ever younger through the centuries; we know that since the beginning of the 5th post-Atlantean epoch the age of the twenty eight had been reached and it was now “27 years old”. Certainly Bramante and Julius II were old people but they were not as directly placed in the world as could the youthful Raphael in his young body with youthful forces of twenty-eight when he painted this way. This is an important spiritual background in the development of humanity. We can recall how Raphael painted in the characterized thought (explained above) of Rome at the time; he painted to a certain extent in protest against the 5th post-Atlantean epoch for the fourth post-Atlantean epoch. This was not the case but let us hypothetically argue that it was thus in Raphael's soul: we can imagine that in his soul, in his subconscious soul lived knowledge which would be coming out of the 5th post Atlantean time. Out of this godless, spirit-robbed world of the 5th post-Atlantean time humanity's thoughts would be permeated with bare, barren and icy space where sun and spiritless planets depict the dreary space, spiritlessly imagining the world and try, according to spiritless laws of nature, construct the unfolding of the world. Let us imagine what had been presented to Raphael's soul: the reality of the spiritual emptiness of the 5th post-Atlantean epoch. Raphael's soul had counter acted: It should not be like this, I will throw myself against this mindless epoch with its imposed notions in frozen space with mindless mist in the form of the Kant-Laplace theories, with my lively spiritual existence. I want to permeate the imagination as much as possible in this dreary existence with true imagination which offers itself to clairvoyant understanding of the world.—Suppose this is what Raphael's soul depicted. Thus it appeared in his subconscious soul; it had even appeared in the same way in the soul of Julius II. Our age really doesn't need to despise great minds like Julius II or even the Borgias as is done with historical winners, because history still has to reduce some judgements regarding our contemporaries—the greatest ones of our times—just as it did with the Borgias or Julius II and will be the case of individuals in the future. People present at that time just did not have a distance to it. Raphael was born at the start of the 5th post-Atlantic epoch, one could say, as a child of the 5th post-Atlantic epoch. He was really born out of this 5th post-Atlantic epoch but as a lively protest against his age—he wanted to stand within its beauty which this epoch no longer experienced as real; this epoch strived to insert sensible spirituality into de-spiritualized certainty and impose that on the 5th post-Atlantean epoch, as has been discovered from spiritual research. Raphael's aim was more or less to depict clear images visible in the spiritual realm, imported from that realm into this world, in a painting filled with signs of the supersensible, thereby creating another world. As a result this image is through and through a true picture because it has originated in a lively experience arising from that time. Just consider this particular time when the child of the 5th post-Atlantic epoch drew the entire imaginative, spiritual imagery of the 4th post-Atlantean time into the 5th. Roughly at this time, during nearly the same year, a Nordic personality slipped up the penitent's stair in Rome, the stairs acclaimed for their ability to be equated to godly work according to the number of stairs climbed, because the number of steps taken on the stairs meant the same number of days relieved of hell fire. While Raphael was painting in the Vatican the Camera della Segnatura and similar images, this Nordic person, so devoted, in full of belief, so concerned for his soul's salvation, ascended the stair—so many stairs for so many days free from purgatory, doing work to please God. While he was thus climbing the stair, he had a vision—the vision showed him the futility of such holy work rushing up the stairs—a vision which ripped open the veil between him and that world which Raphael as a child of the 5th post-Atlantean time was painting as a testament of the 4th post-Atlantean time. You can recognise this person as Luther, the antitheses of Raphael. Raphael, even when he was looking around in the outer world, would see colour and form, all kinds of spiritual images, everything as expressions of the supersensible world yet reflected, expressed as sensual colour, forms and gestures. Luther was at the same time in Rome, filled with song and poetry, yet amorphous, formless in his soul, rejecting everything in this world which surrounded him in Rome. Like the spiritual world was pushed back in the 9th century into the East, it was now a testament of the 4th post-Atlantean epoch in Europe. Luther pushed it all back. Thus in the future the threefold world presented itself: in the East spirituality was pushed back, in the South it was somewhat divided as the testament of the 4th post-Atlantean epoch and again became pushed back and rejected. The musical element of the North took the place of the colour and form-rich testament of the South. Luther is really the antithesis of Raphael. Raphael is a child of the 5th post-Atlantean epoch, his soul however contained everything which lived in the 4th post-Atlantean time. Luther is a late-comer of the 4th post-Atlantean time, he doesn't belong in the 5th post-Atlantean epoch; one might say he was transferred from the 4th into the 5th. In his frame of mind Luther was completely within the 4th post-Atlantean time. His thoughts and feelings were like a person living in the 4th epoch but he was transferred into the 5th and lived now out of an echo sounding into the 5th epoch with its blatancy, its obvious natural history and ice fields of barren spirituality. Raphael had the soul content of the 4th post-Atlantean time; Luther, even though he was transferred out of the 4th into the 5th, had a soul standing right in the 4th post-Atlantean time but rejected everything external, he wanted by contrast to create everything which had nothing to do with external work and external human activities—a soul based solely between the formless inner connection of the human soul and the spiritual world, dependant on faith only. Just think for a moment how a painter like Raphael would have painted out of southern Catholicism, and compare how it could be painted from a Lutheran standpoint. What would he paint? He would paint a Christ figure somewhat like Albrecht Dürer's; or he would paint a religious person in whose physiognomic expression one would recognise a soul with nothing in common regarding the material surroundings and the objects within this environment into which it has been imposed. Thus one age connects to another. In the present time mankind has quite different ideas. This you see in paintings where Christ is depicted as a person amongst the people: “Come, Master Jesus, be our guest”—as human and equal as possible:  In our painting we have a group of Bishops, learned church fathers, and in the middle the obvious sign, the symbol. This points to the supersensible world; the Trinity is concretely included. Let us lift out this “Trinity” in particular. We have another painting which represents this Trinity on its own.   At the top we see the Father God, below that, Holy Ghost and the Son. You behold these members as concrete content of the future, the present, taken out of the past. It would not have been appropriate in the world view of that present time to mix the blessed souls of the dead directly with the observation of the outer visible world. However Raphael used, in the sense of the imagination of that time, what he observed as the truth, the free view in the widths of natural realms. To a certain extend he had to express the blatant obviousness that filled the space was not the truth; but the truth places them within the space. Thus we have at the bottom—you still notice the line of the horizon—the width, infinity within the expanding perspective. To a certain extent protest is expressed against representing nature at present as a purely sense perceptible image. Raphael didn't simply arrive at this image and hit upon the composition. In order for it to become clear, let us consider two of Raphael's preliminary sketches towards the painting's gradual development:  Imagine the entire story, from the time Raphael came to Rome roundabout the time Julius II called him to execute the commission in 1507, 1508, and try include this into the painting which he had in his imagination. Gradually he was first instructed by Julius II; gradually a relationship developed in him between space, nature and the supersensible and sensible aspects in the human group, how it had to be.  Section: the church teachers, in crayon (Windsor, Königliche Bibliothek) Also the other sketch refers more to the lower part than the first sketch, with still incomplete indications. You see it hasn't come into its own. What Raphael came to was this: he had to really imagine himself into that time and the relationship between the spiritual world and nature. In olden times, still up to the 9th Century, there was still a clear imagination of the relationship between the human past and the natural present. The people before the 9th Century—as grotesque as it may sound to mankind today—didn't think that when something was happening to them, it was by chance; no, they knew that when something happened to them it was because of the events into which they were being spun was where the dead were living, connected to them through karma. Before the 9th century the events which surrounded us place the dead before us. Such images diminished gradually and remained in the past as I have characterised for you in the 16th Century. Returning once more to the 9th Century we arrive at an imagination which needs consideration: a timely separation between the natural- and the spiritual world was not apparent for these ancient folk. Nature was at the same time a continuation—before the 9th Century, mind you—a continuation of the spiritual world. Already during the Greek times the human being had introduced their own I into their world view, by using thinking. Raphael was painting—he expressed this in the upper part of the canvas in the image later called “Disputa” even though certainly nothing was being disputed—and introduced a female figure out of the symbolism of that time with the motto: DIVINARUM RERUM NOTITIA = divinely written comment. Basically before the 9th Century the world view included the “divinely written comment” and nature was like a wave of the godlike world extending below to where mankind found itself.   This entire notion, as I've mentioned, was pushed back to the East and the echo remained within the imagination, like a testament painted by Raphael from the 4th post-Atlantic epoch. In those days it was deliberated from the south to establish the kingdom of Christ on the physical plane itself as a real empire of power. Pope Julius II had even, like other similar personalities, written on his flag what he really wanted. He wanted to really establish this which could not happen because Luther came along, as did Calvin and Zwingli. He wanted to create the foundation for Christ's Empire in this world. He dared not say so. One can usually see this in such personalities as something esoteric. Julius II did not dare go through Italy as a commander in order to harness the Italians to his empire. He said it differently. He said he was going through Italy as a commander in order to free the Italian folk. This is what was said. In later times it was said something or other should be done to free the folk while this only hid the real goal. At the time however, many believed Julius II went through Italy to free the separate Italian nations. It didn't occur to him, just as little as it occurred or could in anyway occur to Woodrow Wilson, to set some or other folk free. Now, you see, here we have this immense border, one might say, between the two time periods: the backward push to everything southerly. Retained from this is the division in the world view in the Greek time. It was clearly as follows: What had streamed through nature as deeds of the dead was no longer present when people developed spiritual powers in themselves, unfolding it in their souls; it then doesn't become DIVINARUM RERUM NOTITIA, not something “written up as godly things” but becomes CAUSARUM COGNITIO—and attains “direct knowledge of causes in the world”. Here care should be taken not to want an interpretation of nature in its totality as an outcome. To come to an idea of nature—this Julius II felt compelled to shout in thunderous words—an imagination was to be made to show that the sun rises, the morning- and evening glow exists as do the stars, and just as people did in the 5th post-Atlantean epoch, it meant lying. In fact one denied that the souls of the dead were within the Trinity which was really something capable of imaginative expression by looking back to the dead souls, David, Abraham, Paul, Peter and express the Holy Trinity. Julius said: Leave away nature and the old Eons, only depict the youngest Eons! Do you want to rely on yourselves? If you want to develop through only human forces, depend only on what is inherent in the physical body, then you arrive at an external science regarding the outer nature of people, a science only in so far as the human being has no connection with the endless expanse of the world, but is hemmed in, interwoven within the boundaries it sets itself. This is roughly what Julius II told Raphael: If you want to paint what the human being through his own soul faculties know about humanity then you must not paint the people out of an endless perspective in nature, but include the people, whether genial or wise, in their self-made borders. You must include them in halls to show: from these rooms where the world is governed—because Julius wanted to have the world depicted as it would have become had no Luther arrived, nor a Zwingli, or any Calvinist.—If you want to paint the world as it is governed from these rooms, then paint on the one side the reality existing in the breadth of nature and on the other side, what people can find if they only sought forces from within their own souls. Then you may not paint nature but paint the people in their self-imposed borders. This is what we have when we allow the contrasting aspects in the image to work on us ... the so-called “School of Athens”.  This painting, later becoming known as the “School of Athens”, was often painted over in the course of time and so the man standing in the middle had his book painted over with “Ethics” then later with “Time”—that was painted even later. The painting is in many ways ruined and one can't find the true image of the original painting today in Rome. In Raphael's time it was never called “The School of Athens”, this only happened later and then theories developed about it. We can imagine it essentially thus: truly the world is measured through the changed painting (197) when we peer into the endless realms of space and imagine nature not with obvious senses but permeated with everything existing in eternity and temporality, permeated with that which has gone through the gate of death. Taking knowledge from within one's own soul and representing it in everything coming together, like these wise men, here (202); the heavenly knowledge which can only be found built up within oneself, is represented in a personality which points upwards (203). No inartistic stupidity is needed to see Plato in this figure. (See below) You can imagine the following: the gesture of the rising hand represents the word being spoken by the figure on the right. The personality on the right begins to speak as if his expression is translated into words. Everything originating by itself in the human soul can only be truly imagined if it is contained within an enclosed space, where one remains within oneself. If one searches within for an image of nature then nothing other than an abstract image of nature will be found, much like the Copernican world view represents which is not a picture of concrete nature. Thus Raphael took the task from Julius II and placed it before the godly experience which could live by itself in the human soul in the beginning of the 5th post-Atlantic epoch. Here everything of worldly science is grouped, but worldly science raised up to divine concepts, to intellectual understanding of the godly. On analysis the seven free arts appear: grammar, rhetoric, dialectic, geometry, arithmetic, astronomy and music. Up to the culminating expression you can find the whole of worldly science applied to the divine and how this is expressed by the human word—here the opposites of looking and speaking are alive—expressed in the image itself. Un-artistic, amateurishly learned chitchat saw the entire Greek philosophy in the same image. That is unnecessary and has no relevance to the artwork we have been speaking about and of which we finally want to point out: it shows us how this painting, in the sense of that time, represents a true human experience—an experience which the soul discovers when it is allowed to find wisdom within itself regarding mankind. We have more details of this painting which I want to show you:   If you allow yourself to be drawn in more you will recognise the right sided figures are linked to the central main figure who is entering into speech; here on the right (205) we have everything which depends more on Inspiration, and to the left, (204) it touches more on Imagination and its equivalent. We have one more image of the central figures:  The opposite of looking and speaking is presented. Let us be clear about it—the present time can only be understood if we try to throw more and more of such glances into the past which we can do by experiencing such paintings in an artistic sense. Our time is the time in which something returns to itself. In our time there is a return in Europe—Central Europe, Northern Europe and in certain moods in Western Europe—of karmic connections with the European development of the 9th Century. This hasn't become particularly observable to most people, actually in fact, not at all. What happens today takes place out of necessity, the opposite manner used to spiritually grasp what Europe's destiny had to be in the 9th century. What had been pushed back to the East at that time was the spiritual world, so now it has once again to be manifested on the physical plane. The moods of the 9th Century after Christ are now reappearing in western European, in Central and Northern Europe. Out of Europe's east will develop something like moods out of the terrible chaos, spreading out in something like moods which will mysteriously remind us of the 16th Century. Only out of the combined harmonising of the 9th and 16th Centuries will mysteries originate which to some extent can give a degree of clarity for present day humanity who wants to rise to its own understanding of evolution. It is remarkable to see how in the 16th Century everything most secret and mysterious in nature, man and God, was visibly represented outwardly in art. The holy secret of the Trinity we have found in the most meaningful images of the world set before our souls. The opposite appears at the same time—the Protestant-Evangelistic mood which totally denies these holy secrets being able to share this historic period. At intervals Herman Grimm, a truly northern Lutheran spirit, speaks about the thoughts his contemporaries have regarding Christ, thoughts they treasure as wholly good within their souls—the exact opposite in Raphael's mood when he painted the world. You see, at the beginning of the 16th Century the Reformation brought evolution further which became the world's lot, even in Rome, in the sphere of Julius II, of the popes. But how? It became the lot of the world that people wanted to reflect about the supersensible worlds as if they were visible but visible through human development. As a result—this Herman Grimm discovered rightly—the Pauline Christianity became a particular problem for Raphael and his contemporaries—yes, even the figure of Paul himself. It can be said that up to the 16th Century Christianity was far more permeated by what one could call the Peter Christianity—Peter who saw the supersensible and sensible worlds as undivided, experiencing in the sensible world the supersensible within it, finding the supersensible in the sense perceptions. The extrasensory world disappeared from it. People were aware of this right up to the 16th Century. The experience of the Damascus secret living in Paul as a seer, and the figure of Paul himself, became a problem. As a result Raphael tried in his later development to depict, and include, Paul's figure in various paintings. It can be said: from the south a Reformation wanted to be established with the aim to depict the Pauline vision in the world in such a way as I set before you now, as it lived in Raphael's paintings which originated through the inspiration of Julius II. Paul was a problem for him. You appreciate this when you research Paul's form in Raphael's other paintings. You see a visual expression of the music of the spheres in the “Saint Cecile”.  Naturally it is inaccurately expressed. Left, in the corner, is the practical shape of Paul. Raphael made a study of Paul in a painterly way. Repeatedly Paul posed a problem. Why?—Because Paul's quest originates from within him as a human individuality through which he strives to have sight, penetrate into the sight. Here we see it in his whole attitude, in his gesture: Paul as he participates in something self-evident to others as a seeker. He develops both sides, therefore if it comes down to him, he shows Christian revelation differently. As Paul understands—you see it here, how Paul teaches—it became a problem for Raphael. Now we have another painting: Paul speaking in Athens.  You can see Raphael studied Paul. What did Paul become for him?—The hero, the spiritual hero of the Reformation who should have succeeded from the south, but did not succeed. This impulse was pushed back and later Jesuitism from the South was put in the place of the Reformation—more about that at another time. Paul should have established the Kingdom of Christ on earth as foreseen by Julius II. Now characterise for yourself the two Paul heads, which we have before us now and allow it to really work on us.  These are heads studied by Raphael in which he wanted to depict through the physiognomy a gaze penetrating the secrets of the spiritual Christian world, into the spiritual secrets enabling words to outwardly pronounce these secrets; we have in Paul the binding link between the world of causes and the world into which only those with blessed vision have access, the supersensible world. Paul is looking and teaching, the connecting link between the world of the 5th post-Atlantean epoch and the ancient spiritual time. Remind yourselves of your consideration of the Paul physiognomy, the Pauline gestures right up to the movement of the fingers—here only the arm is lifted—and be reminded of that ...  ... consider these and then look once more at the figure in the so-called “School of Athens”:  ... and compare that to the two heads of Paul which we have looked at (235, 236) with the heads here (203) on your right and you have such a personality in whom seeing has become words, one might say: because Paul, who grew out of seeing the results of the Mystery of Damascus and became the orator of Christianity, made his pact of compromise with what can be found in the Causarum Cognitio when the experience of the physical causal world is elevated into a relation of possible experiences of divine things. As a result you will experience something like the constant “Signatur” which wafts through the “Camera della Segnatura” when you look over the image which later was called the “Disputa”, to what is called the “School of Athens”. In the “Disputa” is the truth, the spiritual truth in a nature filled space; glancing over to the other, opposite wall, so companions and visionaries encounter Paul the teacher who points to the worldly learning from which everything can arise which the human soul can find within itself. Looking at the fresco, which is the so-called “School of Athens”:  ...so one finds a soul living in the central figure with a content which is painted in the opposite fresco:  ... then one roughly has the connection. Take the one wall—everything that is within the soul, all one does not see except as the outer bodily aspect, that very aspect is revealed on the opposite wall, on the fresco of the so-called “Disputa”. I would like to say: if you could see into the souls of these two people painted on the one wall, then you will see what lives in the souls of these two people on the opposite wall, on the fresco. More about this later. |

| 292. The History of Art II: Fourth and Fifth Post-Atlantean Epochs, Medieval Art in the Middle, West, and South of Europe

15 Oct 1917, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Particularly in our present time it is imperative to totally understand the current 5th post-Atlantean epoch in which we stand, with all its peculiarities, in order for us to become ever more and more conscious of how affective we are within it. |

| The papacy in the time from the 9th century, before the middle of the 9th century where the ruling of Europe was so vigorously taken under control, where all relationships effectively extended, must not be imagined as the same effective papacy in a later century or even today. |

| This is what we find towards the conclusion of every time period, towards which Rome out of such a deep understanding through the three to four centuries created in the European realm, which wanted to rise out of folklore. |

| 292. The History of Art II: Fourth and Fifth Post-Atlantean Epochs, Medieval Art in the Middle, West, and South of Europe

15 Oct 1917, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

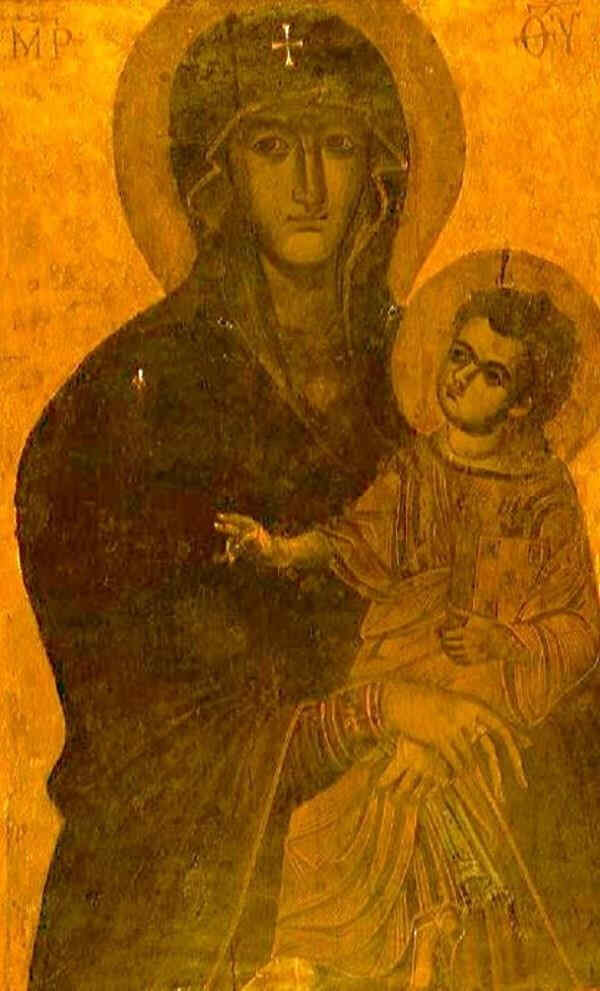

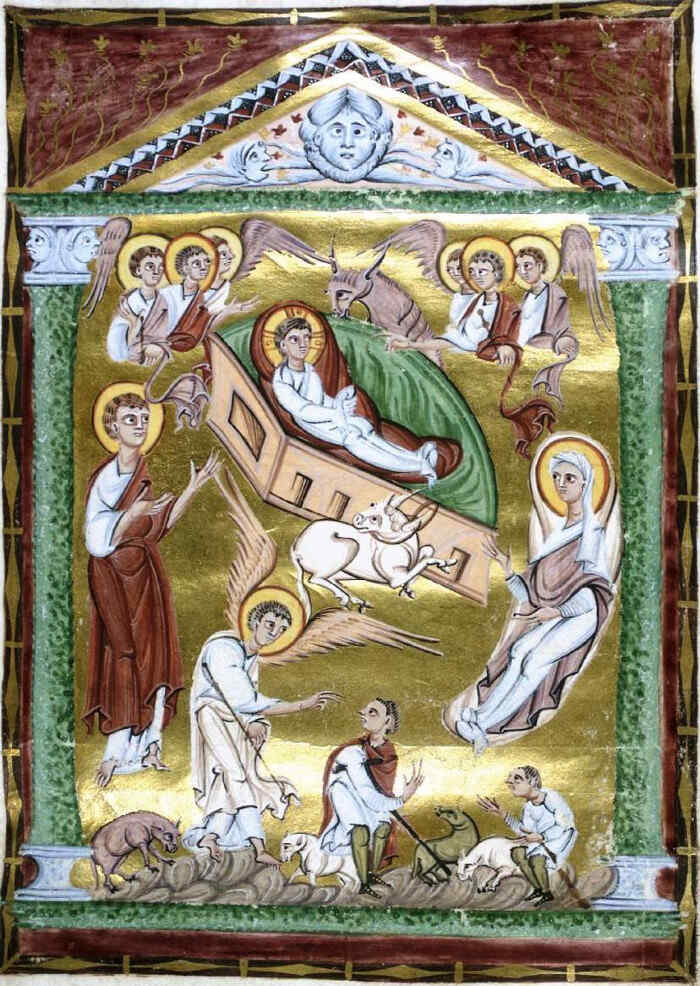

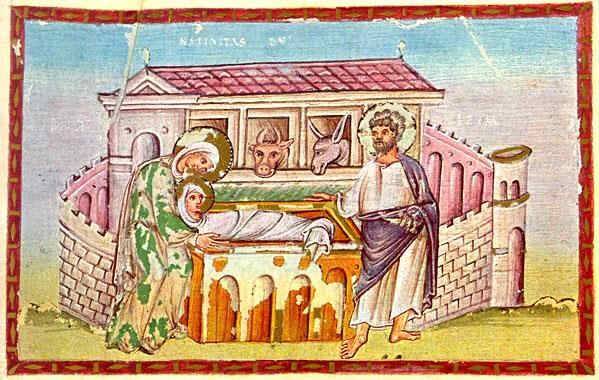

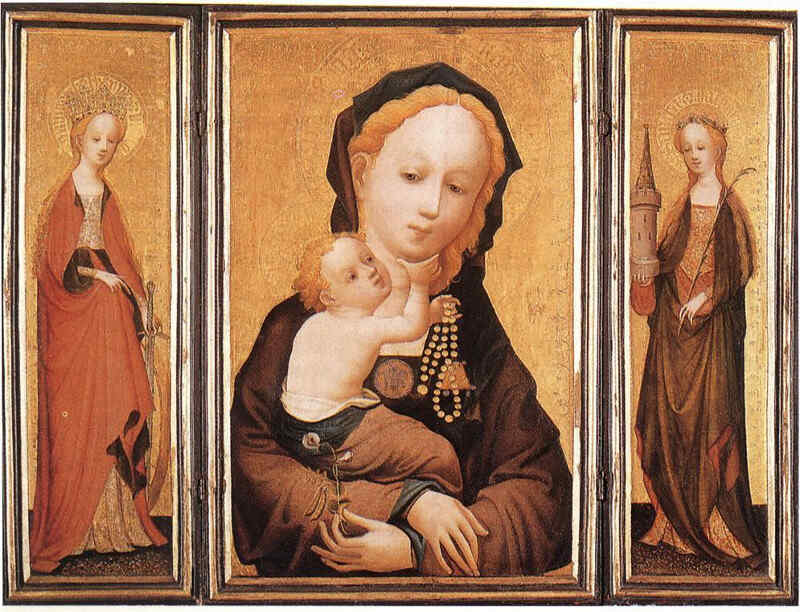

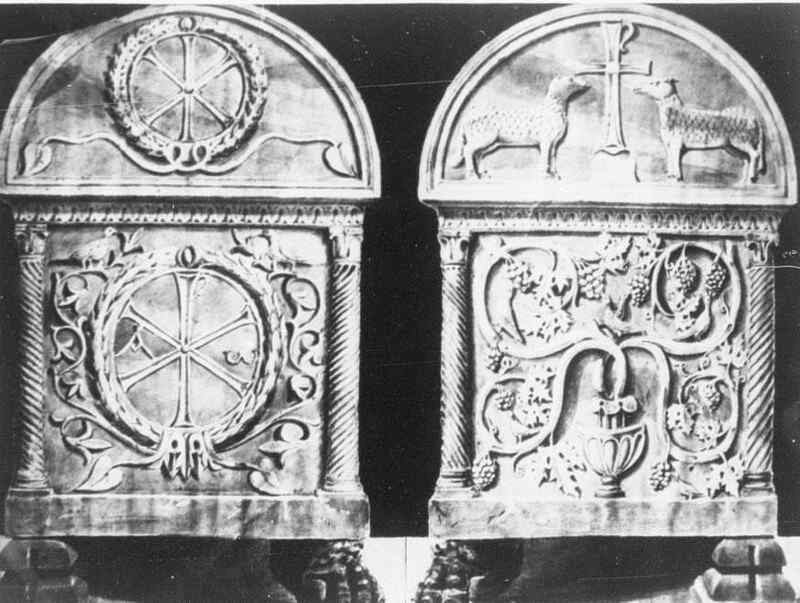

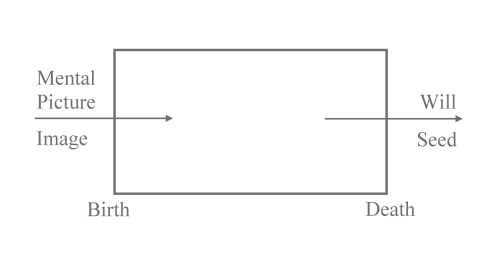

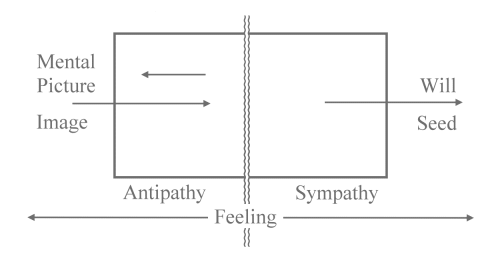

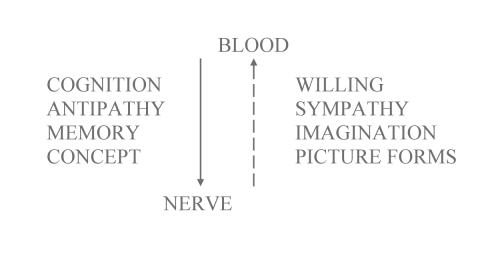

I think that it is good right now to become familiar with the most varied areas of life and the laws of existence which I have been referring to during these lectures. I want to say these laws of existence take on an importance in their realm of the spiritual life, an importance of being, which up to now has frequently not been taken into account in world opinion. Particularly in our present time it is imperative to totally understand the current 5th post-Atlantean epoch in which we stand, with all its peculiarities, in order for us to become ever more and more conscious of how affective we are within it. You know of course that we consider the beginning of the 5th post-Atlantean epoch beginning at the start of the 15th Century, from about 1413 onward. The beginning of the 15th Century was a significant, profound, incisive point for western humanity. The creation of such an about-turn which came about didn't happen all at once, it was preparatory. In the first moments of this epoch one only sees a gradual expansion. Old patterns from the earlier epochs transform into the new one and so on. Preparations were being made for a long time which were only really being experienced as a mighty reversal at the start of the 15th Century. If we want to consider another strong western historical impact in the centre of the Middle Ages, we may look at the rule of Charlemagne from 768 to 814. If you wish to visualize everything which happened in the West to the furthest boundaries up to the time of Charlemagne, you will have difficulties with this self-visualization. For many observers of history today such difficulties do not exist because they all shear it under the same comb. Only for those who want to look at reality, will such deep differences exist. It becomes quite difficult for people in today's world of experiences and impressions to reach a concept about the completely different condition of life in Europe up to the time of Charlemagne and beyond. We may however say that after Charlemagne, in the 10th, 11th and 12th Centuries a time began in preparation of our own epoch, the 5th post-Atlantean epoch. Up to the time of Charlemagne old relationships actually flowed which in our present day, as we have already said, we can't have a true imagination. Then again preparations were beginning for a new epoch, and in these three centuries, the 10th, 11th and 12th—it started in the 9th already—events took place in Europe in all areas of life producing forces which were expressed later, particularly in the 15th century. One can say these centuries just mentioned was a time for preparation but people today are hardly inclined to refer to this just as little as they will say Rome is in control of European affairs. The papacy in the time from the 9th century, before the middle of the 9th century where the ruling of Europe was so vigorously taken under control, where all relationships effectively extended, must not be imagined as the same effective papacy in a later century or even today. It can rather be said that in those times the papacy knew instinctively what the most important areas of life needed, in west, central or southern Europe. I already pointed out last time that the oriental culture was gradually pushed back; it had to wait in eastern Europe, in Byzantianism, in Russianness. There it waited indeed, waited right up to our present time. General observations can develop particular clarity in those areas which, in the broadest sense, one can refer to as artistic. If you want an idea about what had been pushed back at the time to the East, what the west, central and southern Europe should not acquire, if you want to reach an understanding about it, then compare it with a Russian icon:   In the picture of the Virgin Mary of the East is an echo of what had been pushed back into the East at the time. In such a picture quite another spirit holds sway than can ever be found reigning in western, southern and central art; it is something quite different. Such an icon picture still today presents an image which has been born directly out of the spiritual world. If you imagine it in a lively manner you can't imagine a physical space behind the Russian Madonna image. You can imagine that behind the picture is the spiritual world and out of the spiritual world this image has appeared: just so are the lines, so is everything in it. When you take the basic character of this image as it is born out of the spiritual world then you have exactly that which had been held at a distance in the 9th Century from western, southern and central Europe:   Why? Such things should be thoroughly and objectively considered historically. Why did this have to be held back? Simply on the grounds that the nations of Europe—central, western and southern Europe—had completely different soul impulses which were not in the position to understand humanity out of original elementary nature, this was being pushed back, stopped in the East. The nature of the western European soul was quite differently focussed. When this which was being pushed back to the East was transplanted into central, western and southern Europe, it could only remain external, outside the east of Europe; it could never grow together with the central, western or southern European soul distinctions. An area had to be created in western, southern and central Europe, an area for what gradually wanted to come out of the depths of the very folk soul itself. I would like to say Rome, in actual fact, understood this with genial instinct. With disputes regarding dogmatism showing quite a different character, the content of dogma disputes is not the real story; the content of these disputes is merely the final spiritual expression. It goes much further. Among other things it was about what I have just been characterising for you. So we see that from the 9th Century and into the next centuries Rome worked ever more strongly for a space in Europe where the real striving of the folk souls could unfold. The striving of the folk souls also appeared in greater clarity. You see, when you focus on what could have been brought to the fore if the eastern influence had not been pushed back but could stretch over Europe—Charlemagne made a large contribution - if it had stretched over Europe then Europe, as I've already mentioned, would have made available certain observations of representations which speak directly out of the spiritual world. This did not happen, firstly because Europe had to prepare itself for the materialistic 5th post-Atlantean period which was prepared most intensely in central Europe. Interest centred mainly on everything other than what came directly out of the spiritual world like line, form and colouring. Humanity was interested in something different. Above all there was an interest in Europe for contemporary events, for reporting and for results. By studying individuals, singled out in humanity, you realize they have positioned themselves in the course of historic, relatable events. The 10th, 11th, 12th Centuries can also be called the Germanic Roman Empire because from Rome the capacity was created, a capacity which spread for an interest in relating stories, an interest in the working of time and for conceptualising a particular form set in time. You see, this is again a different viewpoint from the viewpoint I indicated in similar lectures in previous years. This cooperation of the central European empire with the Roman church and its spread is an inner image of the way the 5th post-Atlantic epoch prepared central Europe at the time. From this it is clear that central Europe prepared itself in this period with very little interest for spatial educational art. Constituted informative art became borrowed - just remember the presentation which I gave you in previous years—borrowed from what came over from the East, spread, one might say, through to the very joints of principal interest. What shot up out of the folklore itself was being told. The content which was to be told had to be taken out of national character, intimately connected with nationality. You can encounter amazing images of central European life, life in the areas of the Rhine, the Donau and the northern coastline in the depiction of the songs of the Nibelungen, the Walthari and `Gudrun'. The manner and way in which these writings are presented indicate their obvious interest in events of the time. Look how in the time of Charles the Great when the poem `Heiland' originated, the stories of the Gospels are woven into the poem with central European characters, characters extracted from biblical events and placed directly into the central European interests of the `Heiland'. It had to be born out of the life of the European folk soul. Through this the eastern tradition, which cares little for the temporal and historical, was pushed back. For this reason, it was pushed back. If we observe how these concerns of the European nations rise from deep underground and reach the surface, then it is often only possible, and with difficulty, to really penetrate into the depth of feeling, into the deep soul experience which the European human spirit connected to in its own deepening encounter with the essential spiritual events. One might say, that which was pushed back to the East from spatial infinity and its manifestation out of space, which had to appear superficially in central Europe should reappear directly out of the human souls themselves, out of the depths of the soul, not out of the widths of space—but out of the depth of souls. The mysterious prevailing of soul depths under the surface of direct observation was already something living at that time in human souls. During the centuries we've been talking about, people were instinctively permeated with the knowledge that their souls had in the depths of their being secret impulses, appearing only sometimes at celebratory moments in their soul experiences. Life seemed deeper than what the eyes could see, the ears could hear and so on; something unfathomable rose from soul depths as a profound experience. I could say we experience an echo of this kind of thing when we hear something as beautiful as the poetry of Walthers von der Vogelweide, who to some extend created an ending to a purely linguistic age, an age when the ability to depict formless manifestations in soul depths in a pictorial manner had not yet developed. In these soul depths we are stirred when we allow Walthers von der Vogelweide's small poem to work on us, where he speaks about his own life in retrospect. Maturing as a man when knowledge grew in his soul and light fell on his soul depths from which knowledge had previously appeared as mysterious waves in a dream, now appeared in a mood, he expressed as follows: