| 80c. Anthroposophical Spiritual Science and the Big Questions of Contemporary Civilization: Supernatural Knowledge and Contemporary Science

06 Nov 1922, Delft Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Is our morality just a vapor that rises in the purely natural world order, which, according to a modified Kant-Laplacean world creation, transitions to the more complicated, more perfect being, only to sink into heat death, whereby the end of that which arises in us as moral impulses would be given with the general cosmic cemetery? |

| 80c. Anthroposophical Spiritual Science and the Big Questions of Contemporary Civilization: Supernatural Knowledge and Contemporary Science

06 Nov 1922, Delft Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

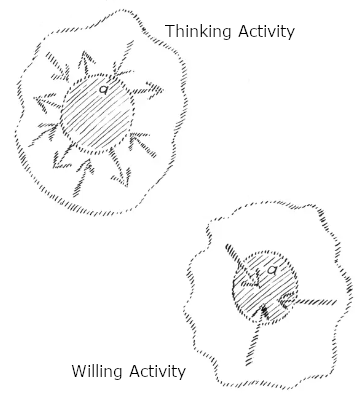

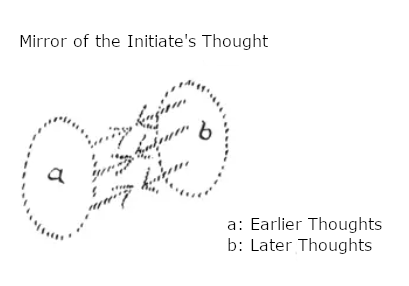

Dear attendees! First of all, I would like to express my heartfelt thanks for the kind words of welcome and for your invitation to this lecture. I have taken the liberty of making the relationship between the direction I represent in supersensible knowledge and the science of the present the subject of today's presentation. The objections that are raised against the possibility of supersensory knowledge in general – and in particular against the direction of supersensory knowledge that I intend to present and that works towards scientific methodology – are based primarily on the opinion that supersensory knowledge contradicts the scientific method of research and the actual task of scientific thinking. Now I would like to point out one thing, first of all historically. I would like to point out that such extrasensory knowledge, as it is sought through anthroposophy, can actually only be a result of our time, of our civilization, and for the reason that this our time — and by that I mean roughly the last three to four centuries up to the present —, because this our time has only produced what can be called a complete way of knowing the world of the senses. Sensory knowledge as we have it today, as a result of scientific research methods, was not available at all until three or four centuries ago. This sensual knowledge is actually only a result of the endeavors that were initiated by Copernicus, Kepler and others, and they celebrated their greatest triumphs in the course of the nineteenth century, particularly in its last third, and also in the twentieth century. Any kind of world view, any kind of spiritual research that wanted to develop in contradiction to this scientific knowledge and way of thinking today would certainly have no prospect of having any kind of convincing effect on those people who count today, on people with a scientific education. Out of this conviction, anthroposophical spiritual science, above all, seeks to work in such a way that it becomes aware: It has to work in this scientific age of ours. Not only does it not want to contradict science, it wants to work entirely from the same foundations, the same prerequisites as recognized science. But, precisely because we have come so far within the methods of sensory observation and experimentation, because we have developed exact types of knowledge within these research methods , and because these exact methods of knowledge are directed primarily towards the investigation of the sense world, we need – and I believe I can explain this to you today – we need a knowledge of the supersensible today. Science itself demands that the unbiased gain knowledge of the supersensible. For let us just visualize for a moment, my dear audience, how knowledge was gained in earlier centuries, or even further back. People were unable to observe that which expresses itself according to its own laws in the external sense world. One need only recall how difficult it was in the course of the nineteenth century to expel from science the so-called life force, a mystical monster that had been created purely through inner speculation, through inner thinking, this life force that was not a result of observation or experimentation, that was purely imagined. In a way, it was the last remnant of the old mystical monstrosities. Before the actual scientific age, people believed that they had to put as much into their sensory observations through self-opinionated thinking as their external sensory observations gave them. Usually, one does not notice – and it is not necessary for ordinary science – how, let us say, a scientific book looked in the twelfth or thirteenth century. There is just as much in it that a kind of scientific fantasy has put into things from the human being, from what has been inspired in the human being by his emotions, his feelings and so on and so forth, as from external observation. What observation and experiment can scientifically give to people is provided by the empirical sensory sciences in connection with mathematics. But what this science has become for the education of educated humanity in modern times is what, above all, something like the anthroposophical spiritual science meant here must focus on. For not only have we explored outer nature and man himself, insofar as he is an outer nature, through observation and experiment; not only have we thereby obtained a sum of results that confront us today in the practical application, in the technical practical application of modern natural science, that confront us in natural science, and so on and so forth; not only has humanity gained from this development of natural science, but above all, humanity has undergone a tremendous education through this laborious work, in which man forbids himself to transfer anything of his inner thoughts and dreams into natural objects and natural processes , man has managed to use his thinking only to shape his observation and his experiment in a pure way, so that observation and experiment express their essence and, for this external science, thinking is basically only the servant of that which is to be produced in external science, so that it expresses its lawfulness. To achieve this, a significant renunciation was necessary in relation to what had previously been incorporated from the human soul into the world view. A moral development is already taking place alongside scientific development and its results, which has brought humanity to the has brought humanity to the point where man renounces seeing anything spiritual in natural objects and natural processes, and applies his own spirit only to the fact that nature expresses itself purely and in accordance with its essence. This was not known in earlier centuries, before about the fifteenth century, to make thinking only a servant of the method, so to speak, so that nature can express itself. What has been achieved in inner human development, what one can go through inwardly in the soul through the scientific method, that is what anthroposophical spiritual science, above all, wants to acquire. In other words, my dear attendees, anthroposophical spiritual science does not want to conquer any terrain that the other sciences have; anthroposophical spiritual science wants to penetrate into the world of the spiritual from the same attitude that is otherwise used for research today. We need only consider what has brought about our scientific progress; it has been brought about precisely by the fact that man has completely excluded himself, that he, by letting nature speak, does not add anything of himself to his knowledge. But as a result of this, it turns out in the end – people usually do not believe it, but it turns out – that because man does not allow his will, his creative imagination, to flow into nature, because he makes thought only a servant of his research, it turns out that he can get to know everything in the world that is not himself. By excluding everything that lies within him from the justified objective method of research, man learns to recognize everything except himself. He is ultimately excluded from all that constitutes the very greatness, the triumphs of modern knowledge. Thought has become, so to speak, only a language about natural processes. And in fact, in today's external science, we only apply the mathematical to our full satisfaction in internal experience. But with this mathematical, one stands in a peculiar way to nature, if one does not simply apply it naively, but if one consciously asks oneself: What are you actually doing when you apply mathematics to nature? If one draws the mathematical externally, it is only a drawing. In reality, the mathematical arises entirely from the human being itself. We build something purely spiritual in mathematics, and we actually only find that mathematics has this great justification in nature because we see how we can apply it, because it can be applied, so to speak, everywhere to that which we can observe and which we can experiment with. And we feel secure in mathematics because we extract this mathematics entirely from within ourselves. When we have a mathematical problem, it does not depend on whether hundreds of people say yes to it. If I understand the matter all by myself, I am secure. I live with my insight; I am completely immersed in it with my soul. And by grasping nature mathematically, by connecting what I develop within myself with natural processes in calculating experimentation and observation, I know that I am proceeding scientifically. I combine what lies within me, but what lies objectively within me, over which my subjectivity has just as little influence as it has over natural processes themselves. I combine the mathematical knowledge gained from within myself with natural processes. That, dear attendees, is basically the model for what is meant here as supersensible knowledge, except that one does not proceed exactly with external nature, but first proceeds exactly with oneself. One starts from what I would call intellectual modesty. You say to yourself: You were once a small child with dreamy soul abilities. You developed into what you have now become. The abilities through which you can orient yourself in the world have gradually arisen in you. Now you say to yourself: Just as you have developed through life and education from the abilities of a small child to those that you possess today, can you not go further? Could there not also be abilities slumbering in the soul of the adult human being, just as they slumber in the child? And could one not take one's self-education into one's own hands, so that one can go beyond the abilities that we are so proud of in ordinary life, just as one goes beyond those that one had as a child? But now, people say, scientific education in recent times demands that one does not fumble around in the vague nebulae, the mystical, by extracting human abilities from the soul. We have become accustomed to proceeding exactly in the mathematical-exact treatment of external natural processes, to proceed in such a way that one does not speculate dreamy-mystically, nor, as one says, merely immerse oneself dreamy-mystically, but rather to proceed in such a way that one follows each individual step with full deliberation, with full consciousness, as is the case with a mathematical problem. In this way one can develop one's own soul by awakening its dormant abilities. But the method of doing this is an exact one. One only develops into another soul being insofar as one makes every step one takes to develop these abilities as exact and supernaturally deliberate as one has learned in mathematics. Please note, my dear audience, that we take as our model what we do with the external world, whereby we do science from the external world, become scientists, and we develop the exact way we have learned to develop our own soul. So while today's science, the science of the present, proceeds exactly in its treatment of the external world, leaving it at the abilities that one acquires through ordinary life and ordinary education, and then proceeding exactly in the external world, one proceeds exactly in one's own development, that is, only those soul abilities that can be directly grasped need to be developed. One develops exactly. But this leads one to practise what I have characterized in my book, “How to Know Higher Worlds”, or in my “Occult Science”, or in other books, as the meditation and concentration in thinking appropriate to modern education. This includes what is necessary to develop inwardly in the manner indicated, and it encompasses many details. And anyone who believes that the anthroposophical spiritual science referred to here is a casual product of inner experience or fantasy is greatly mistaken. What is striven for in it is truly no easier to attain than what is striven for in any other science; it is only more intimately connected with the deepest longings and needs of the human soul, and concerns not only those who have to pursue botany, astronomy and so on, but concerns every human being as a human being. You can find more details in the books mentioned. I will only hint at the principles here. What is at issue is this: in modern, exact thinking, one has become accustomed to maintaining this structure of thinking while abstracting from all sense impressions. But one tries to bring the thinking that one has acquired into such activity and energization that, even if one has no external impressions, one can rest in ideas that one brings to the center of one's consciousness. It does not matter to what extent these ideas initially correspond to external reality, but it does matter that we do something similar with these ideas in our soul as we do, for example, externally and physically with our arm when we work with it or when we exercise it. We strengthen its muscles. Meditation and concentration are concerned only with the exercise of the soul powers. But by strengthening one's soul abilities in thoughts that one freely holds, without passively leaning on an external sensory perception, purely actively internally in thoughts, and by systematizing one's inner life, but proceeding with full deliberation in this one's own inner development and activity , as otherwise only the mathematician does, one finally comes to it - for some it takes months, depending on their abilities, for others it takes years, but everyone can basically achieve it according to the current stage of development of humanity - one comes to develop what can be called with some justification exact clairvoyance, exact clairvoyance. However much the word clairvoyance is frowned upon today, I use it ruthlessly because it has a certain justification. It has its justification for the following reason: Let us reflect on how and why we, when we are in the outer world of the senses, perceive the things around us as seeing human beings. We perceive them when the sun or another light source sends its rays to the things and these things become visible to us under the influence of an external light source. We as human beings are thus within the light-space that is there through an external light source. By continuing such exercises, which consist of meditation and concentration, as I have indicated in principle, more and more, we ultimately arrive at an inner experience in the soul that is not the same as the external light, but which makes us our own source of soul light. We really experience something, my dear attendees, which I would like to call an inner sunrise, a sunrise that has arisen because, through meditation, forces and abilities within us have been uncovered that previously and we are now able to really illuminate our environment with the soul light that we have kindled, just as the sun previously illuminated things in physical space. The awakening of an inner light justifies speaking of clairvoyance. And because we do not allow ourselves to bring about this clairvoyance in any other way than through exercises that are as straightforward as only the most exact mathematical and scientific problems, that is why this clairvoyance may be called exact. But as a result of this, my dear attendees, we also develop something more and more within ourselves that is otherwise only presented under the influence of external perception. Try to honestly admit to yourself what a tremendous difference there is between the aliveness in which we are with our whole soul, with our whole human being, while we perceive colors, while we hear sounds, while we expose ourselves to impressions of warmth; try to realize quite clearly how we we live completely as human beings in our soul while we perceive colors, sounds, and differences in warmth, and how gray, how abstract, how lifeless our ordinary thoughts are through which we inwardly envision the external sensory world, how pale these thoughts are. These pale thoughts, these inanimate abstractions, are inwardly filled with such liveliness through the exercises I have described that what most people run from because it gives them no warmth of soul, the abstract thoughts, becomes so full of life inwardly, so pictorially concrete, as otherwise only the impressions of the external sense world. This is, so to speak, the first step we have to take in exact clairvoyance: that we, by merely thinking, but having a strengthened, inwardly animated thinking, an energized thinking, that we, without receiving external impressions, are so as we are when asleep, that we thereby develop an inwardly active life in an activity that is otherwise just a thinking one, which is now completely illuminated and energized with real images, but with images that are not stimulated from outside, that arise from the human being itself. Now, however, we must continue this composure, for the sake of which I was able to call the acquisition of such a level of knowledge 'exact clairvoyance'; we must continue this composure to the extent that we feel completely subjective in this inner glow and image-generating. In the moment when we do not know that the whole tableau of images, the whole world of pictures that we produce as an inwardly self-illuminating one, is only our own being, is a world unto itself, in that moment we are not spiritual researchers; in the moment when we already consider this world of images to be real, we are visionaries, we are perhaps pathological personalities. A healthy continuation of sensory knowledge into the supersensible world requires that we also bring our composure to the point that I have just described, and know that what we have gained have attained is indeed more inwardly alive, saturated, and concrete than the wonderful structures — I call them that because one can indeed be enthusiastic about mathematics — than the mathematical structures are. They are our product, like the mathematical figures. But still, to be immersed in it with your whole soul, to experience it, while always having your full, level-headed self standing by, with both feet in the real world of the senses, that must be there, otherwise you are not dealing with exact clairvoyance, but with an unreal, fantastic being. By finding our way into this world of images, we can compare it to mathematical formation. But it is different. In mathematics, we know that we cannot apply it to our soul itself; we produce it from the soul, but we have to apply it to the external world. The external world gives us the content for it. The triangle as such is not a reality. But when I find the lawfulness of the triangle in an external sensual content, I penetrate reality in a certain way. But what one experiences in the way described as an inner world of images, as a result of meditation, in that one nevertheless senses an inner reality. You have to be clear about it as a level-headed person: it is only subjective, but it is an inner reality, it is not just a mathematical one, it is an inner reality. And if you go through this inner reality, you feel it out in your soul, so to speak, you devote more and more inner energy to experiencing inwardly what is contained in the images, then these images take on a very specific form for each person. We do not then live in remembered images, but we do live in a tableau that presents us with the formative forces of our own human beingness since our birth during our physical life on earth. Let us remember what happens to a person during this physical life on earth. It is so wonderful to observe how, as a small child, the human being pours more and more soul power into his physiognomy, into his gaze, into his speech organs. Observing a child as it brings its physicality to life from within is one of the most wonderful observations one can make. For one can make such observations not only with the one-sided theoretical power of the human being, but with the whole human being. But if one could also observe in the same way how the child unconsciously works wisely according to its own inner being, then the wonder one experiences would be a hundredfold too little expressed. Just think how little plastic the child's brain is in early years, how in the first seven years of life an unconscious wisdom works in the child's being to make this brain plastic. And the one who can study this in spiritual science, which I can only hint at in principle today, immerses himself in this inner plastic work of the child, full of wisdom, in the whole organism. And what the child initially sends inwards as a force, almost just fidgeting around, and plasticizes its internal organs, this later connects with actions that are performed outwards, through which one grasps things, orientates oneself in the world; this connects with the sense power. And from all that works within, what is received from the outside, what is experienced with the soul, from all this, what permeates the human being emotionally is formed. The memories and mental images we have of our experiences are only weak reflections of what we really live through, including what we live through unconsciously, what is created within us, which ultimately goes back to the growth forces, to the digestive forces, to the forces of nutrition. When one rises to such an exact inner clairvoyance, one does not merely have a tableau of memories before one, but one has one's own human weaving and shaping, both inwardly in the organism and outwardly in the world. One has oneself before one as a second human being, and one says to oneself from this moment on: you have, in being outwardly in space, your physical spatial body, your physical spatial organization. Everything is interconnected. But you also have a time organization, a time body within you that is not spatially oriented, that is in the process of becoming, that is in the process of shaping, in which the shaping that you send into your inner being grows together with the shaping that you accomplish outwardly under the influence of the other world and of people, which in turn has an effect on you. You see, the realization of this temporal body – that which cannot be painted any more than lightning can be painted; you can capture it for a moment, but you know that it is a temporal process – the of this creative process, which lies behind memory, memory, the stream of consciousness is like on the surface of what one is now looking at, illuminated by its inner sun, in spiritual scientific research one can call this the human etheric body. Do not believe that a level-headed spiritual researcher speaks of the human etheric body as if it were a kind of foggy organization that only permeates this physical body. You can see it, albeit through a kind of fog, through a certain clairvoyance. That is not what it is about. That is what the opponents say. Those who really delve into spiritual science know that the first thing one sees in supersensible knowledge is a process, an event, but a real event. One gets to know oneself as a second being within oneself, which represents a temporal organization. The lasting in our soul life is presented to us in the smallest details, as in a comprehensive tableau. The physical substances we absorb and process internally are replaced every seven to eight years. The physical body is actually subject to constant change, to constant metamorphosis. What I am now pointing to, which can only be grasped by looking inwardly, is a continuous process during our earthly lives. Dear attendees, present-day science worthy of the name proceeds in a precise manner in its external research. The supersensible knowledge that is meant here proceeds in a precise manner in the bringing about of the forces that man needs to see a supersensible world. The development of man is made exact so that, as it were, higher psychic sense organs are obtained, which are precisely manufactured and which can then see the supersensible world. In this way one has not only a theoretical conviction, but a real view of his spiritual being during physical life on earth. One would not yet know anything about the problem of, let us say, the immortality of the soul, which is so close to man. For this a further step is necessary, a further step that demands even more inner soul energy. You see, when you bring ideas into your meditation that you are grounded in, so that you ultimately come to this inner aliveness, which, I would say, gives birth to an inner sun that then illuminates such images that you have to say, after perceiving them, they are real. You really only find something subjective, namely your own experience. That is what you initially feel as real in the images. You have nothing objective yet, you have your own experience, but as reality. This takes it beyond the mathematical. The mathematical gives form to the environment. It contains no reality in itself. What you achieve at this first level of exact clairvoyance allows us to sense an inner reality. And I said that if you scan the images inwardly alive, then they gradually form themselves into a tableau not only of our inner life, but of the formative, growing forces, even of those forces that we develop to effect nutrition, to effect inner nourishment. We get to know ourselves as a second person. This is what we first perceive as a reality in our subjective imaginations, which may be subjective because they initially give us the subjective, our own life in forces, but in reality. But once you have devoted yourself to such strong thinking that you have become capable of looking beyond memories, so to speak, it is much more difficult to remove from your consciousness what you have achieved in your concrete, living thinking. Some people find it difficult to remove images, especially if they are still alive in their soul through emotions, through feelings. Such images, for which one has applied a special effort in order to be able to experience them in the soul, are more difficult to remove. But this too must be learned. Just as one has learned, as it were, to look into a region that otherwise remains completely unconscious, that only brings forth images at the surface of the memory, so one must now learn to develop an inner strength that is more than just forgetting. Then, if I may say so, one must be able to get rid of the strong forces that arise in one through meditation, to be able to erase and remove from one's soul that which one has just first worked into one's soul with all one's strength. One must learn to empty one's consciousness, to empty it completely, so that one only watches. Dear attendees, this is not actually saying little; it is saying a lot. You just need to remember what most people who are untrained in this regard do when they make their consciousness completely empty – they fall asleep; consciousness ceases. Before that, for the visualization I have just described, you must first eliminate all external sensory impressions. But you make the thinking as strong as I have described. Now you must in turn eliminate this strong thinking. The consciousness remains empty; but it remains empty only for moments. If you remain awake, you develop a state of mind that represents only wakefulness. Then the objective external spiritual world, the supersensible world, enters into this alert and empty consciousness; just as the external air for breathing enters into the lungs, so the spiritual world enters into the empty consciousness, which, however, has first been made empty in the way I have described. And in this moment, the first thing we perceive is the spiritual soul that underlies external nature. We learn to recognize that just as our time body lies behind our memory and is the creative element in us in our earthly existence, we learn to recognize that spirit beings are hidden everywhere behind the nature that appears to us in sensory perceptions. Just as we enter a sensory world through our eyes, through our ears, through our other sensory organs, so we enter a spiritual world through the soul being that has been prepared in this way, where we become, so to speak, completely soul-eyed for our spiritual surroundings; we enter a spiritual world, a world of spiritual beings and spiritual processes. We really get to know a spiritual cosmos. And we then realize very soon that what we have had earlier as level-headed people in sensory perception, can be brought into a context with what we now know as the spiritual world. The ordinary visionary rises, so to speak, from his ordinary consciousness into another, where he gets to know all kinds of dream-like things, but knows no context. The person who comes to exact clairvoyance in the way I have described retains his old consciousness alongside the new one he has attained. He can constantly check what he sees in the spiritual world against what he has been given here in the physical world. This is the difference between the spiritual researcher and the visionary. The visionary, when he lives in his visions, has completely forgotten his ordinary human self, because he would not be a visionary if he saw the outer world of the senses as it is seen by the normal person. But the one who is an exact spiritual researcher sees the spiritual world, and at any moment he can put himself back into it in full composure, because, I repeat it again and again: everything I describe here as human development takes place with mathematical composure, as does this putting oneself into the spiritual world in a different consciousness and putting oneself back into the ordinary composure. So that you are able, my dear audience, to say to yourselves: With my outer eye I see the sun. That which I see with my outer eye in the sensual image of the sun is connected to that which I now see spiritually as certain entities of the supersensible world, it is connected to the sun beings in the spiritual world. The physical sun is the physical image of spiritual sun beings, just as my physical body is the physical image of my soul-spiritual being. And so one learns to see a spiritual world behind the physical-sensual one. But then one must go further by developing the strength to remove from consciousness what is within, to empty the consciousness, to wait. One must take this so far that one removes from the temporal body the entire tableau that one first discovered, the creative process during one's life on earth, and that one also removes this, that one completely disregards oneself. So after you have come so far as to see how the forces of growth have shaped your body since childhood, how external experiences have affected it, after you have established what, I would say, lives under the surface of memory, you create it away in a radical abstraction, if I may express it thus, so that our consciousness now not only becomes as empty as I have described, but even more thoroughly empty, in that one's own earth-life, including the supersensible part of one's earth-life, is removed. Then, just as in the case I have just described, when beings who are behind the physical image of the sun come to meet one from the spiritual world, so now, when one's earthly life has been , as an inner experience, but at the same time it lives in a kind of cosmic consciousness. One feels at one with the cosmos, with the consciousness of the world. The pre-earthly existence comes to the fore. You get to know yourself as a spiritual being, as you were before you descended to the physical earth, united as a spiritual being with that which comes from your father and mother, which comes to light in the hereditary current and which forms our physical body, with which we unite. We actually look at this pre-earthly existence. In external science, we have given the view: that which we develop mentally as knowledge comes afterwards, the images that we develop inwardly of the outwardly visible existence come afterwards. If we want to see into the spiritual and supersensible world, we must continue the education we have received in developing scientific concepts by developing our inner soul powers. Then we will be able to turn this development of our inner soul powers into a soul eye. And at the level I have just described, we see into our pre-earthly existence. If I may say so: in present-day external science, things are there first; afterwards comes the theory. What we draw on in forming theories, we bring to inner life. Thus, after the theory, comes the intuition. And we know that it is a reality. You see, the same objection is raised over and over again: Yes, how can you know that what you are now grasping with the empty consciousness is not also your subjective, just an autosuggestion or something like that? Yes, my dear audience, distinguishing mere fantasy from mere perception of reality, only life can do that. It cannot be defined externally, full of life, what the difference is between an imagined hot iron and a real hot iron. The more precisely we imagine the real hot iron, the better it is, the less we make the difference. But the difference arises when we touch the iron. The real hot iron burns us, the imagination does not. We only have to grasp reality in life, and we have to grasp it in life. So if, for example, someone comes, as often happens, and says: But there is also this, that when someone has vividly imagined a lemonade, they have the taste of lemonade in their mouth, so if you really imagine an image as a reality. Such objections are frequently made. One can only say that one should just try to imagine what it is like to look into the pre-earthly existence after the earthly life has been eliminated and to feel the reality of the soul, perhaps through the centuries before it descended to the earthly existence ; and one will no longer say: 'You will have the taste of lemonade through the imagination'; but one will then say, 'Yes, you will have the taste through the imagination, but do you also believe that you can really quench your thirst?' You cannot. You cannot. When you see through all the circumstances of reality and enter into the right context, you will know what is reality and what is mere autosuggestion in a corresponding case. So the reality of the supersensible world must be experienced. But it can be experienced when the abilities to do so are first present in the way described. Now, my dear attendees, I would like to say that we have already presented the one side of the eternity of the human soul, beyond birth or conception. That part of human eternity for which we do not even have a word in the newer languages. We talk about immortality, that is, the duration of the human soul beyond death, but we do not talk about the unborn. We must also talk about it, because one only comprehends eternity when one understands the unborn as well as one understands immortality. But immortality can also be visualized. It can be brought to view by the fact that we now not only train our thinking in meditation, so to speak, to the point of inner energy and concreteness, as I have described it, but also by beginning to train our will. Now, I will only hint again in principle – the more precise details can be found in the books I have mentioned – how to train the will. Consider, for example, that one grasps the will that lies in thinking itself, because thinking is always, when it is not completely passive, a mere brooding, as one's own body broods, when it is inward activity, thinking is always permeated by the will. But we adhere to the external natural processes with this will. We think of what happened earlier first, then what happened later; and when we think dialectically, logically, it is usually only to arrive at what was earlier and what is later in human nature. He who wants to cultivate the will inwardly must, as it were, tear thought away from its adherence to the succession of external nature. It can be done. I will give an example. When we imagine our daily life backwards in the evening, when we imagine what was at five o'clock, was at three o'clock and so on, that is, backwards. So we tear thinking away from the course of nature, in which it runs forward, like the course of nature itself. Or we imagine a melody backwards, or a drama, in as much detail as possible. We remember how we climbed a staircase, imagine ourselves first at the top, then on the penultimate step, and so on, in other words, backwards. When we learn to practice a thought process that runs counter to the course of nature, our will is strengthened. In addition, there may be exercises where we consciously change our habits. Let's be honest, dear attendees, life usually changes us so much that we say to ourselves when we turn 50: we were different when we were 25. But life has taken us over, life has changed us. But you can also take your own development in terms of will into your own hands by exerting inner willpower, so to speak. You can say to yourself: You have to develop a very specific, radically different habit within three or seven years, and you can then work on your will in the most diverse ways. What do you achieve by doing this? Well, my dear audience, what you achieve by doing this is only real if it goes through a bitter feeling of pain. Without going through a bitter, deep pain, you still can't really come to a higher realization. That is the first experience one has: a terrible pain, as if one had become completely alienated from oneself, as if one had plunged the body only into pain. From this pain, another area of higher knowledge then emerges. I can characterize this in the following way: When one has lived oneself into pain to such an extent that one has overcome it, then something has emerged from this culture of will that I can call a spiritual transparency of our own body, of our whole human being. I can explain this by using the eye as an example. What makes the eye the sense organ that we can use so easily? Because it is selfless, because it does not assert its own materiality, it is transparent. The other works in it, which comes from outside. The eye denies itself. In the moment when we get the cataract, the eye asserts its own materiality in the eye. Then the eye becomes selfish. But then we can no longer use it for seeing. Nor can we use our organism for seeing the higher world, just as it is quite right for the physical world. Do not think that I preach asceticism, that would never occur to me. Man should stand with both feet in reality. But he should also allow moments to arise when he makes himself a knower of the supersensible worlds. In such moments, after a person has done such exercises as I have described, the person can make their entire body like a single transparent, but soul-transparent, sensory organ. Otherwise, a person experiences themselves as a human being in their bodily organs. Now, as a result of such exercises of will, one no longer experiences one's bodily organs as one really stands outside one's body with one's experience. The body becomes transparent to the soul. And this separation from the body, this possibility of being outside the body and yet not sleeping, but having a consciousness outside the body, so that one can then see one's own body from the outside, that it is an object, not a subject, this can only be achieved by first acquiring the ability to divest oneself of one's body. But this can only be achieved through the pain described. You have to go through this pain, then the culture of will leads you not only to have exact clairvoyance, as I have described, but to experience how you can also do something in the spiritual world. You notice this from the following: When a person falls asleep in the ordinary course of the day, his consciousness passes into the unconscious. One cannot say, from external observation, that the physical organism of the person has not simply taken on other functions, which simply, as one extinguishes a flame, extinguish consciousness, because consciousness arises again through another metamorphosis of functions when one wakes up. This cannot be said from ordinary research. But the one who has come to the stage of supersensible seeing, which I have just described, knows that the actual spiritual-soul aspect emerges from the physical body when one falls asleep, only it does not have the strength to perceive one thing or another in the world of the spirit, in which it was now, in ordinary life. Now, after going through a culture of will and, first of all, a culture of thought-images, one also learns to look into the real being that one is outside of one's body every night during sleep. And now one learns to recognize what the soul does with this being. Now one learns to recognize that in everyday life one is unconsciously asleep. And that which sleeps, one looks at with the acquired supersensible knowledge as that which exists in sleep outside of the physical body, And one now learns to recognize: When you go through the gate of death, then, then this, what you have unconsciously created, remains. It is your actual humanity, your moral deeds. That which you have acquired in your soul in your dealings with the world and with people as a moral quality becomes real in this being, which separates from you in every state of sleep. But this is also something that is independent of your body; because you have learned to experience outside of the body, you also learn to recognize death in the image. One learns to recognize oneself in what one otherwise is every night and what can exist without the body. And by now having in the supersensible picture of knowledge in real perception what one is without the body, one learns to recognize death, one learns to recognize the overcoming of death by the human soul, one learns to know the other side of the human being, one learns to know immortality in its real contemplation. By making the body transparent to the soul in the way described, one learns to be without the body, one learns to be in the spiritual world through what one has become without the body, and one knows how one has discarded the physical body to be in a spiritual world after death. One has become familiar with the soul's inner work, which is purely spiritual and prepares both the future worlds and one's own future earthly lives. Idealistic magic has been added to exact clairvoyance, the inner work. One consciously learns what is otherwise only unconsciously practiced. Anyone who, as so many often do in this day and age, speaks of an external magic is simply a charlatan. The one who speaks with inner religious feeling to science of the present day of magic, speaks of exact clairvoyance, of idealistic magic, in that one gets to know that which is created within physical life on earth and what then lives beyond death in further stages of existence in order to prepare later lives on earth. What I have tried to show with these discussions, dear attendees, is the relationship between supersensible knowledge, as it is meant in anthroposophy, and contemporary science. I wanted to show how this anthroposophical spiritual science is aware that it has to prove its legitimacy to contemporary science every moment. And let us consider how this science of the present day, in relation to external knowledge, has managed to recognize precisely that which does not include the human being, in that the human being, by making the renunciation described at the beginning of my discussion today, has renounced the need to be objective and initially uses thinking only as a servant. But what one has acquired in serving thinking gives one the attitude to make this thinking so inwardly alive that it fulfills it. For exact clairvoyance, renunciation gives one the powers that the soul has in the will to call upon for real activity, an activity, however, that works in the spirit, that has nothing to do with the physical and sensual existence of man, but that goes beyond death. So that we get to know the eternal part of the human soul, and get to know both the unborn and the immortal, through a realization that really looks like a genuine continuation of what man acquires as sensory knowledge. But precisely because we get to know what is outside of us through the exact sensory knowledge that has been developed today, we, as clairvoyant human beings, are confronted with a world about which we have to ask ourselves: How does our morality operate in it? Is our morality just a vapor that rises in the purely natural world order, which, according to a modified Kant-Laplacean world creation, transitions to the more complicated, more perfect being, only to sink into heat death, whereby the end of that which arises in us as moral impulses would be given with the general cosmic cemetery? The anthroposophical supersensible knowledge referred to here describes morality as a creative force and places moral impulses on an equal footing with purely naturalistic ones. Through this supersensible knowledge, the human being knows himself in a real world through his moral impulses, through his human morality. He knows that the real world we see with our eyes today is the result of previous spiritual worlds, and that what man brings into his own soul and spirit today as moral impulses — that separates from him in every sleep, that then passes through the gate of death — that this is now the germ of future real worlds. Man feels that he is placed in a moral cosmic order. And through such spiritual knowledge as I have described, he also has the possibility of feeling religiously. For man cannot feel religiously in the face of the moral nature with its mere natural laws. Super sensory knowledge is made necessary precisely by the perfection of our sensory knowledge. If the ancients received a spiritual element at the same time as their senses gave them colors and sounds, we only faithfully receive what our senses give us through our observations and experiments, but we stand there as human beings in the face of this perfect science and ask ourselves: What is our position in the world as sentient, as total human beings? Supernatural knowledge gives us the answer. And because it is true and exact knowledge, it leads man up to the moral sense, to the religious sense, and unites science, morality and religion. Thus, my dear attendees, the necessary acknowledgment of today's science, when unfeignedly and honestly acknowledged, leads to the acknowledgment of genuine supersensible knowledge. And what we gain through supersensible knowledge, we gain, my dear assembled guests, for the human being. The human being has become disinterested in relation to external science, wants to be objective, excludes his subjectivity. This is given back to him just as objectively as external nature is given to us in experimental science, in true exact supersensible knowledge. But with that, our minds are warmed from within by this supersensible knowledge, our wills are made strong. We are imbued with warmth, with strength for life, in which we must have security - if our fate is not to be a sad one - for life, in which we must work powerfully if we are to be right members of the human social order. That is the significance of real supersensible knowledge, that it does not remain merely a theoretical view, that it permeates our minds so that we know we are united with the world and with other people through it in that warmth of life and love that we need to live, that we feel imbued with that energy which engages us in the work of the day and in the labors that are more lasting within our human life on earth. True supersensible knowledge imbues our humanity with powers from the supersensible world. Just as the world is a creation of the spiritual, so we make our own deeds a creature of the spiritual by first taking the spiritual into our humanity. In no way does the supersensible knowledge that is meant here detract from the real external, the true external science of the present. It concedes to this science: Yes, you have found the right ways to recognize the extra-human. You recognize your limitations. One often speaks of the limitations of this science. But these limitations are only those that are drawn from observation in the experiment of the senses. The thinking that we develop in us through this observation, through this experiment, can be further developed. Then we will be able to permeate our inner being, as it is permeated with blood in our physical life, with soul and spiritual forces. Then we will become truly human in the true sense of the word through supersensible knowledge that comes from the spirit. Such knowledge can be investigated if one is only unbiased enough to do so. One need not become a spiritual researcher oneself – which everyone can do to a certain extent, as the books mentioned show – but one need not become one. Just as one does not need to be a painter to feel the beauty of a picture, so one does not need to be a spiritual researcher, but only to surrender to one's unbiased mind, not distracted by any prejudices, not even by science, one will be able to make what the spiritual researcher has to say fruitful for one's life, just as one who is not a painter can understand a picture sensitively. One must be a painter if one wants to paint a picture; one must be a spiritual researcher if one wants to present the truths of the supersensible world. On the other hand, one can understand the picture sensitively, even if one is not a painter. One can understand what the spiritual researcher says if one only devotes one's unprejudiced common sense to it; one will find everything consistent and in harmony with the whole of human life. And supersensible knowledge can be assimilated just as one assimilates astrology or biology or something else, even if one is not oneself an astrologer or a biologist or something of the kind. Supersensible knowledge will lead not only to knowledge of the supersensible and of the outer human, but also to warmth of soul and spiritual power of the human. Man will be able to add to what he has so perfectly recognized – although perfection only exists in an ideal, in any case – man will be able to add to what is extra-human the contemplation of man, after the relative independence with which he has recognized the extra-human. And in all knowledge, in all essentials, however much we may look around us in the world, understandingly, cognitively, in the end, when we are to work, when we are to be effective, and that is what matters, we must still be right people and place right people in a world that has attained a certain perfection through the science of the present. Supernatural knowledge worthy of the name attempts to place right human beings in this world so that they can work through this present-day science. It does so by educating the human being from the spiritual to become a right human being through life itself. |

| 69c. A New Experience of Christ: The Essence of Christianity

18 Feb 1911, Strasburg Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| If, on the other hand, you set up an ideal of the higher self, then it usually remains quite abstract - so colourless and bloodless that it seems quite consumptive to us. For example, what Kant calls the “categorical imperative” could be described as a consumptive ideal. A bloodless idealism! |

| 69c. A New Experience of Christ: The Essence of Christianity

18 Feb 1911, Strasburg Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Dear attendees, When the topics of theosophy or spiritual science arise today, many of our contemporaries still believe that this school of thought has its roots or starting points in some oriental ideas or spiritual experiences that are foreign to our Western culture. And this prejudice is seized upon by those who believe they see in Theosophy or spiritual science something that is opposed to Christianity, or to a deeper understanding of Christianity, in so far as it permeates our entire Occidental spiritual culture. If such an opinion is entertained, it is based, in particular, on the fact that within the theosophical world view, what may be called the doctrine of repeated earthly lives or, as it is also called, the doctrine of reincarnation, is presented as a basic fact. And it is believed that such an idea, that man has to undergo repeated lives on earth, could only have been taken from Buddhism or some other oriental world view. Now, if we make such a presupposition, then the whole position of spiritual science or theosophy in the spiritual life of our time is misunderstood, because what is this idea of repeated earthly lives for modern man, or perhaps it is better to say what can this idea be for today's conditions? Today there is a word that is indeed usually only used in connection with scientific facts, but which has a fascinating effect on the educated of the present - on those people of the present who believe they are at the height of our intellectual life - and that is the word 'development'. Admittedly, today this word is usually only used to refer to the development of external forms, that is, the forms of subordinate living beings up to and including humans. The elaboration of this idea of development for human life, encompassing the whole of human life, including the human soul and spirit, is still rarely thought of today; for if one were to engage with the elaboration of the idea of development for the whole of human , one would gradually have to realize that the same thing that we call the development of the species or genus in the animal kingdom must present itself in humans as the development of the individual individual, of the individual individuality. But this means nothing other than that if we see how the individual species develop apart from one another in the animal world, then we must approach the individual with the same interest as we do the species in the animal kingdom, and we must speak of the development of the individual individuality in the human being. Let us commit this to memory: if we have a healthy mind, we show the same interest in the individual human being as we do in the animal species or genus. We have the same interest in the human being as we do in each individual lion – whether it is the lion's grandfather, father, son, and so on. Therefore, we must think of the same lawfulness that we think of as a law of development in animal species, we must think of it in terms of the individual individuality in the case of human beings. So you can see that in the field of spiritual science we speak of the development of the individual human individuality. And we must come to say: What comes into existence in the human being at birth, what gradually and mysteriously unfolds from the still indeterminate facial features, expressions and gestures of the first childlike age, that is the soul-spiritual of the human being, which confronts us with each individual as something special, as an individual. We cannot attribute this to the inherited qualities of the immediate ancestors alone, but we must imagine this relationship of human life to its causes differently than the relationship of the animal to its ancestors. There we understand everything that lives in the individual animal – the form, the physiognomy – when we understand the species. But with humans it is different. What lives in man, we find in each person in a special, particular way. What has developed in man as a generic characteristic, we attribute to physical inheritance; but what confronts us as his special being, we must attribute to what the person, as the cause of his present life, has gone through in earlier lives, in earlier stages of existence. And what we encounter in the present framework of his personality, that in turn forms the cause, the basis for his work in a later life. Thus we have a living chain of development that goes from life to life, from incarnation to incarnation. And we see everything that comes to us as characteristic of a person in such a way that we see the necessity of tracing it back to earlier soul and spiritual states. Thus Theosophy or spiritual science is able to introduce a law in the higher realm of human life, just as it was incorporated relatively recently into the realm of the natural life of human development. Yes, today's humanity has a short memory. Otherwise it would not be necessary to point out that as late as the seventeenth century not only laymen but also scholars of natural science assumed that lower animals could develop out of decaying river mud without the introduction of germs of life. And it was the great Italian naturalist Francesco Redi who first caused this tremendous upheaval in natural science thinking by stating that living things can only come from living things. Just as this sentence applies to natural life within certain limits, so the other sentence applies to human life within certain limits: spiritual and mental things can only have their origin in spiritual and mental things. And it is only an inaccurate observation if one wants to trace back what works its way out of the vague depths of an adolescent's consciousness from day to day, from week to week, from year to year as a spiritual-soul element to the mere physical line of inheritance of the ancestors – is just as inaccurate an observation as it is inaccurate to trace what lives in animals, even in earthworms, back to the mere laws of the substances that make up river mud just because one has not considered the living germ. It is an inaccurate observation when we speak today only of the inheritance of mental and moral abilities because we do not pay attention to the soul-spiritual core, which integrates that which it can appropriate from the inherited traits in the same way that the living germ of the living being appropriates the substance in which that germ is embedded. Such truths always fare in much the same way in the course of human development. In those days, Francesco Redi only just escaped the fate of Giordano Bruno. Today everyone, from the Haeckelianer to the most radical opponents of Haeckel, will recognize this sentence as self-evident, but only within the limits of external nature, insofar as it concerns the body. At that time, however, the sentence “Living things can only come from living things” was a tremendous heresy. Today, however, heretics are no longer burned. But if one stands on the firm ground of today's scientific facts - while in reality one only stands on the ground of one's preconceived ideas, of contemporary prejudices - one regards the law of repeated earth lives, which is the same for the higher areas of spiritual existence as Redi's sentence that living things can only come from living things, as heresy, as fantasy, as sheer madness. But the time is not far distant when it will be said of this law in the same way: It is really incomprehensible that any man could ever have thought differently. Whence then comes this law of repeated earth-lives? Do we need to go back to some Eastern philosophy of life, must this law be borrowed from Buddhism? No. To understand the law of repeated earthly lives in the context of modern European culture, all that is needed is an unbiased, spirit-searching view that overlooks the facts. And what this view sees has nothing to do with any tradition. Like any other scientific law, it will be accepted by modern spiritual education because, based on the idea of development, it necessarily leads to this law. But anyone who wanted to claim that this could add anything to our Western intellectual development that would run counter to Christianity is not aware of how this entire Western intellectual life is permeated by the living weaving and essence of Christian feeling, of Christian feeling. Indeed, if one is able to observe with an open mind, it can be seen that the way of thinking, the forms of imagination, even of those who today behave as the worst opponents of Christianity, have only been made possible by the education of Western humanity, which they have received through Christianity. Anyone who is willing and able to observe impartially will find that even the most radical opponents of Christianity fight it with arguments borrowed from Christianity itself. But there is a radical difference between the Christian essence and what we can call the pre-Christian essence - a difference that is just not immediately apparent because everything in human development is slow and gradual and always encompasses the earlier in the later. There is something in the pre-Christian world view that is radically different from the Christian one, and this can be found and observed among the oriental world views, even in their most modern form, in Buddhism, for example. We can see this fundamental difference between the essence of Christianity and the oriental feeling and thinking that has found expression in Buddhism if we consider just a few of its aspects. For this purpose, we need only recall a conversation that can be found in Buddhist literature and that is deeply rooted in Buddhist feeling and thinking. By studying such descriptions, we can gain a much more accurate insight into the essence of any world view than by considering its highest tenets and dogmas. After all, one can argue at length about whether this or that is to be understood in terms of Nirvana or Christian bliss. But how that which lives in the Buddhist and Christian way of thinking works its way into people's feelings, and how these feelings then relate to the whole world - the physical and the spiritual world - that is decisive for the value, the meaning and the essence of a world view and for its effect on human souls. In Buddhist literature, we find preserved that remarkable conversation between the legendary King Milinda and the sage Nagasena. In this conversation, it is said that King Milinda came to the sage Nagasena by chariot and wanted to be instructed regarding the nature of the human soul. The sage then asked the king: “Tell me, did you come by chariot or on foot?” “By the chariot,” the king replied. ”Now tell me, when you have the chariot before you, what do you have there before you? You have the shafts, the body of the chariot, and the wheels before you. Is the shaft the chariot? Is the body the chariot? Are the wheels the chariot? No! Is that all you have in front of you? There is also the seat of the chariot! And what else do you have in front of you? Nothing! The chariot is therefore only a name or a form, because the realities that are in front of you are the box, the shaft, the wheels and the seat. What else is there is only name and form. Just as only a name or a form holds the individual parts together – wheels, shaft, body and seat – so too the individual abilities, feelings, thoughts and perceptions of the human soul are held together not by something that can be described as a particular reality, but only by a name or a form. So it can be said – felt in the right Buddhist sense: A central being in man, which holds together the individual human soul abilities, cannot be found, just as little as anything other than name and form can be found except for the drawbar, the wagon body, the seat and the wheels on the wagon. And through yet another simile, the wise man made clear to [the king] the nature of the soul, saying: Consider the mango fruit – it comes from the mango tree. You know that the mango tree is only there because another mango fruit was there before, from which it was created. The mango plant comes from the mango fruit, which has rotted in the earth. What can you say about the mango fruit? It comes from the rotten seed. Now follow the path from the old fruit to the new mango plant. What does the new plant have in common with the old plant other than its name or shape? — But it is the same with the soul's existence, said the wise Nagasena to King Milinda. [It was also there only in name!] It was also a law of experience in Buddhism that a person undergoes repeated earthly lives. But this law did not prompt the actual central Buddhist feeling to seek and see something other than name and form in what passes from one life to another, just as with a mango fruit, where nothing passes from one to the other except name and form. Thus, according to the Buddhist view, we can see the effects of past lives in what we call our destiny in a life – our abilities, talents and so on. But no central soul-being passes over from the earlier life to the new one; only causes work out into effects, and what we have in common in one life with an earlier life – except for what we feel to be our destiny in the new life – is only name and form. You have to feel your way through what is actually at hand in Buddhism. And now we could – in order to remain objective – translate that which appears to us in this story as the correct Buddhist feeling by transferring the whole thing into the Christian sense. What would the two stories sound like in a Christian sense? They don't exist, but let's try to translate them and thereby make the difference very clear. A Christian sage would say something like this: Take a look at the chariot – when you look at it, you see the shafts, the body, the wheels and whatever else is on the outside. The chariot seems to you to be only name and form, but try to see if you can travel on a name or a form; you can't get anywhere in the world on that. Nevertheless, although only name and form are there for the visible, there is something else besides the body of the wagon, the shaft and the wheels and so on, which signifies a reality when a wagon stands before us and not just its parts. As I said, there is no such Christian legend, but a Christian-minded person felt this when he coined the phrase “parts”, which the scientifically minded person often has in his hand, but for which he lacks the context, when he said: