| 260. The Christmas Conference : Rudolf Steiner's Opening Lecture and Reading of the Statutes

24 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| We begin our Christmas Conference for the founding of the Anthroposophical Society in a new form with a view of a stark contrast. |

| Let us bring it into life above all during this our Christmas Conference. Let us during this our Christmas Conference make the shining forth of the universal light—as it shone before the shepherds, who bore within them only the simplicity of their hearts, and before the kingly magi, who bore within them the wisdom of all the universe—let us make this flaming Christmas light, this universal light of Christmas into a symbol for what is to come to pass through our own hearts and souls! |

| In recent weeks I have pondered deeply in my soul the question: What should be the starting point for this Christmas Conference, and what lessons have we learnt from the experiences of the past ten years since the founding of the Anthroposophical Society? |

| 260. The Christmas Conference : Rudolf Steiner's Opening Lecture and Reading of the Statutes

24 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

We begin our Christmas Conference for the founding of the Anthroposophical Society in a new form with a view of a stark contrast. We have had to invite you, dear friends, to pay a visit to a heap of ruins. As you climbed up the Goetheanum hill here in Dornach your eyes fell on our place of work, but what you saw were the ruins of the Goetheanum which perished a year ago. In the truest sense of the word this sight is a symbol that speaks profoundly to our hearts, a symbol not only of the external manifestation of our work and endeavour on anthroposophical ground both here and in the world, but also of many symptoms manifesting in the world as a whole. Over the last few days, a smaller group of us have also had to take stock of another heap of ruins. This too, dear friends, you should regard as something resembling the ruins of the Goetheanum, which had become so very dear to us during the preceding ten years. We could say that a large proportion of the impulses, the anthroposophical impulses, which have spread out into the world over the course of the last twenty years made their initial appearance in the books—perhaps there were too many of them—of our publishing company, the Philosophisch-Anthroposophischer Verlag in Berlin. You will understand, since twenty years of work are indeed tied up in all that can be gathered under the heading ‘Philosophisch-Anthroposophischer Verlag,’ that all those who toiled to found and carry on the work of this publishing company gave of the substance of their hearts. As in the case of the Goetheanum, so also as far as the external aspect of this Philosophisch-Anthroposophischer Verlag is concerned, we are faced with a heap of ruins.24 In this case it came about as a consequence of the terrible economic situation prevailing in the country where it has hitherto had its home. All possible work was prevented by a tax situation which exceeded any measures which might have been taken and by the rolling waves—quite literally—of current events which simply engulfed the publishing company. Frau Dr Steiner has been busy over the last few weeks preparing everything anchored in this Philosophisch-Anthroposophischer Verlag for its journey here to the Goetheanum in Dornach. You can already see a small building25 coming into being lower down the hill between the Boiler House and the Glass House. This will become the home of the Philosophisch-Anthroposophischer Verlag, or rather of its stock of books, which in itself externally also resembles a heap of ruins. What can we do, dear friends, but link the causes of these heaps of rubble with world events which are currently running their course? The picture we see at first seems grim. It can surely be said that the flames which our physical eyes saw a year ago on New Year's Eve blazed heavenwards before the eyes of our soul. And in spirit we see that in fact these flames glow over much of what we have been building up during the last twenty years. This, at first, is the picture with which our souls are faced. But it has to be said that nothing else at present can so clearly show us the truth of the ancient oriental view that the external world is maya and illusion. We shall, dear friends, establish a mood of soul appropriate for this our Christmas Foundation Conference if we can bring to life in our hearts the sense that the heap of ruins with which we are faced is maya and illusion, and that much of what immediately surrounds us here is maya and illusion. Let us take our start from the immediate situation here. We have had to invite you to take your places in this wooden shed.26 It is a temporary structure we have hurriedly put up over the last two days after it became clear how very many of our friends were expected to arrive. Temporary wooden partitions had to be put up next door. I have no hesitation in saying that the outer shelter for our gathering resembles nothing more than a shack erected amongst the ruins, a poor, a terribly poor shack of a home. Our initial introduction to these circumstances showed us yesterday that our friends felt the cold dreadfully in this shed, which is the best we can offer. But dear friends, let us count this frost, too, among the many other things which may be regarded as maya and illusion in what has come to meet you here. The more we can find our way into a mood which feels the external circumstances surrounding us to be maya and illusion, the more shall we develop that mood of active doing which we shall need here over the next few days, a mood which may not be negative in any way, a mood which must be positive in every detail. Now, a year after the moment when the flames of fire blazed skywards out of the dome of our Goetheanum, now everything which has been built up in the spiritual realm in the twenty years of the Anthroposophical Movement may appear before our hearts and before the eyes of our soul not as devouring flames but as creative flames. For everywhere out of the spiritual content of the Anthroposophical Movement warmth comes to give us courage, warmth which can be capable of bringing to life countless seeds for the spiritual life of the future which lie hidden here in the very soil of Dornach and all that belongs to it. Countless seeds for the future can begin to unfold their ripeness through this warmth which can surround us here, so that one day they may stand before the world as fully matured fruits as a result of what we want to do for them. Now more than ever before we may call to mind that a spiritual movement such as that encompassed by the name of Anthroposophy, with which we have endowed it, is not born out of any earthly or arbitrary consideration. At the very beginning of our Conference I therefore want to start by reminding you that it was in the last third of the nineteenth century that on the one hand the waves of materialism were rising while out of the other side of the world a great revelation struck down into these waves, a revelation of the spirit which those whose mind and soul are in a receptive state can receive from the powers of spiritual life. A revelation of the spirit was opened up for mankind. Not from any arbitrary earthly consideration, but in obedience to a call resounding from the spiritual world; not from any arbitrary earthly consideration, but through a vision of the sublime pictures given out of the spiritual world as a modern revelation for the spiritual life of mankind, from this flowed the impulse for the Anthroposophical Movement.27 This Anthroposophical Movement is not an act of service to the earth. This Anthroposophical Movement in its totality and in all its details is a service to the divine beings, a service to God. We create the right mood for it when we see it in all its wholeness as a service to God. As a service to God let us take it into our hearts at the beginning of our Conference. Let us inscribe deeply within our hearts the knowledge that this Anthroposophical Movement desires to link the soul of every individual devoted to it with the primeval sources of all that is human in the spiritual world, that this Anthroposophical Movement desires to lead the human being to that final enlightenment—that enlightenment which meanwhile in human earthly evolution is the last which gives satisfaction to man—which can clothe the newly beginning revelation in the words: Yes, this am I as a human being, as a God-willed human being on the earth, as a God-willed human being in the universe. We shall take our starting point today from something we would so gladly have seen as our starting point years ago in 1913.28 This is where we take up the thread, my dear friends, inscribing into our souls the foremost principle of the Anthroposophical Movement, which is to find its home in the Anthroposophical Society, namely, that everything in it is willed by the spirit, that this Movement desires to be a fulfilment of what the signs of the times speak in a shining script to the hearts of human beings. The Anthroposophical Society will only endure if within ourselves we make of the Anthroposophical Movement the profoundest concern of our hearts. If we fail, the Society will not endure. The most important deed to be accomplished during the coming days must be accomplished within all your hearts, my dear friends. Whatever we say and hear will only become a starting point for the cause of Anthroposophy in the right way if our heart's blood is capable of beating for it. My friends, for this reason we have brought you all together here: to call forth a harmony of hearts in a truly anthroposophical sense. And we allow ourselves to hope that this is an appeal which can be rightly understood. My dear friends, call to mind the manner in which the Anthroposophical Movement came into being. In many and varied ways there worked in it what was to be a revelation of the spirit for the approaching twentieth century. In contrast to so much that is negative, it is surely permissible to point emphatically here to the positive side: to the way in which the many and varied forms of spiritual life, which flowed in one way or another into the inner circles of outer society, genuinely entered into the hearts of our dear anthroposophical friends. Thus at a certain point we were able to advance far enough to show in the Mystery Dramas how intimate affairs of the human heart and soul are linked to the grand sweep of historical events in human evolution. I do believe that during those four or five years—a time much loved and dear to our hearts—when the Mystery Dramas were performed in Munich,29 a good deal of all that is involved in this link between the individual human soul and the divine working of the cosmos in the realms of soul and spirit did indeed make its way through the souls of our friends. Then came something of which the horrific consequences are known to every one of you: the event we call the World War. During those difficult times, all efforts had to be concentrated on conducting the affairs of Anthroposophy in a way which would bring it unscathed through all the difficulties and obstacles which were necessarily the consequence of that World War. It cannot be denied that some of the things which had necessarily to be done out of the situation arising at the time were misunderstood, even in the circles of our anthroposophical friends. Not until some future time will it be possible for more than a few people to form a judgment on those moods which caused mankind to be split into so many groups over the last decade, on those moods which led to the World War. As yet there exists no proper judgment about the enormity which lives among us all as a consequence of that World War. Thus it can be said that the Anthroposophical Society—not the Movement—has emerged riven from the War. Our dear friend Herr Steffen has already pointed out a number of matters which then entered into our Anthroposophical Society and in no less a manner also led to misunderstandings. Today, however, I want to dwell mainly on all that is positive. I want to tell you that if this gathering runs its course in the right way, if this gathering really reaches an awareness of how something spiritual and esoteric must be the foundation for all our work and existence, then those spiritual seeds which are everywhere present will be enabled to germinate through being warmed by your mood and your enthusiasm. Today we want to generate a mood which can accept in full earnestness that external things are maya and illusion but that out of this maya and illusion there germinates to our great joy—not a joy for our weakness but a joy for our strength and for the will we now want to unfold—something that can live invisibly among us, something that can live in innumerable seeds invisibly among us. Prepare your souls, dear friends, so that they may receive these seeds; for your souls are the true ground and soil in which these seeds of the spirit may germinate, unfold and develop. They are the truth. They shine forth as though with the shining of the sun, bathing in light all the seeming ruins encountered by our external eyes. Today, of all days, let us allow the profoundest call of Anthroposophy, indeed of everything spiritual, to shine into our souls: Outwardly all is maya and illusion; inwardly there unfolds the fullness of truth, the fullness of divine and spiritual life. Anthroposophy shall bring into life all that is recognized as truth within it. Where do we bring into life the teaching of maya and of the light of truth? Let us bring it into life above all during this our Christmas Conference. Let us during this our Christmas Conference make the shining forth of the universal light—as it shone before the shepherds, who bore within them only the simplicity of their hearts, and before the kingly magi, who bore within them the wisdom of all the universe—let us make this flaming Christmas light, this universal light of Christmas into a symbol for what is to come to pass through our own hearts and souls! All else that is to be said I shall say tomorrow when what we shall call the laying of the Foundation Stone of the Anthroposophical Society takes place. Now I wish to say this, my dear friends. In recent weeks I have pondered deeply in my soul the question: What should be the starting point for this Christmas Conference, and what lessons have we learnt from the experiences of the past ten years since the founding of the Anthroposophical Society? Out of all this, my dear friends, two alternative questions arose. In 1912, 1913 I said for good reasons that the Anthroposophical Society would now have to run itself, that it would have to manage its own affairs, and that I would have to withdraw into a position of an adviser who did not participate directly in any actions. Since then things have changed. After grave efforts in the past weeks to overcome my inner resistance I have now reached the realization that it would become impossible for me to continue to lead the Anthroposophical Movement within the Anthroposophical Society if this Christmas Conference were not to agree that I should once more take on in every way the leadership, that is the presidency, of the Anthroposophical Society to be founded here in Dornach at the Goetheanum. As you know, during a conference in Stuttgart30 it became necessary for me to make the difficult decision to advise the Society in Germany to split into two Societies, one which would be the continuation of the old Society and one in which the young members would chiefly be represented, the Free Anthroposophical Society. Let me tell you, my dear friends, that the decision to give this advice was difficult indeed. It was so grave because fundamentally such advice was a contradiction of the very foundations of the Anthroposophical Society. For if this was not the Society in which today's youth could feel fully at home, then what other association of human beings in the earthly world of today was there that could give them this feeling! Such advice was an anomaly. This occasion was perhaps one of the most important symptoms contributing to my decision to tell you here that I can only continue to lead the Anthroposophical Movement within the Anthroposophical Society if I myself can take on the presidency of the Anthroposophical Society, which is to be newly founded. You see, at the turn of the century something took place very deeply indeed within spiritual events, and the effects of this are showing in the external events in the midst of which human beings stand here on earth. One of the greatest possible changes took place in the spiritual realm. Preparation for it began at the end of the 1870s, and it reached its culmination just at the turn of the century. Ancient Indian wisdom pointed to it, calling it the end of Kali Yuga. Much, very much, my dear friends, is meant by this. And when in recent times I have met in all kinds of ways with young people in all the countries of the world accessible to me, I have had to say to myself over and over again: Everything that beats in these youthful hearts, everything which glows towards spiritual activity in such a beautiful and often such an indeterminate way, this is the external expression for what came to completion in the depths of spiritual world-weaving during the last third of the nineteenth century leading up to the twentieth century. My dear friends, what I now want to say is not something negative but something positive so far as I am concerned: I have frequently found, when I have gone to meet young people, that their endeavours to join one organization or another encountered difficulties because again and again the form of the association did not fit whatever it was that they themselves wanted. There was always some condition or other as to what sort of a person you had to be or what you had to do if you wanted to join any of these organizations. This is the kind of thing that was involved in the feeling that the chief disadvantage of the Theosophical Society—out of which the Anthroposophical Society grew, as you know—lay in the formulation of its three tenets.31 You had to profess something. The way in which you had to sign a form, which made it look as though you had to make some dogmatic assertion, is something which nowadays simply no longer agrees with the fundamental mood of human souls. The human soul today feels that anything dogmatic is foreign to it; to carry on in any kind of a sectarian way is fundamentally foreign to it. And it cannot be denied that within the Anthroposophical Society it is proving difficult to cast off this sectarian way of carrying on. But cast it off we must. Not a shred must be allowed to remain within the new Anthroposophical Society which shall be founded. This must become a true world society. Anyone joining it must feel: Yes, here I have found what moves me. An old person must feel: Here I have found something for which I have striven all my life together with other people. The young person must feel: Here I have found something which comes out to meet my youth. When the Free Anthroposophical Society was founded I longed dearly to reply to young people who enquired after the conditions for joining it with the answer which I now want to give: The only condition is to be truly young in the sense that one is young when one's youthful soul is filled with all the impulses of the present time. And, dear friends, how do you go about being old in the proper sense in the Anthroposophical Society? You are old in the proper sense if you have a heart for what is welling up into mankind today both for young and old out of spiritual depths by way of a universal youthfulness, renewing every aspect of our lives. By hinting at moods of soul I am indicating what it was that moved me to take on the task of being President of the Anthroposophical Society myself. This Anthroposophical Society—such things can often happen—has been called by a good many names. Thus, for example, it has been called the ‘International Anthroposophical Society’. Dear friends, it is to be neither an international nor a national society. I beg you heartily never to use the word ‘international society’ but always to speak simply of a ‘General Anthroposophical Society’ which wants to have its centre here at the Goetheanum in Dornach. You will see that the Statutes are formulated in a way that excludes anything administrative, anything that could ever of its own accord turn into bureaucracy. These Statutes are tuned to whatever is purely human. They are not tuned to principles or to dogmas. What these Statutes say is taken from what is actual and what is human. These Statutes say: Here in Dornach is the Goetheanum. This Goetheanum is run in a particular way. In this Goetheanum work of this kind and of that kind is undertaken. In this Goetheanum endeavours are made to promote human evolution in this way or in that way. Whether these things are ‘right’ or ‘not right’ is something that must not be stated in statutes which are intended to be truly modern. All that is stated is the fact that a Goetheanum exists, that human beings are connected with this Goetheanum, and that these human beings do certain things in this Goetheanum in the belief that through doing so they are working for human evolution. Those who wish to join this Society are not expected to adhere to any principle. No religious confession, no scientific conviction, no artistic intention is set up in any dogmatic way. The only thing that is required is that those who join should feel at home in being linked to what is going on at the Goetheanum. In the formulation of these Statutes the endeavour has been made to avoid establishing principles, so that what is here founded may rest on all that is purely human. Look carefully at the people who will make suggestions with regard to what is to be founded here over the next few days. Ask yourselves whether you can trust them or not. And if at this Foundation Meeting you declare yourselves satisfied with what wants to be brought about in Dornach, then you will have declared yourselves for something that is a fact; then you will have declared yourselves to be in tune with something that is a fact. If this is possible, everything else will follow on. Yes, everything will run its course. Then it will not be necessary for the centre at Dornach to designate or nominate a whole host of trustees; then the Anthroposophical Society will be what I have often pointed to when to my deep satisfaction I have been permitted to be present at the founding of the individual national Societies.32 Then the Anthroposophical Society will be something that can arise independently on the foundation of all that has come into being in these national Societies. If this can come about, then these national Societies will be truly autonomous too. Then every group which comes into being within this Anthroposophical Society will be truly autonomous. In order to reach this truly human standpoint, my dear friends, we must realize that especially in the case of a Society which is built on spiritual foundations, in the way I have described, we shall come up against two difficulties. We must overcome these difficulties here, so that in future they will no longer exist in the way they existed in the past history of the Anthroposophical Society. One of these difficulties is the following: Everyone who understands the consciousness of today will, I believe, agree that this present-day consciousness demands that whatever takes place should do so in full public view. A Society built on firm foundations must above all else not offend this demand of our time. It is not at all difficult to prefer secrecy, even in the external form, in one case or another. But whenever a Society like ours, built on a foundation of truth, seriously desires secrecy, it will surely find itself in conflict with contemporary consciousness, and the most dire obstacles for its continuing existence will ensue. Therefore, dear friends, for the General Anthroposophical Society which is to be founded we cannot but lay claim to absolute openness. As I pointed out in one of my very first essays in Luzifer-Gnosis,33 the Anthroposophical Society must stand before the world just like any other society that may be founded for, let us say, scientific or similar purposes. It must differ from all these other societies solely on account of the content that flows through its veins. The form in which people come together in it can, in future, no longer be different from that of any other society. Picture to yourselves what we can shovel out of the way if we declare from the start that the Anthroposophical Society is to be entirely open. It is essential for us to stand firmly on a foundation of reality, that is on the foundation of present-day consciousness. This will mean, dear friends, that in future we shall have to handle our lecture cycles in a manner that differs greatly from that to which we have been accustomed in the past. The history of these lecture cycles represents a tragic chapter within the development of our Anthroposophical Society. They were first published in the belief that they could be retained within a given circle; they were printed for the members of the Anthroposophical Society. But we have long been in a situation in which our opponents, so far as the public declaration of the content is concerned, are far more interested in the cycles than are the members of the Society themselves. Do not misunderstand me; I do not mean that the members of our Society do not work inwardly with the lecture cycles, for they do. But their work is inward, it remains egoistic, a nice Society egoism. The interest which sends its waves out into the world, the interest which gives our Society its particular stamp in the world, this interest comes towards the cycles from our opponents. It has been known to happen that as little as three weeks after its publication a lecture cycle is already being quoted in the worst kind of publication brought out by the opposition. To continue in our old ways as regards the lecture cycles would be to hide our head in the sand, believing that because everything is dark for us everything must be dark in the outside world too. That is why I have been asking myself for years what can be done about the cycles. We now have no alternative but to put up a moral barrier in place of the physical barrier we tried to erect earlier on, which has meanwhile been breached at all manner of points. In the draft of the Statutes I have endeavoured to do just this. In future all the cycles, without exception, are to be sold publicly, just like any other books. But suppose, dear friends, there was a book about the integration of partial differential equations. For a great many people such a book is very esoteric indeed. I am probably not wrong in assuming that among those of you gathered here in these two rooms today there is only an extremely small esoteric circle of individuals who might fruitfully concern themselves with the integration of partial differential equations, or of linear differential equations. The book, however, may be sold to anybody. But supposing someone who knows nothing of partial differential equations and is incapable of differentiating or integrating anything at all, someone who knows nothing about logarithms, were to find a textbook on the subject belonging to one of his sons. He would look inside it, see rows and rows of figures but not understand a thing. Then suppose his sons were to tell him that all these figures were the street numbers of the houses in every city in the world. He might well think to himself: What a useful thing to learn; now if I go to Paris I shall know the street number of all the different houses. As you see, there is no harm in the judgment of someone who understands nothing of the matter, for he is a dilettante, an amateur. In this instance life itself draws the line between the capacity to judge and the lack of capacity to judge. Thus as regards anthroposophical knowledge we can at least try to draw the line morally and no longer physically. We sell the cycles to all who wish to have them but declare from the start who can be considered competent to form a valid judgment on them, a judgment by which we can set some store. Everybody else is an amateur as far as the cycles are concerned. And we also declare that in future we shall no longer take any account of judgments passed on the cycles by those who are amateurs. This is the only moral protection available to us. If only we carry it out properly, we shall bring about a situation in which the matters with which we are concerned are treated just as are books about the integration of partial differential equations. People will gradually come to agree that it is just as absurd for someone, however learned in other spheres, to pass a judgment about a lecture cycle as it is for someone who knows nothing of logarithms to say: This book about partial differential equations is stuff and nonsense! We must bring about a situation in which the distinction between an amateur and an expert can be drawn in the right way. Another very great difficulty, dear friends, is the fact that the impulses of the Anthroposophical Movement are not everywhere thoroughly assessed in the right way. Judgments are heard here and there which absolutely deny the Anthroposophical Movement by seeing it as something that is parallel to the very things it is supposed to replace in human evolution. Only a few days ago somebody once again said to me: If you speak to such and such a group of people about what Anthroposophy has to offer, even those who work only in the practical realm accept it so long as you don't mention Anthroposophy or the threefold social order by name; you have to disown them. This is something that has been done by a great many people for many years, and it could not be more false. Whatever the realm, we must stand in the world under the sign of the full truth as representatives of the essence of Anthroposophy. We must be aware that if we are incapable of doing so we cannot actually further the aims of the Anthroposophical Movement. Any veiled representation of the Anthroposophical Movement leads in the end to no good. Of course everything is individual in such matters. Not everything can be made to conform to a single pattern. Let me give you a few examples of what I mean. Take eurythmy. As I said yesterday before the performance, eurythmy is drawn and cultivated from the very depths of Anthroposophy. We have to be aware that, imperfect though it still is, it places something in the world which is entirely new, something original which can in no way be compared with anything else that may seem to resemble it in the world today. We have to muster enough enthusiasm for our cause to enable us to exclude any external, superficial comparisons. I know how a sentence like this can be misunderstood, but nevertheless I say it to you in this circle, my dear friends, for it expresses one of the fundamental conditions required for the prospering of the Anthroposophical Movement within the Anthroposophical Society. Similarly, I have sweated much blood lately—I speak symbolically, of course—over the new form of recitation and declamation which Frau Dr Steiner has developed in our Society. As with eurythmy, the nerve-centre of this form of declaiming or reciting is what is drawn and cultivated from the very depths of Anthroposophy, and it is with this nerve-centre that we must concern ourselves. This nerve-centre is what we have to recognize and there is no point in believing that the result can be improved by taking on board any bits and pieces which might also be good, or even better, belonging to similar methods elsewhere. It is of this absolutely new, this primary quality that we must be aware in all the realms of Anthroposophy. Now a third example: A realm in which Anthroposophy can be especially fruitful is that of medicine. Yet Anthroposophy will quite definitely remain unfruitful in the realm of medicine, especially therapy, if the tendency persists to represent matters within the field of medicine in the Anthroposophical Movement in a manner which meets with the approval of those who represent medicine in the ordinary way today. We must carry Anthroposophy courageously into every realm, including medicine. Only then will we make progress in what eurythmy ought to be, in what recitation and declamation ought to be, in what medicine ought to be, not to mention many other different fields living within our Anthroposophical Society, just as we must make progress with Anthroposophy itself in the strict sense of the term. Herewith I have at least hinted at the fundamental conditions which must be placed before our hearts at the beginning of our Conference for the founding of the General Anthroposophical Society. In the manner indicated it must become a Society of attitudes and not a Society of statutes. The Statutes are to express externally what is alive within every soul. So now I would like to proceed to the reading34 of the draft of the StatutesA which go in the direction I have thus far mentioned in brief. STATUTES OF THE ANTHROPOSOPHICAL SOCIETY’

This paragraph is of particular concern to me because wherever I go members with a good capacity to judge have been saying to me: We never seem to hear what is going on in the Anthroposophical Society. By instituting this journal we shall be able to conduct a careful correspondence which will more and more come to be a correspondence belonging to each one of you, and through it you will be able to live right in the midst of the Anthroposophical Society. Now, my dear friends, in case after due consideration you should indeed come to agree with my appointment as President of the Anthroposophical Society, I still have to make my suggestions as to the membership of the Vorstand with whom I should actually be able to fulfil the tasks which I have indicated very briefly here. So that the affairs of Anthroposophy can be truly and properly administered, members of the Vorstand must be people who reside here in Dornach. So far as my estimation of the Society is concerned, the Vorstand cannot consist of individuals who are situated all over the place. This will not prevent the individual groups from electing their own officials autonomously. And when these officials come to Dornach, they will be taken into the meetings of the Vorstand as advisory members while they are here. We must make the whole thing come to life. Instead of a bureaucratic Vorstand scattered all over the world there will be officials responsible for the individual groups, officials arising from amongst the membership of the groups; they will always have the opportunity to feel themselves equal members of the Vorstand which, however, will be located in Dornach. The work itself will have to be taken care of by the Vorstand in Dornach. Moreover, the members of the Vorstand must without question be people who have devoted their lives entirely, both outwardly and inwardly, to the cause of Anthroposophy. So now after long deliberations over the past weeks I shall take the liberty of presenting to you my suggestions for the membership of the Vorstand: I believe there will nowhere arise even the faintest hint of dissension but that on the contrary there will be in all your hearts the most unanimous and fullest agreement to the suggestion that Herr Albert Steffen be appointed as Vice-president. (Lively applause) This being the case, we have in the Vorstand itself an expression of something I have already mentioned today: our links, as the Anthroposophical Society, with Switzerland. I cannot express my conviction more emphatically than by saying to you: If it is a matter of having a Swiss citizen who will give all his strength as a member of the Vorstand and as Vice-president, then there is no better Swiss citizen to be found. Next we shall have in the Vorstand an individual who has been united with the Anthroposophical Society from the very beginning, who has for the greater part built up the Anthroposophical Society and who is today active in an anthroposophical way in one of the most important fields: Frau Dr Steiner. (Lively applause) With your applause you have said everything and clearly shown that we need have no fear that our choice in this direction might not have been quite appropriate. A further member of the Vorstand I have to suggest on the basis of facts arising here over recent weeks. This is the person with whom I at present have the opportunity to test anthroposophical enthusiasm to its limits in the right way by working with her on the elaboration of the anthroposophical system of medicine: Frau Dr Ita Wegman. (Lively applause) Through her work—and especially through her understanding of her work—she has shown that in this specialized field she can assert the effectiveness of Anthroposophy in the right way. I know that the effects of this work will be beneficial. That is why I have taken it upon myself to work immediately with Frau Dr Wegman on developing the anthroposophical system of medicine.37 It will appear before the eyes of the world and then we shall see that particularly in members who work in this way we have the real friends of the Anthroposophical Society. Another member I have to suggest is one who has been tried and tested in the utmost degree for the work in Dornach both in general and down to the very last detail, one who has ever proved herself to be a faithful member. I do believe—without intending to sound boastful—that the members of the Vorstand have indeed been rightly selected. Albert Steffen was an anthroposophist before he was even born, and this ought to be duly recognized. Frau Dr Steiner has of course always been an anthroposophist ever since an Anthroposophical Society has existed. Frau Dr Wegman was one of the very first members who joined in the work just after we did in the very early days. She has been a member of the Anthroposophical Movement for over twenty years. Apart from us, she is the longest standing member in this room. And another member of very long standing is the person I now mean, who has been tried and tested down to the very last detail as a most faithful colleague; you may indeed be satisfied with her down to the very last detail: Fräulein Dr Lili Vreede. (Applause) We need furthermore in the anthroposophical Vorstand an individual who will take many cares off our shoulders, cares which cannot all be borne by us because of course the initiatives have to be kept separate. This is someone who will have to think on everyone's behalf, for this is necessary even when the others—again without intending to sound boastful—also make the effort to use their heads intelligently in anthroposophical matters. What is needed is someone who, so to speak, does not knock heads together but does hold them together. This is an individual who many will feel still needs to be tried and tested, but I believe that he will master every trial. This will be our dear Dr Guenther Wachsmuth who in everything he is obliged to do for us here has already shown his mastery of a good many trials which have made it obvious that he is capable of working with others in a most harmonious manner. As time goes on we shall find ourselves much satisfied with him. I hope, then, that you will agree to the appointment of Dr Guenther Wachsmuth, not as the cashier—which he does not want to be—but as the secretary and treasurer. (Applause) The Vorstand must be kept small, and so my list is now exhausted, my dear friends. And the time allotted for our morning meeting has also run out. I just want to call once more on all our efforts to bring into this gathering above all the appropriate mood of soul, more and yet more mood of soul. Out of this anthroposophical mood of soul will arise what we need for the next few days. And if we have it for the next few days we shall also have it for the future times we are about to enter for the Anthroposophical Society. I have appealed to your hearts; I have appealed to the wisdom in you which your hearts can fill with glowing warmth and enthusiasm. May we sustain this glowing warmth and this enthusiasm throughout the coming meetings and thus achieve something truly fruitful over the next few days. There are two more announcements to be made: This afternoon there will be two performances of one of the Christmas Plays, the Paradise Play. The first will take place at 4.30. Those who cannot find a seat then will be able to see it at 6 o'clock. Everybody will have a chance to see this play today. Our next meeting is at 8 o'clock this evening when my first lecture on world history in the light of Anthroposophy will take place. Tomorrow, Tuesday, at 10 o'clock we shall gather here for the laying of the Foundation Stone of the Anthroposophical Society, and, following straight on from that will be the Foundation Meeting of the Anthroposophical Society. The meeting of General Secretaries and delegates planned for this afternoon will not take place because it will be better to hold it after the Foundation Meeting has taken place. It will be tomorrow at 2.30 in the Glass House lower down the hill, in the Architects' Office. That will be the meeting of the Vorstand, the General Secretaries and those who are their secretaries. If Herr Abels could now come up here, I would request you to collect your meal tickets from him. To avoid chaos down at the canteen there will be different sittings and we hope that everything will proceed in an orderly fashion.

|

| 260. The Christmas Conference : The Laying the Foundation Stone for the Anthroposophical Society

25 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| In our hearts, in our thoughts and in our will let us bring to life that original consecrated night of Christmas which took place two thousand years ago, so that it may help us when we carry forth into the world what shines towards us through the light of thought of that dodecahedral Foundation Stone of love which is shaped in accordance with the universe and has been laid into the human realm. So let the feelings of our heart be turned back towards the original consecrated night of Christmas in ancient Palestine. At the turning of the time The Spirit-Light of the world Entered the stream of earthly being. |

| This turning of our feelings back to the original consecrated night of Christmas can give us the strength for the warming of our hearts and the enlightening of our heads which we need if we are to practise rightly, working anthroposophically, what can arise from the knowledge of the threefold human being coming to harmony in unity. |

| 260. The Christmas Conference : The Laying the Foundation Stone for the Anthroposophical Society

25 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

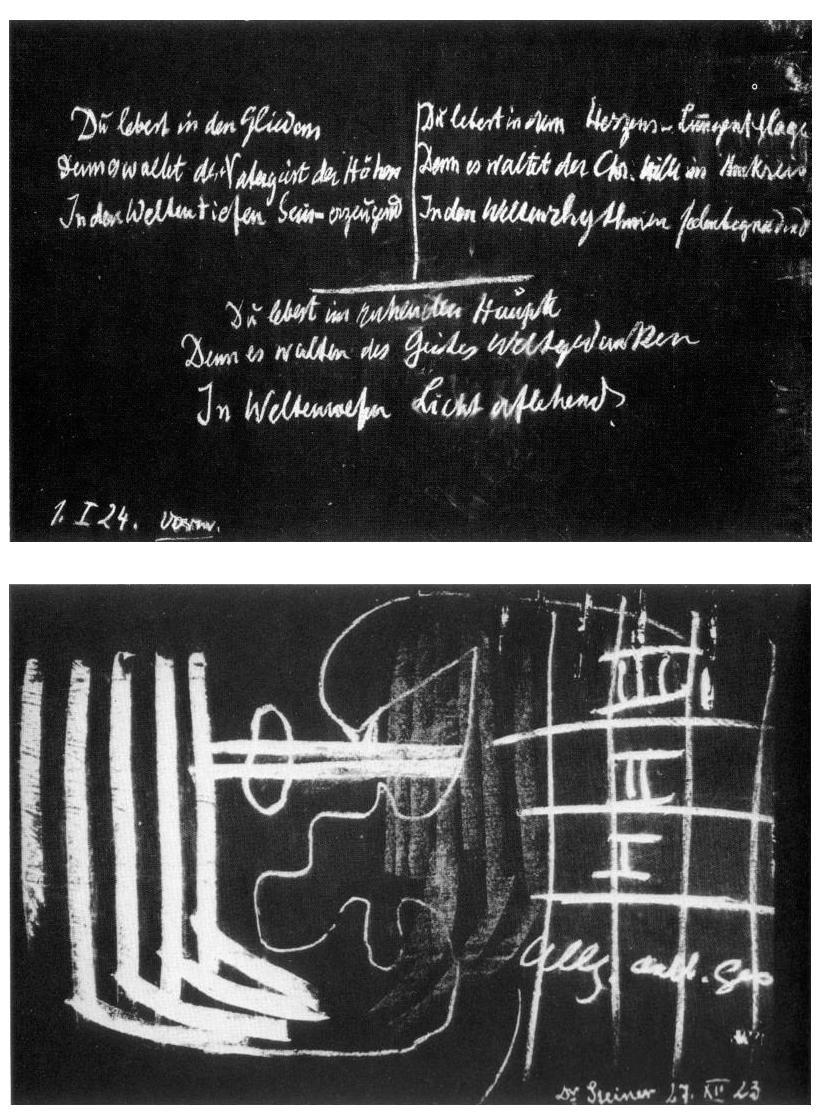

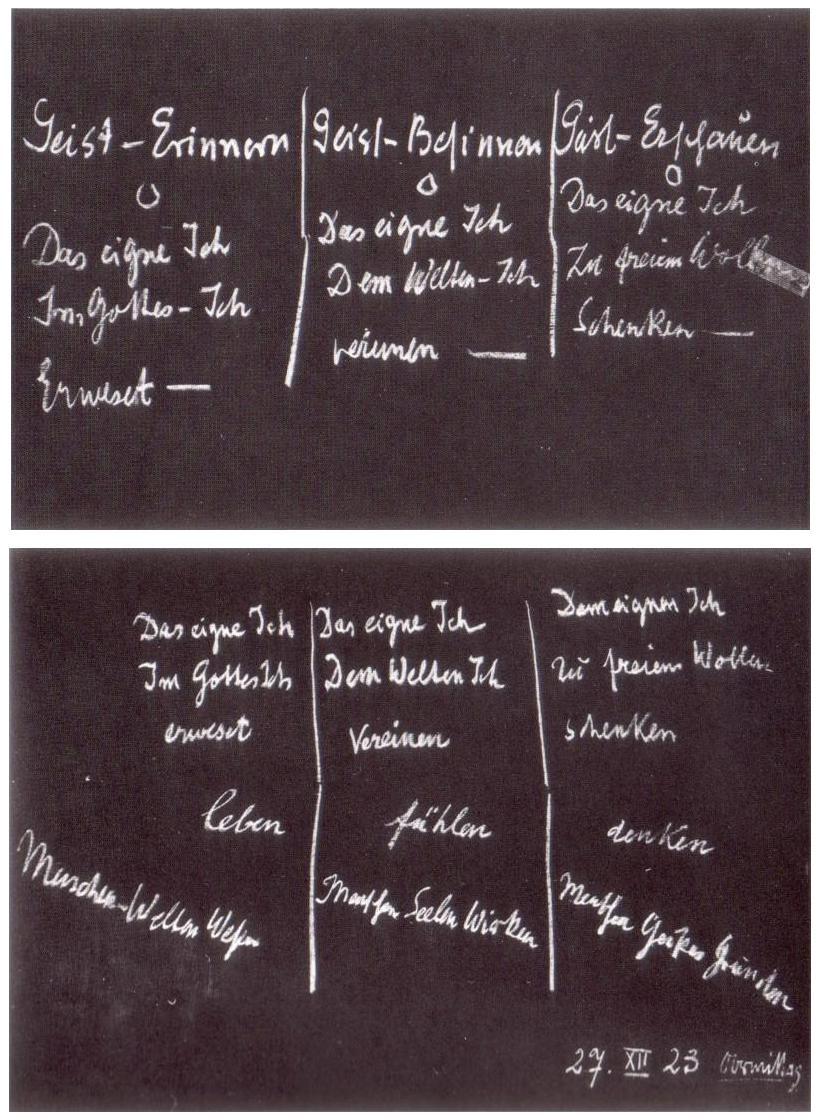

DR STEINER greets those present with the words: My dear friends! Let the first words to resound through this room today be those which sum up the essence of what may stand before your souls as the most important findings of recent years.A Later there will be more to be said about these words which are, as they stand, a summary. But first let our ears be touched by them, so that out of the signs of the present time we may renew, in keeping with our way of thinking, the ancient word of the Mysteries: ‘Know thyself.’

My dear friends! Today when I look back specifically to what it was possible to bring from the spiritual worlds while the terrible storms of war were surging across the earth, I find it all expressed as though in a paradigm in the trio of verses your ears have just heard.B For decades it has been possible to perceive this threefoldness of man which enables him in the wholeness of his being of spirit, soul and body to revive for himself once more in a new form the call ‘Know thyself’. For decades it has been possible to perceive this threefoldness. But only in the last decade have I myself been able to bring it to full maturity while the storms of war were raging.38 I sought to indicate how man lives in the physical realm in his system of metabolism and limbs, in his system of heart and rhythm, in his system of thinking and perceiving with his head. Yesterday I indicated how this threefoldness can be rightly taken up when our hearts are enlivened through and through by Anthroposophia. We may be sure that if man learns to know in his feeling and in his will what he is actually doing when, as the spirits of the universe enliven him, he lets his limbs place him in the world of space, that then—not in a suffering, passive grasping of the universe but in an active grasping of the world in which he fulfils his duties, his tasks, his mission on the earth—that then in this active grasping of the world he will know the being of all-wielding love of man and universe which is one member of the all-world-being. We may be sure that if man understands the miraculous mystery holding sway between lung and heart—expressing inwardly the beat of universal rhythms working across millennia, across the aeons of time to ensoul him with the universe through the rhythms of pulse and blood—we may hope that, grasping this in wisdom with a heart that has become a sense organ, man can experience the divinely given universal images as out of themselves they actively reveal the cosmos. Just as in active movement we grasp the all-wielding love of worlds, so shall we grasp the archetypal images of world existence when we sense in ourselves the mysterious interplay between universal rhythm and heart rhythm, and through this the human rhythm that takes place mysteriously in soul and spirit realms in the interplay between lung and heart. And when, in feeling, the human being rightly perceives what is revealed in the system of his head, which is at rest on his shoulders even when he walks along, then, feeling himself within the system of his head and pouring warmth of heart into this system of his head, he will experience the ruling, working, weaving thoughts of the universe within his own being. Thus he becomes the threefoldness of all existence: universal love reigning in human love; universal Imagination reigning in the forms of the human organism; universal thoughts reigning mysteriously below the surface in human thoughts. He will grasp this threefoldness and he will recognize himself as an individually free human being within the reigning work of the gods in the cosmos, as a cosmic human being, an individual human being within the cosmic human being, working for the future of the universe as an individual human being within the cosmic human being. Out of the signs of the present time he will re-enliven the ancient words: ‘Know thou thyself!’ The Greeks were still permitted to omit the final word, since for them the human self was not yet as abstract as it is for us now that it has become concentrated in the abstract ego-point or at most in thinking, feeling and willing. For them human nature comprised the totality of spirit, soul and body. Thus the ancient Greeks were permitted to believe that they spoke of the total human being, spirit, soul and body, when they let resound the ancient word of the Sun, the word of Apollo: ‘Know thou thyself!’ Today, re-enlivening these words in the right way out of the signs of our times, we have to say: Soul of man, know thou thyself in the weaving existence of spirit, soul and body. When we say this, we have understood what lies at the foundation of all aspects of the being of man. In the substance of the universe there works and is and lives the spirit which streams from the heights and reveals itself in the human head; the force of Christ working in the circumference, weaving in the air, encircling the earth, works and lives in the system of our breath; and from the inmost depths of the earth rise up the forces which work in our limbs. When now, at this moment, we unite these three forces, the forces of the heights, the forces of the circumference, the forces of the depths, in a substance that gives form, then in the understanding of our soul we can bring face to face the universal dodecahedron with the human dodecahedron. Out of these three forces: out of the spirit of the heights, out of the force of Christ in the circumference, out of the working of the Father, the creative activity of the Father that streams out of the depths, let us at this moment give form in our souls to the dodecahedral Foundation Stone which we lower into the soil of our souls so that it may remain there a powerful sign in the strong foundations of our soul existence and so that in the future working of the Anthroposophical Society we may stand on this firm Foundation Stone. Let us ever remain aware of this Foundation Stone for the Anthroposophical Society, formed today. In all that we shall do, in the outer world and here, to further, to develop and to fully unfold the Anthroposophical Society, let us preserve the remembrance of the Foundation Stone which we have today lowered into the soil of our hearts. Let us seek in the threefold being of man, which teaches us love, which teaches us the universal Imagination, which teaches us the universal thoughts; let us seek, in this threefold being, the substance of universal love which we lay as the foundation, let us seek in this threefold being the archetype of the Imagination according to which we shape the universal love within our hearts, let us seek the power of thoughts from the heights which enable us to let shine forth in fitting manner this dodecahedral Imagination which has received its form through love! Then shall we carry away with us from here what we need. Then shall the Foundation Stone shine forth before the eyes of our soul, that Foundation Stone which has received its substance from universal love and human love, its picture image, its form, from universal Imagination and human Imagination, and its brilliant radiance from universal thoughts and human thoughts, its brilliant radiance which whenever we recollect this moment can shine towards us with warm light, with light that spurs on our deeds, our thinking, our feeling and our willing. The proper soil into which we must lower the Foundation Stone of today, the proper soil consists of our hearts in their harmonious collaboration, in their good, love-filled desire to bear together the will of Anthroposophy through the world. This will cast its light on us like a reminder of the light of thought that can ever shine towards us from the dodecahedral Stone of love which today we will lower into our hearts. Dear friends, let us take this deeply into our souls. With it let us warm our souls, and with it let us enlighten our souls. Let us cherish this warmth of soul and this light of soul which out of good will we have planted in our hearts today. We plant it, my dear friends, at a moment when human memory that truly understands the universe looks back to the point in human evolution, at the turning point of time, when out of the darkness of night and out of the darkness of human moral feeling, shooting like light from heaven, was born the divine being who had become the Christ, the spirit being who had entered into humankind. We can best bring strength to that warmth of soul and that light of soul which we need, if we enliven them with the warmth and the light that shone forth at the turning point of time as the Light of Christ in the darkness of the universe. In our hearts, in our thoughts and in our will let us bring to life that original consecrated night of Christmas which took place two thousand years ago, so that it may help us when we carry forth into the world what shines towards us through the light of thought of that dodecahedral Foundation Stone of love which is shaped in accordance with the universe and has been laid into the human realm. So let the feelings of our heart be turned back towards the original consecrated night of Christmas in ancient Palestine.

This turning of our feelings back to the original consecrated night of Christmas can give us the strength for the warming of our hearts and the enlightening of our heads which we need if we are to practise rightly, working anthroposophically, what can arise from the knowledge of the threefold human being coming to harmony in unity. So let us once more gather before our souls all that follows from a true understanding of the words ‘Know thou thyself in spirit, soul and body’. Let us gather it as it works in the cosmos so that to our Stone, which we have now laid in the soil of our hearts, there may speak from everywhere into human existence and into human life and into human work everything that the universe has to say to this human existence and to this human life and to this human work.

My dear friends, hear it as it resounds in your own hearts! Then will you found here a true community of human beings for Anthroposophia; and then will you carry the spirit that rules in the shining light of thoughts around the dodecahedral Stone of love out into the world wherever it should give of its light and of its warmth for the progress of human souls, for the progress of the universe.

|

| 260. The Christmas Conference : The Foundation Meeting of the General Anthroposophical Society

25 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| 260. The Christmas Conference : The Foundation Meeting of the General Anthroposophical Society

25 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Dr. Steiner greets those present with the words: My dear friends! Allow me forthwith to open the Foundation Meeting of the Anthroposophical Society. My first task is to announce the names of the General Secretaries who will speak on behalf of the national Societies:

Secondly I have to read to you a telegram which has arrived: ‘Please convey to the gathering our cordial greetings and best wishes for a good outcome, in the name of Sweden's anthroposophists.’ Before coming to the first point on the agenda I wish to ask whether in accordance with the rules of procedure anyone wishes to comment on the agenda? No-one. Then let us take the first point on the agenda. I call on Herr Steffen, who will also be speaking as the General Secretary of the Society in Switzerland, within whose boundaries we are guests here. Albert Steffen speaks: He concludes by reading a resolution of the Swiss delegates: The delegates of the Swiss branches have decided to announce publicly today, on the occasion of the Foundation Meeting, the following resolution: ‘Today, on the occasion of the Foundation Meeting of the General Anthroposophical World Society in Dornach, the Anthroposophical Society in Switzerland wishes to express its gratitude and enthusiasm for the fact that the Goetheanum, which serves the cultural life of all mankind, is to be built once again in Switzerland. The Swiss Society sees in this both good fortune and great honour for its country. It wishes to verify that it will do everything in its power to ensure that the inexhaustible abundance of spiritual impulses given to the world through the works of Rudolf Steiner can continue to flow out from here. In collaboration with the other national Societies it wants to hope that the pure and beneficial source may become accessible to all human beings who seek it.’ Dr. Steiner: My dear friends, in the interest of a proper continuation of the Meeting it seems to me sensible to postpone the discussion on announcements such as that we have just heard to a time which will arise naturally out of the proceedings. For the second point on the agenda I now wish to call for the reports to be given by the various Secretaries of the various national Societies. If anyone does not agree with this arrangement of the agenda, please raise your hand. It seems that no-one disagrees, so let us continue with the agenda. Will the different General Secretaries please come to the platform to speak to our friends. I first call on the General Secretary for the United States of America, Mr Monges, to speak. Mr Monges gives his report. Dr. Steiner: I would now like to call on the General Secretary for Belgium, Madame Muntz, to speak. Madame Muntz expresses her thanks for this honour, declares herself in agreement with all the statements that have been made and wishes the Meeting all the best. Dr. Steiner: I now call on the General Secretary for Denmark, Herr Hohlenberg, to speak. Herr Hohlenberg reports. Dr. Steiner: I now call on the representative of the Council in Germany, Dr Unger, to speak. Dr. Unger reports on the work of the German national Society. He concludes with words which have been recorded in the short-hand report: At present we require in some aspects a rather comprehensive structure to accommodate this Society. This will have to be brought into full conformity with the Statutes presented here by Dr. Steiner for the founding of the General Society. We declare that the Anthroposophical Society in Germany will incorporate every point of these Statutes into its own Statutes and that these Statutes as a whole will be given precedence over the Statutes or Rules of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany. In addition I have also been especially called upon to express deep gratitude to Dr. Steiner for taking on the heavy obligations arising out of the founding of the General Anthroposophical Society. Out of all the impressions gained from this Conference, the question will have to be asked whether every aspect of the work done in a large Society such as that in Germany can participate in and wants to participate in what is wanted by Dornach. Ever since Dr. Steiner took up residence in Dornach, ever since there has been work going on in Dornach, it has always gone without saying that what took place in Dornach was seen as the central point of all our work. Whatever else needs to be said about the work of the Society in Germany will be better brought forward during the further course of our gatherings. Let me just say, however, that in recent months we have begun a very intensive public programme. Hundreds of lectures of all kinds, but particularly also those arising out of a purely anthroposophical intention, have been given, especially in the southwestern part of Germany, even in the smallest places. All those who have participated, and there are many, agree without reservation that even in the smallest places there is a genuine interest in Anthroposophy, that everywhere hearts are waiting for Anthroposophy, and that wherever it is clearly and openly stated that the speaker stands on the soil of the spiritual research given to the world by Dr. Steiner it is really so that people feel: I am reminded that I have a soul and that this soul is beginning to be aware of itself once more. This is the case in all human souls, even those found in the smallest places, so we may look with confidence towards continuing our work in future. Dr. Steiner: I now call on the representative of the Free Anthroposophical Society in Germany, Dr Büchenbacher, to speak. Dr Büchenbacher reports and concludes with the words: I would like to express our feeling of deepest gratitude to Dr. Steiner for taking upon himself the leadership of the Anthroposophical Society. This gives us the will and the courage to work with what strength we have on the general stream of forces of the Anthroposophical Society. We express our profoundest thanks to him for having done this deed. And we request that the Free Anthroposophical Society for its part may be permitted to work according to its capacity towards the fulfilment of the tasks which Dr. Steiner has set it. Dr. Steiner: May I now call on the General Secretary of the English Anthroposophical Society, Mr Collison, to speak. Mr Collison reports. Dr. Steiner: I now call on the General Secretary of the Anthroposophical Society in Finland, Herr Donner, to speak. Herr Donner reports. Dr. Steiner: I now call on the General Secretary of the Anthroposophical Society in France, Mademoiselle Sauerwein, to speak. Mademoiselle Sauerwein reports. Dr. Steiner: I now call on the Dutch General Secretary of the Anthroposophical Society, Dr Zeylmans van Emmichoven, to speak. Dr Zeylmans van Emmichoven reports. Dr. Steiner: May I ask you to remain in your seats for a few more moments, dear friends. First of all, even during this Conference forgetfulness has led to the accumulation of a number of items of lost property. These have been gathered together and may be collected by the losers from Herr Kellermüller on their way out. Secondly, the programme for the remainder of today will be as follows: At 2.30 there will be a meeting of the Vorstand with the General Secretaries, and any secretaries they may have brought with them, down in the Glass House, in the Architects' Office. This meeting will be for the Vorstand, the General Secretaries, and possibly their secretaries, only. At 4.30 there will be a performance of the Nativity Play here. Because of a eurythmy rehearsal my evening lecture will begin at 8.30. I now adjourn today's meeting of members till tomorrow morning at 10 o'clock. I shall then have the pleasure of calling on the representative of Honolulu, Madame Ferreri, to speak, and representatives of other groups who did not speak today. The meeting is now adjourned till tomorrow morning at 10 o'clock. |

| 260. The Christmas Conference : Meeting of the Vorstand and the General Secretaries

25 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Dr Wachsmuth informs the meeting that the South American Society had written a letter just before Christmas, having heard about the new decisions. He reads a statement from them. Herr Leinhas: I have had a similar letter. |

| 260. The Christmas Conference : Meeting of the Vorstand and the General Secretaries

25 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|