| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: Invitation to All Societies and Groups to the International Delegates' Conference in Dornach

22 Jun 1923, Dornach |

|---|

| Since there is no longer time to convene a general assembly of the German Anthroposophical Society to discuss the issues to be addressed at the delegates' meeting in Dornach, we propose that those members of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany who are able to come to Dornach meet with the board of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany for a preliminary discussion on July 21 at the Glass Studio. 1 This will give the Executive Council of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany an opportunity to hear the wishes and suggestions of the members before the delegates' meeting, to discuss them and thus to represent the Anthroposophical Society in Germany in a unified way. With best regards, The Board of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany i. A.: Dr.-Ing. Carl Unger, Dr. Walter Johannes Stein 1. |

| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: Invitation to All Societies and Groups to the International Delegates' Conference in Dornach

22 Jun 1923, Dornach |

|---|

The above letter of invitation came into our hands on June 25; we will distribute it as quickly as possible among all working groups of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany. We very much hope that quite a few of our members will find the opportunity to be present at this assembly of delegates. Since there is no longer time to convene a general assembly of the German Anthroposophical Society to discuss the issues to be addressed at the delegates' meeting in Dornach, we propose that those members of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany who are able to come to Dornach meet with the board of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany for a preliminary discussion on July 21 at the Glass Studio. 1 This will give the Executive Council of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany an opportunity to hear the wishes and suggestions of the members before the delegates' meeting, to discuss them and thus to represent the Anthroposophical Society in Germany in a unified way. With best regards,

|

| 260. The Christmas Conference : Continuation of the Foundation Meeting

27 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The third thing to consider will be a matter raised in a meeting of delegates of the Anthroposophical Society in Switzerland, namely how to organize the relationship between the members of the Anthroposophical Society who live here close to the Goetheanum either permanently or on a temporary basis on the one hand and the members of the Swiss Anthroposophical Society on the other. |

| For things to appear in a more orderly fashion in the future, it will be necessary for the Swiss Anthroposophical Society to form itself with a Council and perhaps also a General Secretary like those of the other national Anthroposophical Societies. |

| While the Statutes were being printed I wondered whether a note might be added to this point: ‘The General Anthroposophical Society founded here was preceded by the Anthroposophical Society founded in 1912.’ Something like that. |

| 260. The Christmas Conference : Continuation of the Foundation Meeting

27 Dec 1923, Dornach Translated by Johanna Collis, Michael Wilson Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

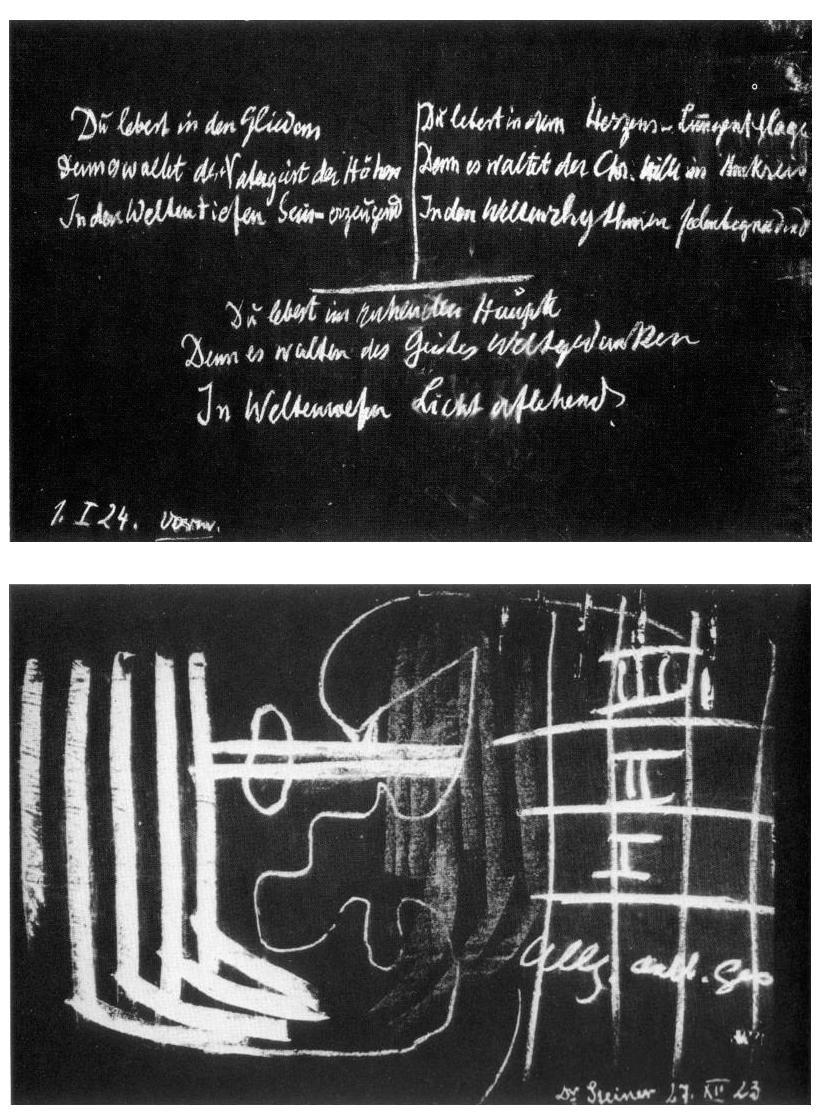

DR STEINER: My dear friends! Once more let us fill our hearts with the words which out of the signs of the times are to give us in the right way the self knowledge we need:

Once more out of these cosmic verses let us write down before our souls a rhythm so that we may gradually press forward spiritually to their structure. From the first verse we take the words:

And from the second verse, which contains a second soul process, we take:

And from the third verse we take:

With these words, to form the corresponding rhythm, we now unite those words which always sound with them, having an inner soul connection with these that I have already written on the blackboard:

You will find, my dear friends, that if you pay attention to the inner rhythms that lie in these verses, if you then present these inner rhythms to your soul and perform a suitable meditation within yourself, allowing your thoughts to come to rest upon them, then these sayings can be felt to be the speaking of cosmic secrets in so far as these cosmic secrets are resurrected in the human soul as human self knowledge. Now, dear friends, let us prepare to have—if you will pardon the ugly expression—a general debate about the Statutes. To start with let me draw your attention to what kind of points come into question for this general debate. Later—if you will pardon an even uglier expression—we shall have a kind of detailed debate on special concerns about the individual Paragraphs. The first thing to be considered would be the fact that in future the Vorstand-committee situated in Dornach is to be a true Vorstand which takes into account the central initiative necessary in every single case with respect to one thing or another. It will be less a matter of knowing that there is a Vorstand in such and such a place to which it is possible to turn in one matter or another—though this too is possible and necessary, of course. Rather it will be a matter of the Vorstand developing the capacity to have active initiatives of its own in the affairs of the Anthroposophical Movement, giving suggestions which are really necessary in the sense of the final point in the last Paragraph of the Statutes: ‘The organ of the Society is Das Goetheanum, which for this purpose is provided with a Supplement containing the official communications of the Society. This enlarged edition of Das Goetheanum will be supplied to members of the Anthroposophical Society only.’ In this Supplement will be found everything the Vorstand thinks, would like to do and, on occasion, will be able to do. Thus especially through the Supplement to Das Goetheanum the Vorstand will constantly have the intention of working outwards in a living way. But as you know, for blood to circulate there have to be not only centrifugal forces but also centripetal forces that work inwards. Therefore arrangements will have to be made so that a number of members unite themselves closely in their soul with the Vorstand in everything that might concern not only the Anthroposophical Society in the narrower sense but also in the whole cultural life of the present day in relation to the working of the Anthroposophical Society. A number of members will be closely linked in their soul with the Vorstand in order to communicate back all that goes on outside in the world. By this means we shall achieve an entirely free constitution of the Anthroposophical Society, a constitution built on a free interchange. Then stimulus and suggestion will come from every direction. And these suggestions will bear fruit depending on the way in which things are recognized. So it will have to be arranged that there are correspondents for the Vorstand which is located in Dornach, where it works. At the present moment of the Anthroposophical Society's development it is important that we make our arrangements on the basis of reality and not of principles. There is, is there not, a difference between the two. If you base your considerations on the structure of a society and arrange its affairs in accordance with this, then you have a theoretical structure of principles. We have had plenty of this kind of thing recently, and it was absolutely no use. Indeed in many ways it caused us serious difficulties. So I want to exert every effort to make arrangements in the future that arise out of the real forces of the Society, out of the forces that exist already and have already had their effect, and of which it can be seen from their context that they can work. So it seems to me that it would be a good thing to be clear at least in spirit about the establishment of correspondents of the Vorstand, people who would take on the voluntary duty of writing to us every week about what they consider noteworthy in cultural life outside in the world and about what might be interesting for the Anthroposophical Society. A number of people, which could always of course be extended, ought to take on this obligation here and now. I for my part should like to suggest several people straight away to constitute an externally supporting Vorstand that is exactly equivalent to the central Vorstand which, as I have already said, is located here in Dornach, which means that it cannot have any members who do not live here in Dornach. In this way we would achieve a genuine circulation of blood. So I want to suggest that certain persons of the following kind—forgive me for generalizing; we can certainly discuss this further—keep in regular contact with the Vorstand on a weekly basis. The kind of person I mean is someone who has already resolved to work very actively out there in the periphery for our anthroposophical cause: Herr van Leer. Secondly I am thinking of the following people: Mr Monges, Mr Collison, Mrs Mackenzie, Herr Ingerö, Herr Zeylmans, Mademoiselle Sauerwein, Baroness de Renzis, Madame Ferreri, Fräulein Schwarz, Count Polzer, Dr Unger, Herr Leinhas, Dr Büchenbacher. I have started by naming these people because I am of the opinion that if they would commit themselves voluntarily to report in a letter every week to the editors of Das Goetheanum, not only on what is going on in the anthroposophical field but on anything that might be interesting for Anthroposophy in the cultural life of the world and indeed life in general, this would give us a good opportunity to shape this Supplement to Das Goetheanum very fruitfully. The second thing to consider in the general debate about the Statutes is the fact that the establishment of a Vorstand in the way I have suggested to you means that the Anthroposophical Society will be properly represented, so that other associations or organizations which exist for the promotion of the cause of Anthroposophy, wherever they happen to be, can refer back to this central Vorstand. The central Vorstand will have to consider its task to be solely whatever lies in the direction of fulfilling the Statutes. It will have to do everything that lies in the direction of fulfilling the Statutes. This gives it great freedom. But at the same time we shall all know what this central Vorstand represents, since from the Statutes we can gain a complete picture of what it will be doing. As a result, wherever other organizations arise, for instance the Goetheanum Bauverein, it will be possible for them to stand on realistic ground. Over the next few days there will be the task of creating a suitable relationship between the Vorstand that has come into being and the Goetheanum Bauverein.46 But today in the general debate about the Statutes we can discuss anything of this kind which might be worrying you about them. The third thing to consider will be a matter raised in a meeting of delegates of the Anthroposophical Society in Switzerland, namely how to organize the relationship between the members of the Anthroposophical Society who live here close to the Goetheanum either permanently or on a temporary basis on the one hand and the members of the Swiss Anthroposophical Society on the other. It was quite justifiably stated here the other day at a delegates' meeting of our Swiss friends47 that if people who happen to be present by coincidence, or perhaps not by coincidence but only temporarily, for a short while, interfere too much in the affairs of the Swiss Society, then the Swiss friends might feel pressured in their meetings. We need to ensure that the Goetheanum branch—though for obvious reasons it should and must be a part of the Swiss Anthroposophical Society—is given a position which prevents it, even if it has non-Swiss members, from ever becoming an instrument for persuasion or for creating a majority. This is what was particularly bothering the Swiss members at their delegates' meeting recently. This situation has become somewhat awkward for the following reasons: The suggestion had been made by me to found national Societies on the basis of which the General Anthroposophical Society would be founded here at Christmas. These national Societies have indeed come into being almost without exception in every country where there are anthroposophists. At all these anthroposophical foundation meetings it was said in one way or another that a national Society would be founded like the one already in existence in Switzerland. So national Societies were founded everywhere along the lines of the Swiss Anthroposophical Society. However, it is important to base whatever happens on clear statements. If this had been done there would have been no misunderstanding which led to people saying that since national Societies were being founded everywhere a Swiss national Society ought to be formed too. After all, it was the Swiss Society on which the others were modelled. However, the situation was that the Swiss Society did not have a proper Council, since its Council was made up of the chairmen of the different branches. This therefore remains an elastic but rather indeterminate body. For things to appear in a more orderly fashion in the future, it will be necessary for the Swiss Anthroposophical Society to form itself with a Council and perhaps also a General Secretary like those of the other national Anthroposophical Societies. Then it will be possible to regularize the relationship with the Goetheanum branch. This is merely a suggestion. But in connection with it I want to say something else. The whole way in which I consider that the central Vorstand, working here at the Goetheanum, should carry out its duties means that of necessity there is an incompatibility between the offices of this Vorstand and any other offices of the Anthroposophical Society. Thus a member of the Vorstand I have suggested to you here ought not to occupy any other position within the Anthroposophical Society. Indeed, dear friends, proper work cannot be done when offices are heaped one on top of another. Above all else let us in future avoid piling offices one on top of the other. So it will be necessary for our dear Swiss friends to concern themselves with choosing a General Secretary, since Herr Steffen, as the representative of the Swiss, whose guests we are in a certain way as a worldwide Society, will in future be taking up the function of Vice-president of the central Society. You were justifiably immensely pleased to agree with this. I do not mean to say that this is incompatible with any other offices but only with other offices within the Anthroposophical Society. Another thing I want to say is that I intend to carry out point 5 by arranging the School of Spiritual Science in Dornach in Sections as follows. These will be different from the Classes.48 The Classes will encompass all the Sections. Let me make a drawing similar to that made by Dr Wachsmuth; not the same, but I hope it encompasses the whole earth in the same way. The Classes will be like this: General Anthroposophical Society, First Class, Second Class, Third Class of the School of Spiritual Science. The Sections will reach from top to bottom, so that within each Section it will be possible to be a member of whichever Class has been attained. The Sections I would like to found are: First of all a General Anthroposophical Section, which will to start with be combined with the Pedagogical Section. I myself should like to take this on in addition to the overall leadership of the School of Spiritual Science. Then I want to arrange the School in such a way that each Section has a Section Leader who is responsible for it; I believe these must be people residing here. One Section will encompass what in France is called ‘belles-lettres.’ Another will encompass the spoken arts and music together with eurythmy. A third Section will encompass the plastic arts. A fourth Section is to encompass medicine. A fifth is to encompass mathematics and astronomy. And the last, for the moment, is to be for the natural sciences. So suitable representatives will be found here for these Sections which are those which for the time being can responsibly be included within the general anthroposophical sphere which I myself shall lead. The Section Leaders must, of course, be resident here. These, then, are the main points on which I would like the general debate to be based. I now ask whether the applications to speak, already handed in, refer to these points. Applications to speak have been handed in by Herr Leinhas, Dr Kolisko, Dr Stein, Dr Palmer, Herr Werbeck, Miss Cross, Mademoiselle Rihouët, Frau Hart-Nibbrig, Herr de Haan, Herr Stibbe, Herr Tymstra, Herr Zagwijn, Frau Ljungquist. On behalf of Switzerland, the working committee. On behalf of Czechoslovakia, Dr Krkavec, Herr Pollak, Dr Reichel, Frau Freund. Do these speakers wish to refer to the debate which is about to begin? (From various quarters the answer is: No!) DR STEINER: Then may I ask those wishing to speak to raise their hands and to come up here to the platform. Who would like to speak to the general debate? DR ZEYLMANS: Ladies and gentlemen, I merely want to say that I shall be very happy to take on the task allotted to me by Dr Steiner and shall endeavour to send news about the work in Holland to Dornach each week. DR STEINER: Perhaps we can settle this matter by asking all those I have so far mentioned—the list is not necessarily complete—to be so good as to raise their hands. (All those mentioned do so.) Is there anyone who does not want to take on this task? Please raise your hand. (Nobody does so.) You see what a good example has been set in dealing with this first point. All those requested to do so have declared themselves prepared to send a report each week to the editors of Das Goetheanum. This will certainly amount to quite a task for Herr Steffen, but it has to be done, for of course the reports must be read here once they arrive. Does anyone else wish to speak to the general debate? If not, may I now ask those friends who agree in principle with the Statutes as Statutes of the General Anthroposophical Society to raise their hands. In the second reading we shall discuss each Paragraph separately. But will those who agree in principle please raise their hands. (They do.) Will those who do not wish to accept these Statutes in principle please raise their hands. (Nobody does.) The draft Statutes have thus been accepted in their first reading. (Lively applause.) We now come to the detailed debate, the second reading, and I shall ask Dr Wachsmuth to read the Statutes Paragraph by Paragraph for this debate in detail. Dr Wachsmuth reads Paragraph 1 of the Statutes:

DR STEINER: Would anyone now like to speak to the content or style and phrasing of this first Paragraph of the Statutes? Dear friends, you have been in possession of the Statutes for more than three days. I am quite sure that you have thought deeply about them. HERR KAISER: With reference to the expression ‘the life of the soul’ I wondered whether people might not ask: Why not life as a whole? This is one of the things I wanted to say. Perhaps an expression that is more general than ‘of the soul’ could be used. DR STEINER: Would you like to make a suggestion to help us understand better what you mean? HERR KAISER: I have only just noticed this expression. I shall have to rely on your help as I can't think of anything better at the moment. I just wanted to point out that the general public might be offended by the idea that we seem to want to go and hide away with our soul in a vague kind of way. DR STEINER: Paragraph 1 is concerned with the following: Its phrasing is such that it points to a certain nurturing of the life of the soul without saying in detail what the content of the activity of the Anthroposophical Society is to be. I believe that especially at the present time it is of paramount importance to point out that in the Anthroposophical Society the life of the soul is of central concern. That is why it says that the Anthroposophical Society is to be an association of people who cultivate the life of the soul in this way. We can talk about the other words later. The other things it does are stated in the subsequent points. We shall speak more about this. This is the first Paragraph. Even the first Paragraph should say something as concrete as possible. If I am to ask: What is a writer? I shall have to say: A writer is a person who uses language in order to express his thoughts, or something similar. This does not mean to say that this encompasses the whole of his activity as a human being; it merely points out what he is with regard to being a writer. Similarly I think that the first point indicates that the Anthroposophical Society, among all kinds of other things which are expressed in the subsequent points, also cultivates the life of the soul in the individual and in human society in such a way that this cultivation is based on a true knowledge of the spiritual world. I think perhaps Herr Kaiser meant that this point ought to include a kind of survey of all the subsequent points. But this is not how we want to do it. We want to remain concrete all the time. The only thing to be stated in the first point is the manner in which the life of the soul is to be cultivated. After that is stated what else we do and do not want to do. Taken in this way, I don't think there is anything objectionable in this Paragraph. Or is there? If anyone has a better suggestion I am quite prepared to replace ‘of the soul’ with something else. But as you see, Herr Kaiser did think briefly about it and did not come up with any other expression. I have been thinking about it for quite a long time, several weeks, and have also not found any other expression for this Paragraph. It will indeed be very difficult to find a different expression to indicate the general activity of the Anthroposophical Society. For the life of the soul does, after all, encompass everything. On the one hand in practical life we want to cultivate the life of the soul in such a way that the human being can learn to master life at the practical level. On the other hand in scientific life we want to conduct science in such a way that the human soul finds it satisfying. Understood rightly, the expression ‘the life of the soul’ really does express something universal. Does anyone else want to speak to Paragraph 1? If not, I shall put this point 1 of the Statutes to the vote. Please will those who are in favour of adopting this point raise their hands. This vote refers to this one point only, so you are not committing yourselves to anything else in the Statutes. (The vote is taken.) If anyone objects to Paragraph 1, please raise your hand. (Nobody does.) Our point 1 is accepted. Please read point 2 of the Statutes. Dr Wachsmuth reads Paragraph 2 of the Statutes:

DR STEINER: The first purpose of this Paragraph is to express what it is that unites the individual members of the Anthroposophical Society. As I said in a general discussion a few days ago, we want to build on facts, not on ideas and principles. The first fact to be considered is most gratifying, and that is that eight hundred people are gathered together here in Dornach who can make a declaration. They are not going to make a declaration of ideas and principles to which they intend to adhere. They are going to declare: At the Goetheanum in Dornach there exists a certain fundamental conviction. This fundamental conviction, which is expressed in this point, is essentially shared by all of us and we are therefore the nucleus of the Anthroposophical Society. Today we are not dealing with principles but with human beings. You see these people sitting here in front of you who first entertained this conviction; they are those who have been working out of this conviction for quite some time at the Goetheanum. You have come in order to found the Anthroposophical Society. You declare in the Statutes your agreement with what is being done at the Goetheanum. Thus the Society is formed, humanly formed. Human beings are joining other human beings. Human beings are not declaring their agreement with Paragraphs which can be interpreted in this way or in that way, and so on. Would anyone like to speak to Paragraph 2? DR UNGER: My dear friends! Considering the very thing that has brought all these people together here we must see this point 2 as something which is expressed as a whole by all those members of the Anthroposophical Society gathered here. Acknowledgement of the very thing which has brought us together is what is important. That is why I wonder whether we might not find a stronger way of expressing the part which says ‘are convinced that there exists in our time a genuine science of the spiritual world ... ’ As it stands it sounds rather as though spiritual science just happens to exist, whereas what every one of us here knows, and what we have all committed ourselves to carry out into the world, has in fact been built up over many years. Would it not be possible to formulate something which expresses the years of work in wide-reaching circles? I am quite aware that Dr Steiner does not wish to see his name mentioned here because this could give a false impression. We ought to be capable of expressing through the Society that this science exists, given by the spiritual world, and that it has been put before all mankind in an extensive literature. This ‘having been put before all mankind’ ought to be more strongly expressed as the thing that unites the Society. DR STEINER: Dear friends, you can imagine that the formulation of this sentence was quite a headache for me too. Or don't you believe me? Perhaps Dr Unger could make a suggestion. DR UNGER suggests: ‘represented by a body of literature that has been presented to all mankind over many years.’ This could simply be added to the sentence as it stands. DR STEINER: Would your suggestion be met by the following formulation: ‘are convinced that there exists in our time a genuine science of the spiritual world elaborated for years past, and in important particulars already published?’ DR UNGER: Yes. DR STEINER: So we shall put ‘elaborated for years past, and in important particulars already published ...’ Does anyone else wish to speak? Dr Schmeidel wishes to put ‘for decades past’ instead of ‘for years past’. DR STEINER: Many people would be able to point out that actually two decades have passed since the appearance of The Philosophy of Freedom.49 I do not think there is any need to make the formulation all that strong. If we are really to add anything more in this direction then I would suggest not ‘or decades past’ but ‘for many years past’. Does anyone else wish to speak? DR PEIPERS: I do not see why Dr Steiner's name should not be mentioned at this point. I should like to make an alternative suggestion: ‘in the spiritual science founded by Dr. Steiner.’ DR STEINER: This is impossible, my dear friends. What has been done here must have the best possible form and it must be possible for us to stand for what we say. It would not do for the world to discover that the draft for these Statutes was written by me and then to find my name appearing here in full. Such a thing would provide the opportunity for the greatest possible misunderstandings and convenient points for attack. I think it is quite sufficient to leave this sentence as general as it is: ‘elaborated for many years past, and in important particulars already published ...’ There is no doubt at all that all these proceedings will become public knowledge and therefore everything must be correct, inwardly as well. Would anyone else like to speak? HERR VAN LEER: The Goetheanum is mentioned here; but we have no Goetheanum. DR STEINER: We are not of the opinion that we have no Goetheanum. My dear Herr van Leer, we are of the opinion that we have no building, but that as soon as possible we shall have one. We are of the opinion that the Goetheanum continues to exist. For this very reason, and also out of the deep needs of our heart, it was necessary last year, while the flames were still burning, to continue with the work here on the very next day, without, as Herr Steffen said, having slept. For we had to prove to the world that we stand here as a Goetheanum in the soul, as a Goetheanum of soul, which of course must receive an external building as soon as possible. HERR VAN LEER: But in the outside world, or in twenty years' time, it will be said: In the year 1923 there was no Goetheanum in Dornach. DR STEINER: I believe we really cannot speak like this. We can indeed say: The building remained in the soul. Is it not important, dear Herr van Leer, to make the point as strongly as possible that here, as everywhere else, we place spiritual things in the foreground? And that what we see with our physical eyes therefore does not prevent us from saying ‘at the Goetheanum’? The Goetheanum does stand before our spiritual eyes! HERR VAN LEER: Yes indeed. DR STEINER: Does anyone else wish to speak to Paragraph 2? HERR LEINHAS: I only want to ask whether it is advisable to leave in the words ‘in important particulars already published’. Newspapers publish the fact that we do, actually, have some secret literature such as those cycles which have not yet been published. Keeping these things secret will now be made impossible by the Statutes. Is it right to indicate at this point the literature which has so far not been published? DR STEINER: Actually, this is not even what is meant. All that is meant is that there are also other truths which are not included in the lecture cycles, that is they have never yet been made public, not even in the cycles. I think we can remedy this by saying: ‘elaborated for years past and in important particulars already published’ or ‘also already published.’ This should take account of this. The ‘already’ will take account of this objection. Would anyone else like to speak to Paragraph 2 of the Statutes? HERR INGERÖ: I have a purely practical question: There are individual members here as well as representatives of groups. Obviously the groups who have sent representatives will agree to these Statutes. But otherwise will the Statutes have to be formally ratified when we get home? Will the members have to be presented with all this once again after which we would write to you to say that the Statutes have been adopted? DR STEINER: No. I have assumed that delegates from individual groups have arrived with a full mandate so that they can make valid decisions on behalf of their group. That is what is meant by this sentence. (Applause and agreement.) This was also my interpretation in regard to all the different foundation meetings of the national groups at which I was present. It will be quite sufficient if the delegates of the national groups give their agreement on the basis of the full mandate vested in them. Otherwise we should be unable to adopt the Statutes fully at this meeting. DR KOLISKO: I would like to ask about the fact that an Anthroposophical Society did exist already, known publicly as the Anthroposophical Society, yet now it appears to be an entirely new inauguration; there is no mention in Paragraph 2 of what was, up till now, the Anthroposophical Society in a way which would show that this is now an entirely new foundation. I wonder whether people might not question why there is no mention of the Anthroposophical Society which has existed for the last ten years but only of something entirely new. DR STEINER: I too have thought about this. While the Statutes were being printed I wondered whether a note might be added to this point: ‘The General Anthroposophical Society founded here was preceded by the Anthroposophical Society founded in 1912.’ Something like that. I shall suggest the full text of this note at the end of this detailed debate. For the moment let us stick to the Paragraph itself. I shall add this as a note to the Statutes. I believe very firmly that it is necessary to become strongly aware of what has become noticeable in the last few days and of what I mentioned a day or two ago when I said that we want to link up once again where we attempted to link up in the year 1912. It is necessary to become strongly aware of this, so a strong light does in fact need to be shed on the fact of the foundation of the Anthroposophical Society here and now during this present Christmas Conference. I therefore do not want to make a history lesson out of the Statutes by pointing out a historical fact, but would prefer to include this in a note, the text of which I shall suggest. I think this will be sufficient. Does anyone else wish to speak about the formulation of Paragraph 2? If not, please would those dear friends who are in favour of the adoption of this Paragraph 2 raise their hands. (They do.) Please would those who are not in favour raise their hands. Paragraph 2 is adopted herewith. Please now read Paragraph 3. Dr Wachsmuth reads Paragraph 3:

DR STEINER: Please note, dear friends, that something has been left out in the printed version. The Paragraph should read as follows: ‘The persons gathered in Dornach as the nucleaus of the Society recognize and endorse the view of the leadership at the Goetheanum:’ What now follows, right to the end of the Paragraph, should be within quotation marks. This is to do with my having said that here we ought to build on the purely human element. Consider the difference from what was said earlier. In the past it was said: The Anthroposophical Society is an association of people who recognize the brotherhood of man without regard to nationality—and so on, all the various points. This is an acceptance of principles and smacks strongly of a dogmatic confession. But a dogmatic confession such as this must be banned from a society of the most modern kind; and the Anthroposophical Society we are founding here is to be a society of the most modern kind. The passage shown here within quotation marks expresses the view of the leadership at the Goetheanum, and in Paragraph 3 one is reminded of one's attitude of agreement with the view of the leadership at the Goetheanum. We are not dealing with a principle. Instead we have before us human beings who hold this conviction and this view. And we wish to join with these people to form the Anthroposophical Society. The most important sentence is the one which states that the results, and that means all the results, of spiritual science can be equally understood by every human being and human soul but that, in contrast, for an evaluation of the research results a training is needed which is to be cultivated in the School of Spiritual Science within its three Classes. It is, then, not stated that people must accept brotherhood without regard to nation or race and so on, but it is stated that it is the conviction of those who up till now have been entrusted with the leadership at the Goetheanum that what is cultivated there leads to this; it leads to brotherhood and whatever else is mentioned here. So by agreeing to this Paragraph one is agreeing with this conviction. This is what I wanted to say by way of further interpretation. DR TRIMLER: For the purpose of openness would it not be necessary here to state who constitutes the leadership at the Goetheanum? Otherwise ‘the leadership at the Goetheanum’ remains an abstract term. DR STEINER: In a following Paragraph of the Statutes the leadership of the School of Spiritual Science is mentioned, and at another point in the Statutes the Vorstand will be mentioned; the names of the members of the Vorstand will be stated. Presumably this will be sufficient for what you mean? However, the naming of the Vorstand will probably be in the final point of the Statutes, where it will be stated that the Vorstand and the leadership at the Goetheanum are one and the same. So if you thought it would be more fitting, we could say: ‘The persons gathered in Dornach as the nucleus of the Society recognize and endorse the view of the leadership at the Goetheanum which is represented by the Vorstand nominated by this foundation gathering.’ This could of course be added. So it would read: ‘recognize and endorse the view of the leadership at the Goetheanum which is represented by the Vorstand nominated by this foundation gathering’. This will do. Who else would like to speak? HERR LEINHAS: Does this constitute a contradiction with point 7 where it says that Rudolf Steiner organizes the School of Spiritual Science and appoints his collaborators and his possible successor? Supposing you were not to choose as your collaborators those who are in the Vorstand as it stands at the moment? DR STEINER: Why should there be a contradiction? You see, it is like this, as I have already said: Here, as the leadership at the Goetheanum, we shall have the Vorstand. And the Vorstand as it now stands will be joined, in the capacity of advisers, by the leaders of the different Sections of the School of Spiritual Science. In future, this will be the leadership of the Goetheanum. Do you still find this contradictory? HERR LEINHAS: No. HERR SCHMIDT: I have one worry: Someone reading the sentence ‘Research into these results, however, as well as competent evaluation of them, depends upon spiritual-scientific training ... ’ might gain the impression that something is being drummed into people. DR STEINER: What is being drummed in? HERR SCHMIDT: It is possible for people to gain this impression. Personally I would prefer it if we could say: ‘depends upon spiritual-scientific training, which is to be acquired step by step, and which is suggested in the published works of Dr Steiner’, so that the impression is not aroused of something that is not quite above-board or not quite comprehensible for outsiders. DR STEINER: But this would eliminate the essential point which must be included because of the very manner in which the lecture cycles must be treated. What we have to achieve, as I have already said, is the following: We must bring it about that judgments can be justified, not in the sense of a logical justification but in the sense that they must be based on a solid foundation, so that a situation can arise—not as regards a recognition of the results but as regards an assessment of the research—in which there are people who are experts in the subject matter and others who are not. In the subsequent Paragraph we dissociate ourselves from those who are not experts in the sense that we refuse to enter into any discussion with them. As I said, we simply want to bring about this difference in the same way that it exists in the field of the integration of partial differential equations. In this way we can work at a moral level against the possibility of someone saying: I have read Dr Steiner's book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and therefore I am fully competent to assess everything else that has been published. This is what must be avoided. Therefore the very point to be made is that on the basis of my published books it is not possible to form a judgment on all the other things that are discussed above and beyond these. It would be wrong if we were not to refuse such judgments. Herr Schmidt feels that he has been misunderstood. DR STEINER: It says here: ‘Research into these results, however, as well as competent evaluation of them, depends upon spiritual-scientific training, which is to be acquired step by step.’ Why is this not clear? It does not mean that anything is drummed into anybody but rather that as with everything in the world you have to learn something before you can allow yourself to form a judgment. What we are rejecting is the assumption that anthroposophical matters can be judged from other points of view. There is a history behind this too. Let me tell you about it, for all these formulations are based on the experience of decades, as I have already said. I once gave a cycle of lectures in Bremens50 to a certain group of people who were permitted to attend not so much on the basis of their intellectual capacity as on that of their moral maturity. Now there was a very well-known philosopher, a Platonist, who reckoned that anyone who had read the whole of Plato ought to be able to form a judgment about Anthroposophy. On this basis he sent people to me about whom he said: These are good philosophers so they ought to be allowed to attend, since they are capable of forming judgments. Of course they were less capable of forming judgments than were some quite simple, humble people whose very mood of soul made them capable of forming judgments. I had to exclude them. So it is important that particularly in the case of this Paragraph we are extremely accurate. And it would not be accurate if we were to say that the necessary schooling can be attained on the basis of my published books. The interpretation of what constitutes the necessary schooling is stated in Paragraph 8: ‘All publications of the Society shall be public, in the same sense as are those of other public societies. The publications of the School of Spiritual Science’—let us say in future the cycles—‘will form no exception as regards this public character; however, the leadership of the School reserves the right to deny in advance the validity of any judgment of these publications which is not based on the same training from which they have been derived. Consequently they will regard as justified no judgment which is not based on an appropriate preliminary training, as is also the common practice in the recognized scientific world. Thus’ and so on. So you see, the requirement in Paragraph 3 must accord with that in Paragraph 8. If you have another suggestion, please go ahead. But the one you suggested just now is quite impossible. HERR SCHMIDT: Perhaps there could be a reference to Paragraph 8 at this point, for instance in the form of a note which says that the published books reveal the principles of the schooling. DR STEINER: This could certainly be pointed out in a note. But this note belongs at the point where it is stated that all publications shall be public, including the books about the conditions of the schooling. That is where such a note should be put. But I thought that saying that all books shall be public, all publications shall be public, would include the fact that all books about the schooling would be public. FRÄULEIN X: Ought it not to say: anthroposophical spiritual science; ‘as well as competent evaluation of them, depends upon anthroposophical spiritual-scientific training?’ DR STEINER: What you want to bring out here is made quite clear in Paragraph 8 by the reference to Dornach. If we say ‘anthroposophical’ we have once again an abstract word. I especially want to express here that everything is concrete. Thus the spiritual-scientific training meant—it is shown in this Statute—is that represented in Dornach. If we say anthroposophical spiritual science we are unprotected, for of course anyone can give the name of Anthroposophy to whatever he regards as spiritual science. HERR VAN LEER: I would like the final sentence to be changed from ‘not only in the spiritual but also in the practical realm’ to: ‘in the spiritual as well as in the practical realm.’ DR STEINER: I formulated this sentence like this because I thought of it as being based on life. This is what I thought: It is easy for people to admit in what is said here that it can constitute the foundation for progress in the spiritual realm. This will meet with less contradiction—there will be some, but less—than that Anthroposophy can also lead to something in the practical realm. This is more likely to be contradicted. That is why I formulated this sentence in this way. Otherwise the two realms are placed side by side as being of equal value in such an abstract manner: ‘in the spiritual as well as in the practical realm’. My formulation is based on life. Amongst anthroposophists there are very many who will easily admit that a very great deal can be achieved in the spiritual realm. But many people, also anthroposophists, do not agree that things can also be achieved in the practical realm. That is why I formulated the sentence in this way. MR KAUFMANN: Please forgive me, but it seems to me that the contradiction between Paragraph 3 and Paragraph 7 pointed out by Herr Leinhas is still there. Paragraph 7 says: ‘The organizing of the School of Spiritual Science is, to begin with, the responsibility of Rudolf Steiner, who will appoint his collaborators and his possible successor.’ I was under the impression that the Vorstand suggested by Dr Steiner has been elected en bloc by the present gathering. But now if Paragraph 3 calls the Vorstand, elected at the foundation meeting, the leadership at the Goetheanum, this seems to contradict Paragraph 7. I had understood Paragraph 3 to mean the leadership at the Goetheanum to be Dr Steiner and such persons as he has already nominated or will nominate who, in their confidence in him as the leadership at the Goetheanum, in accordance with Paragraph 7, hold the views stated within quotation marks in Paragraph 3 which are recognized positively by those present at the meeting. But if this is carried out by the Vorstand of the Anthroposophical Society elected here, then this seems to me to be an apparent contradiction, at least in the way it is put. DR STEINER: I should like to ask when was the Vorstand elected? When was the Vorstand elected? MR KAUFMANN: I was under the impression that it was accepted when you proposed it; and the agreement of the meeting was expressed very clearly. DR STEINER: You must understand that I do not regard this as an election, and that is why just now I did not suggest: ‘the leadership at the Goetheanum which is represented by the Vorstand elected by this foundation gathering’ but ‘formed’. MR KAUFMANN: Is this Vorstand identical with that mentioned in Paragraph 7? DR STEINER: Surely the Vorstand cannot be identical with my single person if it consists of five different members! Mr Kaufmann asks once again. DR STEINER: No, it is not identical. Paragraph 7 refers to the establishment of the School of Spiritual Science which I sketched earlier on. We shall name the Vorstand in a final Paragraph. But I regard this Vorstand as being absolutely bound up with the whole constitution of the Statutes. I have not suggested this Vorstand as a group of people who will merely do my bidding but, as I have said, as people of whom each one will bear the full responsibility for what he or she does. The significance for me of this particular formation of this Vorstand is that in future it will consist of the very people of whom I myself believe that work can be done with them in the right way. So the Vorstand is in the first place the Vorstand of the Society. What is mentioned in Paragraph 7 is the leadership of the School of Spiritual Science. These are two things. The School of Spiritual Science will function in the future with myself as its leader. And the leaders of the different Sections will be what might be called the Collegium of the School. And then there will be the Vorstand of the Anthroposophical Society which you now know and which will be complemented by those leaders of the different Sections of the School of Spiritual Science who are not anyway members of the Vorstand. Is this not comprehensible? MR KAUFMANN: Yes, but in the way it is put it seems to me that the contradiction is still there. DR STEINER: What is contradictory? MR KAUFMANN: Reading the words, you gain the impression that the Vorstand has been nominated by you personally. This would contradict Paragraph 7. DR STEINER: Yes, but why is this not sufficient? It has nothing to do with Paragraph 7. Paragraph 7 refers only to the preceding Paragraph 5, the School of Spiritual Science. What we are now settling has nothing to do with Paragraph 7. We are only concerned here with the fact that the Vorstand has been formed. It has been formed in the most free manner imaginable. I said that I would take on the leadership of the Society. But I shall only do so if the Society grants me this Vorstand. The Society has granted me this Vorstand, so it is now formed. The matter seems to me to be as accurate as it possibly can be. Of course the worst thing that could possibly happen would be for the Statutes to express that the Vorstand had been ‘nominated’ by me. And this is indeed not the case in view of the manner in which the whole Society expressed its agreement, as occurred here. HERR KAISER: Please excuse me for being so immodest as to speak once again. As regards Paragraph 1,51 the only thing I would suggest is that you simply say ‘life’ and nothing else; not ‘intellectual life’ and not ‘life of the soul’, but simply ‘life’. With regard to point 3, I would not want to alter a single word in the version which Dr Steiner has given with almost mathematical precision. But in order to meet the concern of our respected friend I would merely suggest the omission of the words ‘which is to be acquired step by step’. DR STEINER: Yes, but then we do not express what ought to be expressed, namely that the schooling is indeed to be acquired step by step. We shall print on the cycles: First Class, Second Class, Third Class. And apart from this it is necessary to express in some way that there are stages within the schooling. These stages are quite simply a fact of spiritual science. Otherwise, you will agree, we have no way of distinguishing between schooling and dilettantism. Someone who has only just achieved the first stage of the schooling is a dilettante for the second and third stage. So I am afraid we cannot avoid wording it in this way. DR UNGER: I should like to suggest that we conclude the debate about this third point. A SPEAKER: I believe we should agree to recognize the formulation of Paragraph 1 as it has emerged from the discussion. ANOTHER: I should only like to make a small suggestion. A word that could be improved: the word ‘the same’A in ‘the same progress’ in the last sentence of Paragraph 3. I would like to see it deleted and replaced by ‘also progress’. DR STEINER: We could do this, of course. But we would not be—what shall I say?—using language in as meaningful a way. ‘Gleich’ is such a beautiful word, and one which in the German language, just in this kind of context, has gradually come to be used increasingly sloppily. It would be better to express ourselves in a way which still gives a certain fragrance to what we want to say. Wherever we can it is better to use concrete expressions rather than abstract ones. You see, I do actually mean ‘the same progress as in the other realms’. So that it reads: ‘These results are in their own way as exact as the results of genuine natural science. When they attain general recognition in the same way as these, they will bring about the same progress in all spheres ...’ Of course I do not want to insist on this. But I do think it is not at all a bad thing to retain, or bring back to recognition, a word in the German language which was originally so resonant, instead of replacing it by an abstract expression. We are anyway, unfortunately, even in language on the way to abstraction. Now we are in the following situation: Since an application to close the debate has been made, I ought to adjourn any further debate, if people still want to speak about Paragraph 3, till tomorrow. We should then not be able to vote on this Paragraph today. Please understand that I am obliged to ask you to vote on the application to close the debate. In the interests of proper procedure, please would those friends who wish the conclusion of the debate indicate their agreement. DR UNGER: I only meant the discussion on point 3. We are in the middle of the detailed debate. DR STEINER: Will those who are opposed to closing the debate please raise their hands. I am sorry, that is not possible! We shall now vote on the acceptance or rejection of Paragraph 3. Will those respected friends who are in favour of adopting point 3 please raise their hands. (They do.) Will those respected friends who are against it please raise their hands. (Nobody does.) Point 3 has thus been adopted at the second reading. Tomorrow we shall continue with the detailed debate, beginning with point 4. We shall gather, as we did today, after the lecture by Herr Jan Stuten on the subject of music and the spiritual world. So the continuation of the detailed debate will take place in tomorrow's meeting, which will begin at the same time as today. This afternoon at 4.30 there will be a performance of the Three Kings play.

|

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: What I Have To Say To The Older Members (Concerning the Youth Section of the School of Spiritual Science)

09 Mar 1924, Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The announcement of the “Section for the Spiritual Striving of Youth” at the Goetheanum has met with an encouraging response from young people. Representatives of the “Free Anthroposophical Society” and younger members living at the Goetheanum have expressed to the Executive Council of the Anthroposophical Society their wholehearted willingness to take part in the Council's intentions. |

| But the active members of the Anthroposophical Society will not leave the Executive Council in the lurch either. Because at the same time as I am receiving approval from one side, I am also receiving a letter from the other side that contains words to which anyone who belongs to the Anthroposophical Society with their heart must listen. “The day may come when we ‘young people’ will have to break away from the Anthroposophical Society, just as you once had to break away from the Theosophical Society.” This day would come if we in the Anthroposophical Society are unable to realize in the near future what is meant by the announcement of a “Youth Section”. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: What I Have To Say To The Older Members (Concerning the Youth Section of the School of Spiritual Science)

09 Mar 1924, Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

The announcement of the “Section for the Spiritual Striving of Youth” at the Goetheanum has met with an encouraging response from young people. Representatives of the “Free Anthroposophical Society” and younger members living at the Goetheanum have expressed to the Executive Council of the Anthroposophical Society their wholehearted willingness to take part in the Council's intentions. I see in both expressions valuable starting points for a good part of the work of our Society. If it can build a bridge between older and younger people of our age, then it will accomplish an important task. What can be read between the lines of the two letters can be put into words: our youth speaks in a tone whose timbre is new in the development of humanity. One feels that the soul's eye is not directed towards the continuation of what has been inherited from the past and can be increased in the present. It is turned towards the irruption of a new life from the regions where not time is developed but the eternal is revealed. If the older person wants to be understood by the youth today, he must let the eternal prevail as the driving force in his relationship to the temporal. And he must do this in a way that the youth understands. It is said that young people do not want to engage with old age, do not want to accept anything from the insight gained from it, from the experience matured by it. - The older person today expresses his displeasure at the behavior of young people. It is true: young people separate themselves from old age; they want to be among themselves. They do not want to listen to what comes from old age. One can become concerned about this fact. Because these young people will one day grow old. They will not be able to continue their behavior into old age. They want to be really young. They ask how you can be “really young”. They will no longer be able to do that when they themselves have entered old age. Therefore, the older person says, youth should abandon its arrogance and look up to old age again, to see the goal towards which its mind's eye must be directed. By saying this, one thinks that it is up to youth not to be attracted to the older person. But young people could do nothing other than look up to the older person and take them as a role model if they were really “old”. For the human soul, and especially the young soul, is such that it turns to what is foreign to it in order to unite it with itself. Now, however, young people today do not see something in the older person that seems both alien to them as a human being and worth appropriating. This is because the older person of today is not really “old”. He has absorbed the content of much, he can talk about much. But he has not brought this much to human maturity. He has grown older in years; but in his soul he has not grown with his years. He still speaks from the old brain as he spoke from the young. Youth senses this. It does not feel “maturity” when it is with older people, but rather its own young state of mind in the aged bodies. And so it turns away, because this does not appear to it to be truth. Through decades of knowledge in the field of knowledge, older people have developed the opinion that one cannot know anything about the spiritual in the things and processes of the world. When young people hear this, they must get the feeling that the older person has nothing to say to them, because they can get the “not knowing” themselves; they will only listen to the old person if the “knowledge” comes from him. Talking about “not knowing” is tolerable when it is done with freshness, with youthful freshness. But to hear about the “not knowing” when it comes to the brain that has grown old, that deserts the soul, especially the young soul. Today, young people turn away from older people not because they have grown old, but because they have remained young, because they have not understood how to grow old in the right way. Older people today need this self-knowledge. But one can only grow old in the right way if one allows the spirit in the soul to unfold. If this is the case, then one has in an aged body that which is in harmony with it. Then one will be able to offer young people not only what time has developed in the body, but what the eternal reveals out of the spirit. Wherever there is a sincere search for spiritual experience, there can be found the field in which young people can come together with older people. It is an empty phrase to say: you have to be young with young people. No, as an older person among young people, you have to understand the right way to be old. Young people like to criticize what comes from older people. That is their right. Because one day they will have to carry that to which the old have not yet brought in the progress of humanity. But one is not a real older person if one merely criticizes as well. Young people will put up with this for a while because they do not need to be annoyed by the contradiction; but in the end they will get tired of the “old young” because their voice is too rough and criticism has more life in youthful voices. In its search for the spirit, anthroposophy seeks to find a field in which young and old people can happily come together. The Executive Council of the Anthroposophical Society can be pleased that its announcement has been received by young people in the way that it has been. But the active members of the Anthroposophical Society will not leave the Executive Council in the lurch either. Because at the same time as I am receiving approval from one side, I am also receiving a letter from the other side that contains words to which anyone who belongs to the Anthroposophical Society with their heart must listen. “The day may come when we ‘young people’ will have to break away from the Anthroposophical Society, just as you once had to break away from the Theosophical Society.” This day would come if we in the Anthroposophical Society are unable to realize in the near future what is meant by the announcement of a “Youth Section”. Hopefully the active members of the Anthroposophical Society will go in the direction of the Executive Council at the Goetheanum, so that the day may come when it can be said of the “young”: We must unite more and more closely with Anthroposophy. This time I have spoken to the older members of the Anthroposophical Society about the “youth”; in the next issue I would like to tell the youth what is on my mind. |

| 240. Karmic Relationships VI: Lecture VII

18 Jul 1924, Arnheim Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond, E. H. Goddard, Mildred Kirkcaldy Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The Christmas Meeting was intended to be a fundamental renewal, a new foundation of the Anthroposophical Society. Up to the time of the Christmas Foundation Meeting I was always able to make a distinction between the Anthroposophical Movement and the Anthroposophical Society. |

| The Anthroposophical Society was then a kind of ‘administrative organ’ for the anthroposophical knowledge flowing through the Anthroposophical Movement. |

| When we think to-day of how the Anthroposophical Society exists in the world as the embodiment of the Anthroposophical Movement, we see a number of human beings coming together within the Anthroposophical Society. |

| 240. Karmic Relationships VI: Lecture VII

18 Jul 1924, Arnheim Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond, E. H. Goddard, Mildred Kirkcaldy Rudolf Steiner |

|---|