| 265a. Lessons for the Participants of Cognitive-Cultic Work 1906–1924: Celebration of Günther Wagner's 70th Birthday

06 Mar 1912, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Günther Wagner through Miss Mathilde Hoyer, who founded the first class of the Freie Waldorfschule Hannover (1926) at Easter 1926 (I have written a report about this in the newsletter of the General Anthroposophical Society “What is happening in the Anthroposophical Society”, No. 43 and 44 of October 21 and 28, 1928, following a suggestion by Mrs. |

| In a late lecture on karma, Rudolf Steiner called him the “doyen of the Anthroposophical Society” (literally: “... and perhaps the oldest member of the Anthroposophical Society, who is here today to our great joy – Mr. Günther Wagner, whom I would like to warmly welcome [like a kind of senior of the Anthroposophical Society here] – will remember how strong the resistance was at the time for much of what I incorporated into the Anthroposophical Society from the beginning. —- It was particularly about “practical karma exercises”. - See the karma lecture of September 5, 1924, beginning, volume IV, esoteric considerations, complete edition!). |

| 265a. Lessons for the Participants of Cognitive-Cultic Work 1906–1924: Celebration of Günther Wagner's 70th Birthday

06 Mar 1912, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Notes by Ida Knoch with additions by Lidia Gentilli-Arenson-Baratto and memories by Karl Rittersbacher Father on a chair wreathed with roses and greenery; Gretchen, Paula and I beside him. One to seven hammer blows at the beginning and end, otherwise always seven instead of the usual three. Prayer and so on as usual. I know that I speak from the heart and feelings of all when I first address these words to our dear brother Günther Wagner. (Reading of the mantric lines):

Many weeks ago I was already quite certain that such an intimate ceremony would take place today, but I did not know what I would say until this morning, when I opened my heart to the Masters of Wisdom and of the Harmony of Feelings to ask for their blessing for our dear brother Günther Wagner. Before what was seen there is related, I know that I am one with you, my dear sisters and brothers, in the expression of the love and loyalty we feel for our dear and loyal brother Günther Wagner. Dr. Steiner emphasizes how Father advised and helped everyone who approached him seeking comfort, strength and courage, how he worked everywhere in harmony, seeking harmony, with the same love and faithfulness as his soul, how he radiated all that he had gained through a long, hard, truth-seeking life as love; how he consecrated his strength to our Theosophical Society. Dr. Steiner fondly remembers many moments when he was able to be close to Father — and so on, and so on. It was not so much words that came to Dr. Steiner from the wise masters of the East when he opened his heart to them in meditation this morning, but more images, indirect images, so to speak. In a community like the one gathered here, he could tell something like what he would say now. First, images appeared, from which others emerged. There Dr. Steiner saw a member of the Order of St. Benedict, surrounded by other members of the same order; these were the abbot - Sinibald - and the elders of this monastic order. They were sitting together, as rarely happens, not absorbed in exercises or other prescriptions, but exchanging more personal thoughts. And the abbot, who became abbot of this order in 1227, told his elders about his father, how much he had clung to him, that this father had gone to Palestine with the leader of the Third Crusade, how the father had told of the many hardships, how he had gone through privations and suffering, how he had fought; but the father also told of life in the Orient, and for example how glass was made there, how the color purple was produced. And these stories of life in the Orient and its peculiarities made a great impression on the listening boy, even more than the stories of the battles. The father of the abbot also spoke of the fact that he and his fellow fighters had a strong feeling that what Frederick Barbarossa did in the crusade meant more than just the outward events would suggest. The father, who was a knight of St. John of Jerusalem, stood by as the body of the red-bearded emperor was pulled out of the Saleph River, and he knew that even though three distinct parts of the body were buried near Tyre, near Antioch, and near Tarsus, the birthplace of Paul, his soul had nevertheless flown back to Europe. The father had been a knight of St. John of Jerusalem, and the abbot always had a great affection for them, as well as for the Teutonic knights, although his uncle, his father's brother (?), was opposed to the order. During his theological studies, the abbot often wondered whether the idea was behind things, about this Aristotelian idea, or whether the idea existed before things, as Plato says. — He entered the Order of St. Benedict, prompted by long-standing family connections, and was also destined from the outset for a leading position in it. During the exercises, which lasted from four o'clock in the morning until sunset, it was very rare for the abbot and the elders of his order to come together for such a personal exchange of ideas, and everyone left, reflecting on what they had heard. The abbot sat alone for a long time, pondering what had been said. And when he then walked back along the path, the meditation path, with a look of kindness and love, he met an eight-year-old boy who also wore the robe of St. Benedict. Perhaps the boy was inspired by the mild gaze he saw in the abbot's eyes to ask a question that we can only describe as impertinent. — The image is strongly emotional at this point. — This eight-year-old boy in the robes of St. Benedict said to the abbot: “Reverend Father, I cannot form a mental image of God.” The abbot looked kindly at the boy after this bold speech; he did not answer, but walked away in silence. And only when he was so far away that the boy could no longer hear him did the abbot say, as if to himself: “It will take a long time before one can form a correct mental image of God.” My dear sisters and brothers, this is what occurred to me when I turned to the wise masters of the East, asking for blessings for our dear brother Günther Wagner. Everyone can now think of what they believe to be right according to their disposition. From the mildness of the look shown by the picture, there is no doubt in the mind of the one who told you this about the personality of the abbot. You should not accept such stories out of blind faith; everyone can form their own opinions. But the narrator of these pictures is, as I said, completely sure and certain about the person of the abbot.When the Rosicrucian conclusion was reached, Dr. Steiner placed three red roses next to the box with the blessed water and so on, and at the end he waved the censer over them several times extra. Then he said: “Now our dear Sister Helene Lehmann will take these three roses to our dear brother Günther Wagner as a token of our love and loyalty.” When Dr. Steiner had finally carried the box away and then passed by father again, he kissed him on each cheek. In a transcription of Ida Knoch's notes by Lidia Gentilli-Arenson-Baratto, the following additional personal comment can be found at the end: The red book from which Dr. Steiner read was a red book that Paula Hübbe-Schleiden had given him (said Gretchen Wagner). She then asked me who the boy would have become, which she never knew. I asked her in return whether she believed or had heard who the boy would be in this life. She replied very firmly that everyone knew at the time, and it was generally said that it was Dr. Steiner himself, only she would like to know who the boy had become, she didn't know, and no one told her at the time. That concluded our conversation, which took place today. - February 27, 1960. In addition, the following personal memories of Karl Rittersbacher of conversations with Günther Wagner are available, which he added to his typewritten transcription of Ida Knoch's notes of this hour by Nelly von Lichtenberg: I had several personal encounters with Mr. Günther Wagner through Miss Mathilde Hoyer, who founded the first class of the Freie Waldorfschule Hannover (1926) at Easter 1926 (I have written a report about this in the newsletter of the General Anthroposophical Society “What is happening in the Anthroposophical Society”, No. 43 and 44 of October 21 and 28, 1928, following a suggestion by Mrs. Marie Steiner). Mr. Wagner had founded a paint factory in Hannover. During a visit to his home in the fall of 1927, he told me that the colors were still rubbed by hand and that he had 20 employees. I also learned that at the age of 50, he handed over the factory, which had grown to around 200 workers, to his son-in-law, who had been his senior traveler: Fritz Beindorff, who later became a senator in Hannover. This grand master of a freemason association had no time for the newly founded Free Waldorf School. I learned this drastically during a personal visit to his office. Mr. Günther Wagner, as he told me, lived on a pension he received in Berlin and Lugano. In Berlin, he worked as a librarian for the Theosophical Society, translating literature from Indian into German. He and some friends became aware of Dr. Rudolf Steiner and reported how he was instrumental in helping the Theosophical Society in Germany come into being. To do so, seven branches had to exist, each with at least seven members. This was achieved by recruiting in Leipzig. Then Dr. Rudolf Steiner was appointed as Secretary General. When Günther Wagner and his nurse, Paula Hübbe-Schleiden, née Stryczek, separated in 1912/13, it was clear to them that they could only go with Rudolf Steiner (literally to me!). After the above conversation – as Günther Wagner said during a visit – Rudolf Steiner asked him into the next room and said: “You were the abbot and I was the boy, your student. And so we meet again. And I then went from Monte Cassino, where this happened, to Cologne later. Günther Wagner added: “I went to Monte Cassino, but I had no memories whatsoever. I told Emil Bock all this. He said to me: But Mr. Wagner, you should have put on a Benedictine robe and climbed up the old serpentine paths to remember something.” Mr. Wagner had a calm, bright look in his eyes that radiated kindness and bore witness to a deep inner peace. Even in old age, he still enjoyed playing the piano (Schubert, Impromptu by heart). He had a package of letters from Rudolf Steiner. In a late lecture on karma, Rudolf Steiner called him the “doyen of the Anthroposophical Society” (literally: “... and perhaps the oldest member of the Anthroposophical Society, who is here today to our great joy – Mr. Günther Wagner, whom I would like to warmly welcome [like a kind of senior of the Anthroposophical Society here] – will remember how strong the resistance was at the time for much of what I incorporated into the Anthroposophical Society from the beginning. —- It was particularly about “practical karma exercises”. - See the karma lecture of September 5, 1924, beginning, volume IV, esoteric considerations, complete edition!). Rudolf Steiner is said to have given several members karmic hints earlier on the 70th birthday. Günther Wagner regretted that he could not financially support the newly founded school, since he only had the pension granted to him by his son-in-law. He also lived in the Black Forest in Frauenalb, where Fräulein Hoyer and I also visited him. When Mrs. Marie Steiner visited the then small school (two classes) in September 1927, Günther Wagner and Paula Hübbe-Schleiden were present. (See report in the newsletter!) Marie Steiner invited the small college to lunch at the hotel. A personal word: the content shared here, especially regarding karmic facts, meant for us at the time a concretization of our thinking about destiny and the laws of destiny. It sounded simple and seemed unmythically realistic. |

| 220. Fall and Redemption

21 Jan 1923, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| You see, if one grasps in this way the ideal whose reality can become conscious to the Anthroposophical Society, and if what arises from this consciousness becomes a force in our Society, then, even in people who wish us the worst, the opinion that the Anthroposophical Society could be a sect will disappear. |

| Now, through its very nature, the Anthroposophical Society has thoroughly worked its way out of the sectarianism in which it certainly was caught up at first, especially while it was still connected to the Theosophical Society. |

| Therefore I had to speak these days precisely about the more intimate tasks of the Anthroposophical Society. |

| 220. Fall and Redemption

21 Jan 1923, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

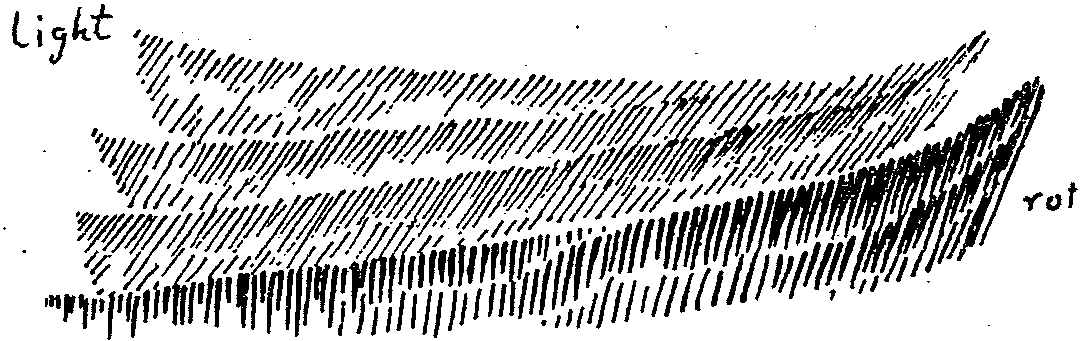

You have seen from these lectures that I feel duty bound to speak at this time about a consciousness that must be attained if we are to accomplish one of the tasks of the Anthroposophical Society. And to begin with today, let me point to the fact that this consciousness can only be acquired if the whole task of culture and civilization is really understood today from the spiritual-scientific point of view. I have taken the most varied opportunities to try, from this point of view, to characterize what is meant by the fall of man, to which all religions refer. The religions speak of this fall of man as lying at the starting point of the historical development of mankind; and in various ways through the years we have seen how this fall of man—which I do not need to characterize in more detail today—is an expression of something that once occurred in the course of human evolution: man's becoming independent of the divine spiritual powers that guided him. We know in fact that the consciousness of this independence first arose as the consciousness soul appeared in human evolution in the first half of the fifteenth century. We have spoken again and again in recent lectures about this point in time. But basically the whole human evolution depicted in myths and history is a kind of preparation for this significant moment of growing awareness of our freedom and independence. This moment is a preparation for the fact that earthly humanity is meant to acquire a decision-making ability that is independent of the divine spiritual powers. And so the religions point to a cosmic-earthly event that replaces the soul-spiritual instincts—which alone were determinative in what humanity did in very early times—with just this kind of human decision making. As I said, we do not want to speak in more detail about this now, but the religions did see the matter in this way: With respect to his moral impulses the human being has placed himself in a certain opposition to his guiding spiritual powers, to the Yahweh or Jehovah powers, let us say, speaking in Old Testament terms. If we look at this interpretation, therefore, we can present the matter as though, from a definite point in his evolution, man no longer felt that divine spiritual powers were active in him and that now he himself was active. Consequently, with respect to his overall moral view of himself, man felt that he was sinful and that he would have been incapable of falling into sin if he had remained in his old state, in a state of instinctive guidance by divine spiritual powers. Whereas he would then have remained sinless, incapable of sinning, like a mere creature of nature, he now became capable of sinning through this independence from the divine spiritual powers. And then there arose in humanity this consciousness of sin: As a human being I am sinless only when I find my way back again to the divine spiritual powers. What I myself decide for myself is sinful per se, and I can attain a sinless state only by finding my way back again: to the divine spiritual powers. This consciousness of sin then arose most strongly in the Middle Ages. And then human intellectuality, which previously had not yet been a separate faculty, began to develop. And so, in a certain way, what man developed as his intellect, as an intellectual content, also became infected—in a certain sense rightly—with this consciousness of sin. It is only that one did not say to oneself that the intellect, arising in human evolution since the third or fourth century A.D., was also now infected by the consciousness of sin. In the Scholastic wisdom of the Middle Ages, there evolved, to begin with, an ‘unobserved’ consciousness of sin in the intellect. This Scholastic wisdom of the Middle Ages said to itself: No matter how effectively one may develop the intellect as a human being, one can still only grasp outer physical nature with it. Through mere intellect one can at best prove that divine spiritual powers exist; but one can know nothing of these divine spiritual powers; one can only have faith in these divine spiritual powers. One can have faith in what they themselves have revealed either through the Old or the New Testament. So the human being, who earlier had felt himself to be sinful in his moral life—‘sinful’ meaning separated from the divine spiritual powers—this human being, who had always felt morally sinful, now in his Scholastic wisdom felt himself to be intellectually sinful, as it were. He attributed to himself an intellectual ability that was effective only in the physical, sense-perceptible world. He said to himself: As a human being I am too base to be able to ascent through my own power into those regions of knowledge where I can also grasp the spirit. We do not notice how connected this intellectual fall of man is to his general moral fall. But what plays into our view of human intellectuality is the direct continuation of his moral fall. When the Scholastic wisdom passes over then into the modern scientific view of the world, the connection with the old moral fall of man is completely forgotten. And, as I have often emphasized, the strong connection actually present between modern natural-scientific concepts and the old Scholasticism is in fact denied altogether. In modern natural science one states that man has limits to his knowledge, that he must be content to extend his view of things only out upon the sense-perceptible physical world. A Dubois-Reymond, for example, and others state that the human being has limits to what he can investigate, has limits to his whole thinking, in fact. But that is a direct continuation of Scholasticism. The only difference is that Scholasticism believed that because the human intellect is limited, one must raise oneself to something different from the intellect—to revelation, in fact—when one wants to know something about the spiritual world. The modern natural-scientific view takes half, not the whole; it lets revelation stay where it is, but then places itself completely upon a standpoint that is possible only if one presupposes revelation. This standpoint is that the human ability to know is too base to ascend into the divine spiritual worlds. But at the time of Scholasticism, especially at the high point of Scholasticism in the middle of the Middle Ages, the same attitude of soul was not present as that of today. One assumed then that when the human being used his intellect he could gain knowledge of the sense-perceptible world; and he sensed that he still experienced something of a flowing together of himself with the sense-perceptible world when he employed his intellect. And one believed then that if one wanted to know something about the spiritual one must ascend to revelation, which in fact could no longer be understood, i.e., could no longer be grasped intellectually. But the fact remained unnoticed—and this is where we must direct our attention!—that spirituality flowed into the concepts that the Schoolmen, set up about the sense world. The concepts of the Schoolmen were not as unspiritual as ours are today. The Schoolmen still approached the human being with the concepts that they formed for themselves about nature, so that the human being was not yet completely excluded from knowledge. For, at least in the Realist stream, the Schoolmen totally believed that thoughts are given us from outside, that they are not fabricated from within. Today we believe that thoughts are not given from outside but are fabricated from within. Through this fact we have gradually arrived at a point in our evolution where we have dropped everything that does not relate to the outer sense world. And, you see, the Darwinian theory of evolution is the final consequence of this dropping of everything unrelated to the outer sense world. Goethe made a beginning for a real evolutionary teaching that extended as far as man. When you take up his writing in this direction, you will see that he only stumbled when he tried to take up the human being. He wrote excellent botanical studies. He wrote many correct things about animals. But something always went wrong when he tried to take up the human being. The intellect that is trained only upon the sense world is not adequate to the study of man. Precisely Goethe shows this to a high degree. Even Goethe can say nothing about the human being. His teaching on metamorphosis does not extend as far as the human being. You know how, within the anthroposophical world view, we have had to broaden this teaching on metamorphosis, entirely in a Goethean sense, but going much further. What has modern intellectualism actually achieved in natural science? It has only come as far as grasping the evolution of animals up to the apes, and then added on the human being without being able inwardly to encompass him. The closer people came to the higher animals, so to speak, the less able their concepts became to grasp anything. And it is absolutely untrue to say, for example, that they even understand the higher animals. They only believe that they understand them. And so our understanding of the human being gradually dropped completely out of our understanding of the world, because understanding dropped out of our concepts. Our concepts became less and less spiritual, and the unspiritual concepts that regard the human being as the mere endpoint of the animal kingdom represent the content of all our thinking today. These concepts are already instilled into our children in the early grades, and our inability to look at the essential being of man thus becomes part of the general culture. Now you know that I once attempted to grasp the whole matter of knowledge at another point. This was when I wrote The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity and its prelude Truth and Science although the first references are present already in my The Science of Knowing: Outline of an Epistemology Implicit in the Goethean World View written in the 1880's. I tried to turn the matter in a completely different direction. I tried to show what the modern person can raise himself to, when—not in a traditional sense, but out of free inner activity—he attains pure thinking, when he, attains this pure, willed thinking which is something positive and real, when this thinking works in him. And in The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity I sought, in fact, to find our moral impulses in this purified thinking. So that our evolution proceeded formerly in such a way that we more and more viewed man as being too base to act morally, and we extended this baseness also into our intellectuality. Expressing this graphically, one could say: The human being developed in such a way that what he knew about himself became less and less substantial. It grew thinner and thinner (light color). But below the surface, something continued to develop (red) that lives, not in abstract thinking, but in real thinking.  Now, at the end of the 19th century, we had arrived at the point of no longer noticing at all what I have drawn here in red; and through what I have drawn here in a light color, we no longer believed ourselves connected with anything of a divine spiritual nature. Man's consciousness of sin had torn him out of the divine spiritual element; the historical forces that were emerging could not take him back. But with The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity I wanted to say: Just look for once into the depths of the human soul and you will find that something has remained with us: pure thinking, namely, the real, energetic thinking that originates from man himself, that is no longer mere thinking, that is filled with experience, filled with feeling, and that ultimately expresses itself in the will. I wanted to say that this thinking can become the impulse for moral action. And for this reason I spoke of the moral intuition which is the ultimate outcome of what otherwise is only moral imagination. But what is actually intended by The Philosophy of Spiritual Activity can become really alive only if we can reverse the path that we took as we split ourselves off more and more from the divine spiritual content of the world, split ourselves off all the way down to intellectuality. When we again find the spirituality in nature, then we will also find the human being again. I therefore once expressed in a lecture that I held many years ago in Mannheim that mankind, in fact, in its present development, is on the point of reversing the fall of man. What I said was hardly noticed, but consisted in the following: The fall of man was understood to be a moral fall, which ultimately influenced the intellect also. The intellect felt itself to be at the limits of its knowledge. And it is basically one and the same thing—only in a somewhat different form—if the old theology speaks of sin or if Dubois-Reymond speaks of the limits of our ability to know nature. I indicated how one must grasp the spiritual—which, to be sure, has been filtered down into pure thinking—and how, from there, one can reverse the fall of man. I showed how, through spiritualizing the intellect, one can work one's way back up to the divine spiritual. Whereas in earlier ages one pointed to the moral fall of man and thought about the development of mankind in terms of this moral fall of man, we today must think about an ideal of mankind: about the rectifying of the fall of man along a path of the spiritualization of our knowing activity, along a path of knowing the spiritual content of the world again. Through the moral fall of man, the human being distanced himself from the gods. Through the path of knowledge he must find again the pathway of the gods. Man must turn his descent into an ascent. Out of the purely grasped spirit of his own being, man must understand, with inner energy and power, the goal, the ideal, of again taking the fall of man seriously. For, the fall of man should be taken seriously. It extends right into what natural science says today. We must find the courage to add to the fall of man, through the power of our knowing activity, a raising of man out of sin. We must find the courage to work out a way to raise ourselves out of sin, using what can come to us through a real and genuine spiritual-scientific knowledge of modern times. One could say, therefore: If we look back into the development of mankind, we see that human consciousness posits a fall of man at the beginning of the historical development of mankind on earth. But the fall must be made right again at some point: It must be opposed by a raising of man. And this raising of man can only go forth out of the age of the consciousness soul. In our day, therefore, the historic moment has arrived when the highest ideal of mankind must be the spiritual raising of ourselves out of sin. Without this, the development of mankind can proceed no further. That is what I once discussed in that lecture in Mannheim. I said that, in modern times, especially in natural-scientific views, an intellectual fall of man has occurred, in addition to the moral fall of man. And this intellectual fall is the great historical sign that a spiritual raising of man must begin. But what does this spiritual raising of man mean? It means nothing other, in fact, than really understanding Christ. Those who still understood something about him, who had not—like modern theology—lost Christ completely, said of Christ that he came to earth, that he incarnated into an earthly body as a being of a higher kind. They took up what was proclaimed about Christ in written traditions. They spoke, in fact, about the mystery of Golgotha. Today the time has come when Christ must be understood. But we resist this understanding of Christ, and the form this resistance takes is extraordinarily characteristic. You see, if even a spark of what Christ really is still lived in those who say that they understand Christ, what would happen? They would have to be clear about the fact that Christ, as a heavenly being, descended to earth; he therefore did not speak to man in an earthly language, but in a heavenly one. We must therefore make an effort to understand him. We must make an effort to speak a cosmic, extraterrestrial language. That means that we must not limit our knowledge merely to the earth, for, the earth was in fact a new land for Christ. We must extend our knowledge out into the cosmos. We must learn to understand the elements. We must learn to understand the movements of the planets. We must learn to understand the star constellations, and their influence on what happens on earth. Then we draw near to the language that Christ spoke. That is something, however, that coincides with our spiritual raising of man. For why was man reduced to understanding only what lives on earth? Because he was conscious of sin, in fact, because he considered himself too base to be able to grasp the world in its extraterrestrial spirituality. And that is actually why people speak as though man can know nothing except the earthly. I characterized this yesterday by saying: We understand a fish only in a bowl, and a bird only in a cage. Certainly there is no consciousness present in our civilized natural science that the human being can raise himself above this purely earthly knowledge; for, this science mocks any effort to go beyond the earthly. If one even begins to speak about the stars, the terrible mockery sets in right away, as a matter of course, from the natural-scientific side. If we want to hear correct statements about the relation of man to the animals, we must already turn our eye to the extraterrestrial world, for only the plants are still explainable in earthly terms; the animals are not. Therefore I had to say earlier that we do not even understand the apes correctly, that we can no longer explain the animals. If one wants to understand the animals, one must take recourse to the extraterrestrial, for the animals are ruled by forces that are extraterrestrial. I showed you this yesterday with respect to the fish. I told you how moon and sun forces work into the water and shape him out of the water, if I may put it so. And in the same way, the bird out of the air. As soon as one turns to the elements, one also meets the extraterrestrial. The whole animal world is explainable in terms of the extraterrestrial. And even more so the human being. But when one begins to speak of the extraterrestrial, then the mockery sets in at once. The courage to speak again about the extraterrestrial must grow within a truly spiritual-scientific view; for, to be a spiritual scientist today is actually more a matter of courage than of intellectuality. Basically it is a moral issue, because what must be opposed is something moral: the moral fall of man, in fact. And so we must say that we must in fact first learn the language of Christ, the language ton ouranon, the language of the heavens, in Greek terms. We must relearn this language in order to make sense out of what Christ wanted to do on earth. Whereas up till now one has spoken about Christianity and described the history of Christianity, the point now is to understand Christ, to understand him as an extraterrestrial being. And that is identical with what we can call the ideal of raising ourselves from sin. Now, to be sure, there is something very problematical about formulating this ideal, for you know in fact that the consciousness of sin once made people humble. But in modern times they are hardly ever humble. Often those who think themselves the most humble are the most proud of all. The greatest pride today is evident in those who strive for a so-called ‘simplicity’ in life. They set themselves above everything that is sought by the humble soul that lifts itself inwardly to real, spiritual truths, and they say: Everything must be sought in utter simplicity. Such naive natures—and they also regard themselves as naive natures—are often the most proud of all today. But nevertheless, during the time of real consciousness of sin there once were humble people; humility was still regarded as something that mattered in human affairs. And so, without justification, pride has arisen. Why? Yes, I can answer that in the same words I used here recently. Why has pride arisen? It has arisen because one has not heard the words “Huckle, get up!” [From the Oberufer Christmas plays.] One simply fell asleep. Whereas earlier one felt oneself, with full intensity and wakefulness, to be a sinner, one now fell into a gentle sleep and only dreamed still of a consciousness of sin. Formerly one was awake in one's consciousness of sin; one said to oneself: Man is sinful if he does not undertake actions that will again bring him onto the path to the divine spiritual powers. One was awake then. One may have different views about this today, but the fact is that one was awake in one's acknowledgment of sinfulness. But then one dozed off, and the dreams arrived, and. the dreams murmured: Causality rules in the world; one event always causes the following one. And so finally we pursue what we see in the starry heavens as attraction and repulsion of the heavenly bodies; we take this all the way down into the molecule; and then we imagine a kind of little cosmos of molecules and atoms. And the dreaming went further. And then the dream concluded by saying: We can know nothing except what outer sense experience gives us. And it was labeled ‘supernaturalism’ if anyone went beyond sense experiences. But where supernaturalism begins, science ends. And then, at gatherings of natural scientists, these dreams were delivered in croaking tirades like Dubois-Reymond's Limits of Knowledge. And then, when the dream's last notes were sounded—a dream does not always resound so agreeably; sometimes it is a real nightmare—when the dream concluded with “Where supernaturalism begins, science ends,” then not only the speaker but the whole natural-scientific public sank down from the dream into blessed sleep. One no longer needed any inner impulse for active inner knowledge. One could console oneself by accepting that there are limits, in fact, to what we can know about nature, and that we cannot transcend these limits. The time had arrived when one could now say: “Huckle, get up! The sky is cracking!” But our modern civilization replies: “Let it crack! It's old enough to have cracked before!” Yes, this is how things really are. We have arrived at a total sleepiness, in our knowing activity. But into this sleepiness there must sound what is now being declared by spiritual-scientific anthroposophical knowledge. To begin with, there must arise in knowledge the realization that man is in a position to set up the ideal within himself that we can raise ourselves from sin. And that in turn is connected with the fact that along with a possible waking up, pride—which up till now has only been present, to be sure, in a dreamlike way—will grow more than ever. And (I say this of course without making any insinuations) it has sometimes been the case that in anthroposophical circles the raising of man has not yet come to full fruition. Sometimes, in fact, this pride has reached—I will not say a respectable—a quite unrespectable size. For, it simply lies in human nature for pride to flourish rather than the positive side. And so, along with the recognition that the raising of man is a necessity, we must also see that we now need to take up into ourselves in full consciousness the training in humility which we once exercised. And we can do that. For, when pride arises out of knowledge, that is always a sign that something in one's knowledge is indeed terribly wrong. For when knowledge is truly present, it makes one humble in a completely natural way. It is out of pride that one sets up a program of reform today, when in some social movement, let's say, or in the woman's movement one knows ahead of time what is possible, right, necessary, and best, and then sets up a program, point by point. One knows everything about the matter. One does not think of oneself at all as proud when each person declares himself to know it all. But in true knowledge, one remains pretty humble, for one knows that true knowledge is acquired only in the course of time, to use a trivial expression. If one lives in knowledge, one knows, with what difficulty—sometimes over decades—one has attained the simplest truths. There, quite inwardly through the matter itself, one does not become proud. But nevertheless, because a full consciousness is being demanded precisely of the Anthroposophical Society for humanity's great ideal today of raising ourselves from sin, watchfulness—not Hucklism, but watchfulness—must also be awakened against any pride that might arise. We need today a strong inclination to truly grasp the essential being of knowledge so that, by virtue of a few anthroposophical catchwords like ‘physical body,’ ‘etheric body,’ ‘reincarnation,’ et cetera, we do not immediately become paragons of pride. This watchfulness with respect to ordinary pride must really be cultivated as a new moral content. This must be taken up into our meditation. For if the raising of man is actually to occur, then the experiences we have with the physical world must lead us over into the spiritual world. For, these experiences must lead us to offer ourselves devotedly, with the innermost powers of our soul. They must not lead us, however, to dictate program truths. Above all, they must penetrate into a feeling of responsibility for every single word that one utters about the spiritual world. Then the striving must reign to truly carry up into the realm of spiritual knowledge the truthfulness that, to begin with, one acquired for oneself in dealing with external, sense-perceptible facts. Whoever has not accustomed himself to remaining with the facts in the physical sense world and to basing himself upon them also does not accustom himself to truthfulness when speaking about the spirit. For in the spiritual world, one can no longer accustom oneself to truthfulness; one must bring it with one. But you see, on the one hand today, due to the state of consciousness in our civilization, facts are hardly taken into account, and, on the other hand, science simply suppresses those facts that lead onto the right path. Let us take just one out of many such facts: There are insects that are themselves vegetarian when fully grown. They eat no meat, not even other insects. When the mother insect is ready to lay her fertilized eggs, she lays them into the body of another insect, that is then filled with the eggs that the insect mother has inserted into it. The eggs are now in a separate insect. Now the eggs do not hatch out into mature adults, but as little worms. But at first they are in the other insect. These little worms, that will only later metamorphose into adult insects, are not vegetarian. They could not be vegetarian. They must devour the flesh of the other insect. Only when they emerge and transform themselves are they able to do without the flesh of other insects. Picture that: the insect mother is herself a vegetarian. She knows nothing in her consciousness about eating meat, but she lays her eggs for the next generation into another insect. And furthermore; if these insects were now, for example, to eat away the stomach of the host insect, they would soon have nothing more to eat, because the host insect would die. If they ate away any vital organ, the insect could not live. So what do these insects do when they hatch out? They avoid all the vital organs and eat only what the host insect can do without and still live. Then, when these little insects mature, they crawl out, become vegetarian, and proceed to do what their mother did. Yes, one must acknowledge that intelligence holds sway in nature. And if you really study nature, you can find this intelligence holding sway everywhere. And you will then think more humbly about your own intelligence, for first of all, it is not as great as the intelligence ruling in nature, and secondly, it is only like a little bit of water that one has drawn from a lake and put into a water jug. The human being, in fact, is just such a water jug, that has drawn intelligence from nature. Intelligence is everywhere in nature; everything, everywhere is wisdom. A person who ascribes intelligence exclusively to himself is about as clever as someone who declares: You're saying that there is water out there in the lake or in the brook? Nonsense! There is no water in them. Only in my jug is there any water. The jug created the water. So, the human being thinks that he creates intelligence, whereas he only draws intelligence from the universal sea of intelligence. It is necessary, therefore, to truly keep our eye on the facts of nature. But facts are left out when the Darwinian theory is promoted, when today's materialistic views are being formulated; for, the facts contradict the modern materialistic view at every point. Therefore one suppresses these facts. One recounts them, to be sure, but actually aside from science, anecdotally. Therefore they do not gain the validity in our general education that they must have. And so one not only does not truly present the facts that one has, but adds a further dishonesty by leaving out the decisive facts, i.e., by suppressing them. But if the raising of man is to be accomplished, then we must educate ourselves in truthfulness in the sense world first of all and then carry this education, this habitude, with us into the spiritual world. Then we will also be able to be truthful in the spiritual world. Otherwise we will tell people the most unbelievable stories about the spiritual world. If we are accustomed in the physical world to being imprecise, untrue, and inexact, then we will recount nothing but untruths about the spiritual world. . You see, if one grasps in this way the ideal whose reality can become conscious to the Anthroposophical Society, and if what arises from this consciousness becomes a force in our Society, then, even in people who wish us the worst, the opinion that the Anthroposophical Society could be a sect will disappear. Now of course our opponents will say all kinds of things that are untrue. But as long as we are giving cause for what they say, it cannot be a matter of indifference to us whether their statements are true or not. Now, through its very nature, the Anthroposophical Society has thoroughly worked its way out of the sectarianism in which it certainly was caught up at first, especially while it was still connected to the Theosophical Society. It is only that many members to this day have not noticed this fact and love sectarianism. And so it has come about that even older anthroposophical members who were beside themselves when the Anthroposophical Society was transformed from a sectarian one into one that was conscious of its world task, even those who were beside themselves have quite recently gone aside again. The Movement for Religious Renewal, when it follows its essential nature, may be ever so far removed from sectarianism. But this Movement for Religious Renewal has given even a number of older anthroposophists cause to say to themselves: Yes, the sectarian element is being eradicated more and more from the Anthroposophical Society. But we can cultivate it again here! And so precisely through anthroposophists, the Movement for Religious Renewal is being turned into the crassest sectarianism, which truly does not need to be the case. One can see how, therefore, if the Anthroposophical Society wants to become a reality, we must positively develop the courage to raise ourselves again into the spiritual world. Then art and religion will flourish in the Anthroposophical Society. Although for now even our artistic forms have been taken from us [through the burning of the Goetheanum building on the night of December 31, 1922], these forms live on, in fact, in the being of the anthroposophical movement itself and must continually be found again, and ever again. In the same way, a true religious deepening lives in those who find their way back into the spiritual world, who take seriously the raising of man. But what we must eradicate in ourselves is the inclination to sectarianism, for this inclination is always egotistical. It always wants to avoid the trouble of penetrating into the reality of the spirit and wants to settle for a mystical reveling that basically is an egotistical voluptuousness. And all the talk about the Anthroposophical Society becoming much too intellectual is actually based on the fact that those who say this want, indeed, to avoid the thoroughgoing experience of a spiritual content, and would much rather enjoy the egotistical voluptuousness of soulful reveling in a mystical, nebulous indefiniteness. Selflessness is necessary for true anthroposophy. It is mere egotism of soul when this true anthroposophy is opposed by anthroposophical members themselves who then all the more drive anthroposophy into something sectarian that is only meant, in fact, to satisfy a voluptuousness of soul that is egotistical through and through. You see those are the things, with respect to our tasks, to which we should turn our attention. By doing so, we lose nothing of the warmth, the artistic sense, or the religious inwardness of our anthroposophical striving. But that will be avoided which must be avoided: the inclination to sectarianism. And this inclination to sectarianism, even though it often arrived in a roundabout way through pure cliquishness, has brought so much into the Society that splits it apart. But cliquishness also arose in the anthroposophical movement only because of its kinship—a distant one to be sure—with the sectarian inclination. We must return to the cultivation of a certain world consciousness so that only our opponents, who mean to tell untruths, can still call the Anthroposophical Society a sect. We must arrive at the point of being able to strictly banish the sectarian character trait from the anthroposophical movement. But we should banish it in such a way that when something arises like the Movement for Religious Renewal, which is not meant to be sectarian, it is not gripped right away by sectarianism just because one can more easily give it a sectarian direction than one can the Anthroposophical Society itself. Those are the things that we must think about keenly today. From the innermost being of anthroposophy, we must understand the extent to which anthroposophy can give us, not a sectarian consciousness, but rather a world consciousness. Therefore I had to speak these days precisely about the more intimate tasks of the Anthroposophical Society. |

| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: The International Delegates' Assembly

20 Jul 1923, Dornach |

|---|

| The two general meetings with all the delegates and members of the Anthroposophical Society on July 21 and 22 were recorded in shorthand. However, the two stenographers, Helene Finckh and Walter Vegelahn, only transcribed Rudolf Steiner's comments from their shorthand into longhand. |

| Abbreviated report of the International Assembly of Delegates of the Anthroposophical Society in Dornach from July 20-23, 1923, as well as some preliminary remarks for the founding of the International Anthroposophical Society at Christmas 1923 in Dornach. The loss of the Goetheanum through the fire on New Year's Eve 1923 was the most devastating event in the history of the anthroposophical movement and had to awaken the activity of the members more than ever. The year 1923 should show to what extent a new building can become reality from the united will of the society. |

| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: The International Delegates' Assembly

20 Jul 1923, Dornach |

|---|

[Except for the abbreviated general report by Albert Steffen and Guenther Wachsmuth, there are no complete minutes of all the discussions that took place. The two general meetings with all the delegates and members of the Anthroposophical Society on July 21 and 22 were recorded in shorthand. However, the two stenographers, Helene Finckh and Walter Vegelahn, only transcribed Rudolf Steiner's comments from their shorthand into longhand. The special discussions that took place alongside these two general meetings were not recorded, or only partially in note form, again with the exception of Rudolf Steiner's comments during the discussion with the German friends in the early morning of July 22. Otherwise, there are a few private reports. The complete report by Steffen and Wachsmuth is followed by a chronological overview of the days of the meeting with the verbatim reproduction of Rudolf Steiner's votes as recorded by the stenographers. Abbreviated report of the International Assembly of Delegates of the Anthroposophical Society in Dornach from July 20-23, 1923, as well as some preliminary remarks for the founding of the International Anthroposophical Society at Christmas 1923 in Dornach. The loss of the Goetheanum through the fire on New Year's Eve 1923 was the most devastating event in the history of the anthroposophical movement and had to awaken the activity of the members more than ever. The year 1923 should show to what extent a new building can become reality from the united will of the society. During the months since the fire at the Goetheanum, the firm wish of so many people in all countries of the world to rebuild the Goetheanum had been conveyed in telegrams, letters and other messages. An international committee had therefore convened the present assembly of delegates in the shortest possible time in order to give representatives from the various countries the opportunity to consult with each other regarding the action needed to realize the construction. At the preliminary meeting of the national delegates on Friday, July 20, the Congress Committee was elected: Mr. Albert Steffen as Chairman, Mr. George Kaufmann as Vice-Chairman, Dr. Guenther Wachsmuth and Mr. Heywood-Smith as Secretaries. This working committee was complemented by Dr. Ita Wegman, Mr. Scott Pyle, Mr. Leinhas, Mr. van Leer, Mr. de Haan. |

| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: The International Delegates' Assembly

23 Jul 1923, Dornach |

|---|

| I would like to say the following, but I expressly note that, of course, there is not the slightest bit of national or similar opinion behind it, but only facts. The Anthroposophical Society is only justified if it takes into account what can arise from anthroposophical knowledge from time to time, and, I would say, in relation to direct life. |

| Steffen has given the Anthroposophical Society the gift of being editor, to would be received in a completely different way than it actually is. |

| But to this day I have [doubts] whether the journal “Das Goetheanum” means anything to the anthroposophical movement according to the Anthroposophical Society. For us here today, there is still the possibility that the magazine “Goetheanum” is seen as something highly unnecessary by the membership. |

| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: The International Delegates' Assembly

23 Jul 1923, Dornach |

|---|

8 o'clock, Glass House: Meeting of the German friends in the presence of Rudolf Steiner. At the end of yesterday's general meeting, a German member asked when the German friends would meet to discuss their particular tasks. Dr. Carl Unger replied that the next day, from 8 o'clock in the morning, there would be a report for all friends who had come over from Germany. This early Sunday morning meeting of the German friends was introduced by Dr. Carl Unger, who set out the three points to be discussed: 1. the appeal for funds, 2. the Swiss resolution, 3. the moral fund. Steiner then took the floor. (Stenographic notes by Hedda Hummel.) Dornach, July 22, 1923, 8 o'clock in the morning. I will not be speaking for too long, as I want to leave the details to you. I would just like to say a few words: I would like to take this opportunity, when only German representatives are here, as it seems to me, to say something that should perhaps be known, or known about, only among the German representatives. For of course, the times are such today that the things that should actually be known are misunderstood in the most diverse ways. I would like to say the following, but I expressly note that, of course, there is not the slightest bit of national or similar opinion behind it, but only facts. The Anthroposophical Society is only justified if it takes into account what can arise from anthroposophical knowledge from time to time, and, I would say, in relation to direct life. You will see what I mean from the following suggestions. You see, it was of course a kind of naivety to believe that the weak forces of Central Europe could physically hold out against the whole world. I look back on the past times. It was naive to believe that when the coalition of the whole world outside Central Europe came into being. And it was clear from the beginning, since 1914, that it would be naive to believe that there could be any talk of an external victory for Central Europe. Central Europe has not really abandoned this belief until now. It always falls back on certain areas and will not be deterred from extending this belief, at least in the economic sphere, as long as the same is not experienced in the economic sphere as in the political sphere. It is, therefore, naive to believe that somehow, let us say, within the realm of the physical plan of Central Europe, the means of power of the whole world will be opposed. On the other hand, it must be realized that what the Central European, especially the German spirit has to say to the world has not yet been said and done, that Central Europe still has an enormous amount to accomplish for the world in spiritual terms, and that Central Europe should finally acquire an eye for the fact that in the, if I may put it this way, in the Maja, things sometimes even appear contrary to reality. So that what is currently happening in the world, both in the political and state and in the economic sphere, is actually the opposite of what is happening in the spiritual sphere. It is the true opposite. Because in reality the victories that are being won – and the economic victories will be too – are actually defeats; defeats in the face of evolving humanity. And it will be experienced that in spite of all striving for political and economic preponderance, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of all this, in spite of The spiritual must be taken from Central Europe! And there will arise in the world a longing to take the spirit from the place where one is actually enslaved in an outward way. And this will be intimately connected with the future shaping of the world. But I do not want it to be forgotten that such things are in many ways connected with human freedom in our present cultural epoch; that it is therefore simply not possible to miss the right moment; that in view of this, vigilance is necessary. And the Anthroposophical Society, above all, would have the task of being alert to what is happening in the immediate present. It would be very easy to miss the moment, which, one might say, is predetermined in history, when the view emerges from numerous centers in the periphery surrounding Central Europe: Yes, we have indeed achieved tremendous external power over Central Europe; but if we do not want to perish spiritually on earth, we must regard Central Europe as the source of spiritual life. Just imagine the unimaginable possibility that these judgments, more or less emotional judgments, would flare up in the various centers of the world and in Germany all the people would stand around selling their mouths and would not understand what is happening and what actually needs to be done. These things are the real basis for the formation of thoughts that underlie what is called, so to speak, exoterically — if I may put it that way — “the moral demand”. In our Anthroposophical Society, things must not remain empty words — of course, every idealistic phrase-maker also speaks of moral demands — but for us they must be supported by spiritual reality. Therefore, to give direction and strength to the spiritual muscles, I wanted to preface these few words. [The following discussion was about the organization of work in German society, the possibilities of contributing to the financing of construction, and the question of opponents. The continuation was postponed until 3 p.m. It was about the Lempp case, see page 596 for more information.] 10 a.m., carpentry workshop: Second General Assembly of the delegates and members of the Anthroposophical Society. (See the abbreviated general report by Albert Steffen and Dr. Guenther Wachsmuth.) According to the shorthand notes, the speakers were Albert Steffen, Herbert]. Heywood-Smith, Emil Leinhas, Dr. Wachsmuth, William Scott Pyle, George Kaufmann, Lieutenant-Colonel Seebohm, Jan Stuten, Miss Henström from Stockholm, Miss Woolley from London, Baron Walleen from Denmark, Miss Henström, Lina Schwarz from Milan about a circular letter to the Italian members about the work in Dornach and asks Rudolf Steiner for a meditation to be done together. Dr. Steiner's reply: I can only discuss things of this kind in lectures, not in meetings that actually have a different character. Things of this kind belong in lectures. Then Margarita Woloschin speaks for the Russian friends, Ludwig Polzer-Hoditz, Albert Steffen, Dr. Blümel. George Kaufmann provides a summary in English. Rudolf Steiner: It seems to me as if we are now at the end of the conference and I would like to say what I still have to say at the end of the lecture (his evening lecture). Albert Steffen now closes the meeting, pointing out that there are still many unresolved questions in the air, “for example, the most important one, that of a journal that would have to be formed for the exchange between the periphery and the center. But we have already discussed this question, and there are really major difficulties here that I alone cannot possibly resolve here... And so, as far as I am concerned, I would like to close the meeting today if no one else speaks, Rudolf Steiner: Regarding the newsletter — I do not consider the conference to be closed, so I do not want to say any kind of closing words, so to speak — but regarding the newsletter, which is often discussed, I would like to make the following comment. It is one thing to do many things; but it is quite another to recognize the necessity for something in a certain abstractness or to really get things going. We had to start somewhere and we really started with good reasons to found the magazine 'Das Goetheanum' here. Yes, dear friends, but for such a thing one needs the interest of the membership first. The “Goetheanum” is still an “inactive” magazine, as they say, which means that it has to be paid for. And it can be said that this is certainly connected with the lack of interest that has already been discussed. We here are always faced with the question: we have to start somewhere, at the beginning. But often the demand is then made to start at the end. That just can't be done. We have tried to give a picture of the ruined Goetheanum in the Goetheanum itself. Yesterday, Mr. Leinhas rightly emphasized: nothing has been done — the essays were, I believe, also printed in Anthroposophie in Germany — nothing has been done to make these things known. Apart from everything else that has to be considered when publishing a brochure, where is the prospect of such a brochure being received with any great enthusiasm and being supported in any way, other than what we have just described as the beginning? I believe that just as the Goetheanum magazine has a difficult existence here, so too does anthroposophy have a difficult existence out there in Germany. And a brochure that would be written in such a way that it would emerge from the heart of the matter — because, of course, you can't just fabricate an advertising brochure for anthroposophy —, well, that which would arise from the heart of anthroposophy would today again weigh heavily without there being any interest in it. Now, a newsletter requires a tremendous amount. It is easy to say that such a newsletter should be made; the reasons are, of course, hundreds that can be put forward for it. But what is needed above all is a revival of interest in the things that are being done. And it is not responsible to continue doing things when the old things are always left lying around. True, a brochure has been produced in Italy, but it has remained, I would say, in a small group of people in the Anthroposophical Society. We really need more support from our members for these things, because it is truly not an encouraging business to always have to talk about this. But it is all too often made necessary by the fact that things are talked about that really cannot be carried out in the way one imagines them, before one sees how taking by the hand develops for the beginning. Of course, one could even greet it as a good fact if every lecture given here were to multiply itself and then be carried everywhere by pigeon post. Of course it would be a very good thing. But in thought things cannot be carried out in this way; what would be necessary first is to go into the way in which the attempt to spread the things is made out of the matter itself. Just think about it: Mr. Steffen actually undertook to report much of what is going on here to the outside world – you can't speak of an attempt in this case, because what is complete in itself can also be considered an independent literary achievement –. Yes, of course, an educational course has been printed. But there was no response to these things from the membership, as there should have been; and there is no possibility of moving on to something more esoteric if we do not start by stimulating more interest among the membership in what is actually being done. It is the lack of interest in things that ultimately underlies the fact that everyone feels more or less unsatisfied with what is being done. But actually, perhaps one could, from the fact, for example, that within society there is someone like Mr. Steffen, who was rightly said at the last Swiss meeting here to be roughly the person who writes the best German style today; it is something that should at least be included as a positive thing. But really, this fact, for example, which means a great deal for the whole anthroposophical movement, that the anthroposophical movement includes the best German stylist in Mr. Steffen, should be an occasion for the journal “Das Goetheanum”, of which Mr. Steffen has given the Anthroposophical Society the gift of being editor, to would be received in a completely different way than it actually is. I notice so little response from the Society to what is actually in the Goetheanum. I could, when, I think it was a fortnight ago, an attempt was made to see if an echo could be evoked by challenging people to solve the riddles; you could see that at least people wanted to find out what was meant by these riddles.1 But otherwise far too little of what is in this 'Goetheanum' lives in society. Far too little lives in it. And really, do you believe that it is really extraordinarily difficult for Mr. Steffen or possibly for myself to stand up and say what the 'Goetheanum' actually is for a magazine. You can already... [space in the shorthand]. But you see, I have often heard the judgment: Yes, the “Goetheanum” is just not enough for us. But to this day I have [doubts] whether the journal “Das Goetheanum” means anything to the anthroposophical movement according to the Anthroposophical Society. For us here today, there is still the possibility that the magazine “Goetheanum” is seen as something highly unnecessary by the membership. This possibility still exists, after all. There is no real participation in such a thing, in which something of the best forces is actually put in here every week. Yes, it is not an invective that I would like to deliver here; but it is something to which I would like to draw attention when it is said: We cannot have enough of the “Goetheanum”, that is exoteric, people in the outside world can read that too, we need something much more esoteric. — Yes, just wait and see what fruits come when you first tend to the roots. But the roots must first be cultivated. That is already the case. We still have the whole afternoon ahead of us, and I will say what I want to say in conclusion in my lecture at the end of the conference. Emil Leinhas returns to the question of how to distribute the transcripts of Rudolf Steiner's lectures and says that it should also be considered “that Dr. Steiner repeatedly expressed his displeasure at the transcripts and also at their indiscriminate distribution, that it is not at all to his taste. One can well understand the desire for the transcripts, but one should also take into account Dr. Steiner's wish that the transcripts not be distributed in this way. Albert Steffen: So before I adjourn the meeting until 3:00 this afternoon, Rudolf Steiner: It would be very difficult to meet here in this hall this afternoon. Albert Steffen: We can immediately feel the difficulties that exist as long as there is no Goetheanum. The Germans wanted to meet in the Glass House, as far as I know, at three o'clock. This hall can only be used until four o'clock at the latest, because there is to be eurythmy at five o'clock. Rudolf Steiner: I did not want to schedule anything earlier, but just wanted to say: According to the program, the events at five and eight o'clock are also still part of the conference. Therefore, I did not want to say any closing words before the conference ended. Albert Steffen: I just have to thank Dr. Steiner for what he said about me as a writer. I must say that I see myself as a complete beginner in this respect, so that if I practise with words, I may perhaps achieve something to some extent. In any case, I am only just beginning. And I would at least like to thank the person who addressed me for the remark, who has the best command of the word in the present and in the past, for that person's trust. 3 p.m., Glass House: Continuation of the morning assembly of the Germans (no minutes). One participant, Hans Büchenbacher, reported on this in “Mitteilungen, herausgegeben vom Vorstand der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft in Deutschland” No. 7, Stuttgart, September 1923, as follows: At the meetings of the approximately eighty Germans present in Dornach, the friends from the Rhineland were in the foreground. They were convinced that they had significant contributions to make to the Society and that something important for the course of the entire conference had to come from them. At the same time, however, they were in a certain combative mood and particularly in an oppositional attitude towards the leadership of the Anthroposophical Society in Germany. But the following arose from this. At the beginning of the plenary assembly of the Germans on Sunday morning in the glass house, Dr. Steiner spoke in a deeply moving way about the spiritual task of the German people in particular. [Page 585] The fact that Dr. Steiner's words could not be discussed in the following debate was not so much due to the chairmanship of the meeting as to the attitude of the Rhenish friends, as characterized above. The whole discussion took on a chaotic course as a result, and Dr. Büchenbacher was forced to compare the situation with that at the Stuttgart delegates' conference in February. They did not even want to discuss the draft of a statement for Dr. Steiner, which Dr. Unger presented on the occasion of the Lempp affair.2 It was decided to hold another meeting in the afternoon to hear only the Rhenish friends at length, as they requested. They demanded that a Rhinelander should also preside over the meeting. The executive committee did not agree to this, which was entirely justified, and Mr. Leinhas, as chairman of the afternoon meeting, gave the Rhinelanders ample opportunity to say everything they had to say. The fact that the result that emerged was very modest would not have been a problem in itself. But, one may ask, was it necessary to talk to and fro fruitlessly for hours, sometimes in a rather testy manner, so that no time was left for Dr. Steiner's words, for the manifestation for him? Would that the discussions in September, which are so important for the Society, might not be conducted with an attitude that, as the Stuttgart delegates' conference has already shown, seriously endangers the existence of the Society, despite all the emphasis on one's own point of view. So much of the time available for discussion had passed before Mr. Leinhas was able to give the German friends an account of the Lempp affair. Dr. Steiner intervened with great sharpness and certainty, for which we can only be grateful to him, and presented this matter in its fundamental significance. The result was an understandable agitation of the assembly. Now people were urging a show of support for Dr. Steiner. He had already left, as the eurythmy performance was about to begin. There was no longer time for an orderly discussion... 5 p.m., Carpentry Shop: Eurythmy performance with introductory address by Rudolf Steiner (in CW 277). 8 p.m., carpentry workshop: 3rd lecture by Rudolf Steiner on “Three Perspectives on Anthroposophy” (in CW 225) with the announced farewell words to the conference participants:

|

| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: Words Following the Evening Lecture

19 Jan 1923, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| But as much as I dislike doing so, I would like to take this opportunity to point out that membership of the Anthroposophical Society imposes certain obligations, above all the obligation not to provide a target by spreading such rumors. |

| Of course, these things are the most unjustified attacks imaginable; but on the other hand, may I ask that, little by little, each individual member of the Anthroposophical Society practice the seriousness that is required there, and not tell all sorts of anecdotes that are then exploited by opponents. |

| Leave that to other people! In a certain way, being a member of the Anthroposophical Society obliges. 1. Upon returning from the first negotiations in Stuttgart. |

| 259. The Fateful Year of 1923: Words Following the Evening Lecture

19 Jan 1923, Dornach Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Today I have heard 1 that anthroposophists are carrying around all kinds of superfluous anecdotes, which, I might say, are being stirred up perhaps by this or that feeling about our great misfortune, the catastrophe of the Goetheanum. But as much as I dislike doing so, I would like to take this opportunity to point out that membership of the Anthroposophical Society imposes certain obligations, above all the obligation not to provide a target by spreading such rumors. 2 I must emphasize, because it is for the sake of the matter, not for the sake of the personal, that all the things that are done in this way by the members fall back on me and thus on the matter of the anthroposophical movement. We must exercise the utmost restraint in making accusations and, as Anthroposophists, we should really be able to develop such seriousness that we do not even do so in anecdotal form. For you can see from what you can find in the “Basler Nachrichten” today what terrible things we are involved in and what attacks we are exposed to. Of course, these things are the most unjustified attacks imaginable; but on the other hand, may I ask that, little by little, each individual member of the Anthroposophical Society practice the seriousness that is required there, and not tell all sorts of anecdotes that are then exploited by opponents. And the blame is usually laid at my door. I am always reluctant to preach morals in this way, but it is necessary from time to time. As I said, I have heard again today that such anecdotes have been spoken by anthroposophists. I would ask you, for the sake of the matter, for the sake of the holy matter, not to apologize for this seriousness and to carry around all kinds of anecdotes. Leave that to other people! In a certain way, being a member of the Anthroposophical Society obliges.

|

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: The School of Spiritual Science IV

10 Feb 1924, Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Those who join this school as members are in a completely different position than those who join the Anthroposophical Society. You become a member of this school after being a member of the Society for a sufficiently long time. |

| However, this means that the intention to join the school can be associated with the assumption of a range of duties and the awareness that one wants to be a representative of anthroposophical work. In contrast to the way in which Anthroposophy is presented within the Anthroposophical Society, it is not only absurd, but also quite tasteless when the opposing side repeatedly makes the defamatory accusation that Anthroposophy wants to exert a suggestive influence on anyone. |

| Everyone should judge for themselves whether they want to become a member of the school based on what they have come to know as a member of the Anthroposophical Society. When the school's leadership speaks of the duties that its members take on, they can be completely clear about what is meant. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: The School of Spiritual Science IV

10 Feb 1924, Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Those who join this school as members are in a completely different position than those who join the Anthroposophical Society. You become a member of this school after being a member of the Society for a sufficiently long time. You have come to know what anthroposophy wants, what it truly is. You have been able to form an opinion about what it can be worth to you. However, this means that the intention to join the school can be associated with the assumption of a range of duties and the awareness that one wants to be a representative of anthroposophical work. In contrast to the way in which Anthroposophy is presented within the Anthroposophical Society, it is not only absurd, but also quite tasteless when the opposing side repeatedly makes the defamatory accusation that Anthroposophy wants to exert a suggestive influence on anyone. Anyone who is in Anthroposophy knows this very well, or at least can know it. When members who have left the Society claim this, they usually know themselves that what they claim is objectively untrue. In the Society, no one is led to anthroposophy with blinders on. Therefore, they cannot become a member of the School without fully understanding the context of what anthroposophy sees as its task. Everyone should judge for themselves whether they want to become a member of the school based on what they have come to know as a member of the Anthroposophical Society. When the school's leadership speaks of the duties that its members take on, they can be completely clear about what is meant. It is not intended to imply anything other than that the school's leadership cannot fulfill its tasks if such duties are not taken on. The relationship between each member of the school and the leadership remains completely free, even if such duties are taken on. This is because the school leadership must also enjoy the freedom to act in accordance with the natural conditions of their work. They would not have this freedom if they were not allowed to say to those who are free to join or not to join the school: If I am to work with you, then you must take on the obligation to fulfill this or that condition. This should actually be self-evident and need not be stated. But it must be said, because all too often we hear: Those who join the school must give up some of their “human freedoms”. When this is said by members of the society, it is not surprising when malicious opponents spread the slander that Anthroposophy is gradually turning its adherents into will-less tools of what some people with bad intentions want. Anyone who has taken an interest in the Society's work for a sufficiently long time knows that Anthroposophy would lose all meaning the moment it undertook anything that went against the independent, level-headed, insightful will of its members. Anthroposophy cannot truly achieve its goals with will-less tools. For, in order to truly come to it, it requires precisely the free will of those involved. (Continued in the next issue.) |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: About the Leadership of this Newsletter and the Members' Share in It

27 Jan 1924, Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| This newsletter is titled “What's Going On in the Anthroposophical Society”. This title was given to it to suggest that in the future individual members should take a lively spiritual interest in everything that happens in the Society. |

| In this way, “what is going on in the world” can become “what is going on in the Anthroposophical Society”. And we need a broad outlook. We need a keen interest in all the phenomena of life in the world. |

| If the members see the newsletter in this way, the executive council of the Anthroposophical Society can make it what it should be according to the intentions of the Christmas Conference. |

| 37. Writings on the History of the Anthroposophical Movement and Society 1902–1925: About the Leadership of this Newsletter and the Members' Share in It

27 Jan 1924, Rudolf Steiner |

|---|