| 251. The History of the Anthroposophical Society 1913–1922: The Maturing of Humanity's Will to Truth

03 Jun 1917, Hamburg Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Up to the ages of 7, 14, 21, from child to youth to maiden, the phenomena are parallel to the processes in the body and soul. The education of the soul must go hand in hand with the processes in the body. From a certain age onwards, the human being becomes independent of the body – when they feel like an adult. |

| The soul then becomes independent of the body. This was quite different in the ancient Indian cultural period. There, until the age of fifty, the human being remained dependent on the physical and felt physically as a developing being. |

| Then, after the middle of life, one became aware of the ossification, the sclerotization of the body. In the states of sleep, the human being perceived the spirit, that which later became the Holy Spirit. |

| 251. The History of the Anthroposophical Society 1913–1922: The Maturing of Humanity's Will to Truth

03 Jun 1917, Hamburg Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Today I would like to discuss certain research results that are suitable for understanding many a puzzling aspect of the time, because only by understanding it is it possible to act in such a way that our actions are integrated as part of all human activity in the evolution of the world. One must place human life in a period of time in a part of the great scope of life on earth. Therefore, today I would like to discuss a development in the post-Atlantean period from a particular point of view. This winter in particular, many things have become clear to me, enabling me to say something important and characteristic about the time. Yesterday it was shown how thinking has become unreal, no longer powerfully intervening in the present. Where does this come from? Because it is naturally necessary in the course of development. It is sometimes more important to do something right in a small circle than to give abstract thoughts and program points. Let us consider the first post-Atlantean cultural period. Not even in the Middle Ages did people feel, think and want things as they do today. The state and mood of the soul change much more than one might think. Let us now turn our spiritual gaze back to the primeval Indian period, which does not fall within the time when writing originated. Life was quite different then than it was later. From one point of view, you will already see how it was different from the other times. Today, a person grows old by turning 30, 40, 50, 60, 70 years old. In the case of a child in the first years of life, the expressions of the soul are still entirely physical. Up to the ages of 7, 14, 21, from child to youth to maiden, the phenomena are parallel to the processes in the body and soul. The education of the soul must go hand in hand with the processes in the body. From a certain age onwards, the human being becomes independent of the body – when they feel like an adult. Today, it would be considered an imposition to read Schiller's “Tell” and Goethe's “Iphigenia” at the age of 35; one would have read them as a young man. Learning more at a later age is an imposition. Today, writers start at the age of 20. The soul then becomes independent of the body. This was quite different in the ancient Indian cultural period. There, until the age of fifty, the human being remained dependent on the physical and felt physically as a developing being. The change of the body is therefore so important. In those days, for example, it was known that a fifty-year-old had gone through five to six decades of what the body itself could give - for example, growth. Up to the age of 35, forces are integrated, the physical body increases. The spiritual life is contained in this growth. And when these forces break away, then, in healthy physicality, one feels that all material creation is based on the Father-God. The paternal principle, which rules and surges in everything, is felt to arise from one's own nature, from one's own bodily nature. Then, at the age of 35, the descent begins again. Today, people do not experience this. In those days, however, people felt that their strength was no longer rising from the paternal. They became aware, now in a subdued consciousness, that their strength was reaching a standstill, but then people felt connected to the spiritual environment, right up to heaven. What later came down as Christ revealed himself as a cosmic principle. Then, after the middle of life, one became aware of the ossification, the sclerotization of the body. In the states of sleep, the human being perceived the spirit, that which later became the Holy Spirit. Through this, people were witnesses here in life to the Father, Son and Spirit principle. In the age of ancient Persia, this consciousness had already receded, and was only tangible until the 40s, from the 42nd to the 48th year. The experience of the spirit principle had already become weaker, and the independence of the spirit was already less emphasized. But the social life was quite different. Young people looked up to the old with reverence because they knew that they had experienced the Father, the Son and the Spirit within themselves. They also understood death earlier. In the Egyptian period, this experience only extended into the thirties, from the 35th to the 42nd year. After that, man no longer came to an inner experience of dependence on the spirit. Therefore, there is no longer any understanding of the spirit in the Chaldean-Egyptian period. But there was still a sense of what later became of the spirit of the surging, weaving, oscillating Christ-life. In the Greco-Latin cultural period, it lasted until the 28th to 35th year (747 BC-1413 AD). Then one could only speak of the spirit in the mysteries, because normally one no longer felt it; only the Christ principle was felt. But this cosmic Christ principle ceased, only the Father principle could be experienced. But the people of this epoch still experienced the soul-spiritual within themselves, only they no longer experienced the outer spiritual. Then it goes back to the 34th, then to the 33rd year. Then the possibility of knowing anything other than the physical was cut off. Then the great and powerful event occurred - in the fourth post-Atlantic period - that in the body of Jesus of Nazareth, the Christ, who had previously been swaying up and down in the vicinity, that the Christ developed in the body of Jesus of Nazareth from the age of 30 to 33. Through this, a principle was gained for humanity that would otherwise have been lost. Mankind became ever younger, the Christ overcame death and introduced the son principle on Earth. When one makes the discovery for the first time, how the year of the death of Christ coincides with the 33rd year of mankind, then one experiences a moment when one senses the very basis of the Mystery of Golgotha. That means an enormous amount. Christianity can only be deepened by deepening our understanding. We still know very little today, and it is becoming more and more important to know more and more about the mystery of Golgotha. All knowledge can only be a servant to help us grasp this mystery in the right way. Then came our time, when a person is only capable of development up to the age of 27. Humanity is, in its declining age, 27 years old today. That is why spiritual science must appear. If we do not give our soul momentum, we will not get older than 27. It took a great deal for me to bring this secret out of the underground. This immaturity - up to 27 - we therefore also find in older people - this immaturity continues to shine and have an effect. In Helsingfors, I have already described how the imperfect, the immature, manifests itself in abstract ideals, how youth speaks of this, which has all the characteristic features of immaturity. Woodrow Wilson's ideal of the freedom of nations is such an ideal. These are all beautiful ideas, but: Wilson writes a note that is intended to make peace, and leads his own country into war. You cannot rule the world with such ideals. People lick their fingers when they have really nice ideas. But what good are they if they are not immersed in reality? - “The most capable should be in the right place.” - Such ideas, however beautiful they may be, are worth nothing if they are not immersed in reality. Eucken's philosophy is beautiful, but nowhere immersed in reality. Today's man is only capable of development up to the age of 27. We must understand that in the future, the spiritual-seclely must be developed independently. In the sixth post-Atlantic period, man is only capable of development from the age of 14 to 21, then no longer. Then “dementia praecox” will occur, which is not pleasant. Only truth, which is immersed in reality, is suitable for life practice. How do people think today? They think in an almost unreal way. They fall in love with their concepts. Later they themselves will become rigid and will fight the spiritual terribly. In the past, there were councils as a spiritual remedy. Later, in the sixth post-Atlantic period, souls will also be cured by remedies. The “sound mind” that causes man to consist only of body will be instilled against the views of the spirit. Such a decline must come if today's humanity continues to sleep thoughtlessly. What this humanity needs are harsh truths; not just those in which one pleasantly indulges. Humanity needs to be helped. Humanity suffers from a fear of spiritual knowledge. Hence materialism, hence the helpless fear of spiritual science. For spiritual science leads you into responsibility for the spiritual development of humanity. Those who sleep through the times do not notice this. But this spiritual slumber weighs heavily on them. I will give you an example: an essay on the cultural-political movement in Austria in the 1890s – spirit in politics. The thoughts are clever, but not immersed in reality. Without understanding today, one cannot act. Second example: Russians are mystically inclined, they say today, and thus throw sand into their eyes out of inability. In truth, it is like this:

One would like to have something other than tongue and words to indicate what time has so severely Therefore, opposing forces are at work to extinguish the light of life in spiritual science. Contradictions such as the following are part of life today: mysticism is the highest knowledge – and: mysticism is foolish enthusiasm. Spiritual science must speak the language of life, which is as deeply serious as life itself. It cannot be measured with the ordinary philistine language. It is precisely because spiritual science is so intimately connected with the needs of the time, precisely for this reason, that now – when everything, I might say, is preparing itself for it, on the one hand, spiritual science is really beginning to be taken seriously here and there, where it can be taken seriously – that the opposing spiritual forces are setting about extinguishing the light of life of this spiritual science. Do you see that it is necessary to apply completely new concepts and standards to cognition when approaching spiritual science from the usual, conventional cognition of today? People do not want to see this. And so this lamentable, infinitely foolish talk can arise, with all kinds of contradictions, which of course comes from spite, but not only from that, but above all from lack of understanding and from the will to lack of understanding. How can contradictions be pointed out in that which has emerged within spiritual science and its philosophical basis? Of course, anyone who does not take the standpoint of spiritual science but judges in a materialistic way can find such contradictions. But anyone who knows that spiritual science must be immersed in life must consider this immersion in life. Take a specific case! Suppose someone says: Mysticism is the stream of knowledge through which a person attempts to unite his own inner being with the spiritual that permeates and interweaves the world. Now take my Philosophy of Freedom or the writing Truth and Science, where the proof is to be provided that through purified thinking man enters into connection with the web of the world; then I must say: these books in particular correspond completely to the definition of true mysticism. I must therefore say: I claim the expression “true mysticism” for my world view. Therefore, when I want to point out today's mysticism, am I not allowed to point out all the confused talk, [am I not allowed to] denounce this nonsense as mysticism? I must indeed denounce it, must reject it, must therefore have the pure concept of mysticism in mind on the one hand, on the other hand, because I have life in mind, I must have the nonsense in mind as well. If someone comes along who looks at one side and says: “There he says that mysticism is the ideal of knowledge”; and on the other side he says: “Mysticism is based on all kinds of ecstasy” – contradiction! Such contradictions are part of life, and anyone who walks with life can always find these contradictions. But one must first succumb to abstractions if one wants to present such contradictions at all. Or take another thing, my dear friends! Today, of course, it is easy to say: I have presented the significance of Haeckelism for the scientific knowledge of the world. Yes, my dear friends, just take the following. Suppose someone describes Goethe's activity as a theater director; he takes into account nothing but what Goethe did as a theater director; but he points out that he was not a theater director like a Mr. So-and-so so, but [that he] was Goethe; that as a theater director, he carried out his duties in such a way that, in the background, he was always completely Goethe as a theater director; then he can certainly describe Goethe's activity as a theater director. Let us assume that someone who has shown in “Philosophy of Freedom” and “Truth and Science” how scientific materialism is rejected, who has shown how in everything matter as such rests on the spirit, may afterwards also show how the spirit reveals itself to matter, reveals itself in the phenomena that Haeckel described. For the one who wrote about Haeckel in 1899 and presented the justified, /gap in the transcript] who in 1894 established the refutation of materialism, for whom the representation means something quite different than for the one who did not have “Truth and Science”, “Philosophy of Freedom” but rather took Haeckel's own point of view. Now, one can understand the matter and will say: Of course, anyone who can appreciate Goethe as a whole may also portray Goethe as a theater director. The one who is a Holzbock – a journalist is named just like that, excuse me! – can portray Goethe as a theater director as if he were portraying Mr. So-and-so, and he cannot have more spirit in the portrayal. But the one who, in the complete spirit of Goethe, portrays Goethe as a theater director, that means something completely different. And so my characterization of Haeckel is something completely different, after the two books mentioned above [gap in the transcript], and one could assume [that it is not a materialist who is describing, but someone who describes the spiritual reality everywhere. ]. Therefore, anyone who is malicious can depict the contradictions. Goethe as a playwright, Goethe as the author of Faust, Goethe as theater director! Someone may say: Now this person used to think that Goethe is the author of Faust, and now he has revealed himself: He believes that Goethe is just a theater director! — Brought to its logical effect, what the folly is about the representation of Haeckelism is no different than if someone speaks like this. But it is necessary, my dear friends, for the truth to come to light, [that] one approaches spiritual science with the assumption that this spiritual science must speak a different language than abstract, rational and therefore materialistic science, [even] if it sometimes behaves in a spiritual or spiritualistic way. Today, one can be a follower of spiritualism and, precisely for that reason, be a blatant materialist in one's concepts, because, as a spiritualist, one is trying to have the spirit in front of oneself in the material phenomenon. However, one does not arrive at the truth if one does not decide to recognize how spiritual science must speak the language of life and must therefore be as versatile as life, and must therefore speak a different language than the one that has been spoken so far. For it would not be true, my dear friends, if I were to tell you that spiritual science must intervene so deeply in the impulses of humanity; it would not be true if I did not have to emphasize to you at the same time: spiritual science must speak a language in such a way that it cannot be approached and criticized in the ordinary philistine language; it must be misunderstood. But one must have this prerequisite that one must misunderstand it as a result. Of course, in this respect, because all the floodgates have been opened to it, one can criticize spitefulness; because when someone speaks from life, they themselves open all the floodgates to allow criticism to approach. You can also do it like Goesch, who takes everything I have said against one or the other and leaves out what I have said for one or the other; then you can [gap in transcript]. What must develop within that school of thought through which anthroposophically oriented spiritual science flows is, above all, a real sense of truth. Above all, one must have a real sense of truth in relation to events; one must never allow it to be reduced to adjusting any event to one's subjective needs, but one must describe events according to their objectivity. If someone has as little sense of truth as the Imperial Court Councillor Professor Max Seiling, he can, for example, write the sentence that is true, like all the other sentences by Professor Max Seiling are true, namely just as philistine and untrue: Well, yes, Dr. Steiner joined the Theosophical Society in order to represent the truths or the insights or the assertions of the Theosophical Society. Of course, [Seiling] knows very well that this is an objective untruth. For what was the matter? I started giving lectures in Berlin in 1900, 1901, based on what had emerged from my own research; those lectures were then printed in excerpt in the book “Mysticism in the Dawn of Modern Spiritual Life”. At that time I had read nothing at all of the literature that the English Theosophical Society had produced, and I may confess to you that this literature was absolutely far too amateurish for me — if I am to express my personal opinion. The matter was presented from the direct progress of my research. I had read nothing. What happened? It happened that these lectures, as they were available in print at the time, were translated into the “Theosophical Review” without my involvement; some of them were translated. As a result, I was invited to join the Theosophical Society. I never deigned to say anything other than what came from my own research. I didn't go after Haeckel either. Why shouldn't I have written that, since I wasn't connected to the Theosophical Society [gap in the transcript]. If you want to cure your cabbage with something sensible, why shouldn't that be done! Why shouldn't those who believe in cabbage be brought to their senses? I was in London. Mead, who was still an acquaintance of Blavatsky's and who contributed a great deal to Theosophical literature in a scholarly way, told me at the time: “This book ‘Mysticism in the Dawn of Modern Spiritual Life’ contains everything that is justified in literature; the rest is nothing!” Why should I not have said to myself: Well then, so be it, let people accept it! — That they then became furious when they saw how things developed, and when they had taken the cabbage to that over-cabbage state with the Alcyones — that they then became furious and raving mad about the further assertion of where the gap in the transcript] and the theosophical worldview are established at the same time, you couldn't let that stand. But there was never any break in the continuous development of what I had presented in my lectures and books. Of course, I do not speak of the Hierarchies in Philosophy of Freedom and Truth and Science; that was not my task. Besides, from the very fact that I have presented the matter from the most diverse sides, I have the right to expect that the same terms will not be applied to me as to many others. I have written a “Theosophy”; but before that I wrote the “Philosophy of Freedom”, “Truth and Science”, “Goethe's World View”, and before that I had written the book, which was then called “World and Life Views in the 19th Century”, and in it I set down much of what you can still see today, which was later developed, which was only a germ at the time. I have written a “Theosophy”; now what is contained in my world view is clearly indicated: “He is a theosophist!” This is just as clear as if someone had written a “chemistry” and one demanded of him that he had a chemical world view. I have written a book called “Theosophy” in which what is written in it is written from the point of view of Theosophy, just as one describes a certain area of the world. But the fact that someone should only have chemical thoughts when he has written a “chemistry” /gap in the transcript] means not building a system out of concepts, but judging from life; not setting up some new system, not founding some kind of sectarian movement, but grasping the spirituality of life in its various aspects in order to bring it to the world's consciousness, that is what matters: the truly concrete spirituality. You see, therefore, that it is simply an objective untruth when Seiling claims today that I would somehow simply copy the things of the Theosophical Society after having copied Haeckelianism for a while. One must have the will to truth, and that can only come from the will to spirituality. You can see, therefore, the sources from which what is asserting itself so spitefully today comes — in the addiction to insane inventions —, namely, to eliminate spiritual science in the form in which it actually arises out of the needs and longings of the time, because it cannot be fought. Fighting it is considered too inconvenient, because this spiritual science will emerge victoriously from this fight. Therefore, what is necessary now, when one wants to get involved in such things, must not be taken lightly. But I know that those of our dear friends who have a heart and mind for the seriousness of what is at stake in anthroposophically oriented spiritual science will probably agree with the two measures I have mentioned to you. The first: In the future, these private gatherings, which initially arose from the center of society and led to the most incredible gossip, must be avoided. I am sorry that I have to mention this here in Hamburg as well, although Hamburg is one of the cities that are more or less far removed from what is now occurring in such an untruthful manner. But all members need to know. One must not come with the objection that has just been raised in Munich, for example: “Everyone has to suffer because of these rioters.” – These rioters have been talked about long enough, something must be done that will permanently point out the seriousness of the situation and the sacredness of spiritual science for a long time. And the other necessary measure is that I authorize everyone, insofar as they themselves want, to talk about what has ever occurred or been said in these gatherings. What spiritual science is does not need to shy away from the light of day. Spiritual science can be brought into the full light of day with all esotericism. It needs to shy away from nothing, absolutely nothing, in the full light of day. Please forgive me, my dear friends, for having to point this out in all seriousness here in the presence of this society; but I have tried to make it clear that it is connected with higher, more far-reaching points of view points of view, for the reason that what is intended in anthroposophically oriented spiritual science creates out of a reality, creates out of the full reality, out of the developing reality. And it is necessary that we finally grasp this, that if we immerse ourselves in that which is currently to be overcome, we cannot arrive at a critique of it that not only speaks of something else, but must also speak of this other in a different way, must speak a completely new language. It is certainly a witty truth, my dear friends, when someone hears a person, when an Italian hears someone speak and says: “That's a language? That's nonsense, it contradicts every word I think!” The other person is speaking German. - It is very witty to say: “Every word contradicts the Italian.” You just have to learn the language first if you want to understand German when you are Italian. If you do not want to learn the - I would like to say - novel language in which spiritual science has to appear, then it is impossible to come to an understanding of spiritual science. My dear friends, it is absolutely necessary to grasp this quite deeply. This is one of the things that must be asserted again and again. Becoming friends with life, penetrating life, becoming related to life - that is what is necessary. And in the face of the seriousness that today's seeker must have, one can still make very special discoveries about those people in the present who believe that they can criticize this seriousness today. I once had to say the following at a general assembly in Berlin: When I approached Nietzsche years ago, the truth as such came before my soul in Nietzsche. What does truth mean in life? That can become a mystery; the role of truth in life? And it becomes a bloody mystery; / gap in the transcript] one gives one's heart's blood to answer the question about the value of truth, the question that is posed in such a haunting way in Nietzsche's “Beyond Good and Evil”, even though Nietzsche, bleeding to death precisely because of this question, soon afterwards fell into madness. The question is posed in such a way that one must penetrate to the very depths of the sources of human knowledge. This is a question that one must solve with one's heart's blood. Max Seiling finds, because I said at the time: “How can the problem arise according to the value of truth? One must solve this question with one's heart's blood. Especially with Nietzsche one can see it arise. can see it happening.” Of course, one then comes to the important realization of our anthroposophically oriented dictum, ‘Wisdom lies only in truth,’ but that can initially be a problem to be solved with the heart's blood. Max Seiling, when people told him that I had the “tastelessness” to speak of the bleeding heart, he had to read it in the “Mitteilungen” to believe that I had the “tastelessness” to speak like that. Today, we have to learn this and at the same time be convinced that Max Seiling von den Widersprüchen against the dictum had not yet spoken before his brochure was rejected, and only then came to speak as he then spoke after it had been rejected. It is important to see what flows from mere spite, from mere unwillingness to face the truth, not only from a general, but also from a deeper point of view. Dear ones, when one insults the other, it is necessary that the one who insults be treated with the first principle of the Anthroposophical Society, namely lovingly and benevolently, and that the one who is attacked should ask for forgiveness. The attacker is a person one should feel sorry for, and the one who is attacked should think: 'How easy it is to go wrong!' Therefore, it is unconscionable of me – and there will be those who say so even now – that I point out Seiling's slanders and invective in this way and do not say: 'He rants in the most hateful way, but I find it appropriate that, above all, general philanthropy should prevail and say: Well, it is understandable that such fruits must also come into the world, one must be grateful that someone points out the contradictions, not merely needing to believe in authority. — Certainly, this judgment is also possible; but you will see how far we would get with it. |

| 191. Meditatively Acquired Knowledge of Man: Social Understanding Through Spiritual Scientific Knowledge

04 Oct 1919, Dornach Translated by T. Van Vliet, Pauline Wehrle, Karla Kiniger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| These are predominantly at work in everything developing in the human being between seven and fourteen. Then comes the most important stage of all, from fourteen to twenty-one. |

| We have to educate ourselves to do consciously what was simply done unconsciously by man's blood in the past. For the strength in our blood is in the process of fading away. What would happen if a time were to come when human beings completely lost hold of their youth, and were unable to draw on their youthful forces, if there were no means of resorting to doing consciously what was once done unconsciously by the blood? |

| But people cannot be social if they do not see the human quality in one another, but live entirely within themselves. Human beings can only become social if they really meet one another in life, and something passes between them. |

| 191. Meditatively Acquired Knowledge of Man: Social Understanding Through Spiritual Scientific Knowledge

04 Oct 1919, Dornach Translated by T. Van Vliet, Pauline Wehrle, Karla Kiniger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

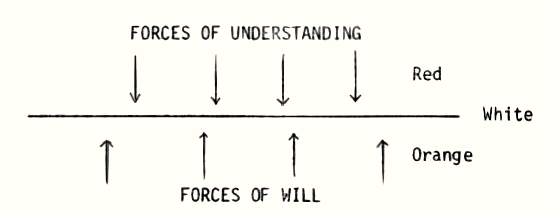

In the middle one of these three lectures there are a number of anthroposophical truths in particular that I would like to develop for you. We shall then see what a great impact on a person's everyday life these particular truths have, and that is what we will talk about tomorrow. Today I just want to draw you attention to some deeper aspects of the being of man. People very often do not ask the question as to which of man's forces are used to acquire knowledge of supersensible worlds. They try to answer this question merely by saying that there is a possibility of acquiring supersensible knowledge by means of certain forces in man. But what the actual connections are between these forces and man's being, they do not usually ask. That is why so little importance is attached to making knowledge of supersensible worlds really fruitful in ordinary life. It can be said that supersensible knowledge is becoming more and more essential to man, just in our time. In that case it is vital to understand what its connection is with ordinary everyday life. As you know, the first of the capacities that leads man into supersensible realms is the force of Imagination, the second capacity is the force of Inspiration and the third capacity the force of Intuition. The question now is whether these capacities need concern us at all except in their connection with knowledge of supersensible worlds or whether these capacities have any part to play in the rest of man's life?—You will see that the latter is the case. As my little book Education of the Child in the Light of Anthroposophy tells you, we can see human life running its course in three stages: from birth to the change of teeth, from the change of teeth to puberty, and from puberty till about the twenty-first year. If you do not regard man purely superficially you will be struck by the fact that the nature of man's development is entirely different in the three different seven-year stages. The pushing through of our permanent teeth, as I have often mentioned, is connected with the development of forces that are not merely confined, let us say, to our jaws or their neighbouring organs, but fill our whole physical body. There is work in progress within our physical body between birth and the seventh year, and this work comes to an end with the pushing through of our permanent teeth. It is obvious that the forces doing this work of developing the physical body are supersensible, isn't it? The perceptible body is only the material in which they work. These supersensible forces, active in the whole of man's organisation during the first seven years of his life, become, as it were, suspended when their purpose has been achieved and the permanent teeth have appeared. At the age of seven these forces go to sleep. They are hidden within the being of man; they go to sleep within him. And they can be drawn forth from your being when you do the sort of exercises I describe in Knowledge of the Higher Worlds as leading to Intuition. For the forces that are applied in the acquisition of intuitive knowledge are the same forces that you grow with at the time of life when this growth culminates in the change of teeth. These sleeping forces that are active within the human body until the seventh year are the forces you use in supersensible knowledge to reach Intuition. Now the forces that are active from the seventh year to the fourteenth year and go to sleep at puberty in the depths of the body, are drawn forth and form the power of Inspiration. And the forces that in bygone times used to be the source of youthful ideals between the fourteenth and the twenty-first year—it would be too much of an assertion to say that this still happens today—the forces that create organs in the physical body for these ideals of youth, are the same forces you can draw forth from their state of slumber and use for the acquisition of Imagination. From this you will see that the forces of Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition are not just any old forces got from we do not know where, but are the same forces as those we grow with from our birth to the age of twenty-one. So the forces that live in Imagination, Inspiration and Intuition are very healthy forces. They are the forces a human being uses for his healthy growth and that go to sleep within his body when the corresponding phases of growth are completed. I have just shown you the connections between the forces of supersensible knowledge and man's everyday existence. Something similar, though, can be said about the forces of man's normal nature, man's nature as it appears in ordinary life. Only there it is not so obvious. A very important force in ordinary life—and we have discussed it many times—is the force of memory. The power of memory is active within us when, as we say, we remember something we have experienced. But, as you all know, there is something peculiar about the power of memory. We have got it and yet we haven't got it. Many a person struggles at some moment of his life to try and remember something that he cannot remember. This wanting to remember but not being able to remember entirely, arises through the fact that the force we use in our souls to remember with is the same force that transforms the food we eat into the kind of substances our body can make use of. If you eat a piece of bread and this bread is transformed inside your body into the sort of substance that serves life, this is apparently a physical process. This physical process, however, is governed by supersensible forces. These supersensible forces are the same forces you use when you remember. So the same kind of forces are being used on the one hand for memory and on the other hand for the assimilation of foodstuffs in the human body. And you actually always have to oscillate a bit between your soul and your body if you want to dwell in memory. If your body is carrying out the process of digesting too well, you may find you will not be able to draw enough forces away from it to remember certain things. There is an inner struggle going on the whole time in the unconscious between a soul process and a bodily process every time you want to remember something. Looking at memory is the best way to understand how absurd it is basically, from a higher point of view, for some people to be idealists and other people materialists. The assimilation of foodstuffs in the human body is doubtless a material process. The forces controlling it are the same as the forces at work in a process of ideas, namely the force of memory. You only see the world aright if you see it as being neither materialistic nor idealistic, but are capable of following up the ideal aspect of what is presented in a material way and following up the material aspect of what is presented as idea. The spiritual quality of a world conception is hot being able to say 'Over there is base materialism, which is for the 'dregs' of humanity, and over here is idealism, which is for the elect—and the speaker usually includes himself among these—but the essential quality of a really spiritual world conception lies in its capacity to take what it has grasped in the spirit and bring it down into material existence so that material existence can be understood and not despised. That is the fallacy of many religious denominations, that they despise material existence instead of understanding it and looking for the spirit within it. The crux of the matter is really to go into these things, and not, as is still largely the case, to deal in empty phrases where mysticism is concerned. After having as it were shown you how these things can really be gone into, I would now like to bring something of very great importance. When people speak of material existence and supersensible existence they usually speak of them as though material existence were spread out in the world and as though supersensible, non-perceptible existence were somewhere behind or above this. If you imagine you simply have physical-perceptible existence on the one hand and supersensible existence on the other, you will never understand man. There is no way of really grasping man if you look at things from the point of view of the perceptible world versus the supersensible world. In reality it is like this: The world of the senses and the world in which we work and live socially are spread out around us. Let us represent diagrammatically by means of this line this world that is spread out around us (see horizontal line of drawing). You will only have a complete picture of what is actually there in the world if you imagine that there are forces above this line, supersensible forces (red side). We neither perceive these supersensible forces by means of our ordinary senses nor by means of our intellect bound to our ordinary senses. We perceive only what is in the realm of this line.  But there are forces under this line as well. If we actually want to include the whole of the imperceptible or spiritual realm we must speak of subsensible as well as supersensible forces. So we must imagine that there are also subsensible forces here (orange side). Thus we have the sense world, supersensible forces and subsensible forces. Where does man himself, as an ordinary person, belong? The part of him you see standing in front of you belongs entirely to this line. But supersensible forces from one side and subsensible forces from the other side work into the part of man that belongs to the line. Man is the result of supersensible and subsensible forces. Now which of man's forces are supersensible and which are subsensible? All the forces connected with understanding are supersensible, that is, everything we make use of for understanding. And these are the same forces that also form our head. So we can say that the supersensible forces are the forces of understanding. Now subsensible forces also work into man. What kind of forces are these? These are will forces. All the will forces, everything in man that is of the nature of will, is subsensible. An obvious question is where do these subsensible forces, these will forces, come from? They are the same forces as the forces of the planets, that is, from our point of view, the forces of the earth. Yes indeed, the forces of the earth are perpetually working into man. And it is our forces of will that are connected with these forces of the planets, these forces of the earth. The forces of understanding come to us from the world's periphery, and pour into us as it were from outside, from the outside of the planet. The forces of will enter into us from the planet itself. This is how the forces of our own planet earth live within us. The moment we enter birth the forces of planet earth are active within us. The question now arises as to how this activity is distributed. There is a considerable difference in this respect in the first, second and third stage of life, that is, up till the seventh year, the fourteenth year and the twenty-first year. The will working in us up till the seventh year works entirely from out of the planet's interior. It is very interesting to see spiritual-scientifically that in everything working in the child up till the age of seven it is the forces of the earth's depths that are active. If you want to see an actual manifestation of the forces of the earth's interior, then make a study of everything going on in the child up till the age of seven, for these are the forces from within the earth. To delve down into the earth to find the forces of the earth's interior would be absolutely wrong. You would only find earth substances. The forces that are active in the earth come to manifestation in the work they do in the human being up till his seventh year. And from the seventh to the fourteenth year it is the forces of the encircling air that work in man, forces that still belong to the earth, to the earth's atmosphere. These are predominantly at work in everything developing in the human being between seven and fourteen. Then comes the most important stage of all, from fourteen to twenty-one. At this stage the subsensible passes over into the supersensible. Here a kind of balance is created between the subsensible and supersensible. Now the forces of the earth's whole solar system work at organising the human being. So we have the earth's interior in the first period of life; encircling air in the second period of life, that is, what the earth itself is embedded in. The forces streaming down from cosmic spaces in so far as these cosmic spaces are filled with our own actual planetary system, up till the twenty-first year. Not until the age of twenty-one does man tear himself away, as it were, from the influences brought about in him from outside by the planets and the planetary system belonging to these. Please notice that in everything I have referred to as having an influence on man, bodily influences are of course included. They are bodily processes that the forces from the planet's interior bring about up till the seventh year. They are bodily processes that are formed by the circulating air in connection with the breathing and so on between the seventh and the fourteenth year. There is no doubt that they are bodily processes, in fact actual transformations of bodily organs are brought about; everything being connected with man's growing and becoming larger. Thus man grows beyond all this work being done on him by the earth; all this ceases at twenty-one. What happens then, however? What happens after twenty-one? Up till twenty-one we draw on what comes from the earth and its planetary system in the way we have described. We build up our constitution with the earth's help. Then, after we have reached the age of twenty-one, we have to draw on ourselves. We gradually have to release what we have put into our organism from out of the forces of the planet and the planetary system. Activities going on in the blood forces always used to ensure that this happened in the past. As you will probably know, man has not learnt to release the planetary forces, himself, after the age of twenty-one. And yet he has been doing so. He did it as an unconscious process. The capacity was in his blood. It was built into him to do it. The important change in our present time—and the present extends over a long period of several centuries, of course—is that man's blood is losing the capacity to release what we have put into the organism in this way, before twenty-one The important changes taking place in humanity at the present time are based on the waning of the forces in the blood. These things cannot be testified by external anatomy and physiology; to do that they would need to investigate bodies from the tenth or ninth centuries in order to discover that blood was different then. And they would not even have had the chemical tests to do it. But through spiritual science we can know with certainty that man's blood has grown weaker. And the great turning-point when human blood began to grow weak lay in the middle of the fifteenth century. What are the consequences? The consequences of this are that what we cannot carry out unconsciously any more by means of our blood, we have to carry out consciously. We have to educate ourselves to do consciously what was simply done unconsciously by man's blood in the past. For the strength in our blood is in the process of fading away. What would happen if a time were to come when human beings completely lost hold of their youth, and were unable to draw on their youthful forces, if there were no means of resorting to doing consciously what was once done unconsciously by the blood? You must not take these things in a purely theoretical way, of course. As theories, they may be interesting, but to take them as theories is not enough. Nowadays they have to be put into practice, for they are connected with the practical matter of the evolution of mankind. They must be put into practice to the point of making us conscious that man's whole educational system has to change. We have to help man to develop a strong, conscious capacity to re-experience later in life, as though with the force of elemental memory, what he has received in his youth. Everywhere, people are still working contrary to this requirement. For instance they are proud of the visual aids used in primary school education, and they attach great importance to getting down to the mental level of the child as far as possible, and not teaching him anything that extends beyond his mental capacity. They actually rig up calculating machines so that they can teach the children to do all kinds of sums by counting balls. Nothing must go beyond the child's mental capacity. These visual aid lessons get frightfully trivial and trite. It is bound to lead to nothing but commonplace concepts if they avoid giving the child anything beyond its own mental capacity. People who do this, thoroughly overlook an important yet subtle observation of human life. Supposing a child is taught in such a way that he takes a particular thing in, not because it is absolutely on his own mental level, but because his teacher's warmth of enthusiasm gets passed on to him, and the child takes the thing in because the teacher in his enthusiasm tells him about it. The child takes it in just because it lives in the warmth emanating from the teacher. If the child absorbs something that reaches beyond his understanding, purely because of the infectious quality of his teacher's enthusiasm, he will not yet understand what he has taken in, as people say in superficial life. Yet what he has taken in lives in his soul. At the age of thirty the grown-up will remember what the child took in, perhaps at the age of ten. He re-experiences it. He has become mature now, and he can understand what he is able to release from the depths of his soul; he can understand the thing he was taught purely through the force of enthusiasm, and which he is now able to release from his mature mind. You know, these are the most valuable moments in life, when your mental life does not have to be restricted to what comes to meet you from outside, but you re-experience what you took in in your younger days with inadequate understanding, and which you can now release and absorb with your more mature mind. The more care you take that the child does not just get the sort of lessons where it matter-of-factly takes in what it understands—for that will disappear with the passing years, and neither joy nor enthusiasm will come from it later—the more you will be doing for the person's later development; for lessons taken in purely through the teacher's warmth are life giving when they are re-experienced. Nowadays this is of particular importance in teaching- In earlier times it was not so important, for in those days the releasing was carried out by the blood, whereas now it has to be brought to consciousness. It certainly makes a difference if you understand the kind of things that are being put to practical use by spiritual science. Because if you understand them in the right way you will find an opportunity somewhere in life of making practical use of them for the good of humanity. In this case, if you understand it properly, you will find an opportunity to make use of the fact that our blood is becoming weak, by attaching all the more importance to the teacher's capacity for enthusiasm. But people are so little aware nowadays of what is at stake. For standardised education still plays a great part, that is, the kind of education that works with a whole set of standard rules. Education is learnt, how to teach a child is learnt, how to arrange the lesson is learnt. Comparing this with our present day consciousness it would be like learning that man consists of carbohydrates, protein and so on—these are our constituents and they undergo such and such changes inside our body, and we cannot eat before we have understood this; for we do not eat in a physiological sense until we understand it.—I told you once, and you may even have experienced this yourselves—, that you can already come across a thing like this:—You visit someone who has a scale standing beside his plate, and he carefully puts a piece of meat on the scales to find out how much it weighs, for he may only eat a piece of meat of a quite specific weight. Physiology already determines his appetite. But not everybody does it this way yet, thank goodness! It is important to understand that physiology is not part of the eating process but covers other aspects, and that a person can eat without having studied physiology, the physiology of the nutritional process. But we do not take it for granted that we also ought to teach, that is, teach in a living way, without having absorbed standardised education. This standardised education is exactly the same thing to a good teacher as the aesthetics of colour is to an artist. He can have studied aesthetics of colour very well, but he will not be able to paint because of that. The ability to paint comes from an entirely different quarter from the study of the aesthetics of colour. The ability to teach comes from an entirely different quarter from the study of education. The important thing, today, is not to give would-be teachers a seminar of some sort of standardised education that prescribes dogmas, but to give them the sort of thing that makes them become teachers and educators in the same way as people become artists or botanists. It is that the educator has to be born in a person and not that education has to be learnt. What has to be understood just because of this very change in man's set-up is that education has to be a real art. In the time of transition people were at sixes and sevens as to what to do about education. That is why they invented so many abstract educational systems. The essential thing today, however, is to give people a real knowledge of man, especially if they are teachers. You see, if you possess this real knowledge of man and work out of it with children, a remarkable thing will happen: Let us suppose you are a teacher and have your pupils in front of you. If you are a student of standardised education, the kind that follows the rules, then you will know exactly how you have to teach, because you will have learnt the rules. You will teach according to these rules, today, just as you taught according to these rules yesterday and will teach according to them tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. But if you are the artist kind of teacher you are not nearly so well off. For now you cannot teach yesterday, today, tomorrow and the day after tomorrow according to the same rules, but have to learn from the child afresh each time, how he has to be taught; it must be man's own nature every time that determines what you do. And it is ideal if the teacher can teach the way the child tells him to teach, and can keep on forgetting actual education and has not got a clue about the rules. For the moment the child stands in front of him again he will again be electrified by the growing child and will know what he has to do with him. You must pay attention to the way things have to be said, to the way things have to be spoken about today. You cannot speak about these things today in such a way that they can be put into so and so many satisfying principles, but you can only speak about them by pointing to something alive, something that cannot be reduced to abstract principles but which is alive and produces ever more life. That is the crux of the matter. That is why spiritual science is needed in actual life today, because spiritual science is not merely for the head but is for the whole of man and releases will impulses. Indeed it ought to enter into many realms of life, so that impulses of will are eventually brought into every sphere of human activity. I have demonstrated this in one particular realm of life, namely education, and shown how the education of children under the age of twenty-one can be made to bear fruit for later life. People do not receive an education only up to the age of twenty-one, though, for education carries on throughout the whole of life. But this only happens in a healthy way if people learn from one another. This too was done by the blood in earlier ages of history. When people met in social life they used to learn things from one another unconsciously, some people learning more and others less, according to the way their blood worked. But our blood has grown weak and has lost its power. This activity, too, has to be replaced by more consciousness. People must achieve the art of acquiring relatively more for themselves from other people compared with what they produce from out of themselves. In earlier times it was sufficient to rely on life. The blood did everything. Now it is essential for people really to develop a sense for the other person's being. This will come about as a matter of course if people steer their thoughts in the direction of spiritual science. Different kinds of thoughts are stimulated with spiritual science than without it. You will not doubt this fact, for the way spiritual science is received by people who do not want to know anything about their thoughts shows that spiritual scientific thoughts are different from thoughts without spiritual science. It is necessary to develop a totally new way of thinking. The kind of thinking we develop when we accustom ourselves to working with supersensible thoughts is the kind of thinking that has an effect on our organism. And when I told you today that memory is the same force that transforms food into substances man needs for his organism you will no longer be astonished to find that other forces can be transformed in man, like for instance the force with which we understand supersensible things being the same one that helps us to know the human being better than we would know him if we had no healthy longing for supersensible knowledge. You people study what is in my Occult Science, and to do that you have to develop certain concepts that most people would still call 'Utter madness'. A few days ago I got yet another letter from someone studying Occult Science, and he says that nearly every chapter is pure nonsense. You can understand people saying it is pure nonsense. Why, it is quite obvious that they often say it these days. Yet these people who do not put themselves out to accept the kind of concepts that lead to Saturn, Sun, Moon, Jupiter, Venus and Vulcan, and do not get down to developing ideas about a world that is not limited to the senses will also not acquire any knowledge of man. They do not see the human being in the other person but notice at the most that one person has a more pointed nose than the other, and one has blue eyes whereas the other has brown. But they notice nothing of man's inner being that manifests as his soul and organises his body. The same force which enables us to take an interest, and I am not saying now that it enables us to have supersensible occult powers, but the same force that enables us to take an interest in supersensible knowledge also gives us the kind of knowledge of man that we need today. You can set up the most grandiose social programmes and develop the finest social ideas, but if people shy away from acquiring any knowledge of man and do not see any real humanity in one another, they will never be able to bring about social conditions. They cannot produce social conditions unless they establish the possibility that people can be social. But people cannot be social if they do not see the human quality in one another, but live entirely within themselves. Human beings can only become social if they really meet one another in life, and something passes between them. This is the root of the social problem. Most people say of the social question nowadays, that if certain things were arranged in such and such a way people would be able to lead a social existence.—But it is not like that. If things are arranged like that, social people will be good people in a social sense, and anti-social people will be anti-social with any sort of arrangement. The essential thing is to make the sort of arrangements that allow for human beings to develop really social impulses. And one of these social impulses is knowledge. But as long as you go on educating people, for instance, with an eye to their becoming clerks or army officers or some other kind of civil servant, you will not educate them to recognise the human quality in others. For the sort of education that is good for becoming a clerk or an officer only helps you to see clerks and officers in other people. The kind of education that makes human beings of people also enables them to recognise people as human beings. But it is impossible to recognise people as human beings if you do not develop a sense for supersensible knowledge. And the realm in which supersensible knowledge is most indispensable is in the art of education. Therefore the natural scientific, materialistic way of thinking has done more damage in the field of education than anywhere else. And here you can experience the most amazing things. In every department you find well-meaning people today, who want to reform everything, even revolutionise them. But if you talk to these people about these things, something very strange transpires. They will admit quite honestly to a particular conviction about reforming things. Yet one of them who happens to be a tailor will ask you how his existence as a tailor is going to be affected when things change. And another person, who is, let us say, a railway clerk, asks you how his life as a railway clerk is going to suffer when things are changed.—These are only given as examples to show you that people are perfectly in agreement that everything should be changed as long as nothing changes and everything remains exactly the same. The vast majority of people today are convinced that everything must stay exactly the same when it changes. Make no mistake about the fact that the sort of social improvement people long for today is of extremely abstract dimensions. People long for a great deal, but nothing must change where their comfort is concerned. And this is particularly true where it is a of people taking an inner step into an entirely new situation. Nevertheless the essential thing is that people open themseIves to the possibility of making the transition to thinking in quite a new way about man changing himself in his innermost being. All sorts of questions arise from these considerations, questions that are absolutely pertinent to life. What we must realise is that we have constructed a deeper foundation for these questions, by saying that although certain forces appear to be of a spiritual-soul nature, they also come to expression in our bodily nature. For the capacity is terribly lacking today, to bring down to a material level what we think of on a spiritual level. Not until we are capable of bringing down on to a material level what we think of as being spiritual shall we be able to grasp the actual nerve of the social question. Thus it is virtually a matter of aiming towards a way of thinking that really develops a knowledge of man that is at one and the same time a social impulse. A way of thinking based on anything else is not adequate. A mentality based on the life of the state or the life of economics creates clerks and officers. But the sort of mentality we need creates human beings. This can only be the sort of thought life that breaks away from the sphere of economics and the life of the state. That is why our Threefold Social Organism had to happen. We had to show in a radical way that any kind of dependency of thought life on economics or on the life of the state had to stop, and thought life had to be set up on its own basis. Then thought life will be able to give economics and the life of the state what economics and the state cannot give to the life of thought. That is the important thing, that is what is vital! Whole human beings will only arise again when we work out of an independent life of thought. |

| 220. Man's Fall and Redemption

26 Jan 1923, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Were they to speak of the true nature of thinking; not of its corpse, they would realise the necessity of considering man's inner life. There they would discover that the force of thinking, which becomes active when a human being is born or conceived, is not complete in itself and independent, because this inner activity of thought is the continuation of the living force of a pre-earthly thinking. |

| By forming it in beauty. Even in Plato's definitions we can feel what the Greek meant when he wished to form the human being artistically. |

| But when we ask in the Greek sense: what is a beautiful human being? this does indeed signify something. A beautiful human being is one whose human shape is idealised to such an extent that it resembles a god. |

| 220. Man's Fall and Redemption

26 Jan 1923, Dornach Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|