The Fourth Dimension

GA 324a

24 May 1905, Berlin

Translated by Steiner Online Library

Fourth Lecture

I recently tried to give you a schematic idea of four-dimensional space. But it would be very difficult if we were not able to form a picture of four-dimensional space in some kind of analogy. If it were a matter of characterizing our task, then it would be this: to show a four-dimensional structure here in three-dimensional space. Initially, we only have three-dimensional space at our disposal. If we want to link something unknown to us with something known, then, just as we have mapped a three-dimensional object into two dimensions, we have to bring a four-dimensional object into the third dimension. Now I would like to show, in the most popular way possible, using Mr. Hinton's method, how four-dimensional space can be mapped within three dimensions. So I would like to show how this task can be solved.

First, let me assume how to bring three-dimensional space into two-dimensional space. Our blackboard here is a two-dimensional space. If we were to add depth to height and width, we would have three-dimensional space. Now let's try to visualize a three-dimensional object on the blackboard.

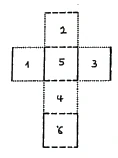

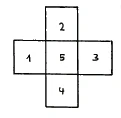

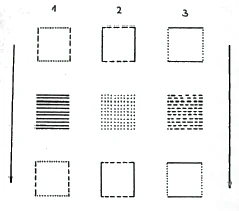

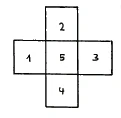

A cube is a three-dimensional object because it has height, width and depth. Let's try to bring it into two-dimensional space, or onto a plane. If you take the whole cube and roll it up, or rather unroll it, you can do it like this. The sides, the six squares that we have in three-dimensional space, can be spread out once in a plane (Figure 25). So I could imagine the boundary surfaces of the cube spread out on a plane in a cross shape.

There are six squares that can be rearranged to form a cube again if I fold them back, so that squares 1 and 3, 2 and 4, and 5 and 6 are opposite each other. Thus we have a three-dimensional structure simply laid in the plane.

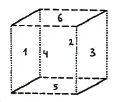

This is not a method that we can use directly to draw the fourth dimension in three-dimensional space. For that, we have to look for a different analogy. We have to use colors to help us. To do that, I will label the six squares along their sides with different colors. The squares facing each other [in the cube] should have the same colors when they are unfolded. I will draw the squares 1 and 3 so that one side is red [dotted lines] and the other is blue [solid lines]. Now I will complete these squares so that I keep blue for the whole horizontal direction (Figure 26). So I will draw all the vertical sides of these squares in red and all the horizontal sides in blue.

If you look at these two squares, 1 and 3, you have the two dimensions that the squares have, expressed in two colors, red and blue. So here for us [at the vertical blackboard, where square 2 is “stuck” to the blackboard], red would mean height and blue depth.

Let us now keep in mind that we apply red wherever height occurs and blue wherever depth occurs; and then we want to take green [dashed line] for the third dimension, width. Now we want to complete the unfolded cube in this way. The square 5 has sides that are blue and green, so the square 6 must look the same. Now only the squares 2 and 4 remain, and if you imagine them unfolded, it follows that the sides will be red and green.

Now, if you imagine it, you will see that we have transformed the three dimensions into three colors. We now say red [dotted], green [dashed], and blue [(solid line)] for height, width, and depth. We name the three colors that are to be images for us instead of the three spatial dimensions. If you imagine the whole cube opened up, you can explain the third dimension in two dimensions in such a way as if, for example, you had let the blue-red square [from left to right in Figure 26] march through green. We want to say that red and blue passed through green. We will describe the marching through green, the disappearance into the third color dimension, as the passage through the third dimension. So, if you imagine that the green fog colors the red-blue square, both sides – red and blue – will appear colored. Blue will take on a blue-green hue and red a cloudy shade, and only where the green stops will both appear in their own color again. I could do the same with squares 2 and 4. So I let the red-green square move through a space that is blue, and then you can do the same with the other two squares, 5 and 6, where the blue-green square would have to pass through the red. In this way, you let each square disappear on one side, submerging it in a different color. It takes on a different color itself through this third color, until it emerges on the other side in its original state.

We thus have an allegorical representation of our cube using three perpendicular colors. We have simply used three colors to represent the three directions we are dealing with here. If we want to imagine the changes that the three pairs of squares have undergone, we can do so by imagining that the squares pass through green the first time, red the second time, and blue the third time.

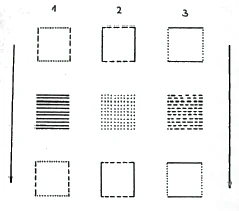

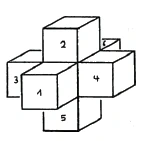

Now imagine squares instead of these [colored] lines, and squares everywhere for the bare space. Then I can draw the whole figure differently (Figure 27). We draw the transit square blue, and the two that pass through it – before and after the transit – we draw them above and below, here in red-green. [In a second step] I take the red square as the one that allows the blue-green squares to pass through it. And [in a third step] we have the green square here. The two corresponding other colors, red and blue, pass through the green square.

You see, now I have shown you another form of propagation with nine adjacent squares, but only six of which are on the cube itself, namely the squares drawn at the top and bottom of the figure (Figure 27). The other three [middle] squares are transition squares that denote nothing more than the disappearance of the individual colors into a third [color]. [For the transition movement, we] therefore always have to take two dimensions together, because each of these squares [in the upper and lower rows] is composed of two colors and disappears into the color that it does not contain itself. To make these squares reappear on the other side, we let them disappear into the third color. Red and blue disappear into green, red and green have no blue, so they disappear into blue [and green and blue disappear into red].

So, you see, we have the option here of assembling our cube using squares from two color dimensions that pass through the third color dimension.

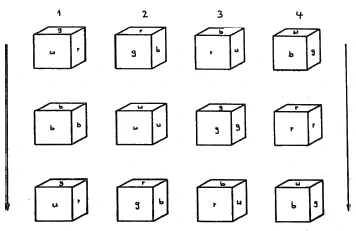

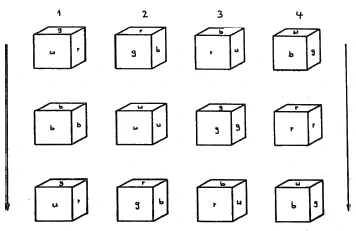

Now it stands to reason that we imagine cubes instead of squares, and in doing so we put the cubes together out of three color dimensions – just as we put the square together out of two lines of different colors – so that we have three colors, according to the three dimensions of space. If we now want to do the same as we did with the square, we have to add a fourth color. This will allow us to make the cube disappear as well, of course only through a color that it does not have itself. Instead of the three pass squares, we now have four pass cubes in four colors: blue, white, green, and red. So instead of the pass square, we have the pass cube. Mr. Schouten has now produced these colored cubes in his models.

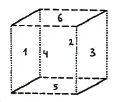

Now, just as we have a square pass through another that is not its color, we must now let a cube pass through another that is not its color. So we let the white-red-green cube pass through a blue one. It will submerge into the fourth color on one side and reappear in its [original] colors on the other side (Figure 28.1).

So here we have a [color] dimension bounded by two cubes that have three colored faces. In the same way, we now have to let the green-blue-red cube pass through the white cube (Figure 28.2), and then let the blue-white-red cube pass through the green (Figure 28.3). In the last figure (Figure 28.4), we have a blue-green-white cube that has to pass through a red dimension, that is, it has to disappear into a color that it does not itself have, in order to reappear on the other side in its very own colors.

These four cubes behave exactly like our three squares did before. If you now realize that we need six squares to bound a cube, we need eight cubes to bound a four-dimensional object, the tessaract.

Just as we obtained three auxiliary squares there, which only signify their disappearance through the other dimension, so here we obtain twelve cubes in all, which are related to each other in the same way that these nine figures are related in the plane. Then we did the same with the cube as we did earlier with the squares, and by choosing a new color each time, a new dimension was added to the others. So we think, we represent a body that has four dimensions in color, in that we have four different colors in four directions, with each [single] cube having three colors and passing through the fourth [color].The purpose of this substitution of dimensions with colors is that, as long as we stick with the [three] dimensions, we cannot bring the three dimensions into the [two-dimensional] plane. But if we use three colors instead, we can do it. We do the same with four dimensions if we want to visualize them using [four] colors in three-dimensional space. This is one way in which I would like to introduce you to these otherwise complicated things, and how Hinton used them in his problem [of the three-dimensional representation of four-dimensional structures].

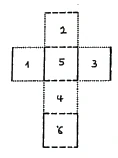

I would now like to spread out the cube in the plane again, to turn it over into the plane once more. I will draw this on the board. First, disregard the bottom square [of Figure 25] and imagine that you can only see two-dimensionally, so you can only see what is spread out on the surface of the board. If we put five squares together as in this case, so that they are arranged in such a way that the one square comes into the middle, this inner area remains invisible (Figure 29). You can go around it from all sides. You cannot see square 5 because you can only see in two dimensions.

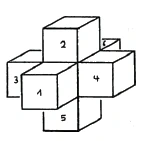

Now let us do the same thing that we have done here with five of the six side squares of the cube with seven of the eight boundary cubes that form the tessaract when we spread our four-dimensional structure into space. I will lay out the seven cubes in the same way as I did with the faces of the cube on the board; only now we have cubes where we previously had squares. Now we have here the corresponding spatial figure, formed entirely analogously. Thus we have the same for three-dimensional space as we previously had for two-dimensional surface. Just as a square is completely hidden from all sides, so is the seventh cube, which a being that has [only] the ability to see three-dimensionally will never be able to see (Figure 30). If we could fold up these figures in the same way as the six unfolded squares of the cube, we could pass from the third into the fourth dimension. We have shown how one can form an idea of this by means of color transitions."

With this, we have at least shown how, despite the fact that humans can only perceive three dimensions, we can still imagine four-dimensional space. Now you might still wonder how one can gain a possible conception of the real four-dimensional space. And here I would like to point you to something that is called the actual “alchemical secret.” For the real insight into four-dimensional space is in some way connected with what the alchemists called “transformation”.

[First variant:] He who wishes to acquire a true intuitive grasp of four-dimensional space must perform very definite exercises in intuitive grasp. These consist in his first forming a very clear intuitive perception, a deepened intuitive perception, not an imagination, of what is called water. Such an intuitive perception of water is not so easy to come by. One must meditate for a long time and delve very deeply into the nature of water; one must, so to speak, creep into the nature of water. The second thing is to gain an insight into the nature of light. Man is familiar with light, but only in the sense that he receives it from outside. Now, through meditation, man comes to receive the inner counter-image of outer light, to know where and from what light arises, so that he can himself bring forth and generate something like light. The yogi acquires this ability to produce and generate light through meditation. This is possible for the person who is able to have pure concepts truly meditatively present in his soul, who truly allows pure concepts to have a meditative effect on his soul, who is able to think free of sensuality. Then the light arises from the concept. Then the whole environment opens up to him as flooding light. The secret disciple must now, as it were, chemically combine the conception he has formed of water with the conception of light. The water, completely permeated by light, is a body called by the alchemists Mercury. Water plus light is called Mercury in the language of the alchemists. But this alchemical Mercury is not ordinary mercury. You will not have received the matter in this form. One must first awaken within oneself the ability to generate the light from the [dealing with the pure] concepts. Mercury is this mixture [of light] with the contemplation of water, this light-imbued water power, in whose possession one then puts oneself. That is one element of the astral world.

The second [element] arises from the fact that, just as one has formed an idea of water, one forms an idea of air, that we therefore suck out the power of the air through a mental process. If you concentrate your feeling in a certain way, you create a fire through feeling. If you combine the power of the air chemically with the fire created by feeling, you get “fire air.” You know that Goethe's Faust speaks of fire air.” This is something in which the inner being of the person must participate. So one element is sucked out of a given element, the air, and the other [fire or warmth] is generated by yourself. This air plus fire was called sulfur, sulphur, luminous fire-air by the alchemists.

If you now have this luminous fire air in an aqueous element, then you truly have that [astral] matter of which it says in the Bible: “And the Spirit of God hovered, or brooded, over the ‘waters’.”

[The third element arises when] you draw the power from the earth and then connect it with the [spiritual forces in the] “sound”; then you have what is called the Spirit of God [here]. Therefore, it is also called “thunder”. [The acting] Spirit of God is thunder, is earth plus sound. The Spirit of God [thus hovers over the] astral matter.

Those “waters” are not ordinary water, but what is actually called astral matter. This consists of four types of forces: water, air, light and fire. The arrangement of these four forces presents itself to the astral view as the four dimensions of astral space. That is how they are in reality. It looks quite different in the astral than in our world, some things that are perceived as astral are only a projection of the astral into physical space.

You see, that which is astral is half subjective [that is, passively given to the subject], half water and air, because light and feeling [fire] are objective, [that is, actively brought to appearance by the subject]. Only part of what is astral can be found outside [given to the subject] and obtained from the environment. The other part must be brought about subjectively [through one's own activity]. Through conceptual and emotional powers, one gains the other [from the given] through [active] objectification. In the astral, we thus have subjective-objective elements.

In devachan, there is no longer any objectivity [that is merely given to the subject]. One would have a completely subjective element there.

When we speak of the astral realm, we have something that the human being must first create [out of himself]. So everything we do here is symbolic, an allegorical representation of the higher worlds, of the devachanic world, which are real in the way I have explained to you in these suggestions. What lies in these higher worlds can only be attained by developing new possibilities of perception within oneself. Man must do something himself for this.

[Second text variant (Vegelahn):] Those who want to acquire a real view of four-dimensional space must do very specific visual exercises. First of all, they form a very clear, in-depth view of water. Such a view is not easy to come by; one has to delve very deeply into the nature of water; one has to, so to speak, get into the water. The second thing is to gain an insight into the nature of light. Light is something that man knows, but only in the sense that he receives it from outside. Through meditation, he can gain an inner image of light, know where light comes from and therefore produce light himself. This can be done by someone who allows pure concepts to have a real meditative effect on his soul, who has a thinking free of sensuality. Then the whole of his environment will reveal itself to him as flooding light, and now he must, as it were chemically, combine the idea he has formed of water with that of light. This water, completely permeated by light, is a body that was called “Mercury” by the alchemists. But the alchemical Mercury is not the ordinary mercury. First you have to awaken within yourself the ability to generate Merkurius from the concept of light. Merkurius, light-imbued water power, is what you then place yourself in possession of. That is the one element of the astral world.

The second is created by you also forming a vivid mental image of air, then sucking out the power of the air through a spiritual process, connecting it with feeling, and you ignite the concept of “warmth”, “fire”, then you get “fire air”. So one element is sucked out, the other is produced by yourself. This - air and fire - the alchemists called “sulfur”, sulfur, luminous fire air. In the aqueous element, there you have in truth that matter of which it is said: “and the Spirit of God hovered over the waters”.

The third element is “spirit-God”, which is connected to “earth” and “sound”. This is what happens when you extract the earth's forces and combine them with sound. These “waters” are not ordinary water, but what is actually called astral matter. This consists of four types of forces: water, air, light and fire. And this manifests itself as the four dimensions of astral space.

You see, that which is astral is half subjective; only part of what is astral can be gained from the environment; from conceptual and emotional powers, one gains the other through objectification. In devachan, you would have a completely subjective element; there is no objectivity there. So everything we do here, the symbolic, is an allegorical representation of the devachanic world. Everything that lies in the higher worlds can only be attained by developing new views within yourself. Man must do something about it himself.

Vierter Vortrag

Ich versuchte neulich, schematisch Ihnen eine Vorstellung vom vierdimensionalen Raum zu geben. Es würde dies aber sehr schwer sein, wenn wir nicht in einer Art von Analogie uns ein Bild von dem vierdimensionalen Raum zu machen in der Lage wären. Wenn es sich darum handelte, unsere Aufgabe zu charakterisieren, so würde es dies sein: ein vierdimensionales Gebilde aufzuzeigen hier im dreidimensionalen Raum. Zunächst steht uns ja nur der dreidimensionale Raum zur Verfügung. Wollen wir sozusagen etwas, was uns unbekannt ist, anknüpfen an etwas Bekanntes, so müssen wir uns, ebenso wie wir uns ein Dreidimensionales ins Zweidimensionale abgebildet haben, ein Vierdimensionales hereinholen in die dritte Dimension. Nun möchte ich an der Methode des Herrn Hinton möglichst populär zeigen, wie der vierdimensionale Raum innerhalb der drei Dimensionen abzubilden ist. Ich möchte also zeigen, wie diese Aufgabe gelöst werden kann.

Zunächst lassen Sie mich davon ausgehen, wie man den dreidimensionalen Raum in den zweidimensionalen Raum hineinbringt. Unsere Tafel hier ist ein zweidimensionaler Raum. Würden wir zur Höhe und Breite eine Tiefe hinzunehmen, so hätten wir den dreidimensionalen Raum zusammen. Nun wollen wir versuchen, uns ein dreidimensionales Gebilde anschaulich auf der Tafel abzubilden.

Der Würfel ist ein dreidimensionales Gebilde, weil er aus Höhe, Breite und Tiefe besteht. Versuchen wir, ihn in den zweidimensionalen Raum zu bringen, also auf die Ebene. Wenn Sie den ganzen Würfel nehmen und ihn abrollen, oder besser abwickeln, so können Sie das auf folgende Art machen. Die Seiten, die sechs Quadrate, die wir im dreidimensionalen Raum haben, können wir einmal ausbreiten in einer Ebene (Figur 25). So könnte ich mir also die Begrenzungsflächen des Würfels auf der Ebene ausgebreitet denken in einer Kreuzesfigur.

Es sind sechs Quadrate, die sich wieder zum Würfel ergänzen, wenn ich sie wieder zurückklappe, — so also, daß Quadrat 1 und 3, 2 und 4, und ebenso 5 und 6 einander gegenüberstehend sind. So haben wir ein dreidimensionales Gebilde einfach hineingelegt in die Ebene.

Das ist eine Methode, die wir so nicht unmittelbar gebrauchen können, um die vierte Dimension in den dreidimensionalen Raum zu zeichnen. Dafür müssen wir eine andere Analogie suchen. Wir müssen da Farben zu Hilfe nehmen. Dazu werde ich die sechs Quadrate ihren Seiten nach mit verschiedenen Farben bezeichnen. Die einander [im Würfel] gegenüberliegenden Quadrate, wenn sie aufgeklappt sind, sollen gleiche Farben haben. Ich werde die Quadrate 1 und 3 so zeichnen, daß die einen Seiten rot [punktierte Linien] und die anderen blau [durchgezogene Linien] sind. Nun werde ich mal diese Quadrate so ergänzen, daß ich Blau für die ganze horizontale Richtung beibehalte (Figur 26). Ich werde also alle diejenigen Seiten, die in diesen Quadraten vertikal sind, rot zeichnen, und alle horizontalen blau machen.

Wenn Sie sich diese zwei Quadrate 1 und 3 ansehen, so haben Sie die zwei Dimensionen, die die Quadrate haben, in zwei Farben, Rot und Blau, ausgedrückt. So würde also hier für uns [an der senkrechten Tafel, wo das Quadrat 2 an der Tafel «klebt»] Rot die Höhe und Blau die Tiefe bedeuten.

Halten wir nun das fest, daß wir überall, wo die Höhe auftritt, Rot anwenden, und dort, wo die Tiefe auftritt, Blau; und dann wollen wir für die dritte Dimension, die Breite, Grün [gestrichelte Linie] nehmen. Nun wollen wir uns in dieser Weise den auseinandergeklappten Würfel ergänzen. Das Quadrat 5 hat Seiten, welche blau und grün sind, also muß das Quadrat 6 ebenso aussehen. Nun bleiben noch die Quadrate 2 und 4 übrig, und wenn Sie sich die aufgeklappt denken, so ergibt sich, daß die Seiten rot und grün sein werden.

Nun sehen Sie, wenn Sie sich das einmal vergegenwärtigen, so haben wir die drei Dimensionen in drei Farben verwandelt. Für Höhe, Breite, Tiefe sagen wir jetzt Rot [punktiert], Grün [gestrichelt], Blau [(durchgezogen]. Wir nennen an Stelle der drei Raumdimensionen die drei Farben, die uns also dafür Bilder sein sollen. Wenn Sie sich den ganzen Würfel aufgeklappt denken, so können Sie sich zu zwei Dimensionen die dritte in der Weise erklären, als hätten Sie so zum Beispiel das blau-rote Quadrat [etwa von links nach rechts in Figur 26] durch Grün durchmarschieren lassen. Wir wollen sagen, Rot und Blau seien durch Grün hindurchgegangen. Das Durchmarschieren durch Grün, das Verschwinden in der dritten Farbendimension, wollen wir bezeichnen als den Durchgang durch die dritte Dimension. Denken Sie sich also, der grüne Nebel färbe dabei das rot-blaue Quadrat, so werden beide Seiten — rot wie blau — gefärbt erscheinen. Blau wird ein Blaugrün und Rot eine trübe Schattierung annehmen, und erst dort, wo das Grün aufhört, werden beide wieder in ihrer eigenen Farbe erscheinen. Dasselbe könnte ich mit den Quadraten 2 und 4 machen. Ich ließe also das rot-grüne Quadrat sich durch einen Raum bewegen, der blau ist, und dasselbe können Sie dann mit den beiden anderen Quadraten 5 und 6 vornehmen, wo das blau-grüne Quadrat das Rot passieren müßte. Ein jedes Quadrat lassen Sie auf diese Art auf der einen Seite verschwinden, in eine andere Farbe untertauchen. Es nimmt durch diese dritte Farbe selbst eine andere Färbung an, bis es auf der anderen Seite wieder in seiner Ursprünglichkeit heraustritt.

Wir haben so eine sinnbildliche Darstellung unseres Würfels durch drei aufeinander senkrecht stehende Farben. Wir haben durch drei Farben einfach die drei Richtungen dargestellt, mit denen wir es hier zu tun haben. Wenn wir uns vorstellen wollen, welche Veränderung die drei Paare der Quadrate erlitten haben, so können wir es dadurch, daß einmal die Quadrate durchgehen durch das Grün, das zweite Mal gehen sie durch das Rot, und das dritte Mal durch das Blau durch.

Nun denken Sie sich statt dieser [gefärbten] Linien einmal selbst Quadrate und für den bloßen Raum auch überall selbst Quadrate. Dann kann ich die ganze Figur noch anders zeichnen (Figur 27). Wir zeichnen uns das Durchgangsquadrat blau, und die beiden, welche durchgehen — vor und nach dem Durchgang —, zeichnen wir oben und unten daneben, also hier rot-grün. [In einem zweiten Schritt] nehme ich das rote Quadrat als dasjenige, welches die blau-grünen Quadrate durch sich hindurchgehen läßt. Und [in einem dritten Schritt] haben wir hier das grüne Quadrat. Durch das grüne Quadrat gehen die zwei entsprechenden anderen Farben durch, also Rot und Blau.

Sie sehen, jetzt habe ich Ihnen hier eine andere Form der Ausbreitung gezeigt mit neun nebeneinanderliegenden Quadraten, wovon aber nur sechs [Begrenzungen] am Würfel selbst sind, nämlich die oben und unten in der Figur gezeichneten Quadrate (Figur 27). Die anderen drei [mittleren] Quadrate sind Durchgangsquadrate, die nichts anderes bezeichnen, als das Verschwinden der einzelnen Farben in einer dritten [Farbe]. [Für die Durchgangsbewegung haben wir] also immer zwei Dimensionen zusammenzunehmen, weil jedes dieser Quadrate [in der oberen und unteren Reihe] aus zwei Farben zusammengesetzt ist und in der Farbe verschwindet, die es nicht selbst enthält. Damit diese Quadrate [jeweils wieder] auf der anderen Seite erscheinen, lassen wir sie also in der dritten Farbe verschwinden. Rot und Blau verschwinden durch Grün, Rot und Grün haben kein Blau, verschwinden also durch Blau [und Grün und Blau verschwinden durch Rot].

So also, sehen Sie, haben wir hier die Möglichkeit, unseren Würfel durch Quadrate aus zwei Farbendimensionen zusammenzusetzen, die durch die dritte Farbendimension hindurchgehen.”

Nun liegt es nahe, daß wir uns statt der Quadrate Würfel vorstellen und setzen dabei die Würfel aus drei Farbendimensionen zusammen — ebenso wie wir das Quadrat aus zweierlei gefärbten Linien zusammengesetzt haben —, so daß wir drei Farben haben, nach den drei Dimensionen des Raumes. Wollen wir nun dasselbe machen, was wir beim Quadrat gemacht haben, so müssen wir eine vierte Farbe hinzunehmen. Dadurch werden wir den Würfel ebenso verschwinden lassen [können], natürlich nur durch eine Farbe, die er nicht selbst hat. — Statt der drei Durchgangsquadrate haben wir nun einfach vier Durchgangswürfel aus vier Farben: Blau, Weiß, Grün und Rot. Also statt des Durchgangsquadrates haben wir den Durchgangswürfel. Herr Schouten hat nun in seinen Modellen diese farbigen Würfel hergestellt.

Nun müssen wir, wie wir hier ein Quadrat durch ein anderes gehen ließen, das nicht seine Farbe hat, so müssen wir jetzt einen Würfel durch einen anderen durchgehen lassen, der seine Farbe nicht hat. Wir lassen also den weiß-rot-grünen Würfel durch einen blauen hindurchgehen. Er wird auf der einen Seite in die vierte Farbe untertauchen und auf der anderen Seite wieder in seinen [ursprünglichen] Farben erscheinen (Figur 28.1).

So haben wir hier eine [Farben-]Dimension, die von zwei Würfeln begrenzt wird, die drei farbige Flächen haben. In derselben Weise müssen wir nun durch den weißen Würfel den grünblau-roten Würfel durchgehen lassen (Figur 28.2), ebenso dann den blau-weiß-roten Würfel durch das Grün (Figur 28.3). Bei der letzten Figur (Figur 28.4) haben wir einen blau-grün-weißen Würfel, der durch eine rote Dimension durchgehen muß, das heißt, in einer Farbe verschwinden muß, die er nicht selbst hat, um nachher wieder in seinen ureigenen Farben auf der anderen Seite zu erscheinen.

Diese vier Würfel verhalten sich genauso wie vorhin unsere drei Quadrate. Wenn Sie sich nun klarmachen, daß wir sechs Quadrate brauchen, damit ein Würfel begrenzt wird, so haben wir acht Würfel nötig,” um ein analoges vierdimensionales Gebilde, den Tessarakt, zu begrenzen.?” Wie wir dort drei Hilfsquadrate bekommen haben, die nur das Verschwinden durch die andere Dimension bedeuten, so bekommen wir hier im ganzen zwölf Würfel, welche sich zueinander so verhalten, wie diese neun Figuren in der Ebene sich verhalten. Dann haben wir dasselbe mit dem Würfel getan, was wir früher mit den Quadraten taten, und indem wir jedesmal eine neue Farbe wählten, trat eine neue Dimension zu den andern hinzu. So denken wir uns also, wir stellen farbenbildlich einen Körper dar, der vier Dimensionen hat dadurch, daß wir nach vier Richtungen hin vier verschiedene Farben haben, wobei jeder [einzelne] Würfel drei Farben hat und durch die vierte [Farbe] hindurchgeht.

Der Sinn, den dieses Ersetzen der Dimensionen durch die Farben hat, besteht darin, daß wir, solange wir bei den [drei] Dimensionen bleiben, die drei Dimensionen nicht in die [zweidimensionale] Ebene bringen können. Nehmen wir aber dafür drei Farben, so können wir es tun. Ebenso machen wir es mit vier Dimensionen, wenn wir sie durch [vier] Farben im dreidimensionalen Raum zur bildlichen Darstellung bringen wollen. Das ist zunächst eine Art, wie ich Sie auf die doch sonst komplizierten Dinge hinleiten möchte, und wie sie Hinton in seinem Problem [der dreidimensionalen Darstellung vierdimensionaler Gebilde] gebraucht hat.

Ich möchte nun noch einmal den Würfel in der Ebene ausbreiten, ihn nochmals in die Ebene umlegen. Das will ich an die Tafel zeichnen. Sehen Sie zunächst von dem untersten Quadrat [der Figur 25] ab, und denken Sie sich, daß Sie nur zweidimensional sehen könnten, also nur das sehen könnten, was in der Fläche der Tafel ausgebreitet ist. Wenn wir fünf Quadrate so zusammengefügt haben, wie in diesem Falle, daß sie so gelagert sind, daß das eine Quadrat in die Mitte hineinkommt, so bleibt diese innere Fläche unsichtbar (Figur 29). Sie können von allen Seiten herumgehen. Sie können Quadrat 5, da Sie nur in zwei Dimensionen sehen können, nicht erblicken.

Nun wollen wir einmal dieselbe Sache, die wir hier mit fünf von den sechs Seitenquadraten des Würfels angestellt haben, mit sieben von den acht Grenzwürfeln machen, die den Tessarakt bilden, wenn wir unser vierdimensionales Gebilde in den Raum ausbreiten. Ich will die sieben Würfel analog legen, wie ich es mit den Flächen des Würfels auf der Tafel tat; nur haben wir jetzt Würfel, wo wir vorher Quadrate hatten. Nun haben wir hicr die entsprechende Raumfigur, ganz analog geformt. Damit haben wir dasselbe für den dreidimensionalen Raum, was wir vorher für die zweidimensionale Fläche hatten. Wie vorher ein Quadrat, so ist jetzt der siebente Würfel vollständig von allen Seiten verdeckt, den ein Wesen, das [bloß] die Fähigkeit zum dreidimensionalen Schauen hat, niemals wird sehen können (Figur 30). Könnten wir diese Figuren so zusammenklappen wie die sechs abgewickelten Quadrate des Würfels, so könnten wir aus der dritten in die vierte Dimension übergehen. Wir haben gezeigt, wie man sich davon durch Farben-Übergänge eine Vorstellung bilden kann.”

Damit haben wir wenigstens gezeigt, wie man sich, trotzdem die Menschen nur drei Dimensionen wahrnehmen können, doch einen vierdimensionalen Raum vorstellen kann. Nun könnten Sie sich noch fragen, wie man von dem wirklichen vierdimensionalen Raum eine mögliche Vorstellung gewinnen kann. Und da möchte ich Sie hinweisen auf etwas, das man das eigentliche «alchemistische Geheimnis» nennt. Denn die wirkliche Anschauung des vierdimensionalen Raumes hängt in gewisser Weise mit dem zusammen, was die Alchemisten «Verwandlung» nannten.

[Erste Textvariante:] Derjenige, welcher eine wirkliche Anschauung von dem vierdimensionalen Raum sich erwerben will, muß ganz bestimmte Anschauungsübungen machen. Diese bestehen darin, daß er sich zunächst eine ganz klare Anschauung, eine vertiefte Anschauung, nicht Vorstellung, bildet von dem, was man Wasser nennt. Eine solche Anschauung von dem Wasser ist nicht so leicht zu kriegen. Man muß lange meditieren und sich sehr genau in die Natur des Wassers vertiefen, man muß sozusagen hineinkriechen in die Natur des Wassers. Das zweite ist, daß man sich eine Anschauung verschafft von der Natur des Lichtes. Das Licht ist etwas, was der Mensch zwar kennt, aber nur so kennt, wie er es von Außen empfängt. Nun kommt der Mensch dadurch, daß er meditiert, dazu, das innere Gegenbild des äußeren Lichtes zu bekommen, zu wissen, wodurch und woher das Licht entsteht, so daß er dadurch selbst so etwas wie Licht hervorbringen, erzeugen kann. Diese Fähigkeit, Licht hervorbringen, erzeugen zu können, eignet sich der Yogi [Geheimschüler] an durch Meditation. Das kann derjenige, welcher reine Begriffe wirklich meditativ in seiner Seele anwesend zu haben vermag, der reine Begriffe wirklich meditativ auf seine Seele wirken läßt, der sinnlichkeitsfrei denken kann. Dann entspringt dem Begriffe das Licht. Dann geht ihm die ganze Umwelt auf als flutendes Licht. Der Geheimschüler muß nun gleichsam chemisch verbinden die Anschauung, die er sich von Wasser gebildet hat, mit der Anschauung des Lichtes. Das vom Licht ganz durchdrungene Wasser ist ein Körper, der von den Alchemisten genannt wird Merkurius. Wasser plus Licht heißt in der Sprache der Alchemisten Merkurius. Dieses alchemistische Merkur ist aber nicht das gewöhnliche Quecksilber. Sie werden die Sache nicht in dieser Form [überliefert] erhalten haben. Man muß erst in sich die Fähigkeit erwecken, aus dem [Umgehen mit den reinen] Begriffen selbst das Licht zu erzeugen. Merkurius ist diese Vermischung [des Lichtes] mit der Anschauung des Wassers, diese lichtdurchdrungene Wasserkraft, in deren Besitz man sich dann versetzt. Das ist das eine Element der astralischen Welt.

Das zweite [Element] entsteht dadurch, daß man sich, ebenso wie man vom Wasser sich eine Anschauung gebildet hat, man sich von der Luft eine Anschauung bildet, daß wir also die Kraft der Luft durch einen geistigen Vorgang heraussaugen. Wenn Sie [auf der anderen Seite Ihr] Gefühl in sich in gewisser Weise konzentrieren, so erzeugen, so entzünden Sie durch das Gefühl das Feuer. [Wenn Sie die Kraft der Luft gleichsam chemisch verbinden mit dem durch Gefühl erzeugten Feuer, so] bekommen Sie «Feuerluft». Sie wissen, daß in Goethes «Faust» von Feuerluft gesprochen wird.” Das ist etwas, wo das Innere des Menschen mitarbeiten muß. Also das eine Element wird [aus einem gegebenen Element, der Luft,] herausgesogen, das andere [das Feuer oder die Wärme] wird von Ihnen selbst erzeugt. Diese Luft plus Feuer nannten die Alchemisten Schwefel, Sulfur, leuchtende Feuerluft.

Wenn Sie nun diese leuchtende Feuerluft in einem wäßrigen Elemente haben, dann haben Sie in Wahrheit jene [astrale] Materie, von der es in der Bibel heißt: und der Geist Gottes schwebte, oder brütete, über den «Wassern».”

[Das dritte Element entsteht, wenn] man der Erde die Kraft entzieht und das dann verbindet mit den [geistigen Kräften im] «Schall»; dann hat man das, was [hier] Geist Gottes genannt wird. Daher wird es auch «Donner» genannt. [Wirkender] Geist Gottes ist Donner, ist Erde plus Schall. Der Geist Gottes [schwebt also über der] astralen Materie.

Jene «Wasser» sind nicht gewöhnliche Wasser, sondern was man eigentlich astrale Materie nennt. Diese besteht aus vier Arten von Kräften: Wasser, Luft, Licht und Feuer. Die Anordnung dieser vier Kräfte stellt sich der astralischen Anschauung als die vier Dimensionen des astralen Raumes dar. So sind sie in der Wirklichkeit. Es sieht im Astralen eben ganz anders aus als in unserer Welt, Manches, was als astral aufgefaßt wird, ist nur eine Projektion des Astralen in den physischen Raum.

Sie sehen, dasjenige, was astral ist, ist halb subjektiv [das heißt dem Subjekt passiv gegeben], halb Wasser und Luft, denn Licht und Gefühl [Feuer] sind objektiv, [das heißt vom Subjekt tätig zur Erscheinung gebracht]. Nur einen Teil von dem, was astral ist, kann man außen [als dem Subjekt gegeben] finden, aus der Umwelt gewinnen. Den anderen Teil muß man subjektiv [durch eigene Tätigkeit] dazubringen. Aus Begriffs- und Gefühlskräften gewinnt man [aus dem Gegebenen] durch [tätige] Objektivierung das andere. Im Astralen haben wir also Subjektiv-Objektives.

Im Devachan gibt es gar keine [für das Subjekt bloß gegebene] Objektivität mehr. Man würde dort ein völlig subjektives Element haben.

Wir haben eben da etwas, was der Mensch erst [aus sich heraus] erzeugen muß, wenn wir vom astralen Raum sprechen. So ist alles, was wir hier tun, das Symbolische, [nur] eine sinnbildliche Darstellung für die höheren Welten, für die devachanische Welt, die in der Art wirklich sind, wie ich es Ihnen in diesen Andeutungen auseinandergesetzt habe. Es ist das, was in diesen höheren Welten liegt, nur dadurch zu erreichen, daß man in sich selbst neue Anschauungsmöglichkeiten entwickelt. Der Mensch muß selbst etwas dazu tun.

[Zweite Textvariante (Vegelahn):] Derjenige, welcher eine wirkliche Anschauung des vierdimensionalen Raumes sich erwerben will, muß ganz bestimmte Anschauungsübungen machen. Er bildet sich zunächst eine ganz klare, vertiefte Anschauung vom Wasser. Eine solche Anschauung ist nicht so ohne weiteres zu bekommen, man muß sich sehr genau in die Natur des Wassers vertiefen; man muß sozusagen hineinkriechen in das Wasser. Das zweite ist, daß man sich eine Anschauung von der Natur des Lichtes verschafft; das Licht ist etwas, was der Mensch zwar kennt, aber nur so, daß er es von außen empfängt; durch das Meditieren kann er das innere Gegenbild des Lichtes bekommen, wissen, woher Licht entsteht, und daher selbst Licht hervorbringen. Das kann derjenige, der reine Begriffe wirklich meditativ auf seine Seele wirken läßt, der ein sinnlichkeitsfreies Denken hat. Dann geht ihm die ganze Umwelt als flutendes Licht auf, und nun muß er gleichsam chemisch die Vorstellung, die er sich vom Wasser gebildet hat, mit der des Lichtes verbinden. Dieses von Licht ganz durchdrungene Wasser ist ein Körper, der von den Alchemisten «Merkurius» genannt wurde. Das alchemistische Merkur ist aber nicht das gewöhnliche Quecksilber. Erst muß man in sich die Fähigkeit erwecken, aus dem Begriff des Lichtes Merkurius zu erzeugen. Merkurius, lichtdurchdrungene Wasserkraft, ist dasjenige, in dessen Besitz man sich dann versetzt. Das ist das eine Element der astralen Welt.

Das zweite entsteht dadurch, daß Sie sich ebenso eine anschauliche Vorstellung von der Luft machen, dann die Kraft der Luft durch einen geistigen Vorgang heraussaugen, sie mit dem Gefühl in sich verbinden, und Sie entzünden so den Begriff «Wärme», «Feuer», dann bekommen Sie «Feuerluft». Also das eine Element wird herausgesogen, das andere wird von Ihnen selbst erzeugt. Dieses — Luft und Feuer — nannten die Alchemisten «Schwefel», Sulfur, leuchtende Feuerluft. Im wäßrigen Elemente, da haben Sie in Wahrheit jene Materie, von der es heißt: «und der Geist Gottes schwebte über den Wassern».

Das dritte Element ist «Geist-Gott», das ist «Erde» verbunden mit «Schall». Das ist eben was entsteht, wenn man der Erde die Kräfte entzieht und mit dem Schall verbindet. Jene «Wasser» sind nicht gewöhnliche Wasser, sondern was man eigentlich astrale Materie nennt. Diese besteht aus vier Arten von Kräften: Wasser, Luft, Licht und Feuer. Und das stellt sich dar als die vier Dimensionen des astralen Raumes.

Sie sehen, dasjenige, was astral ist, ist halb subjektiv; nur einen Teil dessen, was astral ist, kann man aus der Umwelt gewinnen; aus Begriffs- und Gefühlskräften gewinnt man durch Objektivierung das andere. Im Devachan würde man ein völlig subjektives Element haben; dort gibt es keine Objektivität. So ist alles, was wir hier tun, das Symbolische, eine sinnbildliche Darstellung für die devachanische Welt. Alles, was in den höheren Welten liegt, ist nur dadurch zu erreichen, daß Sie neue Anschauungen in sich selbst entwickeln. Der Mensch muß selbst etwas dazu tun.