Scientific Disciplines and Anthroposophy

GA 73a

1 April 1920, Dornach

Translated by Steiner Online Library

8. Question Following a Lecture by Oskar Schmiedel on “Anthroposophy and the Theory of Colors”

Preliminary remark: A question was asked about the field of electrical forces. The stenographer did not note down the wording of the question.

Rudolf Steiner: This is a question about which one should actually give not just one lecture but a whole series — quite apart from the fact that the question is not related to the topic of this evening.

What was presented yesterday [in Mr. Stockmeyer's lecture] tried to point out how we have to distinguish, so to speak, in the field of the imponderable - in contrast to the field of the ponderable: a field of light, a chemical field and a field of life. Descending from the imponderable to the ponderable, we come to the region of heat, which to some extent is common to both, then to the region of air, then to the region of liquid and solid bodies. Within these regions, nothing can be found, especially for those who are able to consider things phenomenologically, that belongs to the region of electrical forces. The question here was only about electrical forces. And to arrive at an answer to this question, which, I would like to say, is not in any way lay, is only possible if one relates the whole field of phenomena, the whole field of what is empirically given to man in his environment, to man himself. I do not want to say that there cannot also be a way of looking at it that, as it were, disregards the human being and only considers what, in natural phenomena, well, to put it bluntly, is not the concern of human beings. But one comes to an understanding from different points of view, and one of the points of view should be characterized here, at least in terms of its significance.

If you consider everything that belongs to the realm of the ponderable, that is, everything solid, liquid, expandable, expandable, gaseous, you will find, starting from this realm, such effects that also have more or less material parallels in the human organism. But the closer you approach the realm of the imponderable, the more you will find that the parallel phenomena, at least initially given for consciousness, can be attributed to the soul. Those who are not satisfied with all kinds of word definitions or coinages, but who want to get to the bottom of things, will find that even the explanation and experience of warmth rises into the soul.

When we then come to the area of light effects, we have first given the light area as our light field, as something that lies in the area of sensory eye perceptions, and with that these take on a character of the soul. Allow me the expression: we have filtered the scope of eye perceptions into a certain sum of ideas.

If we now proceed to the field of the so-called chemical effects, it might seem doubtful or debatable, according to the usual discussions of today's chemistry, to say that we are also dealing with an ascent to the soul when we speak of the effect of the chemical field on the human being. However, one need only look at what the physiological-psychological study of the visual process has already provided today, and one will find that much of the kind that relates to chemical effects is already mixed into it. It has indeed become necessary, and rightly so, to speak of a kind of chemism if one wants to describe the processes that take place inside the eye during the visual process.

Of course, experiments in this area are thoroughly tainted by current material conceptions; but at this point even contemporary science is to a certain extent, I might say, brought to see, at least in a certain area, the very first, most elementary beginnings of the right way. And when we speak of chemistry in our external life, in so far as it relates to our consciousness of ideas through the process of seeing, we actually speak in a similar way to how we speak when we simply look at the shaped body, that is, the mere surface structure and what we make of the surface structure as an inner image of some solid body. Anyone who, as a proper psychologist, can analyze the relationships between the idea of a shaped, solid body and the exterior that gives rise to this idea will find that this analysis must be fairly parallel to that which relates to what goes on below the surface, so to speak, below the shaped surface of the outer body, as a chemical process, and what is then, through the process of seeing, the inner, soul-like property of the human being.

Something very similar applies to the phenomena of life. Thus, advancing from the ponderable to the imponderable, we come to the conclusion that, in the case of parallel experiences within the human being, we have to assume processes of consciousness that are strongly reminiscent of the imaginative. We can therefore say: if we ascend – if we remember yesterday's scheme [of Mr. Stockmeyer] – from the solid to the liquid, to the gaseous, to the heat-loving, light-loving, to the chemical element – if we ascend here, we come to areas that have their correlate in the human being through the imaginative.

[We ascend] from the ponderable to the imponderable in nature and from the processes that take place in the organism inside the human being - which certainly also underlie consciousness, but which do not enter into consciousness as such - up to the conceptual. Now, however, psychology does not yet have an appropriate method for, I would say, really presenting this whole range of a person's inner experience to human attention in an orderly way.

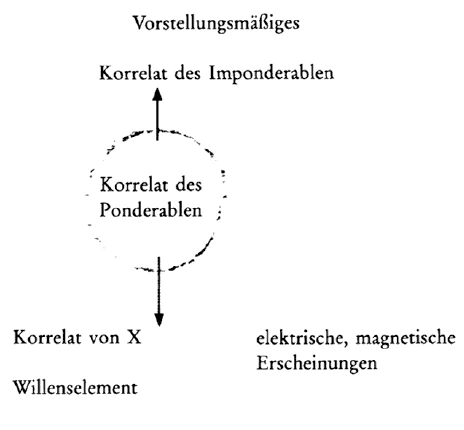

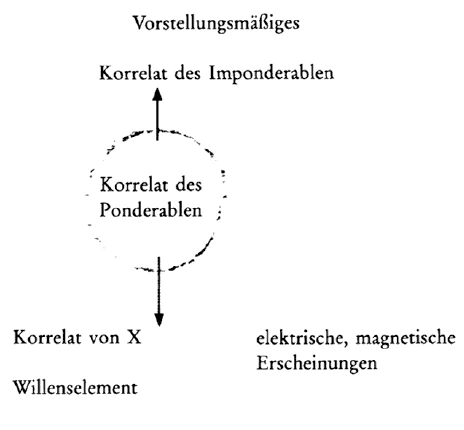

Today, people tend to avoid talking about the actual affects of the soul, about imagination, feeling, will, and so on. Psychology, too, has suffered from the materialistic world view, and it has suffered from this materialistic world view in that it is unable to find any proper ideas about the soul-related. Anyone who wants to find such proper ideas about the soul-related must, of course, completely abandon the ideas of Wundt or the like, which are still regarded as very scientific by so many today. All this talk is basically nothing that even remotely touches the matter. Anyone who studies Wundt's many books will find that it has indeed had a very strong influence, because Wundt came from materialistic physiology into the field of psychology and then even into the field of philosophy. One will find that there is absolutely no possibility of arriving at an appropriate view of the nature of representation and the nature of will. I could mention many other names, not only Wundt's, about whom the same could be said. If one can arrive at such an objective view of the nature of representations, one sees that just as one must raise the correlate of the ponderable to the correlate of the imponderable – see the following diagram – and thereby find the representational in man, so one must go below the correlate of the ponderable in man in order to advance. And there we come to the correlate of something which I would initially like to describe as X. Let us look for it in the human being itself. We find it in the will element of the human being. To deal with what lies between the two and how it lies between the two would be taking things too far today.

We come to the will element of the human being and must then ask: What is the relationship between this will element of the human being and its relationship to external nature? What is this X? What is the correlate of the will, just as the perceptions are the given of the affects in the imponderable? Then one must say to oneself, in spiritual scientific terms: this correlate in nature is the electrical and also the magnetic phenomena – processes, I could say better. And just as in the subjective-objective there is a relationship between the conceptual and the realm of the imponderable, as I called it yesterday, so there is a relationship between the volitional element in man and the electrical, electromagnetic and magnetic realm in non-human nature. If today, when, I would like to say, empiricism is subjugating the reluctant materialistic minds, if today you are again looking for something that can lead you to, well, I would like to say at least make the first step of materialism towards these things, you will find that physics has been forced in recent years to abandon the old concept of matter and to recognize in the electron and ion theory a certain identity between what, if I may express myself trivially, flies through space as free electricity space and what flies through space as electricity bound to so-called matter; in any case, it has been forced to recognize that which flies through space as electricity and represents a certain speed in flying through space. This speed, when expressed in mathematical formulas, now shows exactly the same properties as matter itself. As a result, the concept of matter merged with the concept of electrical effects.

If you consider this, you will say to yourself: There is no reason to speak of an electromagnetic or other light theory, but what is present is that when we look at the outside world, where we do not perceive the electrical directly through the senses, we must somehow suspect it in what is now usually called the material. It lies further from us than what is perceptible through the senses; and this more distant element expresses itself precisely by being related to what lies further from the subjective consciousness of the human being than his world of ideas, namely his world of will. When you descend into the region of the human being that I have designated as the middle region, and then descend further, you will find this descent to be very much the same as descending into the nature of the will. You only need to see how man, although he lives with his soul in the world of his ideas, does not have the actual entity of the will present in his consciousness, but rather deeply buried in the unconscious.

In spiritual scientific terms, this would have to be expressed as follows: In the life of ideas we are actually only awake, in the life of the will we sleep, even when we are awake. We only have perceptions in our life of will. But what this element of the will itself is like, when I just stretch out a hand, eludes ordinary consciousness. It eludes us inwardly as a correlate, just as the electrical eludes us outwardly in the material, in the direct perception that one has of it, for example, in relation to color or to what is visible at all.

And so, if we are looking for a path for the fields of luminosity, chemism and so on, we come from the ponderable into the imponderable by moving upwards. But then, by moving downwards, we come to the realm that lies below the ponderable, as it were. And we will then penetrate into the realm of electrical and magnetic phenomena. Anyone who wants to see with open eyes how, for example, the earth itself has a magnetic effect, how the earth as such is the carrier of electrical effects, will see a fruitful path opened up in this observation, which is of course nothing more than a continuation of phenomenology, in order to really penetrate not only the field of [extra-terrestrial] electrical phenomena, but also, let us say, the electrical phenomena bound to the earth's planets. And an immensely fruitful field is opening up for the study of telluric and extratelluric electrical phenomena, so that one can almost, or not only almost, say in all fields: If we do not close the door to the essential nature of things by stating from the outset what may be thought about these phenomena of the external world and their connection with man - for example, what can be expressed mathematically - but if we have the will to enter into the real phenomena, then the phenomena actually begin to speak their own language.

And it is simply a misunderstood Kantianism, which is also a misunderstanding of the world view, when it is constantly being said that one cannot penetrate from the outside world of phenomena into the essence of things. Whoever can somehow logically approach such thoughts, whoever has logic, has knowledge in his soul, so that he can approach such things, he realizes that this talk of phenomena and of what stands behind it as the “thing in itself” means no more than if I say: here I have written down S and O, I do not see the other, I cannot get from the $S and O to the thing in itself, that tells me nothing, that is a theory-appearance. But if I don't just look at the $ and O, but if I am able to read further and to read the phenomena, but here in this case the letters, not just look at them in such a way that I say: there I have the phenomenon; I cannot get behind this phenomenon, I do not enter into the “thing in itself,” but when I look at the phenomena, as they mutually illuminate each other, just as darkness is illuminated, then the reading of the phenomena becomes speech and expresses that which is alive in the essence of things. It is mere verbiage to speak of the opposition of phenomena and of the essence of things; it is like philosophizing about the letter-logic in Goethe's “Faust” and the meaning of Goethe's “Faust”: if one has successively let all the letters that belong to “Faust” speak, then the essence of “Faust” is revealed. In a real phenomenology, phenomena are not such that they are of the same kind or stand side by side; they relate to one another, mutually elucidate one another, and the like. The one who practices real phenomenology comes to the essence of things precisely by practicing real phenomenology.

It would really be a matter of the Kantian inert mind of philosophy finally breaking free from the inertia of accumulating the “opposites in themselves” and the “thing in itself”, which have now confused minds and spirits long enough to really be able to look at the tremendous progress that has also been made in the epistemological relationship through Goetheanism.

This is precisely what is so important for anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, that attention is drawn to such things and that they can indeed be used to fertilize what in turn leads to an inner relationship between the human being and the spiritual substance in the world - while one has artificially put on, let's say, a suede skin, these forms of all kinds of criticism-of-practical-and-theoretical-reason-blinkers, through which one cannot see through. These are the things that are at stake today.

Anthroposophically oriented spiritual science should certainly not be somehow sectarian; it should certainly not consist merely of explaining to people in some closed circles over tea that the human being consists is composed of a physical body, an etheric body, an astral body and an ego. This, of course, is the kind of stuff that is taught in seance circles over a cup of tea, and it is easy to make fun of those who gain some outer, but also misunderstood, knowledge from such quackery. But spiritual science – one can feel this when one really familiarizes oneself with it – spiritual science is actually capable of stimulating many things anew that really need to be stimulated if we want to make progress. The decadence, the destruction and the social chaos that we are experiencing today have not arisen merely from the sphere of the outer life of our time, but also from the inner human powers of destruction; and these inner human powers of destruction have truly not come from the least of what people have thought through long periods of time.

In this time it is not at all surprising that people arise who find it appropriate to compare Goethe's memories of an old mystic, which he expresses in his saying:

If the eye were not sunlike

How could we behold the light?

If the power of God does not live in us,

How can we be delighted with the divine?

to encounter with the saying: “If the eye were not ink-like, how could we see the writing...”

Indeed, esteemed attendees, I could talk at length about the application of Goethe's saying today, but that would take until tomorrow. So, in conclusion, I would like to summarize what I said about Goetheanism and the present time in something similar to a saying that ties in with what I just mentioned. It is indeed true that the present time, with all that is chaotic in it, could not be as it is if the views of people like Ostwald and similar ones did not haunt it.

If the present world were not so Ostwald-like, how could it see all the external effects of nature so wrongly? If there were not so much of Ostwald's power in present-day people, how could they achieve so much in all kinds of materialistic-physical and similar things, which now truly do not work to a high degree for the true progress of science, but rather against it.

8. Fragenbeantwortung

nach dem Vortrag von Oskar Schmiedel über «Anthroposophie und Farbenlehre»

Vorbemerkung: Es wurde eine Frage gestellt über das Gebiet der elektrischen Kräfte. Der Wortlaut der Frage ist vom Stenographen nicht notiert worden.

Rudolf Steiner: Das ist eine Frage, über die man eigentlich nicht einen, sondern eine ganze Reihe von Vorträgen halten müßte - abgesehen davon, daß ja die Frage gar nicht mit dem Thema des heutigen Abends zusammenhängt.

Dasjenige, was gestern dargestellt worden ist [im Vortrag von Herrn Stockmeyer], das versuchte ja mit darauf hinzuweisen, wie wir zu unterscheiden haben gewissermaßen im Gebiete des Imponderablen - im Gegensatze zu dem Gebiete des Ponderablen -: ein Lichtgebiet, ein chemisches Gebiet und ein Lebensgebiet. Wenn wir von dem Imponderablen zu dem Ponderablen heruntersteigen, kommen wir durch das Wärmegebiet, das gewissermaßen an beiden teilnimmt, dann zum Luftgebiet, dann zu dem Gebiet der flüssigen und zu dem Gebiet der festen Körper. Innerhalb dieser Gebiete ist ja- namentlich für den, der imstande ist, die Dinge phänomenologisch zu betrachten - nichts von dem zu finden, was in das Gebiet der elektrischen Kräfte gehört. Es wurde ja hier nur nach den elektrischen Kräften gefragt. Und in dieser Frage zu einer Beantwortung zu kommen, die, ich möchte sagen, nicht irgendwie laienhaft ist, ist nur möglich, wenn man das ganze Gebiet der Erscheinungen, das ganze Gebiet desjenigen, was dem Menschen in seiner Umgebung empirisch gegeben ist, auf den Menschen selbst bezieht. Ich will nicht sagen, daß es nicht auch eine Betrachtungsweise geben kann, die gewissermaßen vom Menschen absieht und nur das ins Auge faßt, was in den Naturerscheinungen, nun, trocken gesagt, den Menschen nichts angeht. Aber man kommt da zu einem Begreifen von verschiedenen Gesichtspunkten aus, und einer der Gesichtspunkte soll hier wenigstens seiner Bedeutung nach gekennzeichnet werden.

Wenn Sie all das ins Auge fassen, was in das Gebiet des Ponderablen gehört, also alles Feste, Flüssige, Ausdehnungsfähige, Ausdehnbare, Gasförmige, so werden Sie, ausgehend von diesem Gebiete, solche Wirkungen finden, die auch in dem menschlichen Organismus mehr oder weniger materielle Parallelerscheinungen haben. Je weiter Sie aber sich nähern dem Gebiete des Imponderablen, umso mehr kommen Sie zu solchen, für das Bewußtsein wenigstens zunächst gegebenen Parallelerscheinungen, welche dem Seelischen zuzuschreiben sind. Derjenige, der nicht sich begnügt mit allerlei Wortdefinitionen oder Wortprägungen, sondern der auf die Sachen eingehen will, der wird finden, daß schon das Erklären, das Erleben des Wärmemäßigen ins Seelische heraufgeht.

Kommen wir dann in das Gebiet des Lichtmäßigen, so haben wir zunächst einmal das Lichtgebiet gegeben als unser Lichtfeld, als etwas, was im Gebiet der sinnlichen Augenwahrnehmungen liegt, und damit gewinnen diese einen Charakter des Seelischen. Gestatten Sie den Ausdruck: Filtriert haben wir den Umfang der Augenwahrnehmungen in einer gewissen Summe von Vorstellungen gegeben.

Schreiten wir nun weiter zu dem Gebiete der sogenannten chemischen Effekte, so könnte es nach den gewöhnlichen Auseinandersetzungen der heutigen Chemie allerdings zweifelhaft oder bezweifelbar erscheinen zu sagen, daß wir es auch da zu tun haben mit einem Heraufrücken zu dem Seelischen, wenn wir von der Wirkung des chemischen Gebietes auf den Menschen sprechen. Allein, man braucht ja nur ein wenig einzugehen auf das, was heute doch schon die physiologisch-psychologische Betrachtung des Sehvorganges liefert, und man wird finden, daß in diesen [Sehvorgang] schon vieles von der Art hineingemischt ist, das sich auf chemische Effekte bezieht. Es ist in der Tat notwendig geworden, und zwar mit Recht, von einer Art von Chemismus zu sprechen, wenn man jene Vorgänge schildern will, die sich abspielen beim Sehvorgang im Innern des Auges.

Die Versuche auf diesem Gebiete sind ja natürlich durchaus angekränkelt von den gegenwärtigen materiellen Vorstellungen; aber es ist an diesem Punkte sogar die zeitgenössische Wissenschaft schon bis zu einem gewissen Grade, ich möchte sagen herangebändigt, in einem bestimmten Gebiete wenigstens die allerersten, elementarsten Anfänge eines Richtigen zu sehen. Und wenn wir vom Chemismus im äußeren Leben sprechen, insofern er sich durch den Sehvorgang auf unser Bewußtseinsgebiet der Vorstellungen bezieht, so sprechen wir eigentlich ähnlich, wie wir sprechen, sagen wir, wenn wir einfach ins Auge fassen den gestalteten Körper, also die bloße Oberflächengestaltung und dasjenige, was wir uns nach der Oberflächengestaltung als inneres Bild von irgendeinem festen Körper machen. Wer analysieren kann als ordentlicher Psychologe die Beziehungen zwischen der Vorstellung eines gestalteten, festen Körpers und dem Äußeren, das Veranlassung gibt zu dieser Vorstellung, der wird finden, daß diese Analyse ziemlich parallel sein muß derjenigen, die sich bezieht auf das, was gewissermaßen unter der Oberfläche, unter der gestalteten Oberfläche des äußeren Körpers vor sich geht als Chemismus, was also durch die Oberfläche abgewendet ist, und dem, was dann durch den Sehvorgang innerliches, seelisches Eigentum des Menschen wird.

Etwas ganz Ähnliches liegt vor für die Lebenserscheinungen. Wir kommen also, indem wir von dem Ponderablen zu dem Imponderablen vorrücken, dazu, bei den Parallelerlebnissen im Innern des menschlichen Wesens Bewußtseinsvorgänge annehmen zu müssen, die aber stark den Charakter des Vorstellungsmäßigen tragen. Wir können also sagen: Indem wir - wenn wir uns an das gestrige Schema [von Herrn Stockmeyer] erinnern - aufsteigen vom Festen zum Flüssigen, zum Gasförmigen, zum Wärmehaften, Lichthaften, zum chemischen Elemente -, wenn wir hier aufsteigen, so kommen wir bis zu Gebieten, die ihr Korrelat im menschlichen Wesen durch das Vorstellungsmäßige haben.

[Wir steigen auf] draußen in der Natur vom Ponderablen ins Imponderable und im Innern des Menschen von den Vorgängen, die sich im Organismus abspielen - die ja gewiß auch dem Bewußtsein zugrundeliegen, die aber als solche nicht eingehen ins Bewußtsein - bis herauf zu dem Vorstellungsmäßigen. Nun besteht heute allerdings noch nicht eine sachgemäße Methode in der Psychologie, um, ich möchte sagen diese ganze Skala des inneren Erlebens des Menschen wirklich vor die menschliche Aufmerksamkeit ordentlich hinzustellen.

Man redet im ganzen heute ziemlich herum, wenn man von den eigentlichen Seelenaffekten spricht, von Vorstellen, von Gefühl, Wille und so weiter. Auch die Psychologie hat ja gelitten unter der materialistischen Weltanschauung, und sie hat insofern gelitten unter dieser materialistischen Weltanschauung, als sie nicht imstande ist, überhaupt ordentliche Vorstellungen über das Seelengemäße zu finden. Wer solche ordentliche Vorstellungen über das Seelengemäße finden will, der muß natürlich vollständig abgehen von den heute noch von so vielen als sehr wissenschaftlich angesehenen Redereien etwa Wundts oder dergleichen. Alle diese Redereien sind im Grunde genommen gar nichts, was an die Sache auch nur im entferntesten heranrührt. Wer die vielen Bücher Wundts studiert, der wird finden, daß sich da allerdings sehr stark geltend gemacht hat, daß Wundt von der materialistischen Physiologie hergekommen ist in das Gebiet der Psychologie und dann gar in das Gebiet der Philosophie hinein. Man wird finden, daß da überhaupt gar nicht die Möglichkeit besteht, zu einer sachgemäßen Anschauung über das Wesen der Vorstellung und über das Wesen des Willens zu kommen. Ich könnte noch viele andere Namen sagen, nicht nur den Wundts, über die dasselbe zu sagen wäre. Wenn man nämlich zu einer solchen sachgemäßen Anschauung über das Wesen der Vorstellungen kommen kann, so sieht man: Geradeso wie man das Korrelat des Ponderablen hinaufheben muß zu dem Korrelat des Imponderablen - siehe das folgende Schema - und dadurch das Vorstellungsmäßige im Menschen findet, so muß man sich unter das Korrelat des Ponderablen begeben im Menschen, um weiterzukommen. Und da kommt man zu dem Korrelat von etwas, das ich zunächst als X bezeichnen möchte. Suchen wir es im Menschen selber auf. Wir finden es im Willenselement des Menschen. Auseinanderzusetzen was zwischen beiden liegt und wie es zwischen beiden liegt, würde heute zu weit führen.

Wir kommen zu dem Willenselement des Menschen und müssen dann fragen: Wie verhält es sich denn nun mit diesem Willenselement des Menschen und seinem Verhältnis zur äußeren Natur? Was ist denn dieses X? Von was ist denn der Wille ebenso das Korrelat wie die Vorstellungen das von den Affekten Gegebene im Imponderablen? Da muß man sich dann sagen, geisteswissenschaftlich: dieses Korrelat in der Natur, das sind die elektrischen, auch die magnetischen Erscheinungen - Vorgänge könnte ich besser sagen. Und ebenso wie im Subjektiv-Objektiven eine Beziehung besteht zwischen dem Vorstellungsmäßigen und dem gestern als dem Gebiete des Imponderablen bezeichneten, so besteht eine solche Beziehung zwischen dem Willenselement im Menschen und dem elektrischen, elektro-magnetischen und magnetischen Gebiet in der außermenschlichen Natur. Wenn Sie heute, wo ja, ich möchte sagen herangebändigt werden durch die Empirie die widerstrebenden materialistischen Gemüter, wenn Sie heute ja auch wiederum etwas aufsuchen, welches Sie führen kann dazu, nun, ich möchte sagen wenigstens den ersten Bekenntnisschritt des Materialismus zu diesen Dingen zu machen, so werden Sie finden, daß ja die Physik gezwungen worden ist in den letzten Jahren, abzusehen von dem alten Materiebegriff und in der Elektronen- und IonenTheorie dazu gekommen ist, eine gewisse Identität [anzuerkennen] zwischen dem, was - wenn ich mich trivial ausdrücken darf - als freie Elektrizität durch den Raum fliegt und dem, was als an die sogenannte Materie gebundene Elektrizität durch den Raum fliegt; jedenfalls ist sie zur Anerkennung desjenigen gezwungen worden, was da durch den Raum als Elektrizität fliegt und eine gewisse Geschwindigkeit darstellt in dem Durchfliegen des Raumes. Diese Geschwindigkeit zeigt nun in mathematischer Formel ausdrückbar ganz dieselben Eigenschaften wie die Materie selbst. Dadurch schmolz der Materiebegriff zusammen mit dem Begriff der elektrischen Effekte.

Wenn Sie das ins Auge fassen, dann werden Sie sich sagen: Ein Grund, von einer elektro-magnetischen oder sonstigen Lichttheorie zu sprechen, ist zwar nicht vorhanden, aber was wohl vorhanden ist, das ist, daß wir - wenn wir auf die Außenwelt blicken, wo wir ja das Elektrische nicht direkt durch die Sinne wahrnehmen -es in dem, was nun gewöhnlich das Materielle genannt wird, irgendwie vermuten müssen. Es liegt uns ferner als das, was durch die Sinne wahrnehmbar ist; und dieses Fernerliegende, das drückt sich eben dadurch aus, daß es verwandt ist mit dem, was ja zunächst dem subjektiven Bewußtsein des Menschen ferner liegt als seine Vorstellungwelt, nämlich seine Willenswelt. Wenn Sie bei dem Menschen in das Gebiet hinuntersteigen, das ich als das mittlere bezeichnet habe, und dann weiter hinuntersteigen, so finden Sie dieses Hinuntersteigen sehr identisch mit dem Hinuntersteigen in die Willensnatur. Sie brauchen nur darauf zu sehen, wie der Mensch zwar mit seiner Seele in der Welt seiner Vorstellungen lebt, wie aber das, was die eigentliche Entität des Willens ist, nicht präsent ist in seinem Bewußtsein, wie es tief unten im Unbewußten liegt.

Geisteswissenschaftlich gesagt würde das so ausgesprochen werden müssen: Im Vorstellungsleben wachen wir eigentlich nur, im Willensleben schlafen wir, auch wenn wir wachend sind. Wir haben nur Vorstellungen in unserem Willensleben. Wie aber dieses Element des Willens selber beschaffen ist, wenn ich nur eine Hand ausstrecke, das entzieht sich dem gewöhnlichen Bewußtsein. Es entzieht sich das innerlich als Korrelat, wie sich äußerlich in dem Materiellen das Elektrische der unmittelbaren Anschauung, die man etwa gegenüber dem Farbigen oder dem Sichtbaren überhaupt hat, entzieht.

Und so kommen wir, wenn wir einen Weg suchen für die Felder des Leuchtenden, des Chemismus und so weiter, nach aufwärts steigend aus dem Ponderablen ins Imponderable. Aber dann beim Abwärtssteigen kommen wir gewissermaßen zu dem Gebiete, das unterhalb des Ponderablen liegt. Und man wird dann in das Gebiet der elektrischen, der magnetischen Erscheinungen eindringen. Wer da mit offenen Augen sehen will, wie zum Beispiel die Erde selber magnetartig wirkt, wie die Erde als solche der Träger von elektrischen Effekten ist, der wird gerade in dieser Anschauung, die ja auch nichts anderes ist als eine Fortsetzung der Phänomenologie, einen fruchtbaren Weg eröffnet sehen, um nun wirklich einzudringen nicht nur in das Gebiet der [außerirdischen] elektrischen Erscheinungen, sondern auch der, sagen wir an den Erdplaneten gebundenen elektrischen Erscheinungen. Und es öffnet sich da ein ungeheuer fruchtbares Feld für das Studium des Tellurischen und auch der außertellurischen elektrischen Erscheinungen, so daß man fast, ja nicht nur fast, sondern auf allen Gebieten sagen kann: Verschließt man sich nicht die Türe zu dem Wesenhaften der Dinge dadurch, daß man von vornherein irgend etwas statuiert, was über diese Erscheinungen der Außenwelt und ihren Zusammenhang mit dem Menschen gedacht werden dürfe - zum Beipiel dasjenige, was mathematisch ausdrückbar ist -, sondern hat man den Willen, einzugehen auf die wirklichen Phänomene, dann beginnen die Phänomene eigentlich ihre eigene Sprache zu sprechen.

Und es ist einfach ein mißverstandener Kantianismus, der ja auch ein Mißverständnis der Weltanschauung ist, wenn immerfort davon geredet wird, daß man nicht eindringen kann von der Außenwelt der Erscheinungen in das Wesen der Dinge. Wer irgendwie solchen Gedanken logisch beikommen kann, wer Logik hat, Wissen hat in seiner Seele, daß er solchen Dingen beikommen kann, der sieht ein, daß diese Rederei von Phänomenen und von dem was als «Ding an sich» dahintersteht, nichts weiter bedeutet, als wenn ich sage: hier habe ich S und O aufgeschrieben, das andere sehe ich nicht, ich kann nicht von dem $S und O auf das Ding an sich kommen, das sagt mir nichts, das ist eine Theorie-Erscheinung. Wenn ich aber nicht bloß das $ und O ansehe, sondern wenn ich weiter zu lesen vermag und die Phänomene, hier aber in diesem Falle die Buchstaben weiter zu lesen vermag, nicht bloß so betrachte, daß ich sage: da habe ich das Phänomen; hinter dieses Phänomen kann ich nicht kommen, ich dringe nicht ein in das «Ding an sich», sondern wenn ich die Phänomene betrachte, wie sie sich gegenseitig aufhellen, so wie sich die Dunkelheit aufhellt, dann wird das Lesen der Phänomene zum Sprechen und drückt dasjenige aus, was in dem Wesen der Dinge Lebendiges ist. Es ist nur eine Rederei, von dem Gegensatz der Erscheinungen und des Wesens der Dinge zu sprechen; das ist so, wie wenn man herumphilosophieren würde über die Buchstabenlogik in Goethes «Faust» und den Sinn des Goetheschen «Faust»: wenn man alle die Buchstaben nach und nach hat sprechen lassen, die zum «Faust» gehören, so sei eben das Wesen des «Faust» enthüllt. Bei einer wirklichen Phänomenologie sind die Phänomene ja auch nicht so, daß sie gleichartig sind oder nebeneinanderstehen, sie beziehen sich aufeinander, sie hellen sich gegenseitig auf und dergleichen. Derjenige, der wirkliche Phänomenologie treibt, der kommt eben durch das wirkliche Phänomenologietreiben auf die Wesenheit der Dinge.

Es würde sich wirklich darum handeln, daß der kantisch träge gemachte Verstand der Philosophie nun endlich einmal loskäme von der Trägheit des Häufens von den «Gegensätzen an sich» und dem «Ding an sich», die nun lange genug die Geister und die Gemüter verwirrt haben, um nun wirklich hinschauen zu können auf den ungeheuren Fortschritt, der auch in der erkenntnistheoretischen Beziehung hat gemacht werden können durch den Goetheanismus.

Das ist es gerade, was für anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft so wichtig ist, daß auf solche Dinge hingewiesen und damit in der Tat dasjenige befruchtet werden kann, was nun wiederum zu einer inneren Beziehung des Menschen zu dem Wesenhaften in der Welt führt - während man künstlich sich ein Scheuleder, sagen wir, angelegt hat, diese Formen von allerlei Kritik-der-praktischen-und-theoretischen-Vernunft-Scheuklappen, durch die man nicht hindurchsehen kann. Das sind die Dinge, um die es heute geht.

Anthroposophisch orientierte Geisteswissenschaft soll wahrhaftig nicht irgendwie sektiererisch sein, sie soll wahrhaftig nicht bloß darin bestehen, daß in irgendwelchen abgeschlossenen Zirkeln, bei denen man Tee trinkt, den Leuten erklärt wird, der Mensch bestehe aus physischem Leib, Ätherleib, Astralleib und Ich - wobei man dann freilich über diejenigen, die von solchem tantenhaften Getriebe irgendwelche äußere, aber auch wiederum mißverstandene Erkenntnis gewinnen, sich weidlich lustig machen kann. Sondern Geisteswissenschaft - man kann das wohl fühlen, wenn man sich wirklich bekannt macht damit -, Geisteswissenschaft ist tatsächlich geeignet, manches neu zu befruchten, das wirklich befruchtet werden muß, wenn wir weiterkommen wollen. Was wir heute erleben an Dekadenzerscheinungen, an Zerstörungserscheinungen, an Hereinbrechen von sozialem Chaos, das ist durchaus nicht bloß aus dem Gebiet des äußeren Lebens unserer Zeit heraus entstanden, sondern auch aus dem, was innere menschliche Zerstörungskräfte sind; und diese inneren menschlichen Zerstörungskräfte sind wahrhaftig nicht zum geringsten aus demjenigen gekommen, was die Menschen durch lange Zeiten hindurch gedacht haben.

In dieser Zeit ist es natürlich auch gar nicht verwunderlich, daß Menschen auftreten, die es angemessen finden, den Erinnerungen Goethes an einen alten Mystiker, die er in seinem Spruch ausdrückt:

Wär’ nicht das Auge sonnenhaft

Wie könnten wir das Licht erblicken?

Lebt nicht in uns des Gottes eigne Kraft,

Wie könnt uns Göttliches entzücken?

zu begegnen mit dem Ausspruch: «Wär’ nicht das Auge tintenhaft, wie könnten wir die Schrift erblicken ...».

Allerdings, meine sehr verehrten Anwesenden, über die Anwendung des Goetheschen Spruches könnte ich heute noch lange reden, das heißt, das würde dann bis morgen dauern. Aber so möchte ich zum Schluß wenigstens noch das, was ich über Goetheanismus und die heutige Zeit gesagt habe, in so etwas Ähnlichem wie einem Spruch zusammenfassen, der anknüpft an das, was ich soeben erwähnt habe. Es ist in der Tat wahr, die heutige Zeit mit alle dem, was chaotisch ist in ihr, sie könnte nicht so sein, wenn nicht in ihr drinnen spukten die Anschauungen von Leuten wie Ostwald und ähnlichen:

Wär nicht die gegenwärtige Welt so ostwaldhaft, wie könnte sie alle äußeren Naturwirkungen so verkehrt erblicken? Läg nicht in den Menschen der Gegenwart so viel von Ostwaldkraft, wie könnten sie so ungeheuer viel von allerlei Materialistisch-Physikalischem und dergleichen erreichen, das nun wahrhaftig heute dem wahren Fortschritt der Wissenschaft in hohem Grade nicht zu-, sondern entgegenarbeitet.