Foundation Course

Spiritual Discernment, Religious Feeling, Sacramental Action

GA 343

27 September 1921 a.m., Dornach

II. Essence and Elements of Sacramentalism

[ 1 ] My dear friends! Yesterday my stating point was to indicate in a few words how Anthroposophy can certainly not be considered as an education of religion and in no way can it directly enter into the development of religious life, but only, as I indicated, indirectly. Anthroposophy must, according to its nature, live as a free deed in the human spirit, it must depend on the free deeds of the human spirit—like natural science as well, which heads in the opposite direction—while religious life must be based on communication with the Godhead with whom one knows one is connected and with whom one knows one is dependant in religious life.

[ 2 ] At first a serious abyss could open up between those who can offer Anthroposophy to contemporary civilization, and the blossoming of religious life. Perhaps in the totality of what we will talk about here will show you that this abyss doesn't exist. I would just like to call your attention today to how anthroposophical life intervenes in the academic world in such a way that it lends a religious colouring to it.

[ 3 ] It is quite without doubt that the modern world rules the relationship of humanity to the cosmos and its earthly environment with agnosticism, and religious people who do not acknowledge this, will come up against a very serious mistake. They would like to remain, to a certain extent, stuck in the comfortable old form and would not contribute anything to ensure that the essence of the old form can remain intact for the earth's development. This mistake unfortunately applies to many people at present. They shut themselves off from the necessity that the epoch we are entering into, requires that we clarify and move towards a conscious, awakened knowledge with human prudence in every area. If religious life is artificially distanced from this knowledge, so it would—while undoubtedly knowledge of a larger authority is being addressed—cause this knowledge to perish, as it once before had threatened to do in the 19th century, when the materialistic knowledge wanted to destroy religious life in a certain sense.

[ 4 ] What I have said regarding this must simply penetrate our sensitivities, it must be clear, and when it is clear, my dear friends, then our mental picture, as I bring it up in front of you, will not seem like such a paradox, as it might be for those who encounter and hear it for the first time.

[ 5 ] The agnosticism, the Ignorabimus, is something which has sprung up out of the scientific way of thinking of modern time. What kind of knowledge is it which professes ignorance or agnosticism? It is based on something which it agrees with completely; it is based on the fact that people have gradually been trying to totally shut out their life of soul from knowledge. It is namely so that the ideal human knowledge according to the modern scientist, also the historian, is to shut out subjectivity and only retain what is objectively valid. As a result, the process of obtaining knowledge—for scientific research as well—is completely bound to the physical body of man. Please understand this, my dear friends, in all earnest. Materialism namely has the right when it takes this knowledge which is available to it, not only in regard to what is totally due to material conditions, but which appear as material processes. What really happens between people, in their search for scientific knowledge and the outer world, moves between the outer material things and the relationship to the sense organs; this means their relationship with the material, physical body. The real process of seeking knowledge in connection to the earthly world is a material process right into the final phases of cognition. What the human being experiences in this cognition, is lived through as an observer; he experiences it with his soul-spiritual "side-stepping," so that the human being actually is quite right in the cognitive process as being understood physically and to recognise this as the only decisive conception. The human being as observer, which has no activity within himself—this has already often been mentioned by scientists who have thought about this, recognised it and spoken about it.

[ 6 ] You see, for in this process of acquiring knowledge, where the human being is actually a mere observer, everything a person has as inner journeys in his soul life, is discounted by the observed reality. The human being observes the outer things, he thinks about these outer objects, he is reminded by outer things, but he certainly also observes how in his reminiscences, his memories, how his emotions of feelings and willing come into it, only how this happens, he doesn't know because he is completely unsure about the origin of these feelings and willing, so that for this knowledge, which can only be acknowledged in the present, the only thing which comes into consideration is what happens between the observation and the memory. This is only a picture; it runs as a parallel occurrence next to the real materialistic process running alongside it. The material process is the reality and the recognition runs alongside the material process.

[ 7 ] If one had the means for really absorbing what was approaching in the epoch leading up to the Mystery of Golgotha, in the teachers and pupils of the mysteries, and what in that time, one could say, through three decades during which it happened, the then Gnostic orientated mystery teachers spoke about their most inner heartfelt convictions, then one can do no other than to say: they anticipated that the human being will experience himself as a mere observer in the world, and that even his process of acquiring knowledge will occur without his soul's participation. This experience ruled throughout the prevailing mood of the beings of the mysteries during the times of the Mystery of Golgotha.

[ 8 ] How can we come to terms with this knowledge today regarding ignorance and agnosticism? We arrive, as we've said, at something which appears as a paradox. Knowledge is the result of the material process, even tied to the material world, while the human being experiences spiritually, but is a mere observer in his spirit. If we now expand the Christian point of view of this phenomenon, then we finally reach a point of integrating this knowledge into the process itself that the Christian view of the various human processes ever had. We reach a point in a sense, which we characterised yesterday, to regard the recognition of human sinfulness in our time as the final phase of the Fall of mankind from its former conditions. Only then will we understand our current science out of religious foundations, when we can regard science as the final phase of the expression of the sinful human being, when we can place it into the realm of sin. This is what appears as a paradox. Out of sinfulness comes ignorance, out of sinfulness, religiously expressed, comes agnosticism.

[ 9 ] Only when we feel this way regarding modern science, can we feel Christian towards science. Then again—and we will actually see this in the following days—quite a necessary path results from the understanding of the sinfulness of today's science, an inner human path which can be understood as grace.

[ 10 ] With this I have initially indicated what we will be undertaking in the following days; because sometimes you have to do things a little differently to what is customary with today's science, when one wants to explain things in a proper way. To a certain extent one must first draw the outer circle and go inward from there and not start with a theory and draw conclusions from that.

[ 11 ] With this at least something real is indicated in humanity. If we simply remain stuck in the ordinary knowledge of current science, then we remain stuck in images. The moment we sense within these images—and all of science today is an image—the sinfulness within this modern scientific element, we comprehend matter with a reality within ourselves, then we are on the way to take science itself into reality. One must be able to develop a feeling, if one wants to rise to it, to ask questions in such a way that something of reality is felt: how is it possible, in a religious sense that, what the human being initially experiences as an observer, can be brought into something real through which human life here on earth is not merely a nonhuman, material life and that the human being is not a mere observer but that a person with his own true being can express himself by processing material existence? When does inner life reach into outer reality so that something is created out of the inward experience and a person is no longer only a mere observer?

[ 12 ] You see, there have been attempts to answer this question from time immemorial with the essence of sacramentalism, and one doesn't arrive at another understanding of the essence of sacramentalism than on the basis of such considerations as I've pointed out. First of all, one thing confronts us in human beings and that is the Word.

[ 13 ] The Word is actually for current science something quite mysterious, something secretive; because uttered words are at the same time perceived through the sense of hearing. In man there is a moment which lies in the words, when he utters words and he hears them at the same time. In the eyes, in the ability to see, the process has an active and a passive element completely intertwined; it is also present there but is not yet analysed in physiology today. Actually, it is present in all the senses but in relation to hearing and speaking both the active and passive elements are clearly separated from one another. When we speak, we certainly don't consider ourselves as observers of our lives; when we speak, we participate creatively in our life because speaking is simultaneously connected to our breathing process. What takes place in speaking streams over the breathing process. When we breathe in we bring the pressure of the breathing right into our spinal cord canal and in this way, pressure is translated to the brain and works creatively on the cerebral fluid. In the breathing process the outer world streams into us, moulding ourselves. The air we breathe is firstly outside, it enters into us, works formatively on our cerebral fluid and thus also works formatively in the semi-solid parts of the brain. We only understand the brain correctly if we don't just look at it as something which has grown in humans, but if we look at it as something in progressive interaction with the outer world.

[ 14 ] In this in-streaming of breath we weave the words which we express. I want to firstly only indicate these things, as I suggested, I want to draw an outer circle and then move gradually inward. By our interweaving our words with our breath—which is indicated in the Old Testament as giving humans their origins—blowing in the air to breathe—through which our word unifies with what is considered in the breath of air as divine, we experience the Word as the Creator within us. We observe something in the world process where we are not merely observers but feel our soul's life working creatively into our body.

[ 15 ] We have reached an understanding which allows us to say: in the original creation of mankind was the Word, and everything in human beings was created through the Word.—Just study what it means that the human being, by learning to speak, slowly disentangles his physical organisation through speech. We haven't yet considered the words of the Gospel of St John, but we have discovered the manifestation of something of the bodily nature of the human being in this Gospel. When we contemplate the human being we first of all have his spiritual soul expression and from here the Word comes, which then draws into his bodily organism and shapes him, and thus we have many of these bodily forms which in the course of our lives develop from words themselves, because this is the way we are, we develop out of our words.

[ 16 ] What speech/language means to human beings can only really be studied fully in its depths through spiritual science. Already in the sense of the Testaments we have an interweaving of the words which moves through man as the first divine process, that of breathing. Mere thinking which moves in the sphere of the observer is pushed into the creative sphere. When thinking becomes transformed into words, the Divine empowers these thoughts; it is, one could say, the deification of thoughts occur in the words. When one becomes aware that there is much more to words than speech, then words become something through which a person discovers his first connection, his first communication with the Divine in his own behaviour, a behaviour which is like a condensing; like a thought immersed in feeling. While this is to some extent a route from subjective to objective thought, we have the possibility for something which is spiritually objective, to flow into the word. This can be followed by the idea that much more can exist in words than what is in merely man-made thinking; that to a certain extent something divine can flow into the words and that in the words something divine can be expressed, that a divine message can be contained in the words.

[ 17 ] So we have the first element, that people from out of themselves, find their way going out into the environment, permeated with what is divine in the words. This is somewhat the way the Words of the Gospels were experienced, the in-streaming of the divine in the words of the Gospels which we can feel in the creative activity of the words for ourselves; here we have the first element how man can change from his subjectivity to the objective, like in ritual.

[ 18 ] Now, one can look at what a person doesn't think regarding the world, but what actions he performs in the world. Simply look at human actions. These human actions are seldom regarded in the right light by modern materialism.

Once again, I can only make indications about what this actually involves; we will later enter into them again.

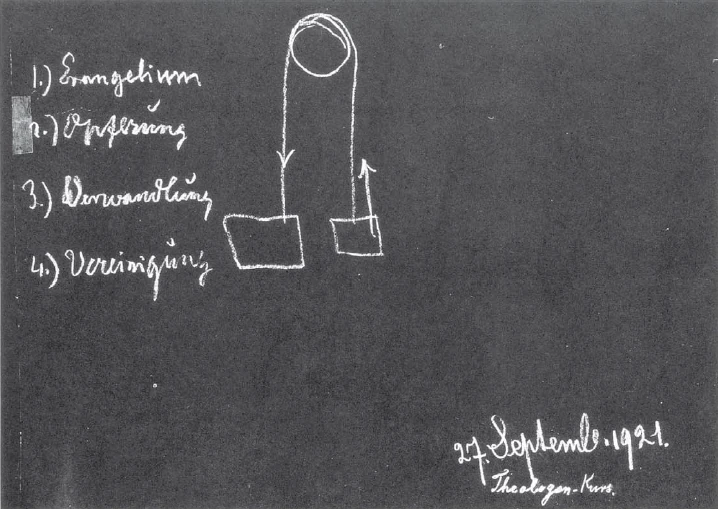

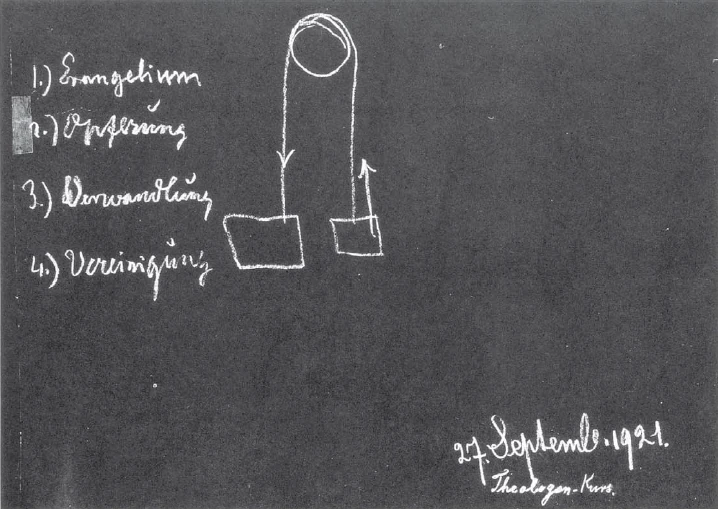

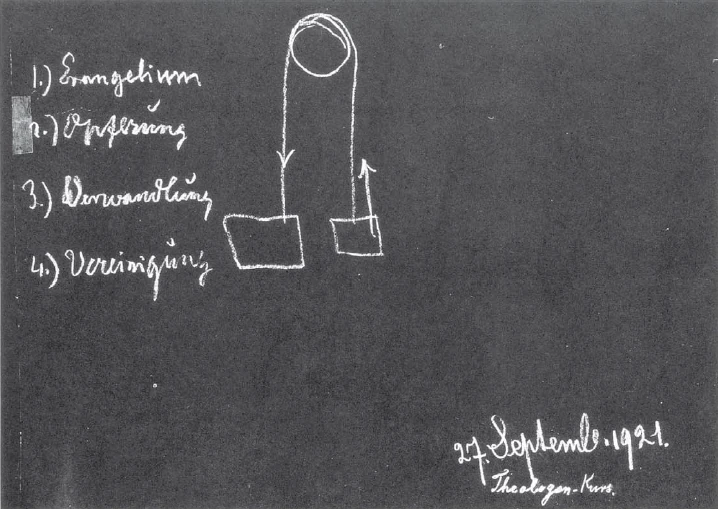

[ 19 ] Just imagine the following contrivance: around a pulley a rope, here a weight, and on the other side a larger weight. The rope is pulled down on the side of the heavier weight and pulled up on the opposite side. The same thing can happen if you now pull on the lighter side and lift the heavier side. You could accomplish something yourself which can also happen as an objective process. In the first place, depending on the heavier weight, it happens without you being there; but when you are there, you can shift the weight. What happens in the outer world can also happen without you.

[ 20 ] This is however a process in inorganic nature. When you study what a person accomplishes in the outer world you realize what is of importance is that it happens in such a way, that it comes from spiritual interrelationships, and that the body of a person only presents the possibility for the action. In our actions we namely—in that we gain knowledge of the world as soul-spiritual observers—only have our body as one ingredient. In our bodies processes take place—processes of movement, of nourishment, of dissolving and so on. What takes place in our bodies is an ingredient, something that is added to what happens objectively. Our body doesn't take part in our actions; we only understand our actions when we consider them when separated from the body. Just as we in the cognitive process, seen materialistically, have something which turns us into observers, so we have in the process of actions for the world, in the process of action, which takes place in the world, something in which the body doesn't participate. Processes which take place in the body remain without cosmic meaning, just like materialistic knowledge has no cosmic meaning. A person remains in materialism in his actions when they only pertain to the earthly, like a hermit standing in the world has no relationship to anything outside of himself. If he searches for this relationship, then he must mix something spiritual into his actions, accomplish actions in such a way that they aren't separated from him, like all earthly actions, then he must allow his thoughts and feelings to enter in a vital way into his actions, so that the actions become signs for what lives in them. Then the actions are a sacrificial act, then they are the sacrifice.

[ 21 ] When we look at knowledge in this way, we see knowledge objectified by the validation of the message in words; if we look at the actions, we have the objectification of action, the drawing out of man alone in what is given in the sacrificial act. Here we first have the relationship of a person to the outer world in the sense that it originates out of the human spirit-soul. Out of the spiritual soul now also rises the imagination—in relation to words, which are no longer experienced as a human, but as a divine revelation—and in relation to the sacrificial act, which is no longer being experienced as the manipulation of the human world, in which man is not involved, but as such is involved with his thoughts, his feelings; this he experiences again in his inner life.

[ 22 ] The other relationship of the human being to the outer world, we find in human nutrition. We actually have three relationships to the outer world: observation through the senses, breathing and nutrition. Everything else can be referred back to these. Breathing is actually positioned between perception and nutrition because one could say that breathing is half perception and half nutrition. It is undeniable that the breathing process stands between the process of perception and nutrition. You see, it is simultaneously connected to the processes of perception and nourishment. Breathing is the synthesis between observation and nutrition.

[ 23 ] Physiology considers nutrition incorrectly. Physiology is of the opinion that we take in nourishment, that we take out of the food what we need and repel the rest. This is not so. That we absorb substance is only a side-effect. The process of life means we are actually constantly opposed and fight back against what is caused by the ingestion of foodstuff into ourselves. We eat, we drink—and the result is something which lies truly very deep in our consciousness, beneath our conscious soul life. What happens there is a constant defensive action. In this physical-physiological process of defence are found the actual processes of life and of nutrition. The life process of nourishment is an averting process. Only when we realize how the organism is organised in this way, to receive the suggestion for a defence—for us to have a defence there naturally has to be suggestion—only when we understand that by the defence against a substance coming from outside as a suggestion in the process of nourishment, will we be able to really understand nourishment. With nourishment a process of aversion is involved, while the absorption of substances is only a side effect through which the finest filaments of the human being the suggestion for resistance is directed from the outside, in order for the aversion to take place in the most outer periphery of the organism. Only at this point of averting does the actual life process of nutrition take place, so that the ordinary earthly process of nourishment is actually a resistance to the earthly. The earthly pushes the nourishing items into us, and we must absorb it, but this is a process of resistance.

[ 24 ] This is the reality, but it is not the way science looks at the whole thing. What is actually happening with this repulsion? Something happens which lies completely outside of human consciousness. When we take up nourishment, it is actually a process of the material world. Each substance is actually a concentrated, reduced world process. Processes of the outer world we take into ourselves, we repel them, but by repelling them, a counter process comes about: the process of the outer world becomes something quite different, transformed, and in this transformation, something happens in us. Outer matter is transformed in us. What becomes of it? It becomes spirit within us. This is something which is ordinarily not seen, that the human being in his actual process of digestion, in his transformation of the outer world steers outer material processes to spiritualization.

In the outer world nature goes through world processes, and as a fragment of this world process, we could call it the origin of a seed, from which all other things originated through the seed serving as nourishment. What happens in the outer world becomes firstly transformed within the human being before it goes further on its way to spirituality. It can't be transformed into the spiritual in the outer world, only within the human being can it change into the spiritual. This is simply an objective fact, which I state here, nothing else. However, what I'm presenting here for you happens outside the world of human thoughts. It happens in the deeper regions of human will and partially in the feeling realms. Only certain parts of the feeling life, and will, take part in the process of nourishment, which I've recently indicated. Thought processes don't take part in it; it goes in the opposite direction; through the Word it goes from below into the formation. Here beneath, we have, coming from outside in the opposite direction, like the way the thought process does it, the process of transformation.

[ 25 ] If one wants to place this transformative process within the human being so that when one looks at a person according to the manner in which he looks at the outer world, then one must place something in the outside world which actually doesn't happen in the outside world, but only within the human being. With this one had placed a sacramental act in the outside world, something which doesn't take place in natural phenomena, but which takes place within the human being as a human mystery. If one wants to take what belongs to the most inner part of man, which we have just characterised, and place this in front of the human being, then one arrives at the conversion of the bread and the wine as the body and blood (of Christ), which is the transubstantiation. The transubstantiation is not an experience of the outside world; the transubstantiation is revealing to the outside world what is fulfilled within the most inner part of the human being. We see in the transubstantiation what we are unable to see in the outside world, because the outside world is a fragment of existence, not a totality; in the sacraments we add that to the outside world in addition to what the kingdom of nature accomplishes within the human being.

[ 26 ] This, my dear friends, is the original idea of the sacrament, that something is added to outer world phenomena, something which inner man doesn't experience consciously but which is within the human being, and because it is not recognised but exists subconsciously, it can through signs be placed into the outside world. To consummate transubstantiation, a person must feel something unconsciously connected with the innermost being of his self to the symbols. He is indeed paving the way for intercommunications with the spirits of the outside world by presenting the transformation, which would otherwise take place behind the veil of memory within him, as a sacrament.

[ 27 ] With this we have not yet grasped what the highest achievable thing is by human beings, we have only grasped the spiritualisation process of substance in the human being, the transformation, the transubstantiation. What happens in man as an objective process takes place, I would say, only as separated from our consciousness by a thin veil, behind our consciousness. This happens because from this side, at every moment of our lives, our "I" is stirred up. We dive down below this transformed substance and by our absorbing the matter of the outside world, our process of life exists in this transformation, by our spiritual soul diving under into the transformation of the outside world, our "I" is continually nourished, our "I" is continuously encouraging the union with the substance transformed by this process. The union with the substance after its transformation represents the accessibility of the ego-manifestation to spiritualisation. Let's consider this in a sacramental way.

If we place the sacramental before us then the participation in the sacrament is such that it is materially represented through symbolism; as soon as it is transubstantiated it becomes united with the human being and here we have the fourth link of what in the ritual can be represented as the sacramental signs in the relationship of the human being to the world.

[ 28 ] If we look at the human beings in as far as they are involved with the outside world, then we have, what I would call, the realization of the process of knowledge (in spirit) in Words, and in the sacrificial act, which appear outwardly in signs, we have indicated everything which a person can unite with in his soul-spirit and actions. If we look at human beings absorbing the outside world, where we have the proclamation of the message in word and the sacrificial act, if we look at human beings who continuously give birth out of the spiritual, then we have realized this in the sacramental acts of transubstantiation and communion.

[ 29 ] With this we have thus the possibility to connect the human being in his relationship to all his actions in the outside world in a real sense. Actions distance themselves from him, his own body walks beside him. In transubstantiation that which does not take place in the world is presented as an event, because the outside world is only a fragment of possible events. In communion a person unites himself with the outside world to which he can't connect through his thinking. Objective processes precede transubstantiation and communion. As a result of this we place a person through a physical-soul-spiritual way in a relationship with the world. We have stopped regarding the human being as in a hermit's existence removed from the world; we've started seeing him as a member of the whole world. We have learnt to regard the world as material, but there, where we see it as a fragment, to look at it as if the spiritual foundation on which matter is based is only a part, spiritualising and perfecting; and we have taken the divine cycle, which is in the outer and inner part of man, and placed it before us ... (Some gaps in stenographer's text made the publisher shorten the text here.)

[ 30 ] This is what the people wanted to present to those who said: The human physical-soul-spiritual relationship to the universe can be brought back through the sacraments; recognised through the proclamation, through the sacrificial act, performed through the transubstantiation and communion. You could live together with the entire world by taking what is usually spread over two halves in a person, the soul-spiritual, which just watches, and the physical, which is just an addition to external actions. These can be united by taking what the mere observer wants to remain in relation to the outside world, sacramentalize it in the proclamation of the Word, in the Gospel—which comes out of the "Angelum," out of the realm permeated by the spiritual world—and in the sacrificial act, experienced in his inner life and through which the human being only becomes complete, sacramentalised in the transubstantiation, the transformation, and then by incorporating the human being into this whole in communion, in union. Here you have a real process which is no mere process of knowledge but a process which is connected to your feeling and will, while the process of knowledge takes place in a cold, frozen region of mere abstraction.

[ 31 ] What takes place in the coldness of knowledge is warmed somewhat by the proclamation of the Word and in the sacrificial act. That which, however, through overheating can no longer exist consciously, because heat numbs consciousness and thus can't be perceptive, which can happen when the phenomenon is elevated to a noumenon/psyche, means that in place of external processes which are perceived by the senses, the external process of sacramental action is imitated by the human being itself, in which sacramental action is regarded as what lies behind nature, which can't be produced by anything else, with an objective meaning in the world, because it places the events of human life itself in the cosmos.

[ 32 ] With this we have given something which our current abstract process for acquiring knowledge actually presents in life. However, a question remains, which is an important question. We can understand that something happens in people through the Word, because the Word works into the corporeality and man forms himself through words. We can also understand that through the sacrificial act something happens in the inner part of man because the sacrificial act is executed in such a way that he is not just holding back what is in his body, but that his feeling and willing takes part in the sacrificial act. As a result, an earthly event in the body is connected to a super-earthly event. This can be comprehended. In fact, quite different feelings are experienced during the sacrificial act than any during any other processes in ordinary outer activities. A dampening of the consciousness which is carried within, is numbed. If we can now say something happens within human beings, then the great question arises which we want to address in future: does this event, which is primarily an independent event, does it not take its course in outer events? Is it not also a world event? If so, then we should ask ourselves, what a person experiences as in an outer action, which is symbolic and thus somehow withdraws from the course of events in natural phenomena—do such actions in their turn somehow weave into the course of events in natural phenomena? Are they something real, outside of the human being? This is the other component of the question. As we said, we will occupy ourselves with this question in the next days.

[ 33 ] You will have already noticed in what has come in front of you, that there are four main elements of the sacrifice of mass which rest on the primordial experiences of consciousness, in the mysteries. The four principal constituents of the sacrifice of mass are namely: reading the Gospel, the Offering, the transubstantiation (transformation) and communion (unification).

[ 34 ] In everything which I present to you, my dear friends, I have no other goal than to share these things firstly with you. Everything that is to happen now will be based on the fact that, despite our communal confrontations which we know about, the tasks of our time will especially come out of a truly religious consciousness. We will speak about this further, tomorrow.

An Open Letter To Dr Rudolf Steiner

September 1921

Honourable Doctor!

After the devastating impressions of the last years which have gone through the German world, a longing has developed for religious renewal. It is true that on the whole, quite small circles have these longings which are really serious and alive. However, these are circles in which one can hope to find the power for how this can be developed. Some really strong will glows here in the youthful hearts waiting for the aim and leadership. There where one didn't dare to think about it not long ago, lectures are being held regarding the rebirth of the German nation, and one allows certain religious sounds to become agreeable even if one doesn't want to know anything about church life. In newspapers and magazines, and much more so in innumerable dialogues, there is a turn towards higher questions. The feeling that something new and great could come into the inner realm lives in a clear or less clear way in many of the best of us. As hopeful as we at times evoke this mood, at closer inspection we still discover a hopelessness, which is truly a call for mercy. Nearly superstitiously one waits in these circles for religious leaders, but one has no idea in which direction one is steered and vacillates between hope and a deep mistrust in one's own hope. Inspired, one celebrates soon the one and then the other which on the region of the inner life appears strong and safe to talk about, yet to which one has to admit shortly after, that one was disappointed and that the word of fulfilment is not mentioned again. One hopes for intuitions, does not know the at least where it should come from and which are the most believable, and confuses ever more dangerous tendencies of instinctive life with divine revelations. One regards the great personalities of the past, Fichte, Goethe, also Luther, and tries drawing inspiration from their work without really liberating contemporary solutions.

People look for substitutes in community feelings and community experiences and completely forget that each and every great soul had been given by community. There's a demand for a new "ritual" and they don't know that only a new spirit can bring a new ritual/worship, that the right spirit on its own can bring about a satisfactory form of worship from out of himself. People create all kinds of dance and play and enjoy the sure spirit of times gone by, expecting from this to create something which one can't create yourself but should create.

In this general hopelessness, which becomes ever more evident and could bring about a change of heart, Anthroposophy steps in and—multiply this hopelessness! Those who experience Anthroposophy for the first time, express much of the passionate rejection they experience. As one of those who have entered into such a circle where an understanding for your work can be found, I would here like to be the spokesman for these circles. In this way I would like to advise you to make something of the coherence and mood of these people, in order to help them understand Anthroposophic thought and actions better. As vividly as I am empathic on the one hand, how strange, yes, repulsive these people at first encounter Anthroposophy, so sure is my experience on the other hand that a fulfilment of the great, deep longing of our time can be achieved through the correct knowledge of anthroposophic accomplishments.

The people of whom, and for whom, I want to talk about here, long for a great purpose in life. They imagine this purpose of life, consciously or unconsciously, as a unified, powerful thought, as a singular soul-powerful feeing, which carries the whole of life and lift it up. Now the find Anthroposophy and discover an abundance of assertions in all kinds of fields, a mass of individual insights, big and small, which they initially don't know how to approach and towards which they feel helpless. It is as if they want to dangerously push everything away by saying 'One is necessary', which they still experience as a deep human need.

They want a clear, safe way to be indicated up high, which recommends itself to them convincingly and invitingly, a way they can walk forward to with a clear conscience and joyful courage. Now they hear of all kinds of exercises, which could and should be done, through which one laboriously acquires all kinds of abilities which do not seem essential and decisive to them—how one for example focuses your mind on the blossoming and withering of a plant in order to get an impression of the transience of life, the spirituality of a flower and so on. A confusing wealth of advice spreads itself out before them, on the one hand from the moral, known and obvious side and on the other hand, from the 'occult' strange or even questionable side. They would gladly feel free and great, striving at the pinnacle of humanity so to speak, but now they must find that some individuals with deep insights should be far ahead of them, and that they have no prospect in life to even come close to reaching them. As a result, they feel themselves pushed into a lower human class and even robbed of their human kingdom. They feel like an assassination attempt on their human dignity, even if they don't say it out loud.

Many of these people strongly feel that help can only come from a higher world. It is precisely here that Anthroposophy seems to be gradually thrown back on itself. It is for them as if people gradually want to and must push themselves higher, with unending effort and boredom while they long to be seized from above and be filled with new, powerful life forces from above.

Many of them have worked through a large part of knowledge of our time. Just from current science they have received powerfully chilling and paralysing impressions. And now also the realm of belief and the realm of knowledge needs transformation? Must their most precious and highest experiences of their inner soul realm be sacrificed for research and a descriptive 'science'? They fear that this will fall back into a dull intellectualism; they rear a falsification, even desecration of the inner life. It looks to them like a basic, dangerous underestimation of the deep distinction is presented between knowledge which appear through the senses and phenomena, and belief, the inner truth freely acknowledged. Not only a few of these people carried a strong knowledge within, that help must somehow be expected from Christ, not from churchlike Christianity, but from the correctly understood Christ himself. Yes, in individuals you find an instinctive awareness of the "living Christ" as the great helper of mankind. Now they are told that in Anthroposophy, Christ is regarded as the "regent of the sun" or that to begin with the two Jesus children in our time reckon with all kinds of extraordinary details; sincere claims which, as far as they had not found this quite repulsive initially, now in any case mean absolutely nothing and above all doesn't appear to be of help.

Some of them are also influenced by the "culture" of the last decades—the word "culture" itself has become so questionable that it can hardly be heard any more. They all look rather at everything else as a "new culture." Now they experience Anthroposophy penetrating into all outer areas, in architecture, the art of dance, which all want to renew our culture. There it appears that the power of humanity regarding religion as the main focus is pushed aside to a busyness and all kinds of outer work of vain distraction.

Above all, however, we must also remember those by whom the social question has been raised precisely by religious sentiment, becoming the mighty burning question of our time, and who can only through a new spirit, which grasps and truly fulfils humanity with a pure, strong brotherly mood make the salvation possible for the world. To them Anthroposophy seems neither simple nor warm, neither convincing nor contemporary or popular enough to somehow help humanity recover from their current main dilemma.

How much the present theological striving of anthroposophy has remained inadequate, I know all too well. During the last years I've had many hours of embarrassment about it, that this great spiritual movement has been regarded as failed by my theological colleague, in a spiritual and unfortunately also human way. In the above-mentioned mood I believe deeper reasons need to be looked for regarding this strong instinctive antipathy which anthroposophy meets in theologians, but also in other religious circles.

Let me at least indicate to ignorant readers—who can say one gets the clear impression that I am again being mistaken through Anthroposophy—that I believe I have the right to know what to expect from all these objections which I have to handle almost daily. I clearly see that the antipathies partly originate out of a false understanding of the tasks which Anthroposophy proposes, which is quite inclusive yet simultaneously humble, when many of its opponents think, partly out of an inadequate insight into the depth and character of the current spiritual crises, and out of a similar inadequate knowledge of the real possibilities for their solution. While you have up to now not according to my knowledge entered explicitly and in detail into this whole circle of concern, I believe that for many there is really a need for you to once and for all answer such questions. Particularly enlightening it could be as well, if you can express yourself regarding how you from your point of view, out of your abilities judge the actual present human being to have "religious impressions" at all. Does one not turn to soul powers which are dwindling relentlessly, when one in some old sense of "pure religious" way want to address current humanity? What exists for the future when people today still speak about a "religious experience" and impressions of God? How can powers, which make people susceptible for the higher worlds, be enlivened and in which way can they be renewed? How do you imagine an active religious proclamation in future? The main issue would be to hear what you have to say, how you see the current religious crisis from your point of view, and how Anthroposophy can and will contribute.

As always with immense gratitude and veneration.

Yours,

Friedrich Rittelmeyer.

Zweiter Vortrag

[ 1 ] Meine lieben Freunde! Gestern bin ich davon ausgegangen, zunächst wenigstens mit ein paar Worten anzudeuten, wie Anthroposophie selbst durchaus nicht religionsbildend auftreten kann, in keiner Weise unmittelbar eingreifen kann in die Entwickelung des religiösen Lebens, sondern nur, wie ich gesagt habe, mittelbar. Denn Anthroposophie muß ja ihrem Wesen nach eine freie Tat des Menschengeistes sein, sie muß beruhen auf einer freien Tat des Menschengeistes — wie die Naturwissenschaft selber, die allerdings nach der anderen Seite hingeht —, während das religiöse Leben beruhen muß auf dem Verkehr mit der Gottheit, mit der man sich verbunden weiß, und von der man sich auch im religiösen Leben abhängig weiß.

[ 2 ] So könnte zunächst ein ernster Abgrund klaffen zwischen demjenigen, was Anthroposophie der gegenwärtigen Zivilisation geben kann, und einer Befruchtung des religiösen Lebens. Nur vielleicht die Gesamtheit des hier zu Besprechenden wird Ihnen zeigen können, daß dieser Abgrund nicht besteht. Aber ich will schon heute darauf aufmerksam machen, wie das anthroposophische Leben selbst auch in den Wissenschaftsbetrieb so eingreift, daß dieses Eingreifen bereits eine religiöse Färbung hat.

[ 3 ] Es ist ja ganz ohne Zweifel, daß die gegenwärtige Welt für das Verhältnis des Menschen zum Kosmos und zu seiner irdischen Umgebung eben vom Agnostizismus beherrscht ist, und derjenige, der als religiöser Mensch das nicht würdigt, würde einen schweren, einen sehr schweren Irrtum begehen. Denn er würde gewissermaßen aus einer inneren Bequemlichkeit heraus stehenbleiben wollen bei dem Alten und würde nichts beitragen dazu, daß gerade das Ewige im Alten wirklich auch für die Erdenentwickelung erhalten bleiben kann. Diesem Irrtum geben sich ja leider in der Gegenwart sehr viele Menschen hin. Sie verschließen sich davor, daß wir in ein Zeitalter eintreten, in dem es einmal notwendig sein wird, überall hineinzuleuchten mit menschlicher Besonnenheit, mit zum Bewußtsein erwachter Erkenntnis. Würde man künstlich das religiöse Leben fernhalten von dieser Erkenntnis, so würde es — weil ja zweifellos die Erkenntnis die größere Autorität beanspruchen würde — in dieser Erkenntnis untergehen, wie ihm das schon einmal drohte im 19. Jahrhundert, als die materialistischen Erkenntnisse das religiöse Leben in einem gewissen Sinne vernichten wollten.

[ 4 ] Dasjenige, was ich damit gesagt habe, muß uns einfach gefühlsmäßig durchdringen, es muß uns klar sein; und wenn es uns klar ist, meine lieben Freunde, dann werden unsere Vorstellungen, wie ich sie jetzt hervorrufen muß, nicht so paradox erscheinen, wie sie vielleicht für das erste Anhören erscheinen könnten.

[ 5 ] Der Agnostizismus, das Ignorabimus, ist etwas, was herausentsprungen ist aus der naturwissenschaftlichen Denkweise der neuesten Zeit. Worauf beruht denn die Erkenntnis, die sich sagt: Ignorabimus, oder die sich zum Agnostizismus bekennt? Sie beruht auf etwas, mit dem sie durchaus recht hat; sie beruht nämlich darauf, daß der Mensch allmählich versucht hat, für seine Erkenntnis sein Seelenleben ganz auszuschalten. Es ist ja so, daß das Ideal der menschlichen Erkenntnis für den modernen Wissenschaftler, auch für den Historiker, das geworden ist, die Subjektivi und nur dasjenige, was er als das Objektive gelten läßt, zur Sprache bringen zu lassen. Damit aber wird der Erkenntnisprozeß, gerade auch für den geisteswissenschaftlich Erkennenden, ein durchaus an den physischen Leib des Menschen gebundener Prozeß. Bitte fassen Sie das, meine lieben Freunde, in allem Ernste auf. Der Materialismus hat nämlich recht, wenn er diejenige Erkenntnis, die ihm zugänglich ist, als etwas durch und durch nicht nur materiell Bedingtes, sondern sogar materiell Verlaufendes ansieht. Das, was wirklich geschieht zwischen dem Menschen, wenn er naturwissenschaftlich erkennt, und der Außenwelt, das geht vor zwischen den äußeren materiellen Dingen und ihrer Beziehung zu den Sinnesorganen, das heißt ihrer Beziehung zu dem materiellen physischen Leib. Der reale Erkenntnisprozeß in bezug auf die Erdenwelt ist ein materieller Prozeß bis in die letzten Phasen des Erkennens hinein. Und das, auszuschalten was der Mensch [beim Erkennen] erlebt, erlebt er nur als Zuschauer, er erlebt es, indem er mit seinem Seelisch-Geistigen «nebenhergeht», so daß der Mensch eigentlich durchaus im Recht ist, der den Erkenntnisprozeß materiell auffaßt und diese Auffassung als einzig und allein maßgebend in der Gegenwart anerkennt. Der Mensch als Zuschauer, der keinerlei Aktivität in sich hat — das ist ja oftmals schon von Leuten, die Naturwissenschaftler sind und darüber nachgedacht haben, erkannt und ausgesprochen worden.

[ 6 ] Sehen Sie, für diesen Erkenntnisprozeß, bei dem der Mensch eigentlich ein bloßer Zuschauer ist, fliegt alles aus der Realität heraus, was der Mensch in seinem seelischen Leben durchmacht. Der Mensch nimmt die äußeren Dinge wahr, er denkt über die äußeren Dinge, er erinnert sich an die äußeren Dinge, er nimmt allerdings auch wahr, wie in seine Erinnerungen, in seine Gedankenerinnerungen Gefühle und Willensemotionen hineinspielen, allein wie das geschieht, das weiß er nicht, weil er über den Ursprung der Gefühle und des Willens vollständig im Unklaren ist, so daß man für diese Erkenntnis, die in der Gegenwart allein anerkannt wird, nur das in Anspruch nehmen kann, was sich zwischen Wahrnehmen und Erinnerung zuträgt. Das aber ist bloß Bild, das läuft wie eine Parallelerscheinung neben dem realen materiellen Prozeß nebenher. Der materielle Prozeß ist die Realität, und das [Erkennen] läuft neben dem materiellen Prozeß nebenher.

[ 7 ] Wenn man ein Organ dafür hat, das richtig aufzunehmen, was in der Epoche, als das Mysterium von Golgatha herannahte, die Mysterienlehrer und die Mysterienschüler, und was in der Zeit, man kann sagen, durch drei Jahrhunderte, nachdem es sich abgespielt hat, die damals zu Gnostikern gewordenen Mysterienlehrer als ihre innerste Herzensüberzeugung ausgesprochen haben, dann kann man nicht anders, als sich dazu so verhalten, daß man sagen muß: Sie haben vorausgesehen, daß der Mensch dies einmal so erfahren wird, daß er nur Zuschauer der Welt ist, und daß selbst sein Erkenntnisprozeß gewissermaßen ohne Beteiligung seiner Seele abläuft. Diese Empfindung beherrschte durchaus als eine Grundstimmung das Mysterienwesen zur Zeit des Mysteriums von Golgatha.

[ 8 ] Wie kommen wir aber heute gegenüber dieser Erkenntnis mit ihrem Ignorabimus, mit ihrem Agnostizismus zurecht? Da komme ich eben auf dasjenige, was, wie gesagt, zunächst als ein Paradoxon erscheint. Die Erkenntnis ist dadurch, daß sie ein materieller Prozeß ist, eben auch gefesselt an die materielle Welt, während der Mensch h im Geiste empfindet, im Geiste aber ein bloßer Zuschauer ist. Wenn wir nun die christliche Anschauung auf diese ganze Erscheinung ausdehnen, dann kommen wir letzten Endes dazu, dieses Erkennen selbst in denjenigen Prozeß einzugliedern, den das christliche Anschauen von den verschiedenen menschlichen Vorgängen überhaupt hat. Wir kommen dazu, in dem Sinne, wie ich das gestern charakterisiert habe, das Erkennen unserer Zeit als die letzte Phase der menschlichen Sündhaftigkeit anzusehen, als die letzte Phase des menschlichen Fallens aus einem früheren Zustande [in die Sündhaftigkeit]. Erst dann haben wir aus einem religiösen Untergrunde her aus unsere heutige Wissenschaft begriffen, wenn wir sie als die letzte Phase der Äußerung des sündhaften Menschen ansehen, wenn wir sie in das Gebiet der Sünde versetzen können. Das ist dasjenige, was paradox erscheint. Aus der Sündhaftigkeit klingt heraus das Ignorabimus, aus der Sündhaftigkeit klingt heraus, religiös gesprochen, der Agnostizismus.

[ 9 ] Nur wenn wir so empfinden gegenüber der modernen Wissenschaftlichkeit, empfinden wir dieser Wissenschaftlichkeit gegenüber christlich. Dann aber — und das werden wir namentlich in den folgenden Tagen sehen - ergibt sich aus der Erfassung der Sündhaftigkeit der heutigen Wissenschaftlichkeit ein ganz notwendiger Weg, ein innerer menschlicher Weg zu dem, was als Gnade aufzufassen ist.

[ 10 ] Damit habe ich zunächst nur etwas angedeutet, was in den folgenden Tagen zur Ausführung kommen soll; denn man muß mitunter schon etwas anders vorgehen, als man es in der heutigen Wissenschaft gewohnt ist, wenn man diese Dinge sachgemäß auseinandersetzen will. Man muß gewissermaßen erst die äußeren Kreise ziehen und von da nach innen gehen, und nicht von Axiomen ausgehen und daraus Folgerungen ziehen.

[ 11 ] Damit ist nun auf etwas Reales zumindest im Menschen hingedeutet. Denn wenn wir einfach bei dem gewöhnlichen [Erkenntnis]erleben, das der heutige Wissenschaftler hat, stehenbleiben, dann bleiben wir ja im Bilde stehen. In dem Augenblick, wo wir im Bilde — und die ganze Wissenschaft von heute ist ja Bild — das Sündhafte [der modernen Wissenschaftlichkeit] fühlen, da erfassen wir mit einer Realität in uns selbst die Sache, da sind wir auf dem Wege, die Wissenschaftflichkeit] selbst in die Realität hineinzunehmen. Man muß dieses Gefühl entwickeln können, wenn man sich dazu aufschwingen will, die Frage nun so zu stellen, daß man auch etwas Reales dabei empfindet: Wie ist es im religiösen Sinne möglich, dasjenige, was der Mensch zunächst als Zuschauer erlebt, hineinzubringen in das Reale, damit das menschliche Leben hier auf der Erde nicht bloß ein außermenschliches, ein materielles ist und der Mensch sich als bloßer Zuschauer verhält, sondern damit der Mensch mit seinem wahren Wesen eine Wirkung auf dieses Materielle ausübt? Wann geht das innerliche Leben in eine äußere Realität über, so daß wirklich etwas entsteht durch das, was innerlich erlebt wird und der Mensch da nicht bloß Zuschauer ist?

[ 12 ] Sehen Sie, diese Frage versuchte man von alters her mit dem Wesen des Sakramentalismus zu beantworten, und man kommt nicht anders zur Erfassung des Wesens des Sakramentalismus, als wenn man von solchen Erwägungen ausgeht, wie ich sie angestellt habe. Da tritt uns zunächst eines entgegen im Menschen, was etwas anderes ist als der Gedanke, der beschaut, da tritt uns entgegen: das Wort.

[ 13 ] Das Wort ist ja für die heutige Wissenschaft eigentlich etwas Mysteriöses, etwas Geheimnisvolles; denn das Wort, das der Mensch äußert, es wird ja zugleich auch vom Menschen durch das Gehör wahrgenommen. Im Menschen ist der Anlaß vorhanden für das, was im Worte liegt, er bringt das Wort hervor, aber zugleich hört er sich auch selber. Im Auge, im Schvermögen, ist dieser Prozeß, das aktive und das passive Element, ganz zusammengedrängt, aber er ist auch da vorhanden, nur analysiert ihn heute noch keine Physiologie. Eigentlich ist er bei allen Sinnen vorhanden, aber in bezug auf das Hören und Sprechen sind die beiden Elemente, das Aktive und das Passive, deutlich voneinander getrennt. Und indem wir sprechen, verhalten wir uns allerdings nicht mehr als bloße Zuschauer zu unserem Leben, sondern indem wir sprechen, nehmen wir im Sprechen schaffend an unserem Leben teil, denn das Sprechen hängt gleichzeitig zusammen mit dem Atmungsprozeß. Dasjenige, was im Sprechen waltet, strömt über in den Atmungsprozeß. Indem wir einatmen, bringen wir den Atmungsdruck bis zu unserem Rückenmarkskanal; dadurch bewegt sich dieser Druck nach dem Gehirn zu und wirkt formend auf das Gehirnwasser. Im Atmungsprozeß liegt also dasjenige, was, von der Außenwelt her in uns einströmend, an uns selbst gestaltet. Die Atemluft ist zunächst draußen, sie dringt in uns, sie wirkt gestaltend auf unser Gehirnwasser und formt dadurch auch mit die halbfesten Teile des Gehirns. Wir begreifen das Gehirn nur so [richtig], wenn wir es nicht nur ansehen als im Menschen gewachsen, sondern es sehen in fortwährendem Verkehr mit der Außenwelt.

[ 14 ] In dieses Hereinströmen des Atems verweben wir nun das Wort, das wir selber aussprechen. Ich will diese Dinge zunächst nur andeuten, wie gesagt, ich will einen äußersten Kreis ziehen und dann immer mehr und mehr nach dem Inneren gehen. Indem sich unser Wort verwebt mit der Atemluft — was ja vom Alten Testament angedeutet wird als das dem Erdenmenschen den Ursprung Gebende: das Einblasen der Atemluft —, indem sich also unser Wort vereinigt mit dem, was in der Atemluft als das Göttliche gesehen wird, erleben wir das Wort als das Schaffende in uns selber. Wir nehmen vom Weltenprozeß etwas wahr, wo wir nicht bloß Zuschauer sind, sondern wo das, was in der Seele lebt, in unseren eigenen Leib hinunter schaffend wirkt.

[ 15 ] Wir sind da angekommen, wo wir mit Verständnis aussprechen können: Im Menschenanfange ist das Wort, und alles im Menschen wird mit durch das Wort geschaffen. — Studieren Sie einmal, was es bedeutet, wie der Mensch, indem er die Sprache lernt, gerade an der Sprache nach und nach seine physische Organisation herausgliedert. Wir sind noch nicht angekommen bei den Worten des JohannesEvangeliums selber, aber wir sind angekommen bei der Ausprägung von etwas dem Johannes-Evangelium Ähnlichem in der Organisation des Menschen. Da haben wir, wenn wir zunächst den Menschen betrachten, der sich geistig-seelisch darlebt, von ihm ausgehend das Wort, in den physischen Organismus einziehend und an ihm schaffend, und da haben wir vieles in diesem physischen Organismus, das im Laufe unseres Lebens in seiner Form sich entwickelt am Worte selber; denn wir sind so, wie wir uns am Worte entwickeln.

[ 16 ] Was die Sprache für den Menschen bedeutet, das kann eigentlich nur geisteswissenschaftlich in seiner vollen Tiefe studiert werden. Wir haben ja schon im Sinne des Testamentes eine Verwebung des Wortes mit demjenigen, was den Menschen als das erste Göttliche durchzieht, dem Atmungsprozeß. Das bloße Denken, das in der Zuschauersphäre waltet, ist da hineingedrängt in das Schaffende. Indem das Denken übergeht zum Wort, bemächtigt sich das Göttliche dieses Denkens; es ist, man möchte sagen, die Vergöttlichung des Denkens, die in dem Worte eintritt. Und wenn man sich bewußt ist, daß man in dem Worte etwas mehr hat als das Sprechen, dann wird das Wort wie etwas, wodurch der Mensch schon die erste Verbindung, den ersten Verkehr mit dem Göttlichen gewahr wird an seinem eigenen Verhalten, an demjenigen Verhalten, das wie ein Verdichten, wie ein in das Fühlen getauchtes Denken ist. Und weil das gewissermaßen ein Weg ist von der Subjektivität des Denkens zur Objektivität, haben wir dann die Möglichkeit, daß in das Wort etwas einfließt, das geistig objektiv ist. Daran knüpft sich die Vorstellung, daß im Worte mehr gegeben sein kann als im bloß vom Menschen erzeugten Denken, daß in das Wort ein Göttliches einfließen kann, und daß sich im Wort gewissermaßen durch den Menschen das Göttliche ausspricht, daß die Botschaft von dem Göttlichen in dem Worte liegen kann.

[ 17 ] Und so haben wir das erste Element, das den Menschen auf seinem Wege aus sich selbst heraus zur Umwelt führt, durchtränkt von dem Göttlichen in dem Worte. So etwa wurde das Wort des Evangeliums empfunden, daß einströmt ein Göttliches in dieses Wort des Evangeliums, das wir nachfühlen können an der schöpferischen Tätigkeit des Wortes an uns selber; und wir haben das erste Element von dem, wie der Mensch kultusartig übergeht aus seinem Subjektiven zum Objektiven.

[ 18 ] Nun blicken wir auf dasjenige hin, was der Mensch über die Welt nicht denkt, sondern auf das, was er in der Welt tut. Blicken wir auf das menschliche Handeln. Dieses menschliche Handeln wird durch den neueren Materialismus heute selten im richtigen Lichte gesehen. Wiederum kann ich Ihnen fürs erste nur andeuten, um was es sich dabei eigentlich handelt; wir werden, wie gesagt, auf diese Dinge weiter eingehen.

[ 19 ] Wenn Sie sich folgende Vorrichtung vorstellen: um eine Rolle ein Seil, hier ein Gewicht, hier ein etwas größeres Gewicht angelegt (siehe Tafel 1), zwei verschieden große Gewichte, so wird durch die Schwerkraft das Seil hier (links) heruntergezogen, und es wird das andere Gewicht hier (rechts) hinaufgezogen. Dasselbe können Sie auch ausführen, wenn Sie selber hier (links am Seil) ziehen, und zwar stärker, als das Gewicht hier (rechts) zieht. Sie können also etwas selber ausführen, was in einem objektiven Vorgang auch geschehen kann. Das eine Mal, wenn Sie hier ein größeres Gewicht anhängen, geschieht der Vorgang, ohne daß Sie dabei sind, aber wenn Sie dabei sind, können Sie das Gewicht ersetzen. Dasjenige, was in der Außenwelt geschieht, kann durchaus auch ohne Sie geschehen.

[ 20 ] Nun ist das allerdings ein Vorgang in der anorganischen Natur. Wer aber das studiert, was der Mensch in der Außenwelt vollbringt, der kommt darauf, daß das, was durch den Menschen in der Außenwelt geschieht, eigentlich so geschieht, daß es ganz aus den geistigen Zusammenhängen hervorgeht, und daß der Leib des Menschen nur die Gelegenheit dazu abgibt, daß er dabei sein kann. Wir sind nämlich — während wir bei dem Welterkennen mit unserem GeistigSeelischen Zuschauer sind — bei unserem Handeln so dabei, daß unser Leib nur eine Zutat ist. Was in unserem Leibe vor sich geht, das sind Bewegungsprozesse, Ernährungsprozesse, Auflösungsprozesse und so weiter; das, was in unserem Leibe vor sich geht, ist eine Zutat, etwas, was hinzukommt zu dem, was objektiv geschieht. Unser Leib nimmt eigentlich an unseren Handlungen nicht teil; wir verstehen unsere Handlungen nur, wenn wir sie abgesondert von unserem Leib verstehen. Geradeso wie wir im Erkenntnisprozeß, materialistisch aufgefaßt, etwas haben, was uns zum Zuschauer macht, so haben wir im Prozeß des Handelns für die Welt, in dem Prozeß des Handelns, der sich abspielt in der Welt, etwas, woran unser Leib gar keinen Anteil nimmt. Die Prozesse, die sich im Leibe abspielen, bleiben ohne eine kosmische Bedeutung, [ebenso] wie das materialistische Erkennen zunächst keine kosmische Bedeutung hat. Der Mensch bleibt mit seinem Materiellen in seinem Handeln, wenn es sich nur auf das Irdische bezieht, wie ein Eremit in der Welt stehen, er hat keine Beziehung zu etwas außer ihm. Sucht er diese Beziehung, dann muß er in seine Handlungen selbst schon etwas von seinem eigenen Geiste hineinmischen, dann muß er die Handlungen so vollziehen, daß sie nicht abgesondert von ihm nur da sind, wie alle irdischen Handlungen, dann muß er seine Gedanken und seine Empfindungen in die Handlungen hineinleben, dann muß die Handlung zum Zeichen werden für das, was er da hineinlebt. Dann ist sie aber Opferhandlung, dann ist sie das Opfer.

[ 21 ] Sehen wir auf das Erkennen hin, so sehen wir das Objektivwerden des Erkennens in dem Geltendmachen der Botschaft im Worte; sehen wir auf das Handeln hin, dann haben wir das Objektivwerden des Handelns, das Hinausziehen des Handelns aus dem Menschen allein, in der Opferhandlung gegeben. Hier haben wir zunächst die Beziehung des Menschen zur äußeren Welt real insofern gegeben, als sie aus dem geistig-seelischen Menschen heraus entsteht. Aus dem geistig-seelischen Menschen heraus quillt dann auch die Imagination — gegenüber dem Worte, das man nicht mehr als menschliche, sondern als göttliche Offenbarung empfindet, und gegenüber der Opferhandlung, die nicht mehr als eine Handhabung der menschlichen Welt empfunden wird, an der der Mensch unbeteiligt ist, sondern [als eine solche], an der seine Gedanken, seine Gefühle mit beteiligt sind; diese empfindet er wiederum mit seinem inneren Erleben.

[ 22 ] Die andere Beziehung, die der Mensch hat gegenüber der Außenwelt, tritt uns entgegen in der Ernährung des Menschen. Wir haben ja drei Beziehungen eigentlich zur Außenwelt: die durch die Sinne in der Wahrnehmung, die durch die Atmung und die durch die Ernährung. Alles übrige ist auf diese zurückzuführen. Die Atmung steht aber eigentlich zwischen der Wahrnehmung und der Ernährung mitten drinnen, denn man könnte sagen, die Atmung ist halb Wahrnehmung und halb Ernährung. Es ist nicht zu leugnen, der Atmungsprozeß steht zwischen Wahrnehmungs- und Ernährungsprozeß drinnen. Sie sehen, er ist zugleich mit dem Wahrnehmungsund mit dem Ernährungsprozeß verbunden. Die Atmung ist die Synthese zwischen Wahrnehmung und Ernährung.

[ 23 ] Unsere Physiologie betrachtet die Ernährung ja durchaus falsch. Unsere Physiologie meint, wir nehmen die Nahrung zu uns. Wir sondern aus der Nahrung dasjenige aus, was für uns geeignet ist und stoßen das andere ab. So ist es aber nicht. Daß wir das Substantielle aufnehmen, ist bloß Begleiterscheinung. Der Lebensprozeß besteht durchaus darin, daß wir uns eigentlich fortwährend gegen dasjenige wehren, was durch die Einnahme eines Nahrungsmittels in uns bewirkt wird. Wir essen, wir trinken — dadurch geschieht etwas, was wahrhaftig sehr tief unter unserem Bewußtsein, unter unserem bewußten Seelenleben liegt. Dasjenige, was da geschieht, ist ein fortwährendes Abwehren. Und in diesem physisch-physiologischen Prozeß des Abwehrens liegt der eigentliche Lebensprozeß der Ernährung. Der Lebensprozeß der Ernährung ist ein Abwehrprozeß. Erst wenn man einsehen wird, wie der Organismus darauf hinorganisiert ist, die Anregung zu einer Abwehr zu erhalten - damit er die Abwehr haben kann, muß natürlich die Anregung dazu da sein —, erst wenn man einsehen wird, daß in der Abwehr einer von außen kommenden [Substanz die] Anregung zu dem Lebensprozeß der Ernährung liegt, wird man die Ernährung richtig verstehen können. Man hat es beim Ernähren mit einem Abwehrprozeß zu tun, bei dem das Aufnehmen von Substanzen nur als eine Begleiterscheinung [anzusehen ist], durch die in die feinsten Verfaserungen des Wesens des Menschen von außen die Anregungen zu Widerständen geleitet werden, damit bis in die äußeren Peripheriegebiete [des Organismus] diese Abwehr Platz greifen kann. Erst in diesem Abwehren liegt der wirkliche Lebensprozeß der Ernährung, so daß dasjenige, was der gewöhnliche irdische Ernährungsprozeß des Menschen ist, eigentlich ein Abwehren des Irdischen ist. Das Irdische dringt als Nahrungsmittel in den Menschen ein, der Mensch muß es aufnehmen, aber es ist dies ein Prozeß des Abwehrens.

[ 24 ] Das ist die Wirklichkeit, aber so sieht der Mensch in der Wissenschaft das Ganze eigentlich nicht an. Was geschieht aber in diesem Abwehren? Da geschieht etwas, was ganz außerhalb des menschlichen Bewußtseins liegt. Wenn nämlich der Mensch die Nahrung aufnimmt, so ist ja die Nahrung eigentlich ein Prozeß [der Außenwelt]. Jeder Stoff ist eigentlich ein konzentrierter, gedrosselter Weltenprozeß. Prozesse der Außenwelt nehmen wir in uns auf, wir wehren sie ab, aber indem wir sie abwehren, entsteht ja der Gegenprozeß: Der Prozeß der Außenwelt wird in etwas ganz anderes verwandelt und dieses Verwandeln geschieht in uns. Das äußere Materielle wird in uns verwandelt. Und was wird daraus? Es wird in uns ein Geistiges. Das ist es, was gewöhnlich nicht gesehen wird, daß der Mensch eigentlich in seinem Verdauungsprozeß in der Verwandlung der Außenwelt bis zu der Vergeistigung der äußeren materiellen Prozesse geht. In der äußeren Natur spielen sich eben die Weltenprozesse ab, es spielen sich die Weltenprozesse im Fragment ab, sagen wir, bis zur Entstehung des Kornes, bis zur Entstehung der anderen Dinge, die als Nahrungsmittel aufgenommen werden. Dasjenige, was da in der Außenwelt entsteht, das wird erst verwandelt im Innern des Menschen, das ist dadurch auf dem Wege nach dem Geistigen hin. In der Außenwelt kann es sich nicht bis zum Geistigen hin verwandeln, erst im Innern des Menschen kann es sich bis zum Geistigen hin verwandeln. Das ist einfach eine objektive Tatsache, die ich Ihnen hier erzähle, nichts anderes. Aber das, was ich Ihnen da auseinandersetze, spielt sich außerhalb der menschlichen Gedankenwelt ab. Es spielt sich in den tieferen Regionen des menschlichen Wollens und nur teilweise in den Gefühlsregionen ab. Nur gewisse Partien des Gefühlslebens und das Wollen nehmen teil an dem [Ernährungs]-prozeß, den ich eben geschildert habe. Der Gedankenprozeß nimmt daran nicht teil, der geht gerade den entgegengesetzten Weg, durch das Wort geht er hinunter in die Gestaltung. Hier unten haben wir, wieder von außen kommend und in der entgegengesetzten Richtung drängend wie der Gedankenprozeßweg, den Verwandlungsprozeß.

[ 25 ] Will man den Verwandlungsprozeß so hinstellen vor den Menschen, daß der Mensch ihn anschaut, wie er die äußere Welt anschaut, so muß man in die äußere Welt etwas hinstellen, was in der äußeren Welt sonst nicht geschieht, sondern nur im Menschen sich abspielt. Damit aber hat man in die äußere Welt eine sakramentale Handlung hingestellt, etwas, was nicht in Naturerscheinungen verläuft, was aber im Menschen als des Menschen Geheimnis sich abspielt. Will man dasjenige, was zum innersten Wesen des Menschen gehört, auf dem Gebiet, das wir eben charakterisiert haben, vor den Menschen hinstellen, so hat man die Wandlung, die Wandlung des Brotes und des Weines in Leib und Blut [Christi], man hat die Transsubstantiation. Die Transsubstantiation ist nicht eine Erfindung innerhalb der äußeren Welt, die Transsubstantiation ist das Hinausstellen desjenigen in die Außenwelt, was im tiefsten menschlichen Innern wirklich sich vollzieht. Wir schauen in der Transsubstantiation dasjenige, was wir nicht in der Außenwelt schauen können, weil die Außenwelt ein Fragment des Daseins ist, nicht eine Totalität; und wir fügen im Sakramente dasjenige zu der Außenwelt hinzu, was im Reiche der Natur erst vollzogen wird innerhalb des Menschen.

[ 26 ] Das, meine lieben Freunde, ist der ursprüngliche Begriff des Sakramentes, daß zu dem Phänomen der Außenwelt hinzugefügt wird dasjenige, was im Innern des Menschen nicht zum Bewußtsein kommt, weil der Mensch es nicht erkennt, sondern [unbewußt] erlebt, was aber im Zeichen in die Außenwelt hineingestellt werden kann. Und so muß der Mensch, indem er die Transsubstantiation vollzieht, etwas, was mit dem innersten Wesen seines Selbst unbewußt zusammenhängt, im Zeichen mitempfinden. Er bahnt in der Tat den Verkehr an mit dem Geiste der Außenwelt dadurch, daß er die Verwandlung, welche sich sonst hinter dem Schleier des Erinnerungsvermögens in seinem Innern vollzieht, als Sakrament hinstellt.

[ 27 ] Damit aber haben wir noch nicht dasjenige erfaßt, was nun im Menschen als Höchstes sich vollzieht, wir haben nur erfaßt das Geistigwerden des Materiellen im Menschen, die Verwandlung, die Transsubstantiation. Dasjenige, was da im Menschen als objektiver Vorgang geschieht, das vollzieht sich, ich möchte sagen, nur durch einen dünnen Schleier von unserem Bewußtsein getrennt, hinter unserem Bewußtsein. Denn von dieser Seite her wird in jedem Augenblick unseres Lebens unser Ich angefacht. Wir tauchen unter in diese verwandelte Materie, und indem wir die Stoffe der Außenwelt aufnehmen und unser Lebensprozeß darin besteht, sie zu verwandeln, indem wir mit unserem Geistig-Seelischen untertauchen in diese Verwandlung der Außenwelt, hat unser Ich fortwährend Nahrung, wird unserem Ich fortwährend nahegelegt die Vereinigung mit der durch diesen Prozeß verwandelten Substanz. Die Vereinigung mit der Substanz nach ihrer Verwandlung stellt die Ichwerdung des uns im Menschen zugänglichen Geistigen dar. Nehmen wir auch dies sakramental. Stellen wir es sakramental vor uns hin, so ist es das Sakrament, an dem der Mensch teilnimmt, wenn die Materie so vorgestellt wird, daß sie nur Zeichen ist; wenn sie transsubstantiiert ist, vereinigt sich der Mensch mit ihr, und wir haben damit das vierte Glied desjenigen, was im Kultus als sakramentales Zeichen den Zusammenhang des Menschen mit der Welt darstellen kann.

[ 28 ] Sehen wir auf den Menschen hin, insofern er sich der Außenwelt hingibt, so haben wir dasjenige, was, ich möchte sagen, [als] die Realisation des Erkenntnisprozesses [im Geiste erlebt] wird, im Worte; und in der Opferhandlung, die ja in dem, was sie äußerlich ist, nur Zeichen ist, haben wir alles das angedeutet, was der Mensch [geistig-seelisch mit seinen Handlungen] verbinden kann. Sehen wir auf den Menschen hin, indem er aufnehmend aus der Außenwelt ist, so haben wir die Verkündigung der Botschaft im Worte und die Opferhandlung; sehen wir auf den Menschen hin, der fortwährend aus sich heraus das Geistige gebiert, dann haben wir dies vergegenwärtigt in den sakramentalen Handlungen der Transsubstantiation und der Kommunion.1Der vorangehende Textabschnitt ist in der Übertragung des Stenographen sehr lückenhaft und mußte deshalb durch Einfügungen der Herausgeber ergänzt werden.

[ 29 ] Damit haben wir aber die Möglichkeit, einen realen Sinn nun auch mit demjenigen zu verbinden, was der Mensch in bezug auf sein ganzes Handeln sonst in der Außenwelt ist. Das Handeln sondert sich von ihm ab, sein eigener Körper geht neben ihm her. In der Transsubstantiation wird gerade das zum Geschehen gemacht, was in der Außenwelt sich nicht vollzieht, weil die Außenwelt nur ein Fragment des möglichen Geschehens ist. Und in der Kommunion verbindet sich der Mensch mit demjenigen der Außenwelt, mit dem er sich durch den Gedanken nicht verbindet. Objektive Vorgänge haben wir in der Transsubstantiation und in der Kommunion. Wir haben den Menschen dadurch hineingestellt in physisch-seelisch-geistiger Art in den Weltenzusammenhang. Wir haben aufgehört, in dem Menschen etwas von der Welt Abgesondertes, einen Eremiten des Daseins zu sehen; wir haben angefangen, in ihm zu sehen ein Glied der ganzen Welt. Wir haben gelernt, die Welt als Materialität anzusehen, aber da, wo wir sie als Fragment erkannt haben, sie so anzusehen, daß der Grundboden das Geistige ist, auf dem sich dieses Materielle ausnimmt nur als ein Teil, sich vergeisugend und vollendend; und wir haben den göttlichen Kreislauf, der sich im Äußeren und Inneren des Menschen vollzieht, vor uns hingestellt... [Lücke]

[ 30 ] Das wollten diejenigen vor die Menschen hinstellen, die sagten: Des Menschen physisch-seelisch-geistiges Verhältnis zum Universum kann euch vergegenwärtigt werden durch Sakramente: erkennend durch das Wort und durch die Opferhandlung, handelnd durch die Transsubstantiation und die Kommunion. Ihr könnt euch einleben in ein Zusammenleben mit der ganzen Welt, indem ihr dasjenige, was sonst auf zwei Hälften im Menschen verteilt ist, das Geistig-Seelische, das bloß zuschaut, und das Körperliche, das bloß eine Zugabe ist zu den äußeren Handlungen, [vereinigt], indem ihr dasjenige, was sonst bloß Zuschauer bleiben will in dem Verhältnis des Menschen zur Außenwelt, sakramentalisiert in der Botschaft vom Wort, im Evangelium — das aus dem «Angelum», aus dem Orte der geistigen Welt dringt — und in der Opferhandlung; und indem ihr dasjenige, was der Mensch in seinem Innern erlebt und wodurch der Mensch erst vollständig wird, sakramentalisiert in der Transsubstantiation, der Verwandlung, und indem ihr dann den Menschen hineingliedert in dieses Ganze in der Kommunion, in der Vereinigung. Da habt ihr einen realen Prozeß, der nun kein bloßer Erkenntnisprozeß ist, sondern ein Prozeß, an dem ihr hängt mit eurem Fühlen und Wollen, während der Erkenntnisprozeß im kalten, eisigen Gebiet des bloß Abstrakten verläuft.

[ 31 ] Dasjenige, was in der Erkenntnis eisig verläuft, wird gewissermaßen erwärmt in der Botschaft des Wortes und in der Opferhandlung. Dasjenige aber, was durch Überhitzung nicht mehr im Bewußtsein leben kann, weil die Hitze das Bewußtsein betäubt und es dadurch im Innern nicht wahrgenommen werden kann, das kann, wenn das Phänomenon zum Noumenon erhoben wird, das heißt wenn an die Stelle des äußeren Vorganges, der mit den Sinnen angeschaut wird, der dem menschlichen Wesen selbst nachgebildete äuRere Prozeß der sakramentalen Handlung gesetzt wird, in der sakramentalen Handlung angeschaut werden als dasjenige, was hinter der Natur ist, und was durch nichts anderes hervorgebracht werden kann, was aber eine objektive Bedeutung in der Welt hat, weil es das Geschehen des menschlichen Lebens selber in den Kosmos hineinstellt.

[ 32 ] Damit aber haben wir etwas gegeben, was unseren heutigen abstrakten Erkenntnisprozeß ins reale Leben hineinstellt. Nun bleibt nur noch eine Frage übrig, die eine ganz bedeutsame Frage ist. Einsehen können wir, daß im Menschen etwas geschieht durch das Wort, denn das Wort wirkt hinunter in seine Körperlichkeit und der Mensch gestaltet sich in dem Worte. Einsehen können wir auch das, daß durch die Opferhandlung etwas im Innern des Menschen geschieht, denn die Opferhandlung vollzieht der Mensch so, daß er nicht bloß dasjenige zurückhält, was in seinem Leibe liegt, sondern daß er Gefühl und Willen an dieser Opferhandlung beteiligt. Dadurch aber wird ein irdisches Geschehen des Leibes an ein außerirdisches Geschehen gebunden. Das kann eingesehen werden. Tatsächlich gehen bei der Opferhandlung ganz andere Gefühle vor sich durch die Vorgänge, die an der Opferhandlung erlebt werden, als bei der gewöhnlichen äußeren Handlung. Es geschieht ein Abdämpfen des das Bewußtsein betäubenden innerlich im Menschen Getragenen. Und wenn wir uns so sagen können: da geschieht etwas im Menschen -, da entsteht die große Frage, die wir uns in der nächsten Zeit zu beantworten haben: Tritt eigentlich dieses Geschehen, das zunächst ein unabhängiges Geschehen ist, auch herein in den Gang des äußeren Geschehens? Ist es auch ein Weltgeschehen? Und ebenso müssen wir uns fragen: Die 'Transsubstantiation und die Kommunion, die zunächst etwas sind, was der Mensch erlebt an einer äußeren Handlung, die aber Zeichen sind und daher heraustreten aus dem Gang der Naturereignisse —, treten sie wiederum irgendwo hinein in den Gang der Naturereignisse? Sind sie außerhalb des Menschen etwas Reales? Dies ist der andere Bestandteil der Frage. Wie gesagt, diese Frage wird uns in den nächsten Tagen zu beschäftigen haben.

[ 33 ] Sie werden schon bemerkt haben: damit ist dasjenige vor Sie hingestellt, was die vier Hauptglieder des Meßopfers sind, die ja durchaus beruhen auf Urbewußtseinserfahrungen der Mysterien. Die vier Hauptbestandteile des Meßopfers sind ja: das Lesen des Evangeliums, das Offertorium (Opferung), die Transsubstantiation (Wandlung) und die Kommunion (Vereinigung).

[ 34 ] Ich habe bei alledem, was ich Ihnen vortrage, meine lieben Freunde, kein anderes Ziel, als Ihnen diese Dinge zunächst mitzuteilen. Alles, was nun werden soll, wird darauf beruhen, daß eben in unseren gemeinschaftlichen Auseinandersetzungen aus dem, was man wissen kann, dasjenige herausgeholt wird, was gerade nach den Aufgaben unserer Zeit aus einem wahrhaft religiösen Bewußtsein heraus zu geschehen hat. Davon wollen wir morgen weiter sprechen.

Friedrich Rittelmeyer

Offener Brief an Herrn Dr. Rudolf Steiner

September 1921

Hochverehrter Herr Doktor!

Durch die deutsche Welt geht, nach den erschütternden Eindrücken der letzten Jahre, ein Sehnen nach religiöser Erneuerung. Zwar sind es, auf das Ganze gesehen, recht kleine Kreise, in denen dies Sehnen wirklich ernst und lebendig ist. Aber es sind Kreise, in denen man Kräfte zu finden hoffen kann, wie man ihrer für den inneren Aufbau bedarf. Manches hohe starke Wollen glüht hier in jugendlichen Herzen und wartet auf Ziel und Führung. Dort, wo man früher nicht von ferne daran hätte denken dürfen, werden Vorträge gehalten über die innere Wiedergeburt des deutschen Volkes, und man läßt sich entschiedene religiöse Klänge gern gefallen, wenn man auch von Kirchentum allermeist nichts wissen will. Auch in Zeitungen und Zeitschriften, viel mehr aber noch in ungezählten Einzelgesprächen, wendet sich das Interesse höheren Fragen zu. Die Empfindung, daß im Reich der Innerlichkeit etwas Neues, Großes kommen sollte und kommen könnte, lebt deutlicher oder dumpfer in vielen der Besten. So hoffnungsvoll uns solche Stimmungen manchmal anwehen, so entdeckt man doch bei näherem Zuschen eine Ratlosigkeit, die wahrhaft zum Erbarmen ist. Fast abergläubisch wartet man in diesen Kreisen auf religiöse Führer, aber man hat keine Ahnung, wohin man geführt werden wird und schwankt zwischen Hoffnung und tiefem Mißtrauen gegen die eigne Hoffnung. Man feiert begeistert bald den einen bald den anderen, der auf dem Gebiet der Innerlichkeit stark und sicher zu reden scheint, erkennt aber schon nach kurzer Zeit enttäuscht, daß das Wort der Erfüllung doch wieder nicht gesprochen wurde. Man hofft auf Intuitionen, weiß nicht im geringsten, woher sie kommen sollen und welches ihre Beglaubigung ist, und verwechselt immer gefährlicher die Neigungen des Trieblebens mit göttlichen Offenbarungen. Man schaut auf die Großen der Vergangenheit, Fichte, Goethe, auch Luther, und vermag doch aus ihren Werken nur Anregungen, keine wirklich befreienden zeitgemäßen Lösungen zu gewinnen. Man sucht Ersatz in allerlei Gemeinschaftsgefühlen und Gemeinsamkeitserlebnissen und vergißt völlig, daß je und je von den großen Einzelnen der Gemeinschaft eine Seele gegeben worden ist. Man fragt nach einem neuen «Kultus» und weiß nicht, daß nur ein neuer Geist einen neuen Kultus bringen kann, daß der rechte Geist allein ganz von selbst zum befriedigenden Kultus führen wird. Man erbaut sich an allerlei Tanz und Spiel, genießt darin den starken sicheren Geist vergangener Zeiten, und erwartet davon, was man nicht selbst schaffen kann, aber schaffen sollte.