Soul Economy

Body, Soul and Spirit in Waldorf Education

GA 303

IX. Children from the Seventh to Tenth Years

31 December 1921, Stuttgart

An important and far-reaching change takes place when children begin to lose their milk, or baby, teeth. This is not just a physical change in the life of a human being, but the whole human organization goes through a transformation. A true art of education demands a thorough appreciation and understanding of this metamorphosis. In our previous meetings, I spoke of the refined body of formative forces, the ether body. These forces are in the process of being freed from certain functions during the time between the change of teeth and puberty. Previously, the ether body worked directly into the physical body of the child, but now it begins to function in the realm of a child’s soul. This means that the physical body of children is held from within in a very different way than it was during the previous stage. The situation then was more or less as described by those of a materialistic outlook, who see the foundation of the human psyche in the physical processes of the human body. They see the soul and spirit of children as emanating from the physical and related to it much as a candle flame is related to the candle. And this is more or less correct for a young child until the change of teeth. During the early years, the soul and spiritual life of the child is completely connected to the physical and organic processes, and all of the physical and organic processes have a soul and spiritual quality. All of the shaping and forming of the body at that age is conducted from the head downward. This stage concludes when the second teeth are being pushed through. At this time, the forces working in the head cease to predominate while soul and spiritual activities enter the lower regions of the body—the rhythmic activities of the heart and breath. Previously, these forces, as they worked especially in the formation of the child’s brain, were also flowing down into the rest of the organism, shaping and molding and entering directly into the physical substances of the body. Here they gave rise to physical processes.

All this changes with the coming of the second teeth, and some of these forces begin to work more in the child’s soul and spiritual realm, affecting especially the rhythmic movement of heart and lungs. They are no longer as active in the physical processes themselves, but now they also work in the rhythms of breathing and blood circulation. One can see this physically as the child’s breathing and pulse become noticeably stronger during this time. Children now have a strong desire to experience the emerging life of soul and spirit on waves of rhythm and beat within the body—quite subconsciously, of course. They have a real longing for this interplay of rhythm and beat in their organism. Consequently, adults must realize that whatever they bring to children after the change of teeth must be given with an inherent quality of rhythm and beat. Everything addressed to a child at this time must be imbued with these qualities. Educators must be able to get into the element of rhythm to the degree that whatever they present makes an impression on the children and allows them to live in their own musical element.

This is also the beginning of something else. If, at this stage, the rhythm of breathing and blood circulation is not treated properly, harm may result and extend irreparably into later life. Many weaknesses and unhealthy conditions of the respiratory and circulatory systems in adult life are the consequences of an improper education during these early school years. Through the change in the working of children’s ether body, the limbs begin to grow rapidly, and the life of the muscles and bones, including the entire skeleton, begins to play a dominant role. The life of muscles and bones tries to become attuned to the rhythms of breathing and blood circulation. At this stage, children’s muscles vibrate in sympathy with the rhythms of breathing and blood circulation, so that their entire being takes on a musical quality. Previously, the child’s inborn activities were like those of a sculptor, but now an inner musician begins to work, albeit beyond the child’s consciousness. It is essential for teachers to realize that, when a child enters class one, they are dealing with a natural, though unconscious, musician. One must meet these inner needs of children, demanding a somewhat similar treatment, metaphorically, to that of a new violin responding to a violinist, adapting itself to the musician’s characteristic pattern of sound waves. Through ill treatment, a violin may be ruined for ever. But in the case of the living human organism, it is possible to plant principles that are harmful to growth, which increase and develop until they eventually ruin a person’s entire life.

Once you begin to study the human being, thus illuminating educational principles and methods, you find that the characteristics just mentioned occupy roughly the time between the change of teeth and puberty. You will also discover that this period again falls into three smaller phases. The first lasts from the change of teeth until approximately the end of the ninth year; the second roughly until the end of the twelfth year; and the third from the thirteenth year until sexual maturity.

If you observe the way children live entirely within a musical element, you can understand how these three phases differ from one another. During the first phase, approximately until the end of the ninth year, children want to experience everything that comes toward them in relation to their own inner rhythms—everything associated with beat and measure. They relate everything to the rhythms of breath and heartbeat and, indirectly, to the way their muscles and bones are taking shape. But if outer influences do not synchronize with their inner rhythms, these young people eventually grow into a kind of inner cripple, although this may not be discernible externally during the early stages.

Until the ninth year, children have a strong desire to experience inwardly everything they encounter as beat and rhythm. When children of this age hear music (and anyone who can observe the activity of a child’s soul will perceive it), they transform outer sounds into their own inner rhythms. They vibrate with the music, reproducing within what they perceive from without. At this stage, to a certain extent, children have retained features characteristic of their previous stages. Until the change of teeth children are essentially, so to speak, one sense organ, unconsciously reproducing outer sensory impressions as most sense organs do. Children live, above all, by imitation, as already shown in previous meetings. Consider the human eye, leaving aside the mental images resulting from the eye’s sensory perceptions, and you find that it reproduces outer stimuli by forming afterimages; the activity leading to mental representation takes hold of these aftermages. Insofar as very young children inwardly reproduce all they perceive, especially the people around them, they are like one great, unconscious sense organ. But the images reproduced inwardly do not remain mere images, since they also act as forces, even physically forming and shaping them.

And now, when the second teeth appear, these afterimages enter only as far as the rhythmic system of movement. Some of the previous formative activity remains, but now it is accompanied by a new element. There is a definite difference in the way children respond to rhythm and beat before and after the change of teeth. Before this, through imitation, rhythm and beat directly affected the formation of bodily organs. After the change of teeth, this is transformed into an inner musical element.

On completion of the ninth year and up to the twelfth year, children develop an understanding of rhythm and beat and what belongs to melody as such. They no longer have the same urge to reproduce inwardly everything in this realm, but now they begin to perceive it as something outside. Whereas, earlier on, children experienced rhythm and beat unconsciously, they now develop a conscious perception and understanding of it. This continues until the twelfth year, not just with music, but everything coming to meet them from outside.

Toward the twelfth year, perhaps a little earlier, children develop the ability to lead the elements of rhythm and beat into the thinking realm, whereas they previously experienced this only in imagination.

If, through understanding, you can perceive what happens in the realm of the soul, you can also recognize the corresponding effects in the physical body. I have just spoken of how children want to shape the muscles and bones in accordance with what is happening within the organs. Now, toward the twelfth year, they begin to be unsatisfied with living solely in the elements of rhythm and beat; now they want to lift this experience more into the realm of abstract and conscious understanding. And this coincides with the hardening of those parts of the muscles that lead into the tendons. Whereas previously all movement was oriented more toward the muscles themselves, now it is oriented toward the tendons. Everything that occurs in the realm of soul and spirit affects the physical realm. This inclusion of the life of the tendons, as the link between muscle and bone, is the external, physical sign that a child is sailing out of a feeling approach to rhythm and beat into what belongs to the realm of logic, which is devoid of rhythm and beat. This sort of discovery is an offshoot of a real knowledge of the human being and should be used as a guide for the art of education.

Most adults who think about things in ways that generalize, whether plants or animals (and as teachers you must introduce such general subjects to your students), will recall how they themselves studied botany or zoology, though at a later age than the children we are talking about. Unfortunately, most textbooks on botany or zoology are really unsuitable for teaching young people. Some of them may have great scientific merit (though this is usually not the case), but as teaching material for the age that concerns us here, they are useless. Everything that we bring to our students in plant or animal study must be woven into an artistic whole. We must try to highlight the harmonious configuration of the plant’s being. We must describe the harmonious relationships between one plant species and another. Whatever children can appreciate through a rhythmic, harmonious, and feeling approach must be of far greater significance for Waldorf teachers than what the ordinary textbooks can offer. The usual method of classifying plants is especially objectionable. Perhaps the least offensive of all the various systems is that of Linné. He looked only at the blossom of a plant, where the plant ceases to be merely plant and reaches with its forces into the whole cosmos. But these plant systems are unacceptable for use at school. We will see later what needs to be done in this respect.

It is really pitiful to see teachers enter the classroom, textbook in hand, and teach these younger classes what they themselves learned in botany or zoology. They become mere caricatures of a real teacher when they walk up and down in front of the students, reading from a totally unsuitable textbook in an attempt to remember what they were taught long ago. It is absolutely essential that we learn to talk about plants and animals in a living and artistic way. This is the only way our material will be attuned to the children’s inner musical needs. Always bear in mind that our teaching must spring from an artistic element; lessons must not merely be thought out. Even when it is correct, an abstract kind of observation is not good enough. Only what is imbued with a living element of sensitive and artistic experience provides children with the soul nourishment they need.

When children enter class one, we are expected to teach them writing as soon as possible, and we might be tempted to introduce the letters of the alphabet as they are used today. But children at this age—right at the onset of the change of teeth—do not have the slightest inner connection with the forms of these letters. What was it like when we still had such a direct human relationship to written letters? We need only look at what happened in early civilizations. In those ancient times, primitive people engraved images on tablets or painted pictures, which still had some resemblance to what they saw in nature. There was still a direct human link between outer objects and their written forms. As civilization progressed, these forms became increasingly abstract until, after going through numerous transformations, they finally emerged as today’s letters of the alphabet, which no longer bear any real human relationship to the person writing them.

In many ways, children show us how the people of earlier civilizations experienced the world; they need a direct connection with whatever we demand of their will. Therefore, when introducing writing, we must refrain from immediately teaching today’s abstract letters. Especially at this time of changing teeth, we must offer children a human and artistic bridge to whatever we teach. This implies that we have children connect what they have seen with their eyes and the results of their will activity on paper, which we call writing. Experiencing life actively through their own will is a primary need for children at this stage. We must give them an opportunity to express this innate artistic drive by, for example, allowing them to physically run in a curve on the floor (see image). Now, when we show them that they have made a curve with their legs on the floor, we lift their will activity into a partially conscious feeling. Next we ask them to draw this curve in the air, using their arms and hands. Now another form could be run on the floor, again to be written in the air.

Thus the form that was made by the entire body by running was then reproduced through the hand. This could be followed by the teacher asking the children to pronounce words beginning with the letter L. Gradually, under the teacher’s guidance, the children discover the link between the shape that was run and drawn and the sound of the letter L.

Once children experience their own inner movement, they are led to draw the letters themselves. This is one way to proceed, but there is also another possibility. After the change of teeth children are not only musicians inwardly, but, as an echo from earlier stages, they are also inner sculptors. Therefore, we can begin by talking to the children about a fish, gradually leading artistically to its outer form, which the children then draw. Then, appealing to their sense of sound, we direct their attention from the whole word fish to the initial sound “F,” thus relating the shape of the letter to its sound.

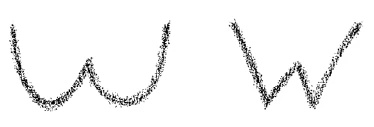

This method, to a certain extent, even follows the historical development of the letter F. However, there is no need to limit ourselves to historical examples, and it is certainly appropriate to use our imagination. What matters is not that children recapitulate the evolution of letters, but that they find their way into writing through the artistic activity of drawing pictures, which will finally lead to modern, abstract letter forms. For instance, one could remind the children of how water makes waves, drawing a picture like this first one, and gradually changing it into one like the second.

By repeating something like “washing waves of water—waving, washing water” while drawing the form, we connect the sound of the letter W with its written form. By beginning with the children’s own life experience, we go from the activity of drawing to the final letter forms.

Following our Waldorf method, children do not learn to write as quickly as they would in other schools. In the Waldorf school, we hold regular meetings for parents without their children present, and parents are invited to talk with the teachers about the effects of Waldorf education. In these meetings, some parents have expressed concern over the fact that their children, even at the age of eight, are still unable to write properly. We have to point out that our slower approach is really a blessing, because it allows children to integrate the art of writing with their whole being. We try to show parents that the children in our school learn to write at the appropriate age and in a far more humane way than if they had to absorb material that is essentially alien to their nature—alien because it represents the product of a long cultural evolution. We must help parents understand the importance of the children’s immediate and direct response to the introduction of writing. Naturally, we have to provide students with tools for learning, but we must do this by adapting our material to the child’s nature.

One aspect, so often left out today, concerns the relationship of a specific area to life as a whole. In our advanced stage of civilization, everything depends on specialization. Certainly, for a time this was necessary, but we have reached a stage where, for the sake of healthy human development, we must keep an open mind to spiritual investigation and what it can tell us about the human being. To believe that anthroposophists always rail against new technology is to seriously misunderstand this movement and its contribution to our knowledge of the human being. It is necessary to see the complexities of life from a holistic perspective. For example, I do not object at all to the use of typewriters. Typing is, of course, a far less human activity than writing by hand, but I do not remonstrate against it. Nevertheless, I find it is important to realize its implications, because everything we do in life has repercussions. So you must forgive me if, to illustrate my point, I say something about typewriting from the point of view of anthroposophic spiritual insight. Anyone unwilling to accept it is perfectly free to dismiss this aspect of life’s realities as foolish nonsense. But what I have to say does accord with the facts.

You see, if you are aware of spiritual processes, like those in ordinary life, using a typewriter creates a very definite impression. After I have been typing during the day (as you see, I am really not against it, and I’m pleased when I have time for it), it continues to affect me for quite a while afterward. In itself, this does not disturb me, but the effects are noticeable. When I finally reach a state of inner quiet, the activity of typing—seen in imaginative consciousness—is transformed into seeing myself. Facing oneself standing there, one is thus able to witness outwardly what is happening inwardly. All this must occur in full consciousness, which enables us to recognize that appearance, as form as an outer image, is simply a projection of what is or has been taking place, possibly much earlier, as inner organic activity. We can clearly see what is happening inside the human body once we have reached the stage of clairvoyant imagination. In objective seeing such as this, every stroke of a typewriter key becomes a flash of lightning. And during the state of imagination, what one sees as the human heart is constantly struck and pierced by those lightning flashes. As you know, typewriter keys are not arranged according to any spiritual principle, but according to frequency of their use, so that we can type more quickly. Consequently, when the fingers hit various keys, the flashes of lightning become completely chaotic. In other words, when seen with spiritual vision, a terrible thunderstorm rages when one is typing.

Such causes and effects are part of the pattern of life. There is no desire on our part to deride technical innovations, but we should be able to keep our eyes open to what they do to us, and we should find ways to compensate for any harmful effects. Such matters are especially important to teachers, because they have to relate education to ordinary life. What we do at school and with children is not the only thing that matters. The most important thing is that school and everything related to education must relate to life in the fullest sense. This implies that those who choose to be educators must be familiar with events in the larger world; they must know and recognize life in its widest context. What does this mean? It means simply that here we have an explanation of why so many people walk about with weak hearts; they are unable to balance the harmful effects of typing through the appropriate countermeasures. This is specially true of people who started typing when they were too young, when the heart is most susceptible to adverse effects. If typing continues to spread, we will soon see an increase in all sorts of heart complaints.

In Germany, the first railroad was built in 1835, from Fürth to Nuremberg. Before this, the Bavarian health authorities were asked whether, from a medical point of view, building such a railroad would be recommended. Before beginning major projects such as this, it was always the custom to seek expert advice. The Bavarian health authorities responded (this is documented) that expert medical opinion could not recommend building railroads, because passengers and railroad workers alike would suffer severe nervous strain by traveling on trains. However, they continued, if railroads were built despite their warning, all railroad lines should at least be closed off by high wooden walls to prevent brain concussions to farmers in nearby fields or others likely to be near moving trains.

These were the findings of medical experts employed by the Bavarian health authority. Today we can laugh about this and similar examples. Nevertheless, there are at least two sides to every problem, and from a certain point of view, one could even agree with some aspects of this report, which was made not so long ago—in fact not even a century ago. The fact is, people have become more nervous since the arrival of rail travel. And if we made the necessary investigation into the difference between people in our present age of the train and those who continued to traveled in the old and venerable but rather rough stagecoach, we would definitely be able to ascertain that the constitutions of these latter folks were different. Their nervous systems behaved quite differently. Although the the Bavarian health officials made fools of themselves, from a certain perspective they were not entirely wrong.

When new inventions affect modern life, we must take steps to balance any possible ill effects by finding appropriate countermeasures. We must try to compensate for any weakening of the human constitution through outer influences by strengthening ourselves from within. But, in this age of ever-increasing specialization, this is possible only through a new art of education based on true knowledge of the human being.

The only safe way of introducing writing to young children is the one just advocated, because at that age all learning must proceed from the realm of the will, and the inclination of children toward the world of rhythm and measure arises from the will. We must satisfy this inner urge of children by allowing them controlled will activities, not by appealing to their sense of observation and the ability to make mental images. Consequently, it would be inappropriate to teach reading before the children have been introduced to writing, for reading represents a transition from will activity to abstract observation. The first step is to introduce writing artistically and imaginatively and then to let children read what they have written. The last step, since modern life requires it, would be to help children read from printed texts. Teachers will be able to discern what needs to be done only by applying a deepened knowledge of the human being, based on the realities of life.

When children enter class one, they are certainly ready to learn how to calculate with simple numbers. And when we introduce arithmetic, here, too, we must carefully meet the inner needs of children. These needs spring from the same realm of rhythm and measure and from a sensitive apprehension of the harmony inherent in the world of number. However, if we begin with what I would call the “additive approach,” teaching children to count, again we fail to understand the nature of children. Of course, they must learn to count, but additive counting as such is not in harmony with the inner needs of children.

It is only because of our civilization that we gradually began to approach numbers through synthesis, by combining them. Today we have the concept of a unit, or oneness. Then we have a second unit, a third, and so on, and when we count, we mentally place one unit next to the other and add them up. But, by nature, children do not experience numbers this way; human evolution did not develop according to this principle. True, all counting began with a unit, the number one. But, originally, the second unit, number two, was not an outer repetition of the first unit but was felt to be contained within the first unit. Number one was the origin of number two, the two units of which were concealed within the original number. The same number one, when divided into three parts, gave number three, three units that were felt to be part of the one. Translated into contemporary terms, when reaching the concept of two, one did not leave the limits of number one but experienced an inner progression within number one. Twoness was inherent in oneness. Also three, four, and all other numbers were felt to be part of the all-comprising first unit, and all numbers were experienced as organic members arising from it.

Because of its musical, rhythmic nature, children experience the world of number in a similar way. Therefore, instead of beginning with addition in a rather pedantic way, it would be better to call on a child and offer some apples or any other suitable objects. Instead of offering, say, three apples, then four more, and finally another two, and asking the child to add them all together, we begin by offering a whole pile of apples, or whatever is convenient. This would begin the whole operation. Then one calls on two more children and says to the first, “Here you have a pile of apples. Give some to the other two children and keep some for yourself, but each of you must end up with the same number of apples.” In this way you help children comprehend the idea of sharing by three. We begin with the total amount and lead to the principle of division. Following this method, children will respond and comprehend this process naturally. According to our picture of the human being, and in order to attune ourselves to the children’s nature, we do not begin by adding but by dividing and subtracting. Then, retracing our steps and reversing the first two processes, we are led to multiplication and addition. Moving from the whole to the part, we follow the original experience of number, which was one of analyzing, or division, and not the contemporary method of synthesizing, or putting things together by adding.

These are just some examples to show how we can read in the development of children what and how one should teach during the various stages. Breathing and blood circulation are the physical bases of the life of feeling, just as the head is the basis for mental imagery, or thinking. With the change of teeth the life of feeling is liberated and, therefore, at this stage we can always reach children through the element of feeling, provided the teaching material is artistically attuned to the children’s nature.

To summarize, before the change of teeth, children are not yet aware of their separate identity and consequently cannot appreciate the characteristic nature of others, whose gestures, manners of speaking, and even sentiments they imitate in an imponderable way. Up to the seventh year, children cannot yet differentiate between themselves and another person. They experience others as directly connected with themselves, similar to the way they feel connected to their own arms and legs. They cannot yet distinguish between self and the surrounding world.

With the change of teeth new soul forces of feeling, linked to breathing and blood circulation, come into their own, with the result that children begin to distance themselves from others, whom they now experience as individuals. This creates in them a longing to follow the adult in every way, looking up to the adult with shy reverence. Their previous inclination was to imitate the more external features, but this changes after the second dentition. True to the nature of children, a strong feeling for authority begins to develop.

You would hardly expect sympathy for a general obedience to authority from one who, as a young person, published Intuitive Thinking As a Spiritual Path in the early 1890s. But this sense for authority in children between the change of teeth and puberty must be respected and nurtured, because it represents an inborn need at this age. Before one can use freedom appropriately in later life, one must have experienced shy reverence and a feeling for adult authority between the change of teeth and puberty. This is another example of how education must be seen within the context of social life in general.

If you look back a few decades and see how proud many people were of their “modern” educational ideas, some strange feelings will begin to stir. After Prussia’s victory over Austria in 1866, one often heard a certain remark in Austria, where I spent half my life. People expressed the opinion that the battle had been won by the Prussian schoolmaster. The education act was implemented earlier in Prussia than in Austria, which was always considered to have an inferior educational system, and it was the Prussian schoolmaster who was credited with having won the victory. However, after 1918 [and World War I], no one sang the praises of the Prussian schoolmaster.

This is an example to show how “modern” educational attitudes have been credited with the most extraordinary successes. Today we witness some of the results—our chaotic social life, which threatens to become more and more chaotic because, for so many, their strong sense of freedom is no longer controlled by the will and by morality, but by indulgence and license. There are many who have forgotten how to use real, inner freedom. Those who are able to observe life find definite connections between the general chaos of today and educational principles that, though highly satisfying to intellectual and naturalistic attitudes, do not lead to a full development of the human being. We must become aware of the polar effects in life. For example, people in later life become free in the right way only if, as a child, they went through the stage of looking up to and revering adults. It is healthy for children to believe that something is beautiful, true and good, or ugly, false, and evil, when a teacher says so.

With the change of teeth children enter a new relationship to the world. As the life of their own soul gradually emerges, which they now experience in its own right, they must first meet the world supported through an experience of authority. At this stage, educators represent the larger world, and children have to meet it through the eyes of their teachers. Therefore we would say that, from birth to the change of teeth, children have an instinctive tendency to imitate, and from the change of teeth to puberty, they need to experience the principle of authority. When we say “authority,” however, we mean children’s natural response to a teacher—never enforced authority. This is the kind of authority that, by intangible means, creates the right rapport between child and teacher.

Here we enter the realm of imponderables. I would like to show you, by way of an example, how they work. Imagine that we wish to give children a concept of the soul’s immortality, a task that is much more difficult than one might suppose. At the age we are speaking of, when children are so open to the artistic element in education, we cannot communicate such concepts through abstract reasoning or ideas, but must clothe them in pictures.

Now, imagine a teacher who feels drawn to the more intellectual and naturalistic side of life; how would this teacher proceed? Subconsciously she may say to herself, I am naturally more intelligent than a child who is, in fact, rather ignorant. Therefore I must invent a suitable picture that will give children an idea of the immortality of the human soul. The chrysalis from which the butterfly emerges offers a good metaphor. The butterfly is hidden in the chrysalis, just as the human soul is hidden in the body. The butterfly flies out of the chrysalis, and this gives us a visible picture of what happens at death, when the suprasensory soul leaves the body and flies into the spiritual world. This is the sort of idea that a skillful, though intellectually inclined, person might make up to pass on to children the concept of the soul’s immortality. With such an attitude of mind, however, children will not feel touched inwardly. They will accept this picture and quickly forget it.

But we can approach this task in a different way. It is inappropriate to feel, “I am intelligent, and this child is ignorant.” We have seen here how cosmic wisdom still works directly through children and that, from this point of view, it is children who are intelligent and the teacher who is, in reality, ignorant. I can keep this in mind and fully believe in my image of the emerging butterfly. A spiritual attitude toward the world teaches me to believe the truth of this picture. It tells me that this same process, which on a higher plane signifies the soul’s withdrawal from the body, is repeated on a lower level in a simple, sense-perceptible form when a butterfly emerges from the chrysalis. This picture is not my invention but was placed into the world by the forces of cosmic wisdom. Here, before my very eyes, I can watch a representation of what happens on a higher plane when the soul leaves the body at death.

If this picture leaves a deep impression on my soul, I will be convinced of its truth. If teachers have this experience, something begins to stir between their students and themselves, something we must attribute to the realm of imponderables. If teachers bring this picture to children with an inner warmth of belief, it will create a deep and lasting impression and become part of their being.

If you can see how the effects of natural authority lead to a kind of inner obedience, then in a similar light authority will be accepted as wholesome and positive. It will not be resented because of a mistaken notion of freedom. Teachers, as artists of education, must approach children as artists of life, because, after the change of teeth, children approach teachers as artists as well—as sculptors and musicians. In certain cases, the unconscious and inherent gifts of children are very highly developed, especially in children who later become virtuosi or geniuses. Such individuals never lose their artistic gifts. But inwardly, entirely subconsciously, every child is a great sculptor; they retain these gifts from before the change of teeth. After this, inner musical activities are interwoven with the inner formative activities. As educators, we must learn to cooperate in a living way with these artistic forces working through children. Proceeding along these lines, it becomes possible to prevent rampant growth in young people, and we enable them to develop their potential in the broadest possible sense.