Faculty Meetings with Rudolf Steiner

GA 300c

Sixty-Fifth Meeting

29 April 1924, Stuttgart

Dr. Steiner: The classes are overfilled in the first, fifth, sixth, and seventh grades. In the eighth grade and above, there are still some openings. We are limited by law in grades one through four; however, we will petition to be allowed to increase the number of students. We have had a number of new enrollments due to the conference. There are enough rooms.

They make a list of class teachers for the coming school year.

Dr. Steiner: You should telegraph Dr. Erich Gabert in Wilhelmshaven that he is to take over the 5c class, but he should first visit us for three weeks. The children should remain in the 5a and 5b classes until, but we will have to put sixty in each class. We will need to do that until he has settled in.

By Thursday we should hire Miss Verena Gildemeister to teach Latin and Greek.

The next question is what we do in the upper grades, nine through twelve. We can divide the ninth grade.

They divide the main lesson blocks for the upper grades among the teachers. They also assign teachers for foreign languages, religion, and eurythmy.

Dr. Steiner: Now we have the question of what to do about the final examinations for this coming year. Do we want to continue as in the past or keep the twelve grades pure and then add a thirteenth year? In that event, the question will not arise this year. For now, we need to know what the students want. A large number want to take the final examination.

The students from the first grade will come tomorrow at 9:00, and the opening ceremony will be at 10:00. I will meet with the students of the present twelfth grade at 12:00 in one of the classrooms. I will find out to what extent they want to take the final examination. The teachers should also attend the meeting. If the students expect to take their final examinations this year, we will have to swallow the bitter pill. That would ruin the twelfth grade. If possible, we should try to avoid the final examination this year and create a cramming class for next year.

A teacher asks about the physics curriculum for the twelfth grade.

Dr. Steiner: We need to develop the twelfth-grade curriculum. We still need to discuss that.

We teach the following in physics: In the ninth grade, the telephone and steam engine; the theory of heat and acoustics. In the tenth grade, mechanics as such. In the eleventh grade, modern electrical theory. So now in the twelfth grade, we should teach optics.

Use pictures instead of rays. We need to emphasize the qualitative. Light fields and light-filled spaces. Do not talk about refraction, but about how a light field is compressed. We need to remove discussions about rays. When you discuss a lens, you should not show a cross section of a lens and this fantastic cross section of rays. Instead, you need to present a lens as something that draws a picture together and compresses or expands it. Thus, you should remain with what can be directly shown through vision. Leave rays out entirely. That is what you should do in optics. Other things need to be considered in other areas, but what is important is to remain within the qualitative. I do not mean the theory of color, but simply the objective facts. Don’t go into some thought-up picture, remain with the facts.

Concerning optics in the broadest sense, it is important to present:

1. Light as such, that is the first thing. Then the expansion of light and how the intensity decreases in relation to the expansion, that is, photometry.

2. Light and matter, what is often called refraction. Enlargement and reduction of pictures and distortions.

3. How colors are created.

4. Polarization.

5. Double refractions, as they are called. That is, things associated with incoherence and the way light expands.

In the first section on how light expands, you should include mirrors and reflections.

Optics is very important because so much of it is connected with spiritual life. You can certainly see why there is so little understanding of the spiritual. That understanding could exist. There is so little understanding of the spiritual because there is no real epistemology. Instead, there are only abstract, crazy ideas. But why is there no genuine cognitive theory? It is because since Berkeley wrote his book about vision, no one has properly made the connection between seeing and knowing.

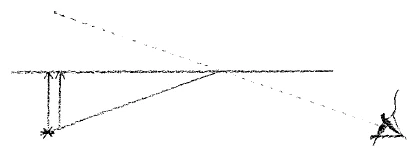

If you were to seek the connections, you would not explain what occurs in a mirror reflection by saying, “Here is a mirror and a light ray falls upon it perpendicularly.” Instead, you would say, “Here is the eye,” and then you would explain that when the eye looks in a straight line, nothing happens other than that it looks in a straight line. You need to present a picture that shows that a mirror basically “draws” a picture of the object for the eye.

You therefore have a subjective attraction. You need to begin with vision, and then all optics will present itself to you differently. If you look straight at something, then your view is in balance. However, if you look at something in the mirror, your view is no longer balanced, but one-sided in the direction of the object. The minute you have a mirror, your vision is polarized. One aspect of the spatial dimension disappears when you look into a mirror. I discussed this to an extent in my lectures on optics.

A teacher asks about history for the twelfth grade.

Dr. Steiner: Well, you have already gone through everything, so now the twelfth grade needs to gain an overview of the connections within history. As you know, I discuss in my pedagogy that at about age twelve, children should begin to understand causal concepts. Instruction in causal relationships would then continue until the twelfth grade, but you must enliven it and make it personal. In the twelfth grade, it is important to go a little below the surface, to try to explain some of the inner workings of history.

By presenting the entire picture of history in outline, you can show, for example, how the Middle Ages and more recent history are contained within ancient Greece, in a certain way. Thus, the Homeric period contains aspects of the time of the major tragedies of the Middle Ages, and the time of Plato and Aristotle relates to more recent times. The same is true for the Age of Rome. Thus, you should use individual peoples and cultures to treat history such that you show how things come together. You can show that ancient periods contained a Middle Ages and a more recent period. Therefore, show an ancient period, a middle period, and a recent period in each culture. The beginning of the Middle Ages is just as much an ancient period as the one in Greek history beginning with the ancient Greek myths.

Then you could also bring in broken cultures or incomplete cultures, like that of America which has no beginning, or the Chinese, which has no end, which ends in petrifaction, but is actually only the ancient period. Present the life of a cultural group in that way. Spengler was a little aware of this. Begin from the perspective that it is not just a sketch of historical events, but that different interwoven pieces have a beginning, middle, and end.

A teacher asks about twelfth-grade art class.

Dr. Steiner: The most proper thing to do would be to take Hegel’s aesthetic structure, symbolic art, classical art, romantic art. Symbolic art is the first, the art of revelation. Classical art goes more into external forms, and romantic art deepens that further. This can be seen in the art of various peoples. We find symbolic art with the Egyptians. We find all three in Greece, though symbolic and romantic art come up short. In more recent times, we find more classical and romantic art, and symbolic art comes up short.

Hegel’s Aesthetics is interesting even in the details. It is really a classic on aesthetics. That would be something for the twelfth grade. Symbolic art is typified in Egyptian art, where the other two were very rudimentary. Classical art is developed in Greece, where the forms that came before and after come up short. More modern art is classical and romantic, as Hegel describes. The most modern is actually romantic.

We begin instruction in the arts in the ninth grade, don’t we?

A teacher reports on how they have taught art in the past. In the ninth grade, specific areas of painting and sculpting; in the tenth grade, some things about German classical poetry; in the eleventh grade, how the poetic and musical elements are interwoven. One theme was to see how poetry and music since Goethe’s time move together under the surface.

Dr. Steiner: Work toward what I said for the twelfth grade; otherwise, what you have done until now is quite good. You should introduce them to the basics of architecture. If someone is teaching about architecture and construction in the twelfth grade, you could continue that discussion into architectural styles. We begin technology class in the tenth grade. We have weaving in the tenth grade, and you should show them how to make simple woven cloth. A sample is sufficient for that. In the eleventh grade, we have the steam turbine. They should have two hours a week in the tenth grade and one hour in the eleventh and twelfth grades.

A teacher asks about the ascidians as one of the twelve categories of animals.

Dr. Steiner: Those are the tunicates and salpas. Until now people have not seen them as being a separate genus.

A teacher asks about a student, B.K.

Dr. Steiner: I do not think it is really so terrible if such a boy is simply there. That will not pass by without a trace. The subconscious hears it. You will have to wait until he is fourteen. He should be unburdened as far as possible, so give him only a little bit to learn, but that should have a strong effect. His mother lies terribly. He should be required to paint at home.

A teacher asks about P.Z. in the sixth grade.

Dr. Steiner: Pay no attention to him. Let him play his tricks until he becomes tired of them. You should also see that the others pay no attention to him, so that he does his things alone.

A teacher: How should we seat the children in language class?

Dr. Steiner: In foreign languages, you could arrange the seating so that those who are interested in the sound sit together, and those who are interested in the content of the language sit together. In that way you would have groups of children you can treat differently and balance against one another.