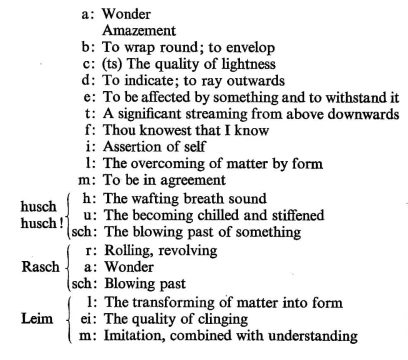

Eurythmy as Visible Speech

GA 279

II. The Character of the Individual Sounds

25 June 1924, Dornach

Yesterday I attempted to portray the general character of speech as such and the character of this visible speech of eurhythmy in particular. To-day I should like to describe the characteristics of the individual sounds, for only when the character and inner nature of these sounds reveal themselves to us shall we be able to understand the elements of eurhythmy. To begin with I should like to draw attention to the fact that in the life of humanity, in the course of human evolution, there has always been a more or less definite consciousness of these things. It is only in our time that, as I said yesterday, we have become so shrivelled up with regard to our attitude towards speech. There has always existed a certain consciousness of all that lies in the progression of sounds as they occur in language, an understanding of the fact that in the consonants there lies an imitation of outer forms and that an inward experience is contained in the vowel sounds.

This consciousness has been carried over more or less into the forms of the letters, so that in the formation of the letters in ancient languages,—in the Hebrew language, for example, particularly in the case of the consonants,—we may still see a sort of imitation of what takes place in the air, of what forms itself in the air when we speak. To a great extent this has been lost in all the more modern languages. (Among these I naturally include all those which, let us say, begin with the Latin language; the Greek language still retains something of what I mean.) Many things, however, still recall the time when an attempt was made to imitate in the forming of the letters that which actually lies in the formation, in the structure of the word; when a word was fashioned out of the consonantal element,—that is to say, the imitation of the external,—and out of the inner experience which had its source in the life of the soul. To-day it is only in certain interjections that we can still see dearly an instance of such imitation. Let us take an example which may serve to lead us more deeply into the real nature of eurhythmy.

When we pronounce the sound h,—clearly, not merely as a breath,—we have a sound which really lies midway between the consonants and the vowels. This is always the case with sounds which have a special relation to breathing. Breathing was always felt to be something in which the human being lives partly in an inner experience and partly in an out-going experience. Now the h-sound, this simple breath sound, may be felt,—and was indeed felt by primitive man,—as the imitation, the forming in the air of a wafting process, as the imitation of the way in which the breath is wafted into the surrounding atmosphere. Everything which is experienced as a wafting process is expressed through some word in which the h-sound is present, because the h itself is felt as the wafting process.

The vowel sound u can be felt as something which inwardly chills the soul, so that it takes on a certain rigidity and numbness. That is the inward experience lying behind u. U is the expression of something which chills, stiffens, benumbs; it is the sound which gives one the feeling of coldness. U, then, is the chilling, stiffening process.

And the sch,—that is the blowing away of something. It is the sound in which one feels that something is blowing past.

Now it is a fact that in certain districts, when an icy wind is blowing and one is numbed and stiff with the cold, people make use of the expression: husch-husch, husch-husch. In this interjection we still have an absolute experience of the h-u-sch: husch-husch. In primeval language all words were really interjections, ejaculations.

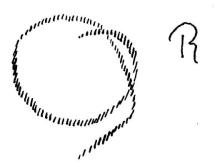

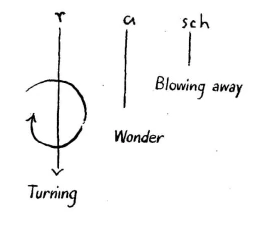

Let us take another combination of sounds. You all know the sound r. If one experiences the r-sound in the right way, one feels it as a turning wheel: r-r-r-r. Thus the r expresses a rolling, a revolving; it is the imitation of anything which gives the impression of turning, rolling, revolving. We must think of it, picture it, like this:

Yesterday I spoke already of the sound a. I told you that a expresses wonder. The sch-sound has already been described; it is the blowing past of something. And now we are able to feel the word ‘rasch’ (swift). It is easy to picture it. When anything rushes past it creates a certain wonder and disappears, is blown away: rasch.

So you see there is good reason for regarding the consonants as being an imitation. Here we have in the r the revolving, rolling, turning of something; in the vowel sound a the inner feeling of wonder: in the sch-sound something which goes away, which passes by.

From these examples you can already see that there is a certain justification for speaking of a primeval language, for you can feel that if human beings really experienced the sounds absolutely truly they would all speak in the same way; they would quite naturally, out of their own organization, describe things exactly in the same way.

It is a fact, as Spiritual Science teaches us, that there was once upon the earth a primeval language. You all know myths and legends dealing with this, - but it is much more than a myth or a legend. There is really something which lies at the back of all languages, and which is, in the way I have described, the primeval language from which all other languages have been built up.

When one turns one’s attention to certain facts of life and sees how, out of an infinite wisdom, they have been given similar names, then one is quite overwhelmed with the wisdom which reigns in the whole evolution of man, indeed in the whole evolution of the world. Consider the following, my dear friends,—and what I am now going to bring forward is no mere triviality, but it proceeds from out of a true and fundamental perception of the nature of man.

For people who think deeply over the problems which present themselves to the understanding, certain things that bear somewhat intimate relationship to life itself become riddles,—riddles which are simply passed over by the more blunted sensibilities of the average man. The fact that there is a similarity between the words ‘mother-milk’ and ‘mother-tongue’ may well be looked upon as a riddle of this kind. It is clear that one would not say ‘father-milk’, but the reason for not saying ‘father-tongue’ is less apparent. Where are we to seek for this parallel between ‘mother-milk’ and ‘mother-tongue’?

There are always inner reasons for such things. It is true that the external reason may frequently prove deceptive, but for these intimate facts of human evolution inner reasons are always to be discovered. When the child comes into the world the mother’s milk is the best nourishment for the physical body. Such things do not properly belong to lectures on eurhythmy, but if we had the necessary time, and if we were to analyse the mother’s milk in the right way,—not with the dead methods of chemistry but with a living chemistry,—we should find out why it is that the mother’s milk is the best nourishment for the physical body of man during the first stages of life.—Indeed, speaking from the medical-scientific point of view, one may go so far as to say that the milk of the mother is the best means of building up, of actually giving form to the physical body. This is the first thing we have to realize. It is the mother’s milk which gives form to the physical body. And it is the ‘mother-tongue’,—we said yesterday that the mother-tongue corresponds to the etheric body,—it is the mother-tongue which develops and gives form to the etheric body. For this reason we have a similarity between the words. First there appears the physical body with its need for the mother’s milk and then the etheric body with its need for the mother-tongue.

A deep wisdom lies hidden in such things. We find the deepest wisdom, not only in these word formations which can be traced back to ancient times, but also in many proverbial sayings and ideas. We should not look upon the wisdom concealed in old sayings and proverbs merely as superstition, but should recognize that very often wonderful and significant traditions are contained within them.

Having said this, having made my meaning clear to you, let us now proceed to a description of the nature of the sounds. When we understand what the sounds represent, how the vowels are the expression of inward experiences and the consonants the imitation of the external world,—when we understand how this is the case in every, single instance,—then we are led to a threefold study of eurhythmy,—artistic, educational and curative. I shall make use of everything which could possibly serve to give you a vivid picture of the individual sounds as they really are, so that tomorrow you will be able fully to understand the plastic gestures which we make use of in eurhythmy.

In a there lies a feeling of wonder, astonishment. In b, as I told you yesterday, we have the imitation of something which protects and shelters us from what is outside ourselves. In b we feel that we are enveloped in something. This can even be seen in the way that the letter is formed, only in modern writing the sheath is, as it were, doubled: B. B is always an enveloping, a kind of shelter. To put it somewhat crudely b might be said to be the house in which one lives. B is a house.

In my characterization of the various sounds in speech-eurhythmy I shall take the German language as my starting point. I could just as easily take the sounds of more ancient languages, but we will make a beginning with the German sounds and see how these reveal themselves to us in their true nature.[1]

Coming now to the sound c (ts),—I shall naturally not go into the formation of the written letters as these have mostly become degenerate and in any case, eurhythmists do not need to interest themselves so much in language from this point of view,—coming now to the sound c you will feel it to be some-thing which is in movement. It would be impossible to feel that with the sound c one would try to imitate anything which is in a state of rest. There is a certain force in the sound c; nevertheless, when you really experience what lies behind it, you will realize how impossible it would be to picture anything heavy in connection with it. It would never occur to you that with c you would wish to imitate something which would make you get into a great heat if you tried to lift it. On the contrary, the feeling that one has is that here is the imitation of something which is the reverse of heavy, which is really very light. It is the quality of lightness that is really imitated in the sound c. Thus one can say quite simply: In c we have the imitation of lightness.

If you enter into the intimate nature of the different sounds, you will, in the case of c, have much the same feeling as if in a circus you saw weights,—apparently made of iron and marked so and so many hundredweight,—lifted up quickly and easily by the clown. Imagine that you were to approach such a weight, in the belief that it were made of iron and immensely heavy, and that you were to lift it up. You would approach it, and in suddenly raising it, you would produce a movement very similar to the sound c. We have the same thing in Nature; for sneezing is not at all unlike a c. Sneezing is a lightening process.

It was said by the old occultists that the sound c in primeval language was the Regent of Health. And in Austria, when a person sneezes, we still have a saying: Zur Gesundheit (Your very good health). These are feelings which must be taken into consideration when studying the sounds, otherwise we shall not be able to come to any understanding of them in their reality.

D,—how should we most naturally express d? d. d. d. If someone were to ask you where a thing was, and you knew, the movement you would make to show him would very nearly approach the eurhythmic movement for the sound d. And if you wished to indicate that you expected your questioner to be astonished at getting such a speedy answer, then you would say: da (there). If you leave out the astonishment, the wonder, then there remains just the d. In such a case you are not so conceited us to wish to call up in your questioner the feeling of wonder; you simply show him where the thing is. In expressing d in eurhythmy one makes what may be called an indicating movement raying out in all directions. It is not difficult to feel this. So that we may say: D is the pointing towards something, the raying out towards something. The imitation of this pointing, of this raying out, of this drawing attention to something, all this lies in the sound d.

E is a sound which has always been of very special interest. As you already know e is the sound which gives expression to the feeling that something has been done to us and that we have to stand up against it. E: me will not allow what has been done to trouble us.

Here it may be well to introduce the sound t, Tao, and to explain its significance. You are perhaps already aware that a deep reverence rises up in those who begin to understand what lies in this sound. This Tao, t, is really the sound which has to be felt as representing something of the greatest importance. We may even go so fir as to say that it contains within it creative forces, forces which also have a radiating, indicating quality, but with t it is more especially a radiance which streams from heaven down on to the earth. There is a weightiness about the sound, and at the same time also a radiance. Thus we can say: T is the streaming of forces from above downwards.

Now it is, of course, possible for something which under certain conditions has to be felt as having great and majestic qualities also to make its appearance in ordinary everyday life. Let us take three sounds. Let us first take e as we have learned to know it. E expresses the feeling: Something has been done to me, but I stand up against it and assert myself. T, Tao: Something has burst in upon me. Let us try to show what is contained in this experience: Something has been done to me but I stand up against it—e. An event has taken place; it has suddenly burst in upon me—t: but it is soon over, it passes over; the blowing away of something—st. In this way we get the following combination of sounds: etsch. When do we make use of this expression? We use it when, for instance, somebody makes an important statement, which is, however, false, and we immediately jump to the conclusion that it is false. Now when we are in a position immediately to get rid of what has affected us, when this statement or whatever it is has burst in upon us like a flash of lightning but we destroy it and blow it away, then we say: etsch. Here you have an explanation of this combination of sounds. One feels the e particularly strongly, the being affected by something. One could not imagine saying itsch or atsch in such a case. But in an experience of this kind, when one has been affected by something but has been able immediately to get rid of it, then one obviously must use the expression: etsch.

Now out of the way in which you form the movement for e, out of your knowledge of eurhythmy, you will be able fully to enter into the gesture that in many districts accompanies this expression. This gesture is really very similar to the eurhythmic movement for e. Etsch, etsch (showing the corresponding movement). Here we actually have the eurhythmic movement for e. Such movements are absolutely natural and instinctive.

Thus behind the sound e there lies the experience of being affected by something and of withstanding it. Naturally when one describes such things the description tends to be awkward and inadequate. Everything depends on being able to feel what is meant.

F is a sound which is somewhat difficult to experience in an age which has such a lifeless, dried-up conception of language. But it may perhaps be of assistance to us, my dear friends, if I remind you of a phrase which you will know and which is in fairly general use. People say, when somebody knows a thing upside down and inside out: Er kennt die Sache aus dern ff. (He knows it out of the ff.) An extraordinarily interesting experience lies behind this phrase. When one finds the man in the street making use of such an expression and compares it: with what was said in the old Mysteries the result is truly remarkable. (You remember I said that I should make use of everything which could help us to gain a true understanding of the sounds, whether my examples were drawn from a cultured or from a more primitive source,—the latter being the more fruitful, naturally.) In the ancient Mysteries there was still a living understanding of the words: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God’; there was still a living feeling for the creative power of the Word, of the Logos. (Logos is not to be translated ‘wisdom’; indeed, by doing so many modern scholars have betrayed their lack of understanding for these things. Logos must unquestionably be translated ‘Verbum’, ‘Word’,—only the word ‘Word’ must be understood in the right way, in the way in which I explained it yesterday.)

Now, in the old Mysteries of Western Asia, Southern Asia and Africa it was said, when speaking about the sound f: When man utters the sound f he expels out of himself the whole stream of his breath. It was by means of the breath that the Gods created humanity, and the whole of human wisdom is contained m the air, in the breath. So that all the Indian was able to learn when through Yoga Philosophy he learned to control his breathing and as a result was able to fill himself with inner wisdom,—all this he felt when he uttered the sound f. In the old Indian Yoga practices the pupil had the following experience: he practised Yoga exercises, the technique of which consisted in this, that he became inwardly aware of the organization of man, inwardly aware of the fullness of wisdom. In uttering the sound f he became conscious of the wisdom contained in the Word. F can therefore only be rightly understood when one tries even to-day to understand a certain formula, which is very little known in the world, but which nevertheless did once exist and in the old I? Egyptian Mysteries ran somewhat as follows: If thou wouldst proclaim the nature of Isis, of Isis who contains within herself the knowledge of the past, present and future and from whom the veil can never entirely be lifted, then thou must do this in the sound f.—

The making use of the process of breathing in order to fill oneself with the being of Isis, the experiencing of Isis in the out-going breath-stream,—this it is that lies in the sound f. So that f—not indeed exactly, but at any rate to some extent—can be felt as the expression of: I know.—But more lies in it than this. ‘I know’ is really only a feeble expression of what we should feel in the sound f. For this very reason the feeling for f was soonest lost. F may be felt somewhat as follows: Know thou, to whom I speak, when I say f to thee I would make thee aware that I can teach thee. Thou must know that I myself have knowledge.—

It would therefore seem natural to you, absolutely natural, if, someone desirous of putting another right were suddenly to approach him giving vent to a sound similar to f. There are many interesting words, words which would well repay study, in which the sound f occurs in some connection or other. This study, however, you can carry out for yourselves; and you will continually be reminded of all that I have told you about the inner nature of the sound f.

I have already spoken about the sound h; we know that it is the blowing, the wafting past of something.

And now i. It is easy to feel i as an assertion of oneself, as positive self-assertion. In the German language there is a very happy example of this. It is our word for the expression of the; affirmation or the assertion of something: Ja (yes). Here certainly there is the indication of a consonantal element, but the i is nevertheless present and is followed by wonder, by amazement. Assent, affirmation, cannot be better expressed than by an assertion coloured by wonder. We said yesterday that the quality of wonder really represented man in his true being; and when we add to this the assertion of oneself: Ja, then we could not have a dearer, more definite expression of the affirmative. Thus in i we have the assertion of self. We shall see how important it is for eurhythmists to understand that behind the sound i there is always a vindication of oneself, an assertion of oneself.

L is a very remarkable sound,—as I am pronouncing it now it contains a hint of e,—but I mean the pure sound l. Try to realize what you really do when you pronounce l. Try to, realize especially what you do with your tongue. You use your tongue in a very skilful way when you pronounce the sound l, l, l, l. You become aware of a creative, form-giving element when saying this sound. Indeed, if one were not too, terribly hungry, one might almost satisfy one’s hunger by, simply saying the sound l very distinctly and over and over again. We feel l to be something absolutely real, as real, for, example, as if we were to eat a dumpling—a specially nice, soft dumpling—and were to allow it to melt on the tongue with a feeling of great satisfaction. We can have a like experience, when we pronounce the sound l, l, l, very distinctly. There is: something creative, something form-giving in this sound. And the sculptor is very much tempted when working on the figures which he is creating to make a movement of the tongue similar to the movement which the tongue makes when forming the sound l. Though of course the sculptor does not say l aloud; he only makes a similar movement with his tongue. And anyone able to feel the shape of a nose, for instance, with his tongue,—where the feeling for form, the feeling of l is so strong,—such a one would undoubtedly be very successful in modelling noses! It was said in the old Mysteries that l is the creative, form-giving element in all things and beings,—the force which overcomes matter in the creation of form.

You will easily feel that the diphthong ei (German ri, English i (as in sight)) corresponds to an affectionate caress. When dealing with a child one often makes use of this sound. Ei, ei—an affectionate caress.

I shall next have to describe the sound m, and we shall see that m has the quality of entering right into something, of taking on the form of something outside itself. Let us now suppose, my dear friends,—and here again I am not merely trifling but what I have to say is drawn from out of the history of the ages,—let us suppose that we had some sort of substance and determined that this substance should be the means of transforming matter, of giving form to matter. Let us put the story together. In the first place we demand of this substance that it shall transform matters and give it form and shape. That la to be its main attribute. It is to give form to matter, but in such a way that it clings closely and lovingly to something other than itself, in much the same way as when one caresses a little child: ei, ei,—this is the expression of a caressing quality. The substance must cling to something. And this clinging quality must be retained; the substance must as it were take on a form which is foreign to it, so that it appears exactly the same as this external form; it imitates this form quite exactly. And now let us suppose that we express this transformation of matter into form by means of a combination of sounds. We say l. The clinging quality, ei. The taking on of some external form: m. Thus we have a word: Leim (putty) which is quite specially characteristic of the German language, quite apart from any other consideration. It is upon such combinations of sound behind which there lies hidden the active, evolving genius of language, that the life of this genius of language really depends. It occurs from time to time that when in some language or other a word already exists, although perhaps in a vague, indefinite form, that this word is metamorphosed and introduced again into a language of a later development. The original feeling: underlying the word, however, remains unchanged, and is retained by the people speaking the later language. An understanding of language is a much more complicated matter than is usually supposed. To-day people treat language in a really terrible fashion. In ordinary everyday life which rests upon superficiality and convention such a treatment of language is perhaps not out of place; but its effect upon the human soul is nothing short of devastating, how utterly devastating it is impossible to say. For instance, somebody wishes to translate a book or a poem. So he proceeds to hunt in the dictionary or to search his memory in order to discover the corresponding words. And having more or less transposed it in this way he calls it a translation. But it would really be more correct to call it a mistranslation,—for this is a wrong track altogether. Nothing is more appalling than this method of transferring something from one language into another.

Let us therefore study this question from the following point of view. Assuming that there was once a primeval language (alike of course for all men),—and there is no doubt that this language did exist,—assuming that there was once a primeval language, then the question naturally arises: How is it that the, many different languages came into being? How does it come about that if we take a German word, the word ‘Kopf’ (head) for instance, and translate this into Italian, we have to say ‘testa’? We have the German word ‘Kopf’ and the Italian word ‘testa’. When we begin to enter into the true nature of language we must ask ourselves the question: How is it that the Italian feels the sounds in ‘testa’ which are totally different from those felt by the German when he makes use of the word: ‘Kopf’? According to the rules of translation the two words should have the same significance. If the word ‘Kopf’ were really to be experienced, then the Italian, and even the Chinese would perforce have to say ‘Kopf’ also. How then can the origin of the different languages be explained?

What I am now going to say may make you double up with laughter, but it is nevertheless true. The German makes use of the word ‘Kopf’; the Italian would also make use of this word if he wished to designate the same thing. But he does not wish to do so. The German point of view lies outside his field of vision. What the German expresses in the word ‘Kopf’, that to which he gives the name ‘Kopf’ does not occur in the vocabulary of the Italian language. Were the Italian desirous of expressing the same thing, he, like the German would say: ‘Kopf’. What then does the German mean when he says: ‘Kopf’? He means to describe the form, the rounded form of the head. It is easy to feel this rounded form in the word ‘Kopf’. Later on when we have studied the sound k and all that we need in this connection, we shall be able to realize more dearly that it is the rounded form which is meant here. Now when the word ‘Kopf’ is shown in eurhythmy try to see how this rounding appears in the middle of the word. (Demonstration). The German describes as ‘Kopf’ the round form of the head as it rests on the shoulders.

Were the Italian to have the same experience, he also would say ‘Kopf’ not ‘testa’. What then does he experience? The Italian does not experience the rounded form, but he feels what is implied in a statement, in a testimony; he is more aware of what underlies the word ‘testament’. Thus the act of making a testimony, making a declaration, an affirmation, this it is which is felt by the Italian and for this reason he says: ‘testa’. He means something totally different from the German. The words ‘Kopf’ and ‘testa’ only appear to describe the same thing; in reality they are fundamentally different. In the one case, in the German word, the form of the head is described as it rests upon the shoulders. And in German, if one wishes to lay emphasis upon the roundness of the form one can make use of an expression which has in it at the same time a certain element of contempt and say: ‘Kohlkopf’. (Cabbage-head. Block-head.) You will agree with me that here there can be no shadow of doubt that the rounded form is meant.

But the head as it rests upon the shoulders is not felt as a round form by the Italian; he feels it to be something which makes an assertion, a declaration. For this reason he says: ‘testa’, and feels in this word all that I have described.

This lack of understanding is very general among translators. As a rule we translate without paying any attention to the fact that we should transpose ourselves into the whole atmosphere of the other language in order to catch its exact shades of meaning. Just think how external it is when one translates according to a dictionary. One misses just those things which are most essential and passes them by in sublime unconsciousness.

Let us now return to the sound m,—that sound which makes such a wonderful ending to the sacred Indian word Aum. M contains within it the element of comprehension, of understanding. In the way in which the sound is carried on the stream of the breath we feel that it conforms itself to everything and understands everything. M signifies that which is deeply felt and understood. I remember that my village schoolmaster said mhn when he wanted to show that I had answered a question rightly. At such times he always said mhn,—i.e., he understood; it, he agreed with it; the hn was only the expression of his satisfaction. M, therefore, may be said to be the expression of, agreement. It clings to something and is in agreement with it, as the m at the end of the word Leim.

It is clear from these few examples that in each sound there lies concealed a whole world of experience. And we can easily:, realize that if we were to express ourselves by means of sounds only, instead of using our ordinary words, we should indeed have a simpler and more primitive language, but it would be one which would combine with this simplicity a much deeper intimacy and understanding.

As eurhythmists it is very necessary that you should gradually feel your way into the real nature of the sounds; for eurhythmy does indeed consist of a plastic formation of movement and gesture. Such movements are, however, in no way arbitrary nor transient. On the contrary the movements of eurhythmy are cosmic in their nature, they are full of significance, they, could in no way be other than they are.

In the next lecture I shall describe to you the other sounds which I have not touched upon to-day, and then gradually we shall consider the main characteristics of the actual movements which we use in eurhythmy. We shall see how these movements express in their very essence exactly the same as is expressed by the sounds themselves as they are breathed into the air, as they take shape in the air.