Cosmosophy II

GA 208

Lecture VIII

5 November 1921, Dornach

We have been considering the human being in relation to the cosmos. To people who do not know anything beyond the present-day way of looking at things it must seem rather absurd to hear of a link being made between the essential nature of the human being and the essential nature of the cosmos, and I am certain that the majority of people will consider this to be quite unscientific. Yet when we think of the spiritual streams of today there is an urgent need to draw attention to exactly the kind of thing we have been considering and to do so quite energetically. For these things may fairly be said to be entirely in line with modern thinking. The problem is, modern thinkers are rejecting them with great vehemence, which is doing untold harm to the life of mind and spirit.

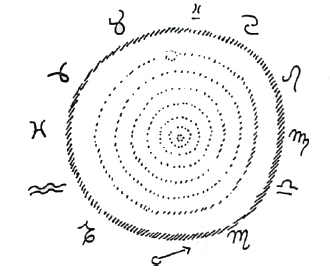

To begin with, we’ll sum up what I have been presenting in recent lectures. We have been considering the human form as the outcome of something the causes of which must be looked for among the fixed stars, and particularly the constellations of the zodiac as their representatives. We found that to understand the human form we must first of all look to the zodiac; its twelve constellations make it possible for us to understand the human form in every detail.

To understand the levels of human life we must look to the planetary system for the elements which will enable us to do so.

We then moved on from understanding the levels of life to understanding the soul principle. There we had to go to the human being himself, to the form he has been given and to that which lives in him. We also looked at the thinking, feeling and will aspects of the inner life in relation to the human form and the levels of life. Yesterday we attempted to look for the element of mind and spirit in the inner life. With the soul principle we move from the cosmic periphery to life on earth as such—that is, if we consider the soul principle during life between birth and death. We are able to approach it by considering its true relationship to the human form and to human life.

Yesterday we found that the spirit, which human beings only experience in images, has to be looked for in the sphere of the soul. If I may put it like this, we are coming down to earth from heaven. To consider the human form we have to go as far as the fixed stars; to consider human life, we need to go to the sphere of the planets; to consider the human soul in its relationships between birth and death, we must first of all descend to earth. Thus the human being becomes a whole for us in his relationship to the cosmos.

Now if we really appreciate all this, we shall be able on the basis of it to draw the borderline between animal and human nature. The way it may be done is as follows. If we consider the principle which can be understood in relation to the zodiac and how it is in humans and in animals, a difference emerges. But to see the whole of it we need to consider how the zodiac, the planetary sphere and the earth, with everything presented in yesterday’s lecture, act on human beings and on animals. Outside the human being the physical world does not take the form it does in the human body. We find it in the forms of the mineral world, a world very different from the human physical body. This is because in the human being the physical principle is clothed in an etheric and an astral principle and in I nature, all of which change the physical principle, adapting it to suit their needs. In the physical world outside the human being we see the physical principle as it presents itself when not imbued with etheric, astral and I nature.

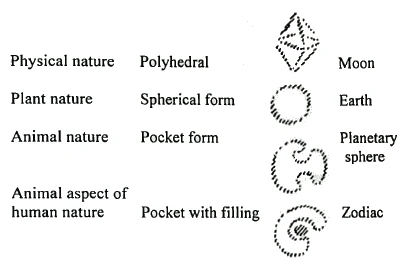

The inherent form principle of the mineral is the crystal, a polyhedral form.

To grasp this form we must first of all consider the physical matter which has developed out of the forces which are active in the mineral sphere. We have to visualize that in an elongated mineral specific forces act in this direction to elongate the mineral (see crystal on the right). The forces acting in this direction (horizontal line in the centre) are perhaps less powerful, or we may say they act to make the mineral more slender in this direction, and so on. In short, in order to talk about minerals at all, we have to visualize these forces being at specific angles to each other, acting in specific directions, irrespective of whether they come from inside or outside. And above all we have to visualize these forces as existing in the universe, at least to the point where they take effect in the sphere of the earth.

Being effective, they must also have an effect on the human physical body, which means it, too, must have the inherent tendency to become polyhedral. It does not actually become polyhedral because it still has its ether body and astral body which do not allow the human being to turn into a cube, octahedron, tetrahedron, icosahedron, and so on. The tendency is there, however, and it would be fair to say: In so far as human beings are physical beings, they tend towards becoming polyhedral. So if you are glad that you do not have to walk around as a cube, a tetrahedron or octahedron, the reason is that the powers of the astral and ether bodies act against the forces—octahedral, cubic, or whatever—inside you.

Now we are not only a physical body but also have an ether body. Through it we are in essence at one with the plant world. Through the physical body we represent the mineral, or physical, world around us, through the ether body the plant world around us.

Plants are also part of the physical world and therefore have the tendency to be polyhedral, but they add to it a tendency to be spherical. Circumstances may occasionally cause minerals to occur in spherical form, but this is not their true form. There has to be scree, or something of that kind, if a mineral is to be spherical.

In plants, every single cell seeks to achieve spherical form; in humans only the head goes a little in that direction. We owe this spherical form essentially to plant nature. The fact that not all plants are spherical is in the first place due to their having to fight against polyhedral form, which has its own outcome, and secondly to the plant form having also to fight against a cosmic, astral principle. You will remember from earlier lectures that a cosmic, astral principle presses down on the plant from above. All this modifies the spherical form. You also get spheres imposed on spheres. But the essential plant form is a sphere.

Seeking to achieve spherical form the plant assumes the form of the earth itself. As you know, the earth is a sphere in the cosmos, and so is every drop of water. Only the mineral parts of the earth are polyhedral. As a whole, the earth is spherical. The plant, or the life principle, therefore seeks to attain to the spherical form and in doing so is really trying to recreate the form of the earth.

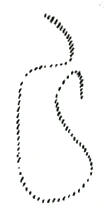

Let us now go higher and consider what the human being is because of the astral body. Here the human being is something representing the animal nature found in the animal world. In the physical, mineral nature of man we look for the polyhedral form, in human plant nature for the spherical form which reflects the planet earth (Fig. 28). Animal nature can be understood if we do not stop at the spherical form but add something to this form. We have to add pockets, or sacs, to the spherical form, like this:

It is in the nature of the animal form that a pocket element breaks up the sphere, with pocket-like inroads made everywhere. Consider your eye sockets—two pockets coming in from the outside. Consider your nostrils—two pockets. And finally consider the whole of your digestive tract from mouth to stomach. It is possible to arrive at this if you let a pocket develop, starting at the mouth, which goes all the way down.

You always get the pocket form added to the spherical form when the transition has to be made from plant to animal form.

We can come to understand the pocket form if we lift our eyes from the earth to the planetary system. You will find it easy to see that the earth seeks to give its own form to everything that lives on it. But a planet acting from outside counteracts the earth forces and makes pockets in the spherical form given by the earth. The different creatures of the animal kingdom are provided with such sacs, or pockets, in a wide variety of ways. Consider the planets and the different ways in which they act. Saturn makes a different kind of inroad than Jupiter or Mars. The lion is equipped with a different kind of inner sac-nature for the simple reason that the planetary influences on it are different from those on the camel, for instance. So in this case we have sacs being formed.

But in animals—and this means above all in higher animals, for the situation is different with the lower animals—and also in human beings something arises which does not merely come from the planetary realm, so that we are able to say: The essence of both animal and human nature is to have more than just the pocket form. This would be the case if there were only the planets and if the firmament of fixed stars had no influence. Something is added to the pocket form. In many situations people are satisfied when they have not just a pocket but something in it. And it is indeed the case that it is the essence of the animal aspect of human nature to have a pocket with something to fill it. So we have a spherical form with a pocket and the pocket is filled.

You only need to look at the sense organs, the eye. You have first of all a pocket, which is the eye socket, and then something to fill it. And this fulfilment,25Steiner is using a slightly unusual term here, which usually translated as “fulfilment”. For the translation I have largely used terms like “filling”, “that which fills them” or “which are filled”, but I felt the note should be sounded just once in this passage. which occurs particularly in the sense organs, relates to the zodiac just as the pocket form relates to the planetary sphere. Human beings have the most complete animal organization in this respect, which is also why they have twelve pockets with their fillings, though this is disguised in all kinds of ways. This is why I had to list twelve sense organs in my Anthroposophy.26Steiner R. Anthroposophy (A Fragment) (GA 45). Tr. C. E. Creeger. New York: Anthroposophic Press 1996.

We can now go back and ask: Which cosmic principle relates to the polyhedral quality? You see, if we consider the earth, it has the life form if seen as a whole, and if it consisted entirely of water it would only show this form. But all kinds of disruptions enter into the water. You can observe these disruptions in the tides, for instance. There the water is given configuration. Next, let us look back to earlier stages of configuration for the liquid earth, when it first began to develop solid elements. It is still possible to see today that the tides are connected with the moon, and everything polyhedral which becomes part of the configuration of the earth relates to the moon.

Thus we are able to say: The polyhedral or physical nature of human beings is connected with the moon, their vegetable or etheric nature with the earth, their astral nature, which would produce the pocket form, with the planetary sphere, and the filling of the pocket with the zodiac.

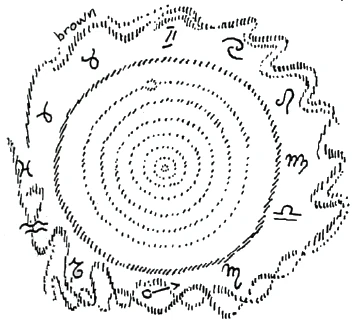

What I have written on the board applies in a different way to humans than it does to animals. You see, with animals it is truly the case that the heavens only have significance as far as the sphere of the zodiac, meaning everything which lies within it. Anything which lies outside it holds no significance for the animal. Ancient wisdom was therefore quite right in calling it the “zodiac”,27From the Greek “ho ton [long “o”] zodion [long “o”s] kyklos” = the circle of the sculptured figures of animals. for it was also able to say: Everything outside the zodiac in the universe might just as well not exist, for the animals on earth would still be exactly as they are. Only what lies below the zodiac, together with the earth and the moon, has significance for animals. What lies beyond the zodiac has, however, significance for human beings, for it influences the filling of the pockets.

For the animal we have to say: Everything which lies inside the zodiac influences the filling of the pockets. We therefore have to go into the zodiac itself and then we are able to explain how the filling of the pockets presents itself. With humans, we have to go beyond the zodiac (Fig. 34, brown) if we want to explain what goes on in the sphere of the senses, for example. In this respect, human beings go beyond the zodiac, animals do not.

It is also the case that in animals, the planetary sphere as such has a direct influence on the pockets. As the pockets continue inwards, to form the organs, animal organs are perfect reflections of the principles relating to the planetary sphere. Human beings again go a little further and we are able to say that in human beings, the region closer to the zodiac influences the pockets.

In animals, the earth has a direct effect on everything tending to assume spherical form. This is not possible in human beings, who otherwise would be animals, with a tendency to be spherical. In a sense, animals tend towards the spherical form. Here (Fig. 35) we have the backbone, then the legs. Animals are however prevented from becoming a complete sphere.

The back bone forms part of the sphere. Human beings tend to move away from the earth principle, just as they have moved away from the zodiac, and from the planetary sphere, towards the zodiac. We are able to say that the human spherical form is created by moving towards the planetary sphere. Human beings walk upright, however, and seek to go beyond mere adaptation to earthly principles.

With reference to the polyhedral element we have to say that the moon gives it directly to the animal. Human beings also seek to move out of the influences of the moon, “away from the moon”, as we might say, to receive their polyhedral element from a region between earth and moon. This means, however, that the moon still has an influence. In the fifth place, therefore, we must look to see what the moon, which in animals brings about the polyhedral element, is doing in human beings. It brings about a polyhedral element in humans, but as an image. Animals have the polyhedral element in their configuration; humans lift it out of the organism. Mathematical and geometrical ideas become image, taken out of the living physical body. Today, people primarily visualize and want to understand things in mathematical terms because they are able, under the moon’s influence, to lift their own polyhedral element out of the body, so that it enters into the conscious mind. We are thus able to say that thanks to the moon, we are able to understand the polyhedral element in images.

| Beyond the zodiac | Filling of pockets |

| Towards the zodiac | Pockets |

| Towards the planetary sphere | Spherical form |

| Away from the moon | Polyhedral |

| Moon | Understanding the polyhedral in images |

| Zodiac | Filling of pockets |

| Planetary sphere | Pockets |

| Earth | Spherical form |

| Moon | Polyhedral |

So you see how by considering the human being’s relationship to the cosmos we not only arrive at the outer form we have been considering in recent years but also understand how human beings gain inner form and structure. We see how they create their nasal cavities, or the stomach, as sacs or pockets. If we were to take this further we would understand the organs altogether and how they take internal form out of the whole cosmos. If we want to understand the human being we must always draw on the cosmos. We have to do so when we ask why we have an organ such as the lung, for instance. Essentially the lung can only be understood if we grasp that initially, in the embryo, a kind of sac forms, going inwards, with physical matter forming a lining. The sac-like form then tears itself free on the outside, and the organ closes itself off as an internal organ. We come to see why there is a lung, or any other organ, inside the human being if we perceive this organ to have originated from a sac, with the inner end of the sac thickening and due to other circumstances taking on a particular configuration. An organ such as the stomach can be seen as a sac extending inwards. An organ such as the lung, the heart or the kidney also starts as a sac, but it thickens here (Fig. 36), tears off here, and you have a closed-off internal organ.

Yet even with these closed-off organs—if we ask ourselves why they are in a particular place in the human organism, or why they have a particular shape or internal structure, we always have to consider the human being in relationship to the whole universe.

If a modern scientist were to hear of anthroposophists wanting to explain the lung, heart, liver, and so on out of the cosmos, he'd say we were quite mad. Members of the medical profession in particular would call this madness. They should not do so, however. It is up to them to realize that anthroposophy is actually trying to meet them half-way as they pursue their course clinging firmly to their accustomed blinkers. Let me give you a small example to prove this.

I have here before me a booklet written by the physician, medical scientist and biologist Moriz Benedikt in 1894.28Benedikt, Moriz (1835–1920), Hypnotismus und Suggestion, Leipzig & Wien 1894. I tend to quote this gentleman quite often, though I actually do not much like doing so, for apart from anything else, he shows himself to be terribly conceited, practically on every page he writes. He is also quite inflexible as a Kantian. There is, of course, the mitigating circumstance that he has made up his own Kantian ideas to suit himself, presenting them with some inflexibility. The man is extraordinarily gifted, however. He is not interested in anthroposophical ideas or anything of the kind, but it is fair to say that simply by being involved in medicine and science he has arrived at a reasonably unbiased view as to the value of his scientific outlook. He cannot get out of it; yet in a strange way he peers out. The others are also caught up in their science as if in a prison, but they do not even look at anything outside. He keeps looking at the outside world, and this allows him to arrive at extraordinarily interesting conclusions. His vanity has made him a great many enemies, and he will therefore sometimes say things about enemies who show themselves with their masks off—generally these people are “friends”, maintaining closed ranks. His colleagues have tended to put him down, and he therefore says things about them that are highly typical. He knows nothing about anthroposophy, of course, but still, if we consider anthroposophy in terms of its qualities it would be fair to say that, qualitatively speaking, he is an anti-anthroposophist. However, in the booklet I have before me he says:

The self-righteous ignore or deny anything that does not fit in with their point of view, persecuting not only the teaching, but even more bitterly the teachers. Self-righteousness is a peculiar kettle of fish. It smells sweet to the self-righteous but gives off a sharp, biting odour for others. Self-righteousness is by its very nature closely bound up with the scholars’ trade, so much so that although I hate the self-righteous I often ask myself: How often and in how many instances have you yourself been self-righteous? I’d be most grateful to anyone who would give me an exact answer to the question.

For my part, I am convinced that far from being grateful he would complain like anything if we were to make him aware of his own self-righteousness. Yet in his own peculiar way he has a particularly good eye for self-righteousness in others.

He goes on to speak of his own history, wanting to show that he has become a different kind of medical man from his colleagues. He writes:

Two severe strokes of destiny spelled disaster for my own development and also for the scientific position relative to the subject under discussion.

You’ll immediately be aware of a nice touch of vanity in what follows:

In the first place, I studied mathematics and mechanics before joining the medical profession. In those days we had an eminent mathematician at Vienna University, Professor von Ettingshausen,29Ettingshausen, Andreas, Freiherr von (1796–1857), mathematician and physicist. who presented the most difficult problems in the mathematics of physics and caught our interest. I heard him develop the theories of Cauchy30Cauchy, August Louis (1789–1857), French mathematician. and Poisson.31Poisson, Siméon Denis (1781–1840), French mathematician and physicist. Petzval32Petzval, Joseph (1807–1891), Austrian mathematician and physicist. taught us to express the problems of mechanics in mathematical formulas. It will be easy to show, however, how disastrous mathematical thinking is for a member of the medical profession, and above all a clinician.

Well, we shall see why it is disastrous, especially if such a person knows something about medicine. Professor Benedikt goes on with his story. You would have thought it to be a good stroke of destiny to be a mathematician, but he calls it a bad one, because it taught him to think. Other clinicians were apparently unable to think, and they hated him for having studied mathematics, for it meant he knew more than they did.

The second stroke of destiny to come in the days of my youth was that I became a student of Skoda.33Skoda, Joseph (1805–1881), physician; together with Rokitansky established the high reputation of the Viennese School in its heyday. I am still attached to his teachings today. He was the Kant of medical philosophy, and his mind rose to sublime heights not in books but in the discussion of diagnoses, indications for treatment, and particularly in postmortem reviews. Skoda had been a mathematician when young

—clearly another stroke of destiny!—

and had brought the most important and fundamental scientific thinking to medicine, though unfortunately only in isolated instances; the important insight I received from Skoda, having already been firmly convinced of it through my mathematical studies, is that in establishing scientific proof, we must be aware not only of what we know but also of what we do not know.

Benedikt had thus also studied under Skoda. The idea was that when using modern scientific methods—for this was the subject under discussion—we should be aware not only of what we know but also of what we do not yet know. Benedikt really did represent this principle with some degree of fanaticism in numerous treatises. He goes on to say:

This basic rule of medicine is not known to the majority of biologists, and indeed is incomprehensible to them. Some years ago, for example, I sent a manuscript in a foreign language to an anatomist, asking him to correct the language. When it came to the above statement, he wrote in the margin that he did not understand the meaning of it.

Benedikt says here that we should also consider what we do not know, and he wanted the other individual to translate the statement into proper French. The anatomist had written, however, to say he did not understand it.

When I showed the comment written in the margin to a professor at the technical university he smiled. The statement is perfectly clear to anyone involved in the exact sciences.

The man smiled because he understood mathematical thinking; it amused him that members of the medical profession thought they could ignore the things they did not know. An engineer must know what he does not know, for he has studied mathematics.

When I told a famous medical expert in Vienna of the odd reaction from my medical colleague, he said rather naively: Well, how are we to know the unknown?—This historical anecdote casts a sharp light on the method of thinking still prevalent in modern medicine and on the colossal errors made day by day and hour by hour in the medical literature.

These are the words of a medical man! But we now come to a most important point. Moriz Benedikt tells us what happens in medical science, where no account is taken of the unknown:

The problems generally arise with reference to the biology of an organ, its function, for instance. The conditions on which the function is based are partly unknown and still have to be found.

He goes on to give an example:

The liver, for instance, secretes bile. The reason for this secretory process lies mainly in the specific biochemical properties of the cells.

Let us ignore the fact that he is referring to the biochemical properties of cells, which does not really make sense. We are taking the point of view he takes in speaking of the liver.

The reason must be found as to how these differentiated properties evolve;...

He wants to find the reason why the liver is different from other organs; he intends to consider the unknown. It is known that the liver secretes bile. But now we come to the unknown, and mark you well, he produces a considerable list:

The reason must be found as to how these differential properties evolve; how the organ develops from its elements; how it comes to be in its particular place; why it relates to surrounding organs in a specific way; how with the aid of specific haemodynamic forces and haemostatic conditions it maintains the specificity of its cells; how with the aid of the central and centrifugal nervous system it is stimulated to function at the right time and with the necessary intensity; what the conditions are for nutrition in general, to maintain function and timing; which conditions impair function, causing short-term or permanent disorders, etc.

All this is not known and has to be considered. Moriz Benedikt then continues:

In science, these questions come up one after the other over long periods of time.

Just the questions come up, therefore!

The literature, on the other hand, considers only what is known at any time, without enquiring into the unknown, and behaves as if the basic problem had already been fully solved.

That is, makes no mention of the unknown. People like Moriz Benedikt are at least able to list all these unknown elements.

This is why only a small part of the theories which prevail at any given time is true, and they contain a colossal percentage of new and inherited errors which will continue on through generations as original sin.

What is this medical man really saying? He says: We have a medical literature but it only deals with the known. Yet the unknown keeps coming up after long intervals of time. What does Benedikt want? He wants people to be aware of what they do not know. What would happen in the case of the liver, for instance? A member of the medical profession taking the opposite view of Benedikt who gave a description of the liver would try to discover the biochemical properties of liver cells and present the fact that the liver secretes bile. He would be satisfied with this, for he does not talk about anything that is not known. Benedikt would say: Alright, the liver secretes bile; this is due to the biochemical constitution of the liver cells. But as a conscientious scientist I must also say everything I do not know about the liver and the bile. He would therefore write in his book:

This we know, but we do not know how the liver comes to be in that particular place; how the statics and dynamics of the blood, or rather the circulation, affect the liver; how the nervous system relates to the liver, both the system as a whole and the individual nerves; and how the liver contributes to nutrition. Benedikt’s books would therefore be different from those of other authors. As a scientist he would in this respect be extremely modest.

But he says this question as to the unknown comes up in the course of centuries; yet because of the way the questions are put, if we go down to fundamentals, then even taking Benedikt’s point of view, we could go on till Judgement Day, always putting down what is known and then what is unknown and the many questions that arise. Benedikt’s books would only differ from those of other authors in that they also list what is not known. Yet he would never accept that something we do not know has to be taken out into the cosmos, that it will continue to be unknown until we explain it out of the cosmos.

You see, a rational medical practitioner here says, speaking in the terms of his discipline, that we cannot explain the human being with the means at our disposal; all we can do is to list the things we do not know. Unfortunately he persists in his refusal to consider something which does provide answers to these questions, questions he says concern the unknown, and of course the answers can only be provided slowly and gradually.

Thus the questions are there in ordinary science. Anthroposophy offers the answers to these questions. This is the truth. It is something we should stress over and over again, quite emphatically.

Moriz Benedikt believes that the bad habits to be found in his particular science are due to the fact that people know nothing of the unknown, offering to humanity what they know on the basis of facts established in the sense-perceptible world only. He gets quite sarcastic as he goes on to say: This scientific ineptitude flourishes today ... not his ineptitude, but that of his colleagues! as much as it did a thousand years ago; indeed it is worse than ever, since production has become so much faster.

He means to say that in earlier times it was not possible to publish one’s misdemeanours so quickly.

Every short-lived notion or undertaking is published so quickly nowadays that medical journalism only needs a “Hot Wire column”, and perhaps we may see the day when telephone booths are set up just to make sure that scientific “ideas" do not lie fallow even for nine minutes.

Publication took more years in the past than it takes hours today.

Oh, and Moriz Benedikt also knows what he thinks of the public, who listen to the medical profession and swear by them! He puts it simply in the following rhyme:

Miller, Brown, Smith and Read join in every heinous deed.

He then starts to reproach his colleagues again—the heinous deeds are theirs, of course—saying:

These unsatisfactory conditions in biology will not improve until a major reform in education starts with the teachers. Anyone unable to show that he has made a serious study of mathematics and mechanics is not fit to be a thinker or a scientist, let alone a teacher. Individual genius has always achieved much; it limps, however, and will go on limping until it has learned to walk first in the school of mathematics.

Not everyone who wants to listen to something sensible will need mathematics, of course. But to work with genuine science one does need to be trained in mathematical thinking. This is why Plato—Moriz Benedikt is very rude about him, by the way—wrote on the doors to his academy: Admittance only for those trained in mathematics. This does not prevent present-day philosophers, who have not been trained in mathematics, to write about Plato, of course. And we may truly say: Most of the people who write about Plato today would not have gained admittance to his academy if it still existed. You will see, from what I have read to you from Moriz Benedikt’s booklet, how modern scientific minds view something they themselves really ought to desire, and how someone who, whilst not an anthroposophist but a rather vain individual who has got into some conflict with his colleagues, has nevertheless had some faint notion of the harm that is done—how such a person judges the situation. Let us be very clear about this: The situation we have today is exactly as an unbiased observer with insight gained in anthroposophy is compelled to describe it. The proofs are to be found everywhere in the world of modern exoteric science, you must merely want to look for them.

What we must do, however, is to learn how to consider the human being in a way which physicists would consider perfectly sensible. I have already given you the analogy: If you study a compass needle and insist on saying it assumes a particular direction out of its own inherent powers, you will never understand why there are north-and south-pointing forces in the compass needle. We must understand that the whole earth has two forces, that the poles of the two forces are determined from outside. In the same way it is utterly wrong to put a human being on the dissecting table and decide to explain the whole of the human being’s nature on the basis of what lies inside the skin. We need the whole world to understand the outer and inner aspects of the human being.